Has Employment of Cardiologists Been a Successful Strategy? – Part 3

Click for Part 1 and Part 2 of this article.

Let's assess whether the employment of cardiologists has been good for hospitals and health systems.

Given the magnitude of purchases of cardiology practices by hospitals and health systems, there is obviously some perceived benefit from cardiologist employment; otherwise, these organizations would not expend the time, money and emotional energy involved in the negotiations that can sometimes take up to two years to complete.

In fact, it was reported in a study by Avalere that hospitals acquired 5,000 physician practices in a single year from July 2015 to July 2016, representing a 100 percent increase in hospital-owned physician practices since 2012-2016.

In 2018, the American Medical Association reported that, for the first time, employed physicians now exceed private practice physicians. One can reasonably conclude that hospitals have a large appetite for acquiring physician practices.

Reducing costs, improving care quality, increasing efficiency, and implementing value-based care are among the top reasons why hospitals and health systems are looking to mergers and acquisitions of both physician practices and other hospitals. Usually, the stated intent is that acquiring or merging with another provider organization allows both providers to leverage economies of scale, brand recognition and other valuable capabilities.

Additional reasons why hospitals and health system may acquire physician practices include:

- The opportunity to grab business from their competitors by acquiring physicians who hospitalized their patients at competing facilities.

- Position the organization's accountable care organizations for capitated or "value-based" reimbursement.

- Hospitals and health systems tire of negotiating with local independent groups over coverage of the ER, ICU, and diagnostic services such as radiology and pathology.

- It is much easier to enforce referral and utilization policies on physicians who are employees rather than simply independent businesses who happen to support a hospital at a given moment in time.

Interestingly, as many hospitals and health systems acquired physician practices and built large multi-specialty medical groups, they often cite the large amounts of financial losses they are incurring, with operating loss per physician averaging close to $150,000 annually. So why would organizations, despite the alleged strategic intent, enter into such a negative financial arrangement as employing physicians? There are two reasons.

First, employing cardiologists locks up a very lucrative source of revenue. A 2019 Physician Inpatient/Outpatient Revenue Survey showed that noninvasive cardiologists generated an average of $2.3 million of net annual revenue per year for hospitals while invasive cardiology generated $3.5 million per year. The same survey showed $2.7 million and $2.5 million, respectively, in 2004.

Second, hospitals report losing money on their employed physicians because physicians' compensation, plus practice expenses and corporate overhead, significantly exceed the professional collections of the practices. I believe that these direct losses are, to a degree, a byproduct of selective accounting practices because hospitals frequently do not attribute any of the "downstream" or associated revenue to employed physician practice income.

It appears that hospitals and health systems must feel that there are tremendous benefits to employing physicians, especially cardiologists, since it has become such a commonplace occurrence. A change of this magnitude would not occur if some, or if not all, of the previously mentioned benefits were not being attained.

However, a Google search finds the internet full of articles focused on advising hospitals and health systems on how to have a successful physician enterprise strategy, suggesting that employment of physicians is not a walk in the park.

Let's move on to whether the employment of cardiologists has been good for the cardiologists themselves. Since any practice acquisition must involve a willing buyer and seller, one must assume that the many cardiologists who changed from private practice to employed did so willingly, and choose to remain that way, right? The answer to that gets interesting.

Generalizing about the pros and cons of employed physician practices – or any practice type – is difficult because of the variety of reasons why physicians do or do not embrace employment vs. private practice.

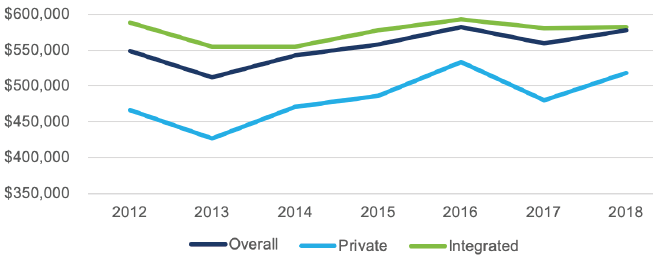

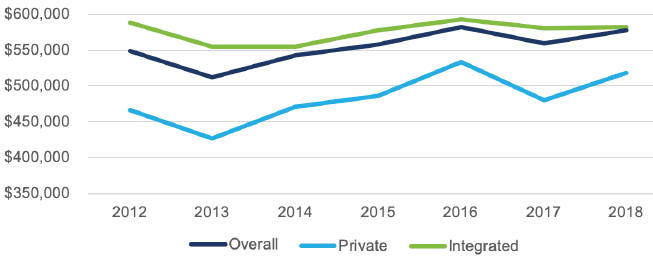

One thing that is certain is on average, employed cardiologists get paid higher than private practice cardiologists. The graph below illustrates that this fact has been true for a number of years, although the gap is narrowing.

Many employed cardiologists chose to become employed because, among other things, they wanted to stabilize their incomes and lessen their risk in an increasingly uncertain environment. However, as I have spoken to many cardiologists around the country at national meetings and in my previous role as a heart program consultant, they are not naïve.

They acknowledge they have traded autonomy for perceived better security and, in most cases, they are cognizant that their income is being protected or subsidized through employment. On the other hand, independent cardiologists say they are happy that they can run their own show and do not have to play politics or follow hospital policies they disagree with.

However, payment policies from governmental agencies and health insurance companies heavily favor large health systems and make it challenging for independent practices, especially smaller practices, to survive or compete. At the same time, cardiologists have historically been exceptional entrepreneurs, who successfully operated complex practices and enjoy having some degree of autonomy.

It is becoming apparent that many cardiologists, like most all other physicians, are growing more jaded about the medical profession. Reports such as "one in four cardiologists is burned out" and "just 27 percent of cardiologists are happy at work" reflect this idea.

Can that be attributed to employment? Studies suggesting that hospital-employed physicians are less satisfied and that independent physicians are happier are becoming a more common theme.

A third study, this time conducted by Medscape, surveyed almost 5,000 physicians to find out whether they feel that they would be better off as an employee or as a partner or solo practitioner. The report, "Who's Happier – Employed or Self-Employed Doctors" found that more self-employed physicians than employed physicians are satisfied with their work.

Is employment turning out to be a success for many cardiologists? Some common themes I have heard from cardiologists include:

- The idea that "you can just practice medicine" in an employed situation, while sometimes implied at the time of a practice acquisition, often turns out to be a false statement. Many cardiologists lament that they are eventually treated as a basic employee and inevitably will be directed to do something you strongly disagree with or had no input in to.

- The idea that "physician employment creates alignment" is a myth. Hospitals and physicians often struggle to find common ground in what some people describe as a "profit vs. patients" conflict.

- Independent physician practices and hospitals and health systems usually have dramatically different cultures. As in any industry, merging cultures often is the key aspect to whether a merger or acquisition is successful.

- The heavy emphasis on economic vehicles such as compensation models and incentive metrics used to promote alignment (vs. a focus on relationships) turns employment into transactional negotiations vs. effective partnerships.

- The traditional role of the physician as controller of the delivery of health care services has been increasingly superseded by an expanding array of corporations, integrated delivery networks and large medical groups, often which place physicians in corporate-style structures that no longer value individual physician input or preserve specialty-specific governance.

- The role of the hospital as the center of the health care delivery system is changing. While inpatient activity still gets much attention, health care is now much more of an ambulatory industry where patient care is mostly handled outside the walls of the hospital, sometimes in nontraditional settings or ways.

Hospital leaders who maintain a myopic view and fail to see this broader picture struggle with physicians who are no longer as hospital centric as they were in the past.

Many of the cardiologists who left independent practices for employment may be better off economically as an employed physician (in terms of income) but are not as satisfied or professionally fulfilled as their independent counterparts.

This seems to be especially true for those cardiologists who once worked in an independent practice and have recent memories of what that was like vs. employment to draw comparisons from. An attorney who was instrumental in negotiating many of today's cardiology practice employment agreements used to say, "If your income is great, you are happy one day every two weeks, but if your governance and culture are bad, you are unhappy every day."

Drawing a broad conclusion about cardiologist satisfaction with employment is difficult since each circumstance is unique. For example, the might be a 55-year-old employed cardiologist who once was part of a private practice and now must negotiate a more bureaucratic and complex process for initiating program changes or funding purchases within a health system.

This cardiology might have a vastly different perspective and rationale than a 35-year-old employed cardiologist who has worked for a large health system since day one after fellowship vs. a cardiologist in an independent practice, which has relatively equal activity at competing hospitals and is determined to stay independent.

From my own experience as a consultant and cardiology practice administrator, I offer the following observations:

- Successful and effective alignment between cardiologists and hospitals is hard and therefore, elusive in many employed scenarios.

- Many employment situations started with the best of intentions, but those intentions often did not receive the necessary ongoing attention to make them a reality.

- High rates of turnover among the administrative leadership involved in cardiologist alignment often results in a TCG Deficiency (or lack of trust, consensus and grit) that impedes progress in capturing the potential synergies and benefits of being part of a hospital/health system.

Whether you agree or disagree with whether the employment of cardiologists has been a successful strategy, the reality is that, at best, it has been successful in some places but is not likely viewed that way in many communities. f that is your situation, what are realistic steps to take?

I tried to tackle that question in a blog post in 2017: Results are in – the key attributes of hospital physician alignment.

That research, and the various group discussions that were associated with it, confirmed that there are some attributes that are consistent with successful alignment such as trust, consistency of relationships, shared inter-dependent vision, etc. My experience has shown that if you conduct a post-mortem on any failed cardiology employment strategy, you will most likely find the absence of these three components (among other things).

If you are looking for something like a roadmap on how to get to stronger alignment, one place to start might be the 2015 whitepaper from the American Hospital Association and American Medical Association, Integrated Leadership for Hospitals and Health Systems: Principles for Success. This offers some specific tactical approaches for how hospitals and physicians can bridge their differences in culture, values and expectations.

Another place to start might be developing a compact between the health system and physicians.

Despite everything, there is one issue as deeply rooted somewhere at the heart of any struggling or failed employment arrangements: the impositions of health system decisions and programs inflicting deep lasting wounds with physicians. A July 26, 2018 STAT article eloquently captured the concept: Physicians Aren't Burning Out, They Are Suffering From Moral Injury.

Maybe moral injury is just an unfortunate byproduct of lack of trust, or maybe moral injury produces lack of trust. I think it needs to be recognized as a critical attribute of alignment all on its own. Let me offer a common example: compensation.

We all know that any alignment vehicle ultimately has some aspect of compensation involved, either as the entire compensation plan (employment and most PSAs) or incentives (co-management) or both. Where I see moral injury often being inflicted is the common philosophy by health systems that physician compensation must be linked to productivity.

In a 2018 MedAxiom webinar, Pooled Compensation, MedAxiom's Joel Sauer shared that 64 percent of employed cardiology practices are in a 100 percent productivity (assumedly wRVU) compensation model, whereas only 4 percent of private cardiology groups are.

What does this have to do with moral injury? Quite a bit. There can be a common belief among health systems that "physicians won't work hard unless they are paid on production." I have heard that many times, even from health system physician CEOs. This prevailing attitude is one of the ways that moral injury is inflicted on physicians by challenging their belief systems – it disrespects their decision-making, insinuates money (volume) is more important than quality and disengages them from the greater good.

This conclusion is echoed by author Daniel Pink in his bestselling 2009 Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, where he concludes that higher pay and bonuses resulted in better performance only if the task consisted of basic, mechanical skills. It worked for problems with a defined set of steps and a single answer. If the task involved cognitive skills, decision-making, creativity or higher-order thinking, higher pay resulted in lower performance.

Think about it – what other health industry professional's pay do we feel we need to link to volume? Do pharmacists get paid by the dose? Do nurses get paid for each visit to a patient room? Do physical therapists get paid for each treatment rendered? Do executives get paid for each decision made? You get the point.

I am not suggesting that 100 percent salary for physicians is the answer. However, I am suggesting is that alignment with physicians will continue to suffer as long as we keep perpetuating an environment that inflicts moral injury from poorly designed compensation plans; insistence that all specialties must be treated exactly the same in a medical group; by taking away individual practice governance; by not respecting and promoting physician leadership and involvement in decision; and by not being transparent with data.

Want to do a postmortem to resurrect your alignment? You might start by reflecting long and hard on where you are inflicting moral injury. Better yet, ask the physicians. But do not be surprised if they do not trust you enough to think there is some hidden motive behind the question and are reluctant to be honest.

Every community and organization where employment of cardiologists exists will have their own unique story regarding whether the "marriage" between the health organization and physicians has been successful from a patient, organization and physician perspective. While there are degrees of success for each group, there is not overwhelming evidence of widespread success as a whole.

Maybe that success is yet to come, or maybe it will continue to be elusive and more practices will begin to reverse the trend and join a small but growing trend of cardiologists choosing to transition from employment back to independence.

Disclaimer: The views or opinions presented in this document are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent those of the American College of Cardiology Foundation. The American College of Cardiology Foundation does not in any manner endorse, or guarantee the accuracy of any information included in, any documents created by a third party and linked to in this document. This document is provided for informational purposes only and does not provide legal advice; please consult with your own counsel for legal guidance on compliance with applicable laws and regulations. This document is not intended to and does not encourage any coordination between competitors with respect to employment or compensation practices. To comply with the antitrust laws, competitors should not discuss or agree on salaries or other compensation.