Is It Just a Murmur? | Part 3

Click to access: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

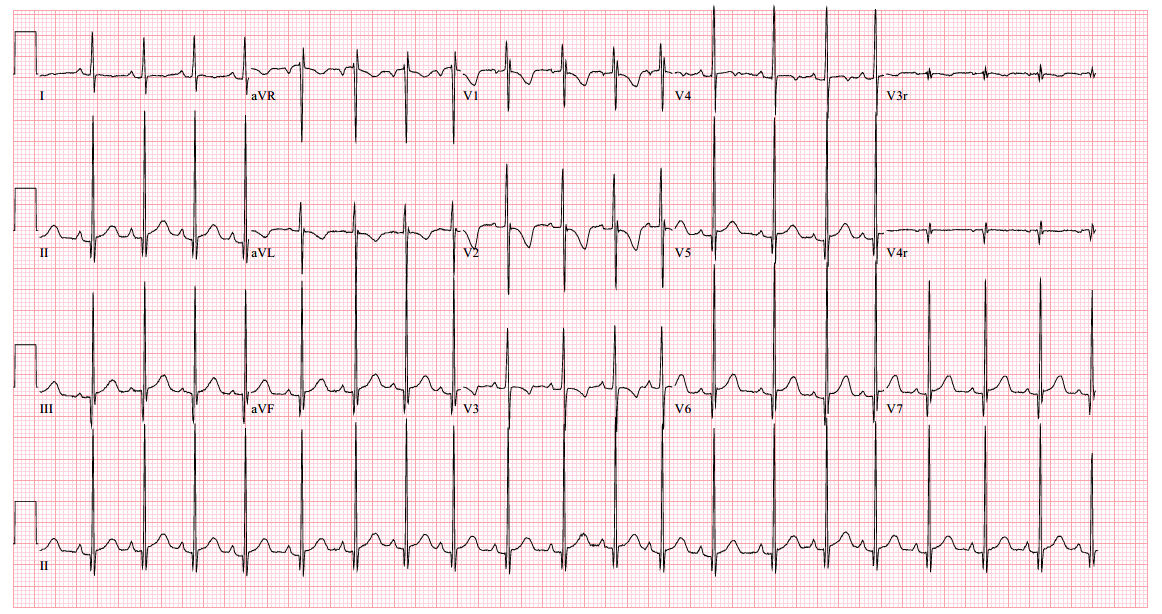

A previously heathy 9-month-old infant was referred to the Pediatric Cardiology Clinic for a newly recognized heart murmur. On physical exam, she was a well-nourished, happy looking, playful child with normal growth and developmental milestones. A grade 2/6 continuous murmur was auscultated along the right sternal border which radiated to the entire precordium but not posteriorly. The murmur persisted despite neck motion and positional changes. There were no other pertinent physical examination findings. Her electrocardiogram is shown.

Figure 1

An echocardiogram clip is shown (Video 1).

Video 1

The angiogram is shown (Video 2).

Video 2

What is the most appropriate next step in the management of the patient?

Show Answer

The correct answer is: B. Refer for Surgical repair of the abnormality.

The echocardiogram clip shows a markedly dilated left coronary artery, and anomalous origin of the right coronary artery from the main pulmonary artery. This is confirmed by a selective left coronary angiography, which shows a severely dilated left coronary artery (LCA) system with late opacification of the right coronary artery (RCA). The RCA is dilated and is perfused by collateral connections from the left anterior descending coronary artery. The RCA does not originate from the aortic root and drains anomalously into the main pulmonary artery, which creates a left-to-right shunt. Hemodynamic abnormalities, including increased pulmonary blood flow (Qp:Qs ratio of 1.2:1) and elevated left ventricular diastolic pressure (19 mmHg) were noted.

This is a case of anomalous right coronary artery origin from the pulmonary artery (ARCAPA). Blood flow in the collateral vessels between the left and right coronary arteries results in a continuous murmur. Surgical reimplantation of the anomalous right coronary artery is recommended.

DISCUSSION:

Anomalous right coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ARCAPA) is a rare congenital anomaly first described in 1885,1 with an incidence estimated to be 0.02% of the population. It is likely underdiagnosed due to its initially relatively innocuous nature compared to anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA). About a third of patients have other associated congenital heart malformations such as aortopulmonary window, tetralogy of Fallot, atrial and/or ventricular septal defect, double-outlet right ventricle, pulmonary stenosis, aortic stenosis, and coarctation of the aorta.2

Patients with ARCAPA may present with myocardial ischemia as their pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) decreases due to a "steal phenomenon". Blood flow from the left coronary artery perfuses the collateral vessels, and drains into the right coronary artery, which in turn drains into the pulmonary artery as PVR decreases. Patients with massive collaterals, such as in this case, may have a significant left to right shunt and left heart volume overload.3 In some patients, an ostial web or stenosis of the RCA are protective against the "steal phenomenon".2,3

Young infants are rarely symptomatic. The lower RV wall thickness in most pediatric patients with ARCAPA results in a lower oxygen demand that makes symptoms due to ischemia less likely.4-6 An asymptotic murmur is the presenting finding in ~ 50% of young infants. Patients can also present with angina, congestive heart failure, dyspnea, palpitations, myocardial infarction, myocarditis, bradycardia and sudden cardiac death. Perioperative mortality and death due to congestive heart failure have been reported.2

The electrocardiogram is normal in 29%. Abnormal electrocardiographic findings include left ventricular hypertrophy (29%), right ventricular hypertrophy (10%), biventricular hypertrophy (6%), ST segment or T wave changes (8%), Q waves in the inferior leads (6%), ischemic changes (4%), incomplete right bundle branch block (6%), left bundle branch block (4%), atrial arrhythmia (6%), and right axis deviation (6%). Chest radiographs are normal in 40%, while some have cardiomegaly or pulmonary edema. Patients old enough to have an exercise stress test may have ischemic changes or wall motion abnormalities.2

With meticulous imaging of the origins of coronary arteries, the diagnosis can be made by transthoracic echocardiography, which may show dilation of the left main coronary artery and its branches, with retrograde flow in the proximal right coronary artery. Collateralization from the left to the right coronary artery can be readily seen as prominent flow in the septal perforators, which can mimic multiple muscular ventricular septal defects. In the setting of significant collateral communication which leads to a significant left to right shunt, the left atrium and left ventricle can become dilated.3

Surgical intervention consists of reimplantation of the RCA, including excising the anomalous origin of the RCA along with a button of the pulmonary arterial wall and translocating it into the anterior aspect of the ascending aorta.2,4

On pathologic examination or surgical inspection, the anomalous coronary artery is dilated, thin-walled, or vein-like, and may arise from the anterior main pulmonary artery, or the right posterior or anterior pulmonary sinuses.1,2

In summary, patients with ARCAPA may mirror the symptoms of ALCAPA, albeit with a later presentation beyond infancy. Most children are referred for an asymptomatic murmur. Some patients present with significant symptoms of myocardial ischemia including sudden cardiac death and congestive heart failure. Electrocardiographic findings are often non-specific. The diagnosis can be made with careful transthoracic echocardiography that includes meticulous attention to the origins of the coronary arteries.3,5 Computed tomography angiography of the coronary arteries is also diagnostic. Alternatively, cardiac catheterization provides hemodynamic assessment in addition to coronary angiography to confirm the diagnosis. Surgical reimplantation of the anomalous RCA is recommended.

References

- Brooks HS. Two cases of an abnormal coronary artery of the heart arising from the pulmonary artery: with some remarks upon the effect of this anomaly in producing cirsoid dilatation of the vessels. J Anat Physiol 1885;20:26–9.

- Williams IA, Gersony WM, Hellenbrand WE. Anomalous right coronary artery arising from the pulmonary artery: a report of 7 cases and a review of the literature. Am Heart J 2006;152:1004.e9-1004.e17.

- Herlong JŔ, Barker PCA. "Chapter 30. Congenital Anomalies of the Coronary Arteries". In: Lai WW, Mertens LL, Cohen MS, Geva T, eds. Echocardiography in Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease. Wiley-Blackwell; 2016: 584–608.

- Kouchoukos NT, Blackstone EH, Hanley FL, Kirklin JK, eds. "Chapter 46. Congenital Anomalies of the Coronary Arteries". In: Kirklin/Barratt-Boyes Cardiac Surgery. Morphology, Diagnostic Criteria, Natural History, Techniques, Results, and Indications. Philadelphia: Elsevier Ltd; 2013:1643–71.

- Lopez L, Colan SD, Frommelt PC, et al. Recommendations for quantification methods during the performance of a pediatric echocardiogram: a report from the Pediatric Measurements Writing Group of the American Society of Echocardiography Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease Council. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:465–95.

Click to access: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3