Feature | Cardiac Amyloidosis and How to Stop Missing the Diagnosis

Cardiac amyloidosis used to be considered an ultra-rare disease with no treatment options. No longer. Advances in noninvasive testing have led to greater awareness, earlier diagnosis and improved outcomes for patients. Concurrently, important advancements in the treatment of ATTR amyloidosis have significantly changed the landscape of care for those affected by the disease.

But these important gains come with a caveat. The disease is underdiagnosed. If clinicians don't detect and diagnose the disease early, patients will continue to suffer, except now that suffering may be needless.

"Every provider has probably seen patients with cardiac amyloidosis in their office several times over the years and never recognized it. Now that we have a noninvasive means of diagnosing it and a disease-specific treatment that works, it's time to stop missing the diagnosis," suggests Mathew S. Maurer, MD, FACC, at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City.

Cardiac Amyloidosis 101

Cardiac amyloidosis is an infiltrative heart disease wherein misfolding proteins aggregate amyloid fibrils deposited in the interstitial space between cardiac myocytes. While as many as 40 proteins are known to form insoluble amyloid fibrils, the vast majority of cardiac amyloidosis is caused by just two: light-chain amyloid (AL) and transthyretin amyloid (ATTR).1

AL amyloidosis is a rare disease with a rapidly progressive clinical course in part due to the toxic nature of light chains. The disease arises from overproduction and misfolding of monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains. Left untreated, AL amyloidosis has a median survival of less than six months in patients with cardiac involvement.

ATTR-cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) is the form of cardiac amyloidosis currently getting the most attention. There are two subtypes: hereditary or variant ATTR (ATTRv) is caused by TTR mutations (of which there are about >130), while wild-type ATTR amyloidosis (ATTRwt), the most common form of cardiac amyloidosis, occurs without a pathogenic mutation and is a result of as yet undefined age-related changes.

– Mathew S. Maurer, MD, FACC

"Ten or 15 years ago, amyloidosis was thought to be an ultra-rare disease and providers were nihilistic because there weren't any treatments. So, not only was it hard to diagnose and protean," says Maurer, there was little impetus to diagnose it because there was no treatment.

"Now, we're not even sure it's still a rare disease, using the accepted definition of a disease affecting <200,000 folks in the U.S. It's certainly much more common than we thought."

This change is a result of two concurrent advances in the field. The first is the advent of a nonbiopsy method using technetium-labeled bone scintigraphy to diagnose the condition in patients for whom lab tests have ruled out the substrate for AL.2 Previously, definitive diagnosis of amyloidosis required an endomyocardial tissue biopsy, but now biopsy is required in a minority of affected patients.

"Once we realized we could use noninvasive testing, we learned important things, like that up to 13% of patients hospitalized with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction [HFpEF] who have a thick-walled heart have amyloidosis,"3 says Maurer.

Indeed, several epidemiological studies now indicate that cardiac amyloidosis is far more common than previously thought. For example, as many as one in seven to eight patients referred for TAVR show cardiac amyloid infiltration on bone scintigraphy.4-6

"We think it's likely that maybe 1% of people over the age of 75 without a clinical syndrome just walking on the street may have cardiac amyloid because it's an age-dependent phenomenon," says Maurer. There is also a male preponderance for reasons that are unclear.

Epidemiological studies have also revealed that certain disease variants almost exclusively affect certain populations, such as Black and Caribbean Hispanics who have West African ancestry. One common variant encountered in the U.S., the Val122Ile variant, is present in 3.4% of individuals (1 in 29) who self-identify as Black. Given its prevalence, there are about 1.5 million allele carriers of the Val122Ile variant in the U.S., although its penetrance is incomplete.

Diagnosis of Cardiac Amyloidosis: Blood Tests + Scan

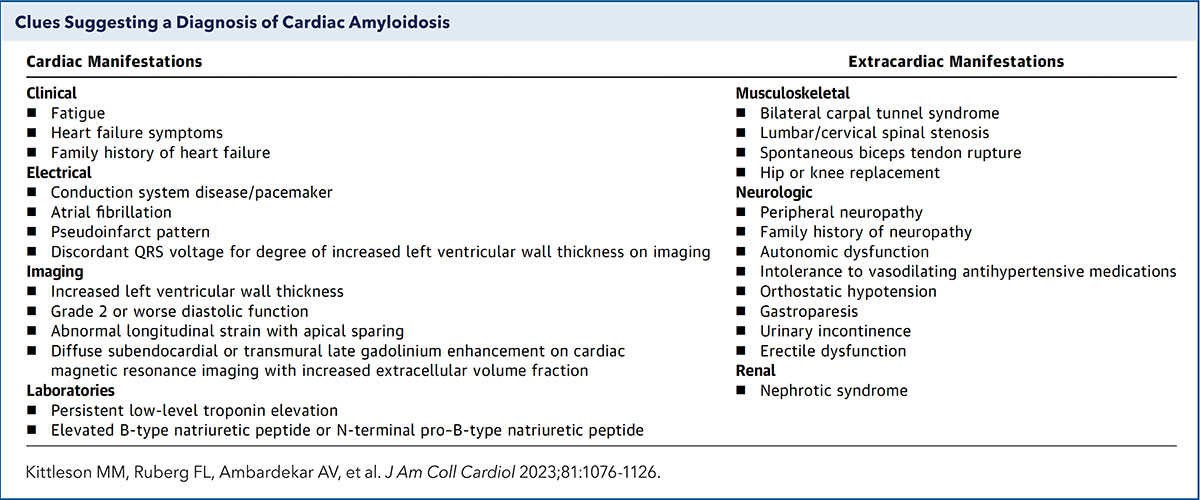

"The diagnosis of amyloidosis can be challenging, but it's not as hard as people think. I believe any cardiologist should be able to diagnose and treat cardiac amyloidosis," says Michelle Kittleson, MD, PhD, FACC, at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. What's the trick? Be mindful of the red flags (Table).

"Maybe they don't quite look like the typical HFpEF patient. Or maybe they have a family history of a cardiomyopathy or neuropathy. Or perhaps they have some neuropathy themselves or some musculoskeletal findings, like carpal tunnel or spinal stenosis. These are the clues that should lead you to look for amyloidosis," says Kittleson.

"When a patient presents with shortness of breath, leg swelling and a normal ejection fraction, don't just diagnose HFpEF or write it off as not related to the heart. Look a bit further, she adds."

In keeping with the ACC's Strategic Goal of generating actionable knowledge, the College published an Expert Consensus Decision Pathway (ECDP) on cardiac amyloidosis in March 2023.7 "With this ECDP, we hope to show clinicians, and not just cardiologists, how seemingly disparate findings can coalesce into a satisfying, unifying diagnosis," says Kittleson, who chaired the writing committee.

Supporting Practice

Click here to access ACC's free online course, Cardiac Amyloidosis: Accelerating Diagnosis and Treatment, to learn more.

Click here for patient-centered information on cardiac amyloidosis to facilitate shared decision-making conversations.

Stay on top of the latest science with JACC: CardioOncology at JACC.org.

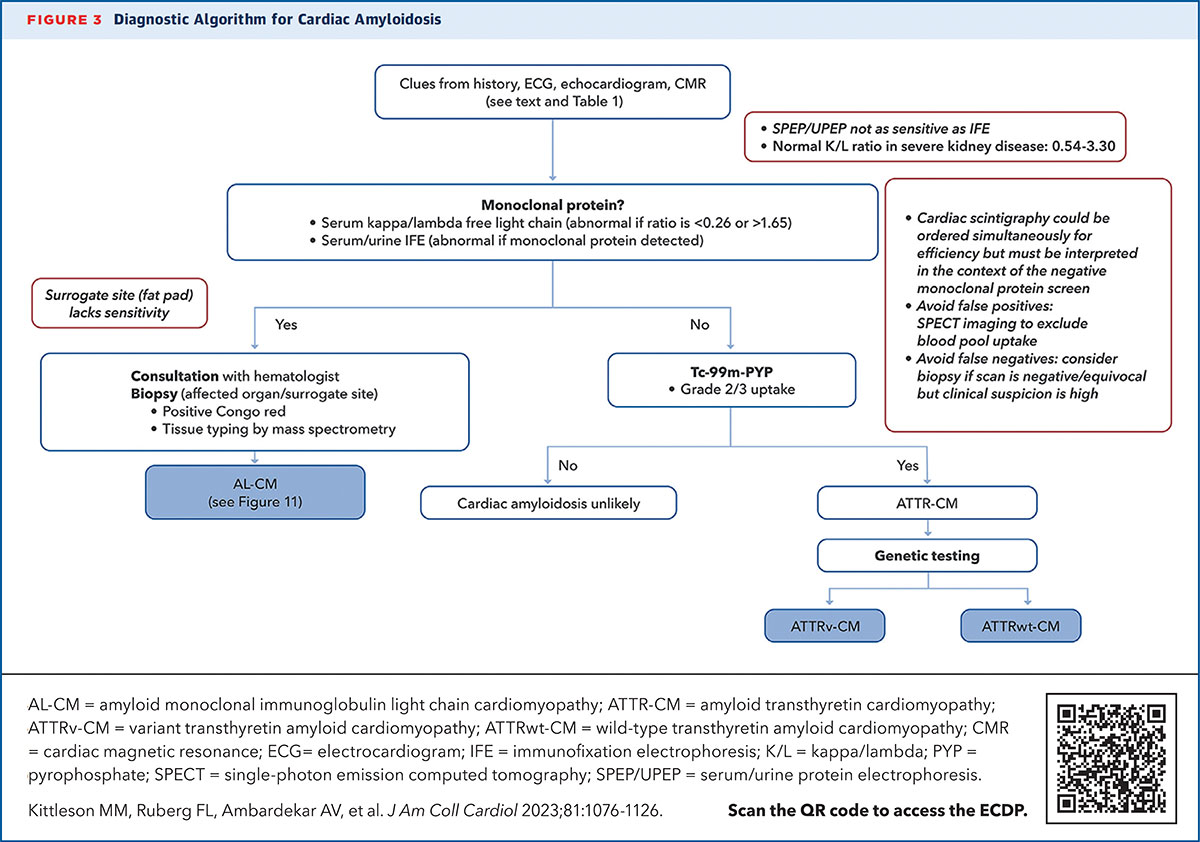

Once there is clinical suspicion for cardiac amyloidosis and a decision to screen has been made, it's essentially a two-step process to a noninvasive diagnosis of ATTR-CM: a monoclonal protein screen and a nuclear scan (Figure).

The serum free light chain assessment and the serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation (not just a serum/urine protein electrophoresis) combined have a 99% sensitivity for identifying someone at risk for AL amyloidosis.8

If the lab tests are normal, the next step is imaging to evaluate for ATTR amyloidosis. Once AL is ruled out, the specificity of PYP bone scintigraphy for ATTR-CM approaches 100%.

"If there's no significant uptake, cardiac amyloidosis is unlikely. If there is, look further," says Kittleson. In most cases, endomyocardial biopsy is only needed if a monoclonal protein is detected, or if imaging results are equivocal. Once a diagnosis of ATTR-CM is made, genetic testing can differentiate between the hereditary and wild-type forms of the disease.

The ECDP also reviews therapy for cardiac amyloidosis and emphasizes the importance of multidisciplinary care, offering helpful guidance on the different manifestation of the disease and when patients should be referred to another specialist.

What clinicians most need to realize, stresses Maurer, is that patients need to be diagnosed and started on therapy in a timely fashion. "Tafamidis makes people live longer. We're no longer in a situation of diagnosing people with something for which we have no treatment," he says. "Importantly, what a patient loses, they don't regain. When their functional capacity declines, things will stabilize after starting treatment with tafamidis, but they never get back to where they were a year earlier on average."

Treatment: Timely Patient Care

Therapy for ATTR-CM focuses on tafamidis and the management of heart failure or arrhythmias. Tafamidis is currently the only disease-modifying therapy available that is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). It is an orally active drug that binds to the thyroxine site of TTR, stabilizing it, and inhibiting or slowing the formation of amyloid fibrils.

"Tafamidis prevents the protein, which looks like a four-leaf clover and is produced predominantly in the liver, from falling apart, which happens with aging or in the presence of a mutation. The pieces are what line up and form the amyloid fibrils. Tafamidis fits in between the leaves of the protein and stabilizes it, preventing or slowing disease progression," offers Maurer.

Tafamidis was FDA approved in May 2019 for the treatment of ATTR-CM based on the findings of the ATTR-ACT trial, which evaluated the safety and efficacy of tafamidis in 441 patients with hereditary or wild-type ATTR and HF.

After 30 months, tafamidis reduced all-cause mortality by 30% (29.5% vs. 42.9%; hazard ratio, 0.70; p=0.026) and cardiovascular hospitalization by 32% (p<0.0001). Significant improvements were seen in secondary endpoints related to quality of life and exercise tolerance.

– Michelle Kittleson, MD, PhD, FACC

Another approach targeting the amyloid cascade are TTR silencing agents. Patisiran (Alnylam Pharmaceuticals) knocks down hepatic production of TTR by about 85% and is approved to treat the hereditary form of ATTR-polyneuropathy. In October 2023, the FDA declined to approve an expanded indication for the drug despite positive trial findings in ATTR-CM.9

Alnylam has a next generation drug in development called vutrisiran that is more effective and easier to administer. It is already approved for patients with ATTRv amyloid polyneuropathy with or without cardiomyopathy. Topline results from a phase 3 trial of vutrisiran (HELIOS-B) are expected soon. Another RNA-based therapy that targets the production of abnormal TTR protein is eplenotersen, which is currently being tested for ATTR-CM in the CardioTTRansform trial and was recently approved for ATTRv amyloid polyneuropathy, as well.

Economic Barriers and Burdens

"Tafamidis is an extremely well-designed molecule, which stabilizes TTR and is incredibly well tolerated," says Maurer. "The problem is the cost. Tafamidis is currently priced at around a quarter of a million dollars per year, making it difficult to access for many patients."

A recent cost-effectiveness analysis for tafamidis suggested a high incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $880,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained.10 At the generally accepted threshold of $100,000 per QALY used in the U.S., over a 90% price reduction would be necessary to make tafamidis cost effective.

A second TTR stabilizer, acoramidis, has been shown effective in its phase 3 trial and is poised to be approved soon. Any affect on cost remains to be seen.

There is currently, Maurer adds, no head-to-head data to inform whether acoramidis will perform better than tafamidis from a clinical perspective. There were important differences between the phase 3 trials for the two drugs that preclude direct comparison. What is known is that the high cost of these drugs "barring government intervention" will remain a significant barrier to access, he notes.

Despite these challenges, patients with cardiac amyloidosis are doing better, new drugs are being developed and tested, and there is ongoing research into prevention strategies and the identification of early biomarkers. It's an exciting time, says Maurer.

Amyloid Removal: The Holy Grail

Keeping in mind that current treatments only serve to inhibit production of amyloid, drugs that promote fibrin degradation and reabsorption would represent an important advance.

"Amyloid removal would be the Holy Grail for this disease," says Kittleson. She is particularly excited about NI006, a recombinant human anti-ATTR antibody that was developed for the removal of ATTR by phagocytic immune cells. "If there are no concerning safety signals, this will be a game changer down the line," says Kittleson.

In a phase one trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine last spring, treatment with NI006 reduced cardiac tracer uptake on scintigraphy and extracellular volume on cardiac MRI, both of which are surrogate markers of cardiac amyloid load. The drug was well tolerated.

A study involving a single infusion of NTLA-2001, a novel gene-editing therapy, demonstrated a reduction in TTR protein levels in the bloodstream that were sustained after 12 months, suggesting a potential new direction in the treatment of ATTR amyloidosis.

So far, the clinical evidence proving that removing deposited amyloid fibrils will improve organ function is limited to three case reports from the National Amyloidosis Center in London and whether these agents will improve or extend life is unknown.11 An ongoing phase 2 trial of another monoclonal antibody (NN6019-0001) is looking at whether the drug, which has been shown in preclinical studies to bind and neutralize the various prefibrillar species of TTR and prevent the formation of new amyloid fibrils, can reduce the symptoms of cardiomyopathy due to TTR amyloidosis.

Another future treatment option is gene-editing therapy. One candidate, NTLA-2001, has shown promise in reducing TTR protein levels in the bloodstream through targeted knockout of TTR.12 Yet another exciting development is ALN-TTRsc04, an investigational RNAi therapeutic that aims for greater than 90% target gene silencing with once yearly dosing.

This article was authored by Debra L. Beck, MSc.

References

- Benson MD, Buxbaum JN, Eisenberg DS, et al. Amyloid nomenclature 2020: update and recommendations by the International Society of Amyloidosis (ISA) nomenclature committee. Amyloid 2020;27:217-22.

- Gillmore JD, Maurer MS, Falk RH, et al. Nonbiopsy diagnosis of cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Circulation 2016;133:2404-12.

- González-López E, Gallego-Delgado M, Guzzo-Merello G, et al. Wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis as a cause of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 2015;36:2585-94.

- Nitsche C, Scully PR, Patel KP, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of concomitant aortic stenosis and cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:128-39.

- Scully PR, Patel KP, Treibel TA, et al. Prevalence and outcome of dual aortic stenosis and cardiac amyloid pathology in patients referred for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur Heart J 2020;41:2759-67.

- Castaño A, Narotsky DL, Hamid N, et al. Unveiling transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis and its predictors among elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2879-87.

- Kittleson MM, Ruberg FL, Ambardekar AV, et al. 2023 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on comprehensive multidisciplinary care for the patient with cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023;81:1076-1126.

- Witteles Ronald M., Liedtke Michaela. AL amyloidosis for the cardiologist and oncologist. JACC CardioOncol 2019;1:117-30.

- Maurer MS, Kale P, Fontana M, et al. Patisiran treatment in patients with transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 2023;389:1553-65.

- Kazi DS, Bellows BK, Baron SJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of tafamidis therapy for transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2020;141:1214-24.

- Fontana M, Gilbertson J, Verona G, et al. Antibody-associated reversal of ATTR amyloidosis–related cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2023;388:2199-2201.

- Gillmore JD, Gane E, Taubel J, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 in vivo gene editing for transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 2021;385:493-502.

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies

Keywords: Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications, Amyloidosis, Cardiac Amyloidosis, Myocytes, Cardiac, Rare Diseases, Immunoglobulin Light-chain Amyloidosis, Cardiomyopathies