Cardiovascular Imaging in Pregnancy

Quick Takes

- Transthoracic echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging without contrast are first-line modalities for cardiac imaging in the setting of pregnancy.

- Appropriate diagnostic studies should not be delayed or withheld from pregnant patients, even if they require radiation exposure or contrast.

Introduction

The prevalence of cardiovascular disease in pregnant people is estimated to be 1-4%,1 and this is expected to increase. To provide comprehensive care for these patients, clinicians should be comfortable recommending safe and appropriate diagnostic cardiovascular imaging. This care includes shared decision-making with the patient to discuss the risks and benefits of each study.

Physiologic and Anatomical Considerations

During pregnancy, the body undergoes several physiologic changes. Beginning in the first trimester and peaking by the second trimester, plasma volume, heart rate, cardiac output, and stroke volume increase while mean arterial pressure and systemic vascular resistance decrease. By the third trimester, the heart is displaced upward and laterally. Lying supine can compress the inferior vena cava (IVC), leading to decreased cardiac output, hypotension, and tachycardia. These changes must be considered when imaging studies are performed and interpreted. The left lateral decubitus position is preferable as the uterus enlarges to minimize IVC compression.2

Echocardiography

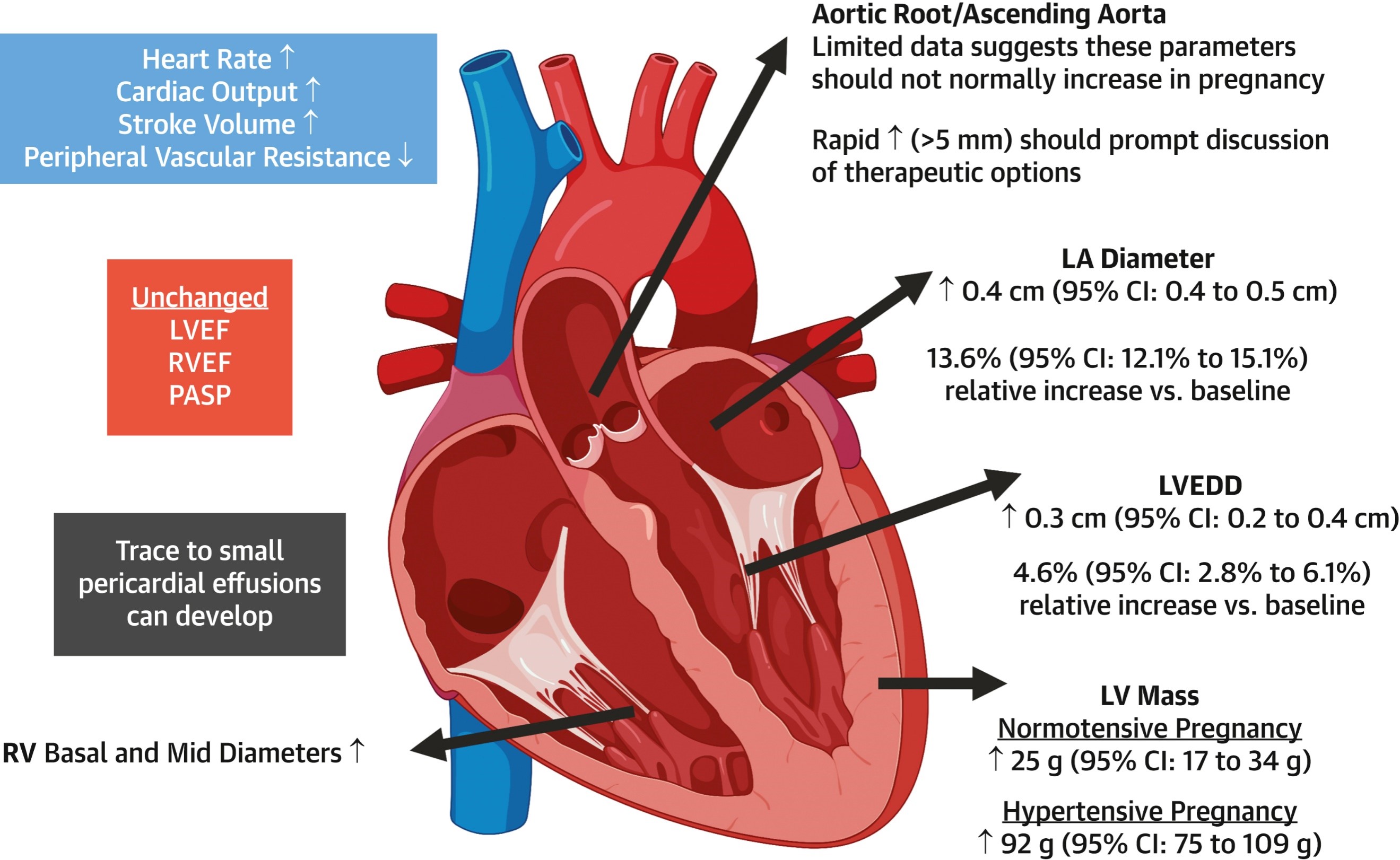

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is a reliable and safe modality of cardiac imaging during pregnancy. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) recommends performing TTE in all pregnant people with pulmonary hypertension, valvular disease, congenital heart disease, aortopathies, or those exposed to cardiotoxic chemotherapeutic agents.3 TTE can be used for serial monitoring of valvular or congenital disorders and to evaluate overall ventricular function and segmental wall motion. Physiologic changes in cardiac structure resulting from pregnancy include increased left atrial diameter, left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic diameter, and a mild increase in LV mass (Figure 1).2 LV and right ventricular ejection fractions and pulmonary artery systolic pressures should not change significantly. The use of agitated saline for evaluation of intracardiac shunting is not recommended in the setting of pregnancy. There are no empirical safety data on the use of ultrasound-enhancing agents (perflutren, sulfur hexafluoride) in pregnancy, although data from animal studies have not shown evidence of harm. Therefore, there should be a risk–benefit discussion prior to using these agents in pregnancy.

Figure 1: Changes to Cardiac Structure and Function in Pregnancy

Expected alterations in commonly measured cardiac dimensions and hemodynamic parameters during pregnancy.

CI = confidence interval; LA = left atrium; LV = left ventricle; LVEDD = left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; PASP = pulmonary arterial systolic pressure; RV = right ventricle; RVEF = right ventricular ejection fraction; ↑ = increase; ↓ = decrease.

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) can be used with the following considerations. Moderate sedation using midazolam should be avoided during the first trimester. After 18 weeks of pregnancy, patients are considered to have a full stomach and are at heightened risk of emesis and aspiration due to relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter and decreased gastric motility. This phenomenon should be considered with both esophageal and endotracheal intubation. If endotracheal intubation is used to perform a TEE, the risk of teratogenesis from anesthetic agents, fetal hypoxia, and miscarriage or preterm birth should be considered. Consultation with an obstetrics or maternal fetal medicine team should be sought for fetal monitoring during procedures after 22-24 weeks of pregnancy.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred over computed tomography (CT) imaging during pregnancy due to the absence of radiation. It can be used without contrast to measure aortic dimensions in pregnancy and can assess wall motion and myocardial function if echocardiographic imaging is nondiagnostic. Gadolinium-based contrast agents are water soluble and cross the placenta, staying in the fetal circulation and amniotic fluid for an indefinite period. Although there is no proven harm to fetuses that have been exposed, its use is still discouraged unless it will alter clinical management.

Radiation Considerations

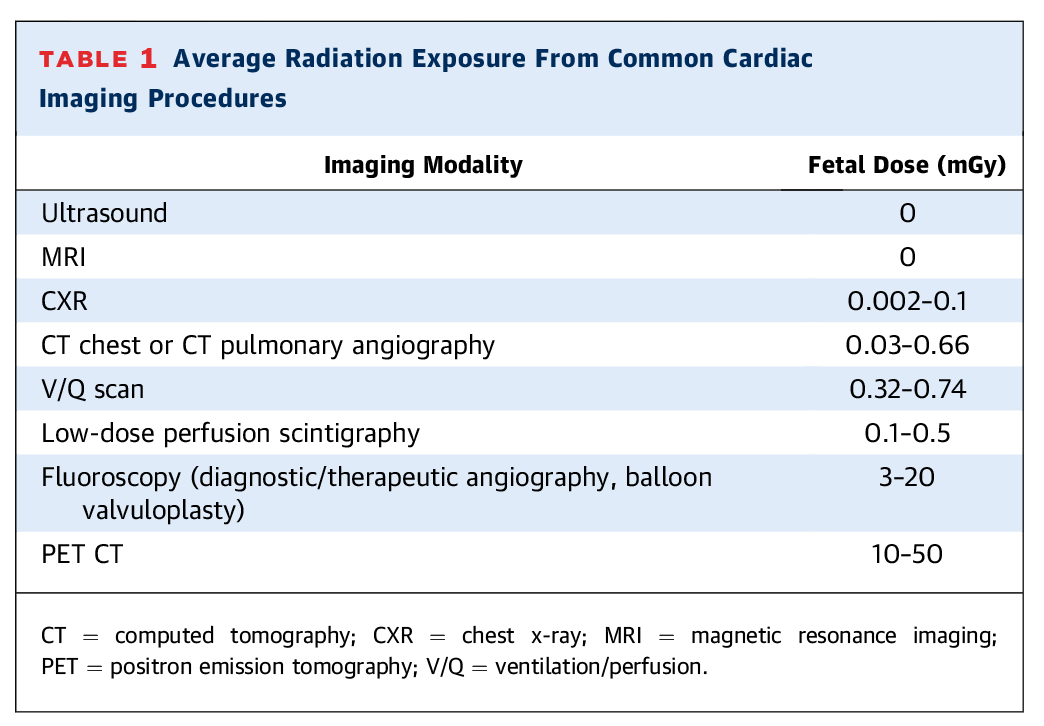

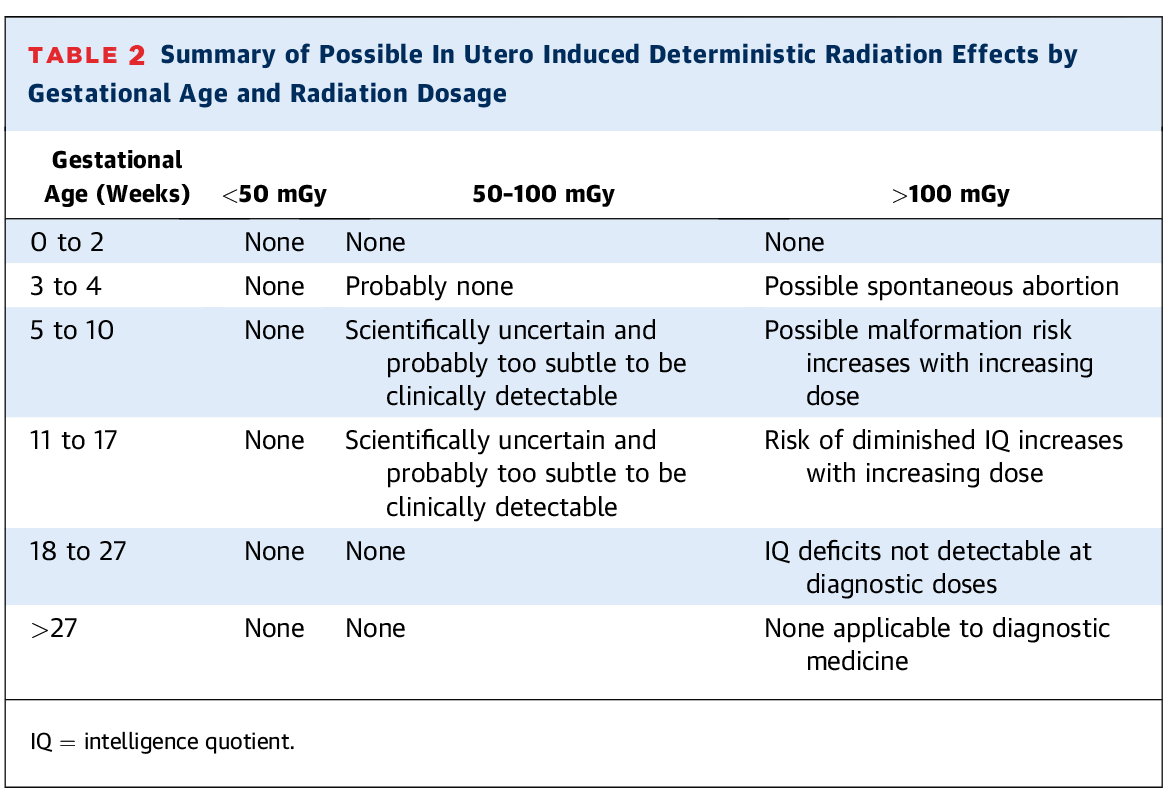

Fetal radiation exposure must be considered if CT, nuclear medicine, cardiac catheterization, or electrophysiologic studies are undertaken during pregnancy. Table 1 outlines the mean exposure from common cardiac examinations.2 As with all radiology studies, imaging during pregnancy follows the as low as reasonably achievable principle while simultaneously aiming to keep the fetus out of the direct beam of radiation. The risk of deterministic effects (i.e., prenatal death, growth restriction) is highest during organogenesis in the first trimester and may occur above 50 mGy3 (Table 2).2 Whereas radiation doses for imaging such as CT have significantly decreased and the risk of deterministic effects are low, stochastic effects (i.e., risk of childhood cancer) are not dose dependent and should be considered.

Table 1: Average Fetal Radiation Exposure From Common Cardiac Imaging Procedures

CT = computed tomography; CXR = chest X-ray; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; PET = positron emission tomography; V/Q = ventilation/perfusion.

Table 2: Summary of Possible In Utero Induced Deterministic Radiation Effects by Gestational Age and Radiation Dosage

IQ = intelligence quotient.

Iodinated Contrast

Iodinated contrast is regularly used in CT imaging and some cardiac catheterization procedures. Iodinated contrast crosses the placenta and, although it does not necessarily pose harm to a pregnant person or their fetus, it is recommended to avoid contrast use unless it will alter medical management.

Exercise Stress Testing

Pregnancy is not a contraindication to exercise testing; however, exercise should preferably be submaximal and non–weight-bearing (e.g., a recumbent bike). Consultation with an obstetrician or maternal fetal medicine specialist is helpful when there is uncertainty about safety. Contraindications to exercise testing include persistent vaginal bleeding, incompetent cervix, multiple gestation, placental previa after 26 weeks, pre-eclampsia/gestational hypertension, preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, and restrictive lung disease.

Conclusions

When taken in aggregate, the American Heart Association (AHA),4 American College of Cardiology (ACC), European Society of Cardiology (ESC),5 and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)6 recommend TTE and MRI without contrast as first-line modalities for cardiac imaging in the setting of pregnancy. These societies highlight that radiation exposure (usually through CT or nuclear medicine imaging) is often at a dose much lower than would be expected to cause fetal harm. Although it is important to be cognizant of fetal exposure, appropriate imaging should not be withheld if it is clinically indicated.

References

- Elkayam U, Goland S, Pieper PG, Silversides CK. High-risk cardiac disease in pregnancy: part 1. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:396-410.

- Bello NA, Bairey Merz CN, Brown H, et al.; American College of Cardiology Cardiovascular Disease in Women Committee and the Cardio-Obstetrics Work Group. Diagnostic cardiovascular imaging and therapeutic strategies in pregnancy: JACC focus seminar 4/5. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:1813-22.

- ACOG committee opinion no. 723: guidelines for diagnostic imaging during pregnancy and lactation. Obst Gynecol 2017;130:e210-e216.

- Mehta LS, Warnes CA, Bradley E, et al.; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Stroke Council. Cardiovascular considerations in caring for pregnant patients: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020;141:e844-e903.

- Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC guidelines for the management of cardiovascular disease during pregnancy. Eur Heart J 2018;39:3176-7.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Presidential Task Force on Pregnancy and Heart Disease and Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin no. 212: pregnancy and heart disease. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:e320-e356.

Clinical Topics: Noninvasive Imaging

Keywords: Cardio-Obstetrics