Development of an EMR-Based Registry to Define Cardiovascular Risk in South Asian Adults

Quick Takes

- The DILWALE (DIL Wellness and Arterial health Longitudinal Evaluation) Registry is the largest electronic medical record–derived dataset of South Asian Americans living in Texas (n = 31,781).

- South Asian adults have a high prevalence of known risk factors for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus.

- The DILWALE Registry adds additional data to help better inform prevention efforts in this population at higher ASCVD risk.

Commentary based on Agarwala A, Satish P, Ma TW, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in South Asians in the Baylor Scott and White Health DILWALE Registry. JACC Adv 2024;3:[ePub ahead of print].1

The risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) among individuals of South Asian (SA) ancestry is nearly twofold higher than in individuals of European ancestry.2 Existing risk-prediction tools such as the Framingham Risk Score and American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) Pooled Cohort Equations (PCE) for estimation of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk have limitations due to derivation from cohorts that contained little or no SA representation. As with other ethnic minority populations, SA populations are under-represented in research, resulting in health care practice with limited external validity and generalizability. Several cohort studies have sought to address gaps in these data.3,4 However, few have leveraged the use of electronic medical records (EMR)5 to create system-wide registries for data extraction and analysis.

In this setting, Agarwala et al. developed the DILWALE (DIL Wellness and Arterial health Longitudinal Evaluation) Registry from EMR data to comprehensively analyze risks of ASCVD and prevention opportunities in a real-world SA cohort.1 In a cohort of 31,781 individuals, they found the prevalence of ASCVD to be 7.1% and of premature ASCVD to be 2.5%. ASCVD was defined as coronary artery disease (CAD), myocardial infarction, history of percutaneous intervention, peripheral vascular disease, and stroke—of which CAD was the most prevalent. A high proportion of traditional risk factors were found at younger ages (Table 1), with premature ASCVD being diagnosed at a median age of 50 years. Notably, women with premature ASCVD were less likely to receive prescriptions for lipid-lowering therapy (statins or ezetimibe) than were men. Hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus were strongly associated with ASCVD and premature ASCVD.

Table 1: Prevalence of Risk Factors for ASCVD

Overall |

Men |

Women |

|

| Hyperlipidemia, % | 43 |

55 |

29.9 |

| Hypertension, % | 22.2 |

26.9 |

17.1 |

| Current smoking, % | 3.57 |

6.18 |

0.71 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 15.5 |

18.5 |

12.3 |

ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Commentary

Leveraging real-world EMR data, Agarwala et al. have established one of the largest SA cohorts to date, yielding new insights into cardiovascular (CV) risk and uncovering prevention opportunities. These data add to the growing body of evidence demonstrating the high prevalence of traditional risk factors in an SA population.1

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus was 15.5% in the DILWALE Registry, consistent with United States–based SA cohorts ranging from 8.9% to 25%. This high prevalence can in part be explained by genetic predisposition to insulin deficiency and lipodystrophy.6 Overall, diabetes mellitus was strongly correlated with ASCVD (odds ratio, 1.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.34-1.68), similar to data from other cohorts.2 Novel to the literature, diabetes mellitus was strongly correlated with premature ASCVD overall and in sex-specific analyses (Table 2). Herein exists an opportunity to mitigate the risk of ASCVD by focusing on diabetes mellitus prevention and treatment alongside culturally tailored lifestyle interventions.7

Table 2: Association of Risk Factors With ASCVD and Premature ASCVD

Overall |

Men |

Women |

||||

ASCVD |

Premature ASCVD |

ASCVD |

Premature ASCVD |

ASCVD |

Premature ASCVD |

|

| Hyperlipidemia, OR (95% CI) | 3.53 (3.01-4.17) |

6.19 (4.88-7.95) |

4.33 (3.52-5.37) |

8.07 (5.85-11.43) |

2.44 (1.87-3.2) |

3.791 (2.61-5.6) |

| Hypertension, OR (95% CI) | 3.48 (3.06-3.96) |

5.23 (4.39-6.25) |

3.53 (3.05-4.1) |

5.213 (4.26-6.4) |

3.44 (2.64-4.5) |

5.457 (3.79-7.92) |

| Diabetes mellitus, OR (95% CI) | 1.5 (1.34-1.68) |

1.33 (1.13-1.56) |

1.38 (1.21-1.58) |

1.22 (1-1.47) |

1.85 (1.5-2.28) |

1.72 (1.26-2.34) |

ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Hypertension prevalence was 22.2% in the DILWALE Registry, consistent with the prevalence in other cohorts.7 Hypertension was strongly correlated with ASCVD and premature ASCVD overall and in sex-specific analyses (Table 2), which is higher than previously reported (hazard ratio 1.95 in the UK Biobank [United Kingdom Biobank Study]).2 Indeed, an analysis of the MASALA (Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America) and MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) cohorts found a high prevalence (>50%) of untreated hypertension among SA individuals,8 offering significant opportunity for interventions aimed at lifestyle optimization and/or antihypertensive pharmacotherapy when appropriate.

The prevalence of hyperlipidemia was 43% in the DILWALE Registry and was strongly associated with ASCVD and premature ASCVD in all analyses (Table 2). Previous study data have shown high rates of dyslipidemia in SA patients due to elevated triglyceride levels, elevated total cholesterol levels, and lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels compared with levels in other racial and ethnic groups.7 Guidelines from the National Lipid Association (NLA) provide targets for primary prevention in SA patients based on their lipid risk profiles.9 These targets can be achieved through a combination of aggressive screening through validated risk calculators and coronary artery calcium testing, appropriately initiated pharmacotherapy, and proactive outreach to SA communities for linkage to care.

It is known that SA men typically have events roughly 10 years earlier than SA women, with the mean age of early myocardial infarction being 55 years of age.7 Although this mean age is younger than the median age reported in the DILWALE Registry (64 years in the overall cohort, 61 years for men, 68 years for women), it lends credence to addressing modifiable risk factors earlier and more aggressively according to available guidelines/recommendations.7 In those with ASCVD, there is staggering underutilization of lipid-lowering therapy. Undertreatment is magnified in populations at higher risk such as SA persons, evidenced by low utilization of lipid-lowering therapy in the DILWALE Registry cohort overall. Much of the decision regarding primary-prevention strategies is dependent on risk estimation with risk calculators that do not reflect SA individuals, contributing to the high rates of undertreatment.

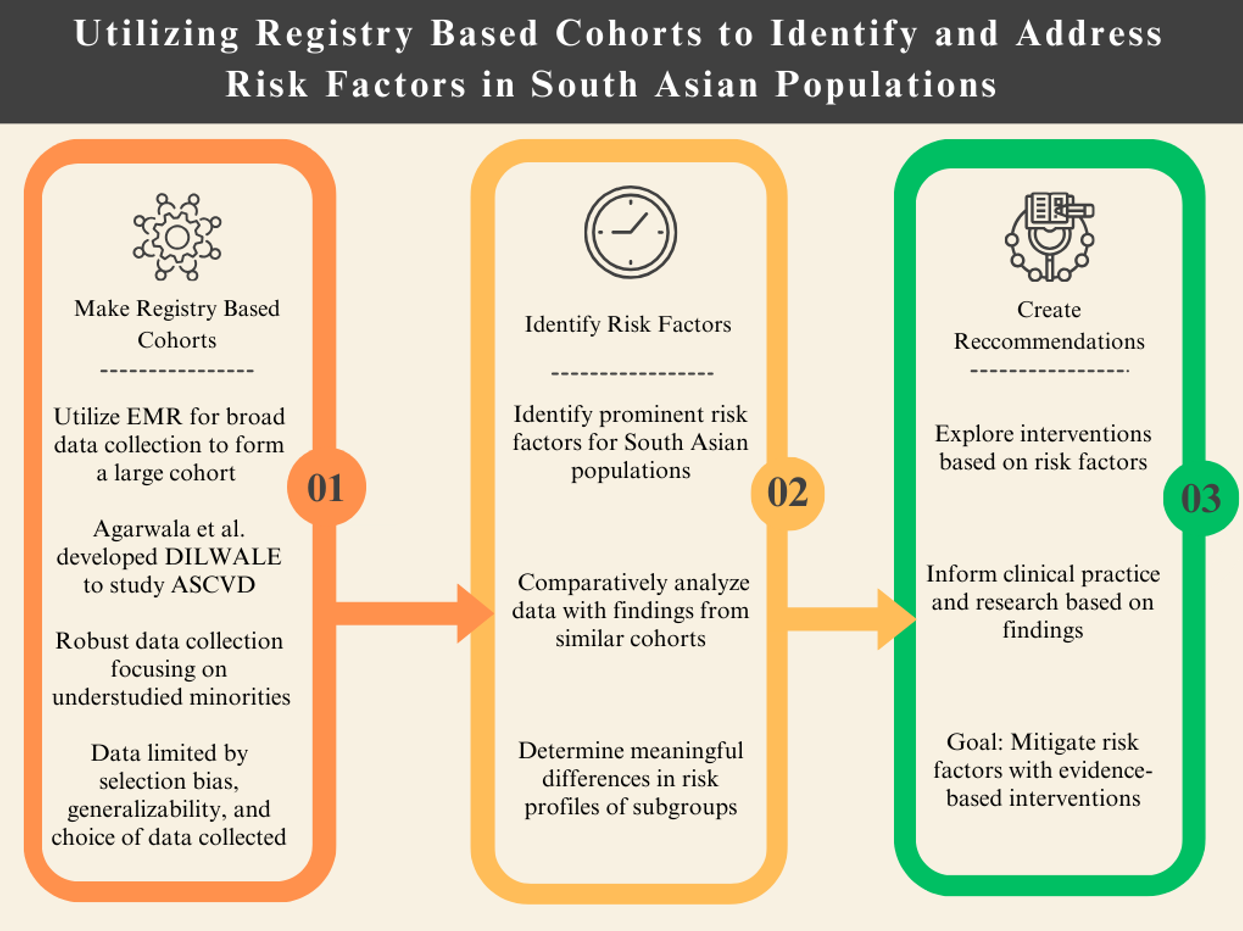

The use of EMR data to create the DILWALE Registry cohort allows for the study of ASCVD risk factors and treatment in a large SA cohort. Advantageously, EMR implemented for health management can allow for the identification of disease prevalence and patterns along with facilitating data sharing between hospitals and health care systems.10 Data from larger registries can also be leveraged in emerging artificial intelligence fields such as digital twin studies for CV prognostication, which require multimodal data to build accurate models.11 These studies use data to create simulations for patient care based on the unique clinical environment, which can predict disease risk and tailor randomized controlled trials. Furthermore, the lack of disaggregated data for SA subpopulations is an important issue that needs to be addressed in future research because there are meaningful differences in risk profiles between subgroups.2 Registry-based cohorts can provide more nuanced data because of their larger sizes and ability to capture minority populations that may be enriched in certain medical systems throughout the United States (Figure 1). Future research should include examining how well commonly used risk estimators such as the PREVENT (Predicting Risk of CVD EVENTs) score and PCE perform in these cohorts.

Figure 1: Utilizing Registry-Based Cohorts to Study South Asian Populations

The DILWALE Registry adds to a growing body of evidence that ultimately aims to improve the drivers of excess ASCVD risk and highlights the need for a proactive and culturally appropriate approach to cardiometabolic disease prevention in South Asian communities.

ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; DIWALE = DIL Wellness and Arterial health Longitudinal Evaluation; EMR = electronic medical records.

References

- Agarwala A, Satish P, Ma TW, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in South Asians in the Baylor Scott and White Health DILWALE Registry. JACC Adv 2024;3:[ePub ahead of print].

- Patel AP, Wang M, Kartoun U, Ng K, Khera AV. Quantifying and understanding the higher risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease among South Asian individuals: results from the UK Biobank prospective cohort study. Circulation 2021;144:410-22.

- Al Rifai M, Kanaya AM, Kandula NR, et al. Association of coronary artery calcium density and volume with predicted atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk and cardiometabolic risk factors in South Asians: the Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) study. Curr Probl Cardiol 2023;48:[ePub ahead of print].

- Satish P, Sadaf MI, Valero-Elizondo J, et al. Heterogeneity in cardio-metabolic risk factors and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease among Asian groups in the United States. Am J Prev Cardiol 2021;7:[ePub ahead of print].

- Beasley JM, Ho JC, Conderino S, et al. Diabetes and hypertension among South Asians in New York and Atlanta leveraging hospital electronic health records. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2021;13:146.

- Hodgson S, Williamson A, Bigossi M, et al.; Genes & Health Research Team. Genetic basis of early onset and progression of type 2 diabetes in South Asians. Nat Med 2025;31:323-31.

- Agarwala A, Satish P, Rifai MA, et al. Identification and management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in South Asian populations in the U.S. JACC Adv 2023;2:[ePub ahead of print].

- Patel J, Mehta A, Rifai MA, et al. Hypertension guidelines and coronary artery calcification among South Asians: results from MASALA and MESA. Am J Prev Cardiol 2021;6:[ePub ahead of print].

- Kalra D, Vijayaraghavan K, Sikand G, et al. Prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in South Asians in the US: a clinical perspective from the National Lipid Association. J Clin Lipidol 2021;15:402-22.

- Dornan L, Pinyopornpanish K, Jiraporncharoen W, Hashmi A, Dejkriengkraikul N, Angkurawaranon C. Utilisation of electronic health records for public health in Asia: a review of success factors and potential challenges. Biomed Res Int 2019;2019:[ePub ahead of print].

- Thangaraj PM, Benson SH, Oikonomou EK, Asselbergs FW, Khera R. Cardiovascular care with digital twin technology in the era of generative artificial intelligence. Eur Heart J 2024;Sept 26:[ePub ahead of print].

Clinical Topics: Prevention, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia

Keywords: Plaque, Atherosclerotic, Primary Prevention