When Lesions Go Deep: Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Cardiovascular Risk

Quick Takes

- Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is an underrecognized, chronic inflammatory skin disease.

- The link between HS, systemic inflammation, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) underscores the need for increased awareness of HS in the field of preventive cardiology.

- Studies addressing cardiovascular risk in HS and exploring the benefits of cardiovascular screening, inflammatory modulation therapies, and lifestyle interventions are warranted.

Background

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease affecting approximately 0.3-1.2% of the population,1 though underdiagnosis is common due to challenges in recognition and reporting. The condition is more common in women (3:1 ratio) and in the United States disproportionately affects those who identify as Black or Hispanic. Despite its prevalence and the well-documented burden of symptoms, the broader systemic implications of HS—particularly cardiovascular health—remain underexplored. Significant knowledge gaps persist regarding the mechanisms through which HS may contribute to cardiovascular and cardiometabolic morbidity. This underscores the need for more research into its systemic manifestations and the potential for targeted interventions to address these risks.

Pathogenesis, Disease Course, and Treatment

HS is characterized by tender, deep-seated nodules, formation of pus-discharging tunnels (sinus tracts), abscess formation, and fibrotic scarring. HS predominantly affects intertriginous regions, including the axillae, inguinal area, gluteal cleft, and inframammary folds (Image 1). The pathogenesis of HS is poorly understood but likely multifactorial, involving a complex interplay of genetic predisposition, immune dysregulation, and environmental triggers.2 The primary site of HS pathology is thought to be the hair follicle, where hyperkeratosis, occlusion, and follicle rupture trigger the inflammatory response. This process involves the recruitment of neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes, driving an excessive production of proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukins (IL) (IL-1 beta, IL-17, and IL-12/23).3 This cytokine activity perpetuates a cycle of inflammation, causing follicular destruction and tunnel formation that is often permanent. Like acne, HS is frequently complicated by bacterial colonization and is sometimes antibiotic-responsive or responsive to acute surgical intervention, though HS is not a true infection. Instead, it is thought to be driven by autoinflammation and inappropriate reaction of the body to commensal bacteria and other disease mediators.4

Image 1

Sinus tracts with active inflammation and stereotypical pinched scarring of HS in the inguinal folds of a young female patient.

HS = hidradenitis suppurativa.

Treatment aims to reduce the inflammatory response, alleviate symptoms, and prevent disease progression (Table 1). Despite the promising efficacy of inflammatory modulation therapies in HS, the disease remains profoundly undertreated.1

Table 1

HS Treatment Category |

Intervention |

Recommendation |

| Lifestyle modifications | Weight management | Generally recommended, although little is known about the disease-modifying potential of lifestyle interventions once HS has been diagnosed2,5 |

| Smoking cessation | ||

| Dietary changes | ||

| Systemic antibiotics | Tetracyclines | Recommended for mild-to-moderate HS, either for a 12-week course or long-term maintenance as appropriate6 |

| Rifampicin | ||

| Clindamycin | ||

| Moxifloxacin | ||

| Metronidazole | ||

| Ertapenem | ||

| Hormonal therapies | Spironolactone | Mainstay of therapy in female patients with more mild disease, or as adjuvants alongside biologic medications in more advanced disease6 |

| Oral contraceptives | ||

| Targeted biologics | TNF–alpha-inhibitor: adalimumab | FDA-approved for moderate to severe disease6,7 |

| IL-17A inhibitor: secukinumab | ||

| IL-17A/F inhibitor: bimekizumab | ||

| Targets currently being studied | IL-1 (alpha/beta and beta alone) | Undergoing phase 3 studies |

| IL-17 | ||

| JAK |

HS = hidradenitis suppurativa; TNF-alpha = tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IL = interleukin; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; JAK = Janus tyrosine kinase.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Cardiovascular Risk

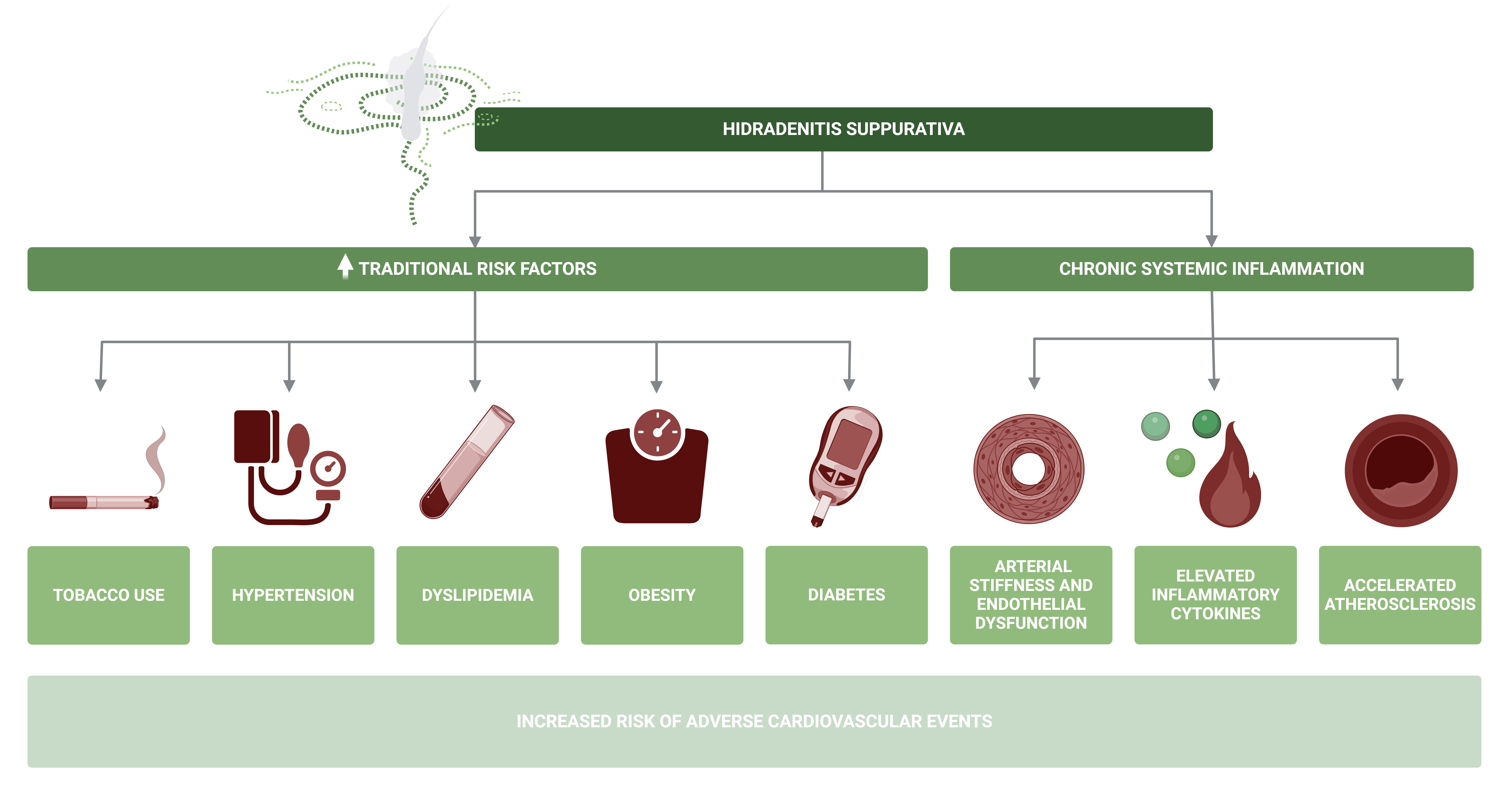

Individuals with HS exhibit a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, including obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, positioning those with HS at an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Figure 1).8,9 One meta-analysis has highlighted that HS is associated with metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions including abdominal obesity, hypertension, elevated blood sugar levels, and dyslipidemia, which itself is a well-established risk factor for CVD.10

Figure 1: Factors Thought to Contribute to Increased Risk of CVD in HS

Created in BioRender. Biering-Sørensen, T. (2025) https://BioRender.com/t84u744

CVD = cardiovascular disease; HS = hidradenitis suppurativa.

Retrospective cohort analysis data show that individuals with HS appear to have an increased risk of myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular events,11 and the association between HS and CVD is further supported by population-based studies that have reported a higher incidence of coronary artery disease and adverse cardiovascular outcomes among individuals with HS compared with the general population.12

The link between HS and CVD is partly driven by the chronic, systemic inflammation inherent to HS. Systemic inflammatory effects are thought to accelerate the development of atherosclerosis and induce atherosclerotic plaque instability through various mechanisms, including endothelial dysfunction and increased arterial stiffness (Figure 1).13-15 Given the chronic, low-grade inflammation characteristic of HS, these individuals may face a greater risk for cardiovascular complications independent of traditional risk factors.

Addressing the cardiovascular risk in individuals with HS remains an area of ongoing research. While there is preliminary evidence that anti-inflammatory treatments may contribute to improved cardiovascular health by addressing systemic inflammation and associated metabolic disturbances13 prevalent in HS, these therapies' full impact on patients with HS's cardiovascular health is not yet well understood. HS therapy may be complicated by the propensity for some treatments (specifically those targeting the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway) to improve HS while also potentiating dyslipidemia and potentially increasing the risk of venous and atherothrombotic events.16 Inflammatory modulation therapies, including those targeting the inflammasome, may improve endothelial function, reduce arterial stiffness, and improve lipid profiles, lowering the risk of cardiovascular events. However, further studies are needed to precisely assess the cardiovascular benefits of these therapies in individuals with HS.

Conclusions

HS is an underrecognized, inflammatory skin disease, and its chronic nature and accompanying symptom burden highlight the importance of early detection and management of HS and associated risk factors. Addressing cardiovascular risk in HS may be a critical component of overall management, and studies exploring the benefits of regular cardiovascular screening, lifestyle interventions, and anti-inflammatory treatments and their effect on cardiovascular health in individuals with HS are warranted. The link between HS, systemic inflammation, and CVD underscores the need for multidisciplinary approaches to improve quality of life as well as long-term health and reduce adverse outcomes for people living with HS. This begins with increased awareness of HS in general health practice, emergency and surgical settings, and the field of preventive cardiology.

References

- Nguyen TV, Damiani G, Orenstein LAV, Hamzavi I, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: an update on epidemiology, phenotypes, diagnosis, pathogenesis, comorbidities and quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021;35:50-61.

- Narla S, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH. The most recent advances in understanding and managing hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Res 2020;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-1049.

- Vossen ARJV, van der Zee HH, Prens EP. Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Systematic Review Integrating Inflammatory Pathways Into a Cohesive Pathogenic Model (Frontiers website). 2018. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02965/full. Accessed 02/24/2025.

- Colvin A, Petukhova L. Inborn errors of immunity in hidradenitis suppurativa pathogenesis and disease burden. J Clin Immunol 2023;43:1040-51.

- Charrow A, Barnes LA. Smoking cessation and hidradenitis suppurativa: advances and treatment gaps. JAMA Dermatol 2024;160:1039-40.

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;81:91-101.

- Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med 2016;375:422-34.

- Tzellos T, Zouboulis CC, Gulliver W, Cohen AD, Wolkenstein P, Jemec GBE. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational studies. Br J Dermatol 2015;173:1142-55.

- Lee JW, Heo YW, Lee JH, Lee S. Epidemiology and comorbidity of hidradenitis suppurativa in Korea for 17 years: a nationwide population-based cohort study. J Dermatol 2023;50:778-86.

- Phan K, Charlton O, Smith SD. Hidradenitis suppurativa and metabolic syndrome – systematic review and adjusted meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol 2019;58:1112-7.

- Reddy S, Strunk A, Jemec GBE, Garg A. Incidence of myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accident in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol 2020;156:65-71.

- Worapongsatitaya P, Chaikijurajai T, Ponvilawan B, Ungprasert P. Hidradenitis suppurativa and risk of coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Dermatol 2023;68:359-65.

- Moriya J. Critical roles of inflammation in atherosclerosis. J Cardiol 2019;73:22-7.

- Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, Tracy RP, Hennekens CH. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med 1997;336:973-9.

- McEniery CM, Spratt M, Munnery M, et al. An analysis of prospective risk factors for aortic stiffness in men: 20-year follow-up from the caerphilly prospective study. Hypertension 2010;56:36-43.

- Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, et al.; ORAL Surveillance Investigators. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2022;386:316-26.

Clinical Topics: Prevention

Keywords: Hidradenitis Suppurativa, Risk Assessment, Atherosclerosis