Catheter Repair of Superior Sinus Venosus Defect Associated With Partial Anomalous Venous Drainage: A Promising Alternative to Surgery?

Quick Takes

- In patients with sinus venosus defects who have favorable anatomy, transcatheter repair has good immediate- and mid-term outcomes.

- Long-term follow-up is necessary to monitor for possible complications.

- Continued improvement in stent technology will enhance procedural ease, improve success rates, and expand patient eligibility.

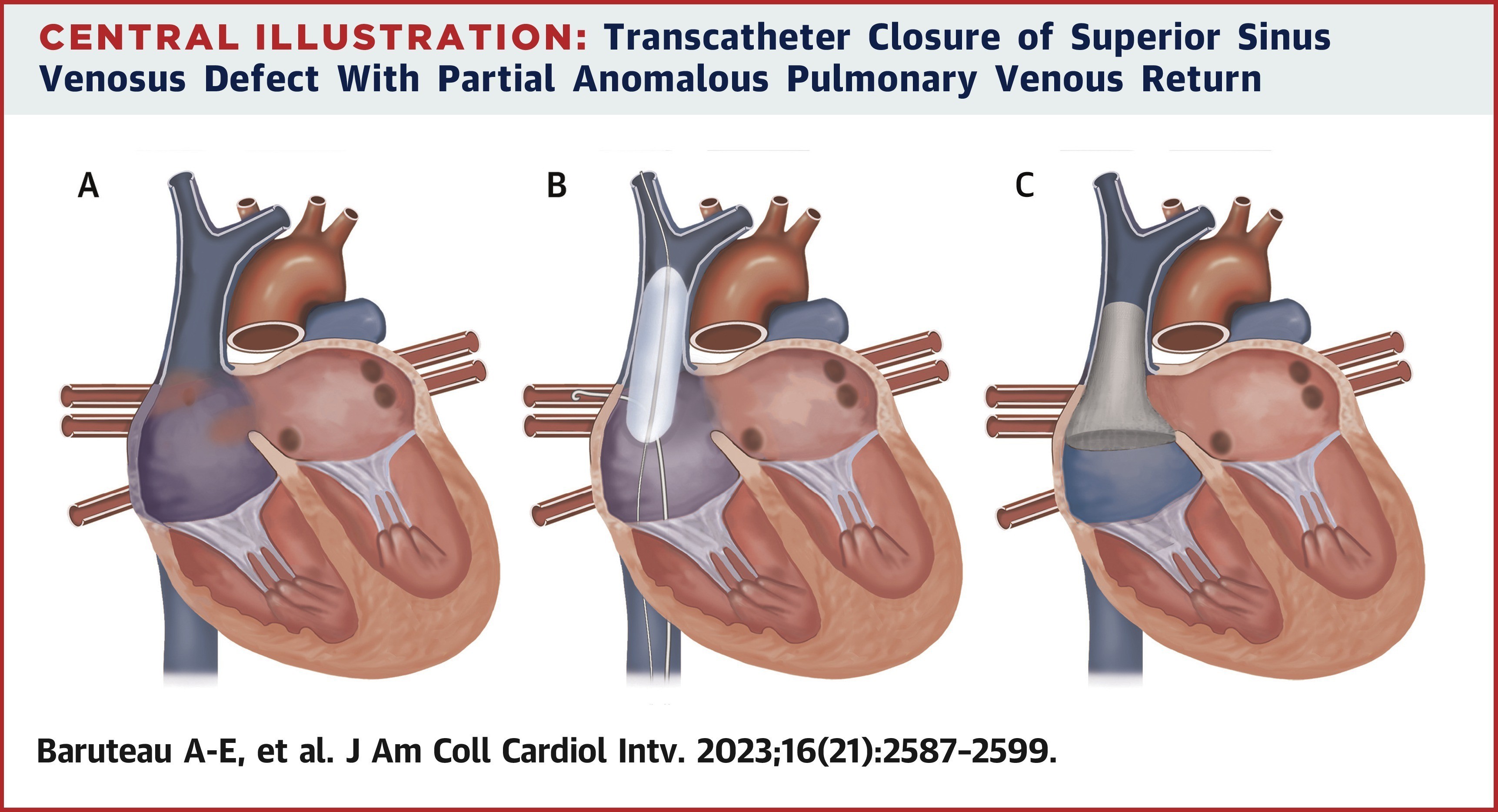

Transcatheter repair of superior sinus venosus defects (SVDs) associated with partial anomalous pulmonary venous drainage of the right upper/middle pulmonary vein (RPV) has gained popularity in the last 10 years.1 This lesion results from deficiency in the wall between the RPVs and the superior vena cava (SVC), allowing the veins to drain abnormally to the SVC-right atrium (RA) junction. Almost invariably, an interatrial communication is present and located posterior or posterosuperior to the fossa ovalis. Transcatheter closure of SVD is done through placing a long covered stent in the SVC-RA junction to close the defect, divert the SVC flow to the RA, and redirect the right upper pulmonary vein (RUPV) flow around the stent into the left atrium (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Transcatheter Closure of Superior Sinus Venosus Defect With Partial Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Return

Reprinted with permission from Baruteau AE, Hascoet S, Malekzadeh-Milani S, et al. Transcatheter closure of superior sinus venosus defects. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16(21):2587-2599. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2023.07.024.

Transcatheter closure of a superior sinus venosus defect with partial anomalous pulmonary venous return has become a safe and efficient alternative to open heart surgery in carefully selected patients, although worldwide experience remains limited (Panel A). The procedural concept is based on the crossroad formed by the abnormally connected right pulmonary veins, the SVC, the RA, and the left atrium (LA) above the level of the unroofed atrial septum (Panel B). Careful patient selection, especially balloon interrogation of the SVC along with continuous monitoring of the RUPV pressure, is key (Panel C). The transcatheter approach consists in placing a long covered stent in the SVC–RA junction to close the defect, diverting the SVC flow to the RA and redirecting the RUPV flow around the stent into the LA.

Since the initial report at the Congenital & Structural Interventions meeting by Hussein Abdullah in 2013 and the series from Evelina Children's Hospital in London,1 strategies have evolved to minimize stent instability and embolization as well as residual shunting. In an editorial comment, Benson et al.2 reflected on how transcatheter closure of atrial septal defects and patent arterial ducts has become first-line therapy for most children and adults, replacing surgical interventions2; until recently, SVDs were considered always surgical.

The well-known possible complications of surgical closure of SVDs (e.g., complications of cardiopulmonary bypass, sinus node dysfunction with the need for a pacemaker, stenosis or obstruction of RPVs and/or SVC) and the promising results of percutaneous treatment encouraged interventionists to work on refining the procedure to increase patient eligibility, achieve better results, and minimize complications.

Eligibility for transcatheter treatment is based on several factors, including but not limited to the absence of a large high-draining vein, SVC size of ≥16 mm, no significant caudal extension of the defect (with the vertical dimension exceeding the transverse cavoatrial dimension), and the absence of other cardiac defects requiring surgical intervention. Additionally, patients with a short distance between the upper end of the RUPV and the innominate vein may present challenges.3

Technical Challenges

The availability of equipment, particularly specific necessary stents, can occasionally restrict a patient's eligibility for the procedure or, at the least, introduce additional complexity to the process. The 10-zig Cheatham Platinum (CP) Stent™ (NuMED, Inc., Hopkinton, NY) offers the benefit of being available in custom lengths ranging from 5 to 11 cm and can be expanded up to 34 mm in diameter, with moderate shortening occurring at diameters <28 mm.4 However, only 5- and 6-cm stents received the Conformité Européenne mark and US Food and Drug Administration approval, and the longer versions are currently unavailable in many countries even though most SVD cases require stents >6 cm.4 The main characteristics of these stents have been summarized previously and multiple stents are being developed.3,5

The stent must be of sufficient length to securely appose the nonstenotic, distensible portion of the SVC cranially to prevent displacement, while also extending far enough caudally to cover the defect.

Confirmation of Pulmonary Vein Patency

A protective noncompliant balloon can be kept in the pulmonary vein during SVC stent implantation to prevent excessive stent bulging into the pulmonary vein.3 Another strategy is keeping a catheter in the pulmonary vein (retrograde or trans-septal) until complete closure of the defect and the rerouting of the anomalous vein with no obstruction is assured.

To streamline the process and minimize the risks and potential complications, additional preprocedure planning strategies have been introduced. This includes the use of 3D printing to create a physical model that mirrors anatomical and biomechanical characteristics.3 The model can also be integrated with a system to enable hands-on simulation, aiding in clinician training and optimizing procedural techniques. Additionally, virtual 3D simulation based on computed tomography (CT) scan data provides an accurate representation of the defect's anatomical structure for a more realistic evaluation.3

Postprocedure Follow-Up and Outcome

Patients typically receive ≥6 months of some form of anticoagulation, with aspirin therapy plus or minus addition of either clopidogrel or oral anticoagulants (either warfarin or nonvitamin K oral anticoagulant). The traditional follow-up includes clinical evaluation, electrocardiogram, and transthoracic echocardiogram done at 1, 6, and 12 months postprocedure. After 12 months, annual follow-up is recommended. Additional cross-sectional imaging with CT at 6-12 months postprocedure is recommended to confirm stent position and to rule out pulmonary vein obstruction.6 Cardiac magnetic resonance could be helpful during follow-up to assess right heart volume and remodeling as well as to check for residual shunting.

The rate of major complications in most case series (Table 1) ranges from 0% to 4%,7 and appears to be decreasing over time, with accumulated experience and the development of new techniques aimed at improving outcomes and enhancing safety.

Table 1: Outcomes in a Large Single-Center or Multicenter Series of Transcatheter Closure of Sinus Venosus Defect

| First Author, Year | N | Procedural Complications | Follow-Up | |||||

| Major Complications | Stent Migration | PV Obstruction | Other Life-Threatening Complication(s) | Follow-Up Duration (mo) | > Trivial Residual Shunt | Late Reintervention or Late Complication | ||

| Hansen, 20202 | 25 | 2 (8.0) | 1 (4.0)a | 0 (0) | 1 (4.0) Tamponadea |

16.8 (9.6-20.4) | 1 (4.0) | None described |

| Sivakumar, 202032 | 24 | 4 (16.7) | 3 (12.5)a,b | 0 (0) | 1 (4.2) Left innominate vein occlusionb |

20 (3-54) | 0 (0) | None described |

| Rosenthal et al, 202129 | 75 | 4 (5.3) | 2 (2.7)a | 1 (1.3)a | 1 (1.3) Tamponadea |

21.6 (2-61.2) | 5 (7) | None described |

| Hejazi et al, 202233 | 14 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16.5 (0.5-31.5) | 0 (0) | None described |

Reprinted with permission from Baruteau AE, Hascoet S, Malekzadeh-Milani S, et al. Transcatheter closure of superior sinus venosus defects. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16(21):2587-2599. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2023.07.024.

Values are n (%) or median (minimum-maximum) unless otherwise indicated. Major complications defined as stent migration, PV obstruction, and/or other life-threatening complication. Citation numbers are from the Baruteau et al. paper.

PV = pulmonary vein.

a Transcatheter management.

b Surgical management.

Stent stability has been an important focus among interventionalists. It is now widely acceptable that the longer the stent in the SVC (so that there is more apposition between SVC wall and the stent), the less likely is the need for additional anchoring stents. In their international registry, Rosenthal et al. reported the need for additional stents in 62% of patients initially treated with 6 cm 10-zig CP stents, compared with only 23% in those treated with 7.5-8 cm 10-zig covered stents.4 Periprocedural stent migration, especially while inflating the caudal end of the stent, has been a concerning issue. Several techniques have been developed to overcome this problem, such as an overlapping stent to anchor the initial 10-zig stent,1 the temporary suture-holding technique,8 and the chimney double stent technique.9

Surgery for superior SVDs is generally considered low risk, with a postoperative mortality rate of <1% and excellent long-term outcomes.7 In a study by Brancato et al.,7 a single-center experience was reported comparing surgical and catheter-based approaches, with follow-up assessments at both short- and medium-term intervals. Among the 36 patients deemed suitable for transcatheter treatment, 97% had successful stent implantation. Procedure failure in two patients was due to pulmonary vein obstruction. The length of intensive care unit and hospital stays was significantly shorter in the transcatheter group. Procedural and in-hospital complications were more frequent in the surgical group. All patients showed improvement in the right ventricular size and unobstructed pulmonary venous return. No late complications were reported in either group.

Sandoval et al. reported the first two patients to have sinus node dysfunction during or after transcatheter intervention.10 One happened during balloon inflation in the SVC. The other patient had sinus pauses a few hours after the procedure for which the patient underwent pacemaker implantation.

Sagar et al.6 reported their single-center experience and the evolution of procedural modifications over an 8-year period in 100 patients. Transesophageal echocardiography and CT were done as preprocedural assessments. With the learning curve, the rate of suitability for transcatheter closure went up significantly.6

Transcatheter closure of SVDs has evolved with growing global experience, and short- and mid-term outcomes are promising. The procedure can be done safely in any patient with an SVC diameter of ≥16-18 mm. Long-term follow-up is still needed before this approach can be considered a definitive alternative to surgery (Figure 1).

References

- Hansen JH, Duong P, Jivanji SGM, et al. Transcatheter correction of superior sinus venosus atrial septal defects as an alternative to surgical treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(11):1266-1278. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.070

- Benson L, Horlick E, Osten M. Percutaneous repair of the sinus venosus atrial defect: usus est magister optimus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(11):1279-1280. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.01.024

- Baruteau AE, Hascoet S, Malekzadeh-Milani S, et al. Transcatheter closure of superior sinus venosus defects. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16(21):2587-2599. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2023.07.024

- Rosenthal E, Qureshi SA, Jones M, et al. Correction of sinus venosus atrial septal defects with the 10 zig covered Cheatham-platinum stent - an international registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;98(1):128-136. doi:10.1002/ccd.29750

- Morgan GJ, Zablah J. A new FDA approved stent for congenital heart disease: First-in-man experiences with G-ARMORTM. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;100(7):1261-1266. doi:10.1002/ccd.30447

- Sagar P, Sivakumar K, Thejaswi P, Rajendran M. Transcatheter covered stent exclusion of superior sinus venosus defects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83(22):2179-2192. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2024.03.417

- Brancato F, Stephenson N, Rosenthal E, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical treatment for isolated superior sinus venosus atrial septal defect. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;101(6):1098-1107. doi:10.1002/ccd.30650

- Hejazi Y, Hijazi ZM, Saloos HA, Ibrahim H, Mann GS, Boudjemline Y. Novel technique for transcatheter closure of sinus venosus atrial septal defect: the temporary suture-holding technique. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;100(6):1068-1077. doi:10.1002/ccd.30415

- Pascual-Tejerina V, Sánchez-Recalde Á, Cantador JR, López EC, Gómez-Ciriza G, Gutiérrez-Larraya F. Transcatheter repair of superior sinus venosus atrial septal defect with partial anomalous pulmonary venous drainage with the chimney double stent technique. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2019;72(12):1088-1090. doi:10.1016/j.rec.2019.08.004

- Sandoval JP, Rosenthal E, Arias E, et al. Sinus node dysfunction during transcatheter assessment and stent correction of sinus venosus atrial septal defects. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;102(4):683-687. doi:10.1002/ccd.30790

Clinical Topics: Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Congenital Heart Disease, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention

Keywords: Heart Septal Defects, Atrial