Wildfire Smoke-Related Fine Particulate Matter Linked to Higher Risk of HF

Long-term exposure to wildfire smoke-related fine particulate matter (defined as PM2.5) was linked to a higher risk of heart failure (HF) in older adults compared with non-wildfire smoke PM2.5, according to a new study published in JACC. Furthermore, women and socially vulnerable populations were more susceptible.

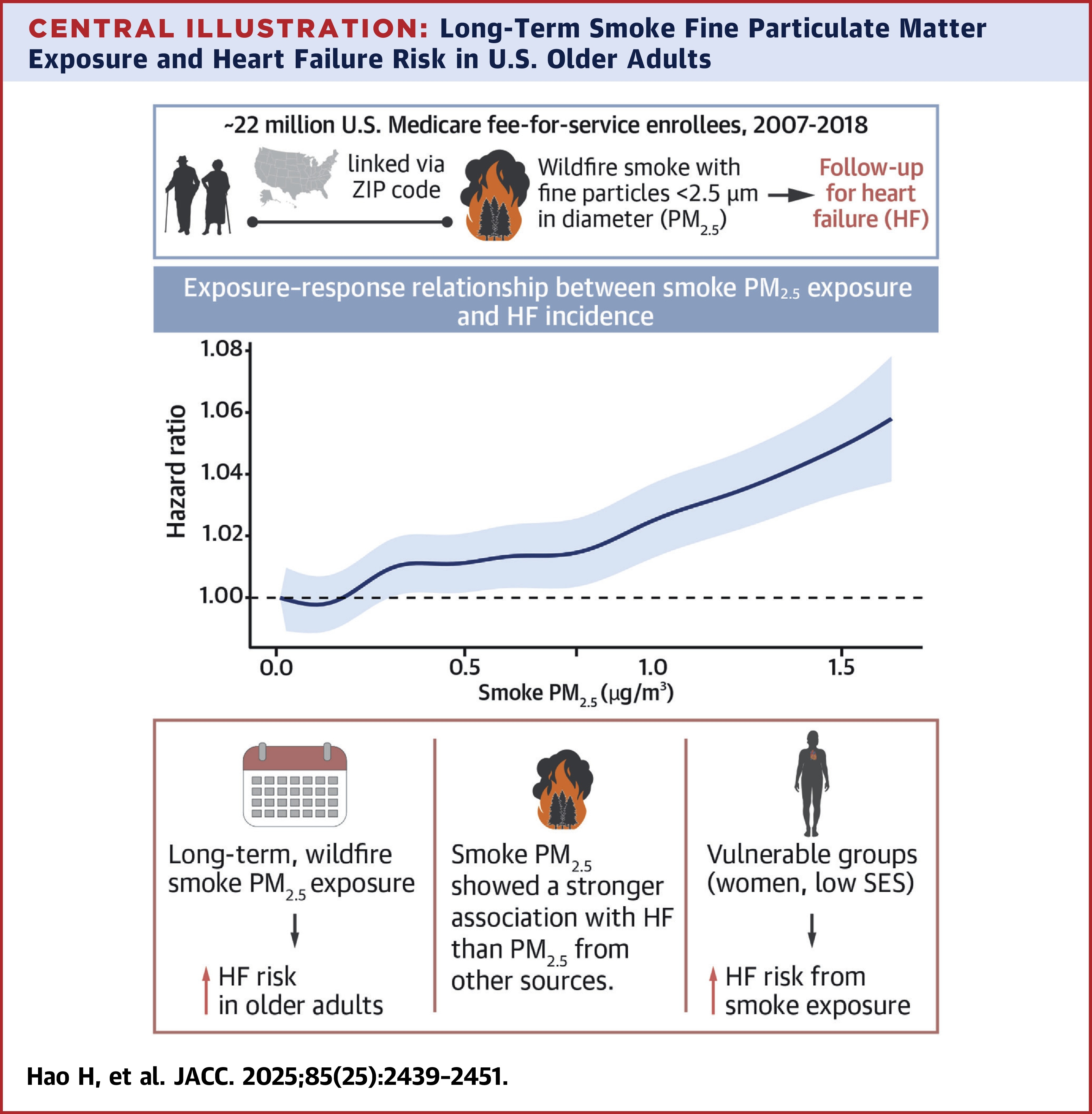

In the national retrospective cohort study, Hua Hao, PhD, et al., analyzed data on the 22 million Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years of age (mean age 74; 58% women; 88% White, 6% Black; 10% eligible for Medicaid) enrolled in the Fee-For-Service program from 2007 to 2018. They linked individuals to exposure estimates for both wildfire smoke and non-wildfire smoke PM2.5 over a two-year period based on air pollution levels by ZIP code.

The moving two-year average wildfire smoke PM2.5 exposure was 0.51 μg/m3 and 8.52 μg/m3 for non-wildfire smoke. Participants had an average of 83 days per year with wildfire smoke exceeding 1 μg/m3 and it exceeded 2.5 μg/m3 for 20 days. Median follow-up was five years with a total follow-up of 115 million person-years covering five million HF events.

Results showed that the increased risk for HF was significantly associated with both wildfire smoke and non-wildfire smoke elevated PM2.5 levels. The risk was higher for wildfire smoke than for non-wildfire smoke, with an increase in the hazard ratio per each 1 μg/m3 increase of exposure of 1.014 vs. 1.005, suggesting potentially greater relative toxicity for wildfire smoke exposure. This corresponds with an estimated 20,238 additional HF cases annually among older adults. The association was stronger in women, Medicaid-eligible participants and those living in lower income areas.

Additionally, the number of days exposed to wildfire smoke PM2.5 at both the 1 μg/m3 and 2.5 μg/m3 levels was also significantly associated with an elevated risk of HF.

"This study highlights the critical need for targeted interventions to mitigate the health impacts of smoke, particularly among the most vulnerable populations, and underscores the importance of considering both social determinants of health and environmental justice in these efforts," write Hao, et al., who call for public health strategies like "[i]mproved air quality regulation, enhanced community interventions, and expanded health care resources," to mitigate risk.

"By century's end, under a high greenhouse gas emission scenario, we expect 74% of the globe to experience substantial increases in the length of wildfire season and the frequency of wildfire events," write Joan A. Casey, PhD, and Marianthi-Anna Kioumourtzoglou, SCD, in an accompanying editorial comment. "This is already the case in the [U.S.], where wildfire smoke days, once rare, now happen several times per year."

"This study highlights a growing and underappreciated threat to heart health," adds Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, SM, FACC, Editor-in-Chief of JACC. "As wildfire smoke becomes more frequent and intense, we are learning that even small, long-term exposures can raise the risk of heart failure, especially among the most vulnerable. These findings elevate the urgency of protecting communities through both environmental policy and health care preparedness."

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Acute Heart Failure

Keywords: Particulate Matter, Air Pollution, Wildfires, Smoke, Heart Failure

< Back to Listings