Academic Profiles: Voices in Academic Medicine During COVID-19

Voices in Academic Medicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Interviews With Leaders Who Work at the Front Lines and Lead by Example During the Pandemic

Ashish Correa, MD, is the chief cardiology Fellow in Training (FIT) at Mount Sinai Morningside Hospital in New York City, NY. He received his Medical Doctorate at Grant Medical College in Mumbai, India, and completed both internal medicine residency and chief residency at Mount Sinai Morningside. Supplementing his academic activities and research, Correa frequently creates medical illustrations. He will be applying for training in advanced heart failure, mechanical circulatory support and cardiac transplantation this Fall.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic hit New York City in March 2020, and since then, academic medicine across the city has been forced to rapidly adapt and transform itself. Hospitals have faced many logistic challenges – an unremitting surge of sick patients, limited space, scarce personal protective equipment (PPE), limited ventilators, staff shortages due to illness and unavoidable fiscal fallouts. Individual departments and their divisions have had to confront unique challenges. Various disciplines like internal medicine, emergency medicine and critical care medicine formed the vanguard in this battle. Early in the pandemic, cardiology teams were also deployed to the front lines, in a large part due to their familiarity with intensive care. Finally, many other departments also had to deploy staff to care for the ever-growing number of sick patients. This required dramatic changes in staffing responsibilities, rethinking of schedules, cancelation of routine academic activities and a general re-invention of what it means to practice academic medicine.

Now, as the worst of the outbreak moves away from New York, we have the opportunity to take stock and learn from the experiences of the last few months. To gain a better understanding of how academic medicine (especially academic cardiology) underwent this emergency transformation and how to find its way back, we decided to speak to three physician leaders in key areas of academic medicine – Gregg W. Stone, MD, FACC, in clinical research; Samuel L. Seward Jr., MD, in academic administration; and Vaani P. Garg, MD, in graduate medical education.

Gregg Stone, MD

Gregg W. Stone, MD, FACC, is the director for academic affairs for Mount Sinai Heart in the Mount Sinai Health System. Additionally, he is the co-director of medical education and research at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation and the co-director of Transcatheter Therapies. Stone received his Medical Doctorate at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. He then did his internship and residency at Cornell in New York City, and trained in cardiology at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles and in angioplasty at the St. Luke's Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City. Stone has authored thousands of manuscripts, abstracts and chapters, and has been the lead principal investigator of more than 100 national and international clinical trials.

"The COVID-19 pandemic has affected every aspect of the clinical research enterprise, from initiating new clinical trials, to enrolling patients in trials, to following up patients that have been previously enrolled. The pandemic has had major effects on everything I do as a researcher."

Dr. Stone, what have been the main challenges to conducting clinical trials and research during the pandemic over the last few months?

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected every aspect of the clinical research enterprise, from initiating new clinical trials, to enrolling patients in trials, to following up patients that have been previously enrolled. In terms of ongoing trials, patient enrollment ground to a halt. As for patients already enrolled in clinical trials, if they developed COVID-19 they would have a much higher risk of major adverse events, both cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular. These outcomes may be difficult to adjudicate. Were they related to their underlying cardiovascular disease or to COVID-19? This is important to tease out in cardiovascular research. So, for patients who were previously enrolled, we have been working with sponsors to rapidly collect PCR and/or serologic data to determine whether enrolled patients have or had COVID-19. We are also working on developing new adjudication paradigms if patients do get COVID-19 – are events related to COVID-19 included or excluded? And finally, we are developing new statistical analysis plans to adjust for the development of COVID-19.

In this regard, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has been very accommodating. They understand that the types of follow-up visits and tests that may have been required will not be able to be completed with the same efficiency or timeliness that had been previously planned. I believe that there will be a grace period where research will have to be interpreted in light of the pandemic.

At the same time, we have been organizing new studies. If anything, we have had more time to plan these trials. But we are uncertain about the timeline as to when we can start enrolling patients. In addition, sponsors have been hit hard and have had to reduce their research budgets, often delaying or cancelling planned research.

What about COVID-19-related research?

We have been quickly writing study protocols and submitting them through the appropriate regulatory authorities. But, to an extent, I believe an opportunity has been missed. When we were initially facing the pandemic, given the high morbidity and mortality we applied a shot-gun approach to therapy – e.g. starting everyone on hydroxychloroquine based on preclinical activity. Sadly, the evidence base for this approach was not established. Unfortunately, reliable comparative effectiveness evidence cannot be generated from non-randomized trials. In hindsight, we should have started randomized trials as soon as possible after the pandemic started. We need robust clinical trials to examine effectiveness vs. safety outcomes – only with high quality randomized data can we practice sound medicine. Had we relied on our principles to require randomization from the start, we could have completed meaningful single center or multicenter trial randomized trials by now. Unfortunately, we are not nearly as far along as we should otherwise be. However, these trials are slowly getting done, and we will get the answers. These thoughts are not to be critical, but to apply these learnings for future situations.

What do you think the intersection between COVID-19 research and cardiovascular research will be in the future?

This remains to be seen, but COVID-19 has numerous cardiovascular manifestations. Its primary effects on the lungs have secondary effects on the right side of the heart, and pulmonary arteriolar and venous thrombosis may be major issues. There are cardiac manifestations of COVID-19 including myocarditis related to cytokine storm – although clear evidence of viral infection of the myocardium is yet to be seen. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy has been reported to occur with increased frequency. Many patients are presenting with type 2 myocardial infarction (MI). Whether COVID-19 is associated with increased rates of plaque rupture or epicardial coronary thrombosis is still uncertain. Obviously, we have seen fewer patients present with STEMI, likely because patients' reticence to be seen at the hospital. Many patients with severe STEMI are presenting late and we are seeing mechanical complications of acute MI at a frequency have not seen in decades. So, there is a strong intersection between COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease. We have a lot to still understand, but it is clear that cardiovascular disease and COVID-19 will be inextricably linked as long as the virus persists.

How has the pandemic affected the execution of your work personally?

I was a medical resident from 1982 through 1985, in the middle of the HIV/AIDS crisis. I trained in New York City at Cornell/New York Hospital and we had entire floors dedicated to HIV patients. That went on for years with no cure and no vaccine. It was terrible, but it was never to the extent that we saw at the peak of the COVID-19 crisis, with 80-90% of the hospital dedicated to affected patients.

The pandemic has had major effects on everything I do as a researcher. On the positive side, there have been increased efficiencies as we are not wasting time in airports and on flights or recovering from jet lag and so on. Conversely, there are limitations in developing research concepts, planning and performing projects and education by not being together. In academic research, no one does it alone; collaboration is essential. Now, everyone has to collaborate through ZOOM, over the phone and email, or through social media. While that has been partially effective, it is not quite the same as being with your colleagues in the same room.

Another aspect is that some researchers have had a lot of time on their hands. I have been overwhelmed with the number of really good manuscripts to review that people have now had the time to complete. While it may be efficient sitting in front of a computer screen and doing nothing but research for 12 hours a day, it can also be quite monotonous, and that can be deleterious in terms of fostering creative thought. Furthermore, not only are we responsible for our regular work, but COVID-19 research has rightfully taken up an increasing amount of time. Many of the leading journals have been overcome with the number of COVID-19 related articles that are being submitted (up to 100 or more per day!), making it difficult to focus on non-COVID-related submissions. This will affect what will be published for some period of time.

Samuel L. Seward, Jr., MD

Samuel L. Seward Jr., MD, is a professor of medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. He serves as the Site Chair of the Department of Medicine at Mount Sinai Morningside and Mount Sinai West Hospitals. Seward received his Medical Doctorate at the University of Texas Southwestern School of Medicine in Dallas and trained in internal medicine and pediatrics at the former St. Vincent's Hospital Center in New York. He is a leading expert in Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome, a rare autosomal recessive disorder. Seward lives with his family in Princeton, NJ.

"My broad experience – and this didn't surprise me at all – was that everyone wanted to raise their hand and help. For most doctors I know, they felt that responding to this crisis was consistent with their original calling to medicine."

Dr. Seward, the COVID-19 pandemic probably had a huge impact on your medicine faculty, who were at the front lines of this crisis. How did you keep them motivated during these undoubtedly challenging times?

My broad experience – and this did not surprise me at all – was that everyone wanted to raise their hand and help. So, our task during the pandemic was to take practitioners who were used to being in certain specific practice settings – for example, the endoscopy suite or the outpatient setting – and move them completely to the inpatient setting. And we had to do that really wholesale. But honestly, this was not difficult. And this is one of the things I love about working with health care providers: they immediately recognized that we were in a crisis, and it is in their core to want to help and to try and figure out ways to be helpful.

Having said that, it was indeed challenging in some ways. We had some people we deployed to the inpatient setting who had not been ward attendings in more than 15 years. I had some people tell me how they had not been in the ward setting since they were trainees themselves. So, we had to think a lot about who we teamed people up with so that they felt supported and so that we were providing the best health care services to our patients.

Have you been in contact with other department chairs or other similarly placed leaders in medicine across the country to see what they have been doing and how they have been handling the crisis?

Not in any formal way, but I have heard from colleagues – other chairs and department heads – and I would share some of our experiences with them and they would share theirs with me. One example is our new pulmonary chief coming in from Spain, due to arrive after Labor Day. Spain was really experiencing a crisis, much as we were here in New York City. He and I ended up corresponding relatively frequently, starting in March. He talked about his experiences and shared about how they were handling the volume of patients coming to their hospital. That was useful to me, and I hope those correspondences were useful for him as well.

How did you keep the morale up in such a huge department, practicing at multiple different sites?

In the moment of the crisis, during the initial wave, I did not personally perceive morale to be a huge issue for our faculty. For most doctors I know, they felt that responding to this crisis was consistent with their original calling to medicine. Even with PPE, people were very aware that there was a shortage and were anxious about that, but it was not like my phone was ringing off the hook. People recognized that it was an issue and felt "we've gotta do what we've gotta do."

Now that we are out of that first wave and we are in this sort of lull, we are starting to see some things – people are exhausted; people are trying to process all the sadness and tragedy that they have seen. We are actively thinking how we can help with that. We have a number of resources available, but what people seem to need is an opportunity to debrief among themselves and an opportunity to truly spend time with their families and just get away for a bit. So, we have been encouraging people to truly take time and unplug for a few days or longer.

It clearly feels like we are in a different phase now in New York. But do you feel like there will be any lasting changes in your department or will things go back to the way they were before?

There have been certain changes that I see as positive. For example, among the medicine leadership, we had been doing daily calls, which we have now reduced somewhat in frequency. We were also doing all-faculty calls, which we now do every other week. The pandemic resulted in us coming together as a community. I do not think there is anything that we could have manufactured that would have had such a positive effect.

Another big change was a shift to telehealth. Even before the pandemic, we were planning to shift some of our services to telehealth to some extent, but now we have made a move to it in a big way. For instance, last week, the medicine department did more than 1,000 telehealth visits. If you rewind back to last Fall, we were doing well under a 100-such visits a month. We think this is going to be a lasting change. We have a busy working population, and I am sure they are looking for opportunities to engage with us not in person. I think in the long-term, this is going to be a major part of the way we deliver healthcare in the 21st century.

If I may ask, how did the pandemic affect you personally?

Well, it really did reinforce my love of medicine. You know, I did get sick; sick enough that I had to stay away from work for a bit. That was unsettling for my family. It was one of those moments where I felt like I was not doing enough and I wanted to do more. None of us likes to feel that way. Physicians always want to feel maxed out. That is sort of the way we are built. It was hard for me. Though all I wanted to do was be on the front lines – and I did do some of that – I realized that I had to really step back then. I realized that my role then was really administrative, and I had to commit to that. That was me taking stock of what my responsibilities were and doing what I could under the circumstances.

What advice would you give to other departmental heads across the country?

I think it is to really prepare for the worst. Getting into the train of thought, "Let's hope it's not that bad for us, but let's opt to prepare for the worst scenario." At least on paper, see if you are staffed for that scenario. Early on, plan for issues like supplies of PPE, supplies of ventilators. Recognize that there are going to be major fiscal impacts. Of course, have a lot of confidence in your staff. Use the experiences of institutions like ours that have already faced this crisis and prepare yourself. Most importantly, prioritize life! Because this is a deadly illness, and when you prioritize life, a lot of other stresses fall away.

Vaani Garg, MD

Vaani P. Garg, MD, is an associate program director of the Cardiovascular Diseases Fellowship Program at Mount Sinai Morningside/Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City and is the director of the clinical track of the Fellowship Program, based at the James J. Peters Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Bronx, NY. She received her Medical Doctorate at Tufts in Boston and trained in internal medicine and cardiology at Mount Sinai. Garg is a mother of two and lives on New York's Upper West Side.

"As a mother of two young kids, we – my husband and I – had to make a decision early on, when the pandemic hit: whether they would stay with me or move and stay with family. ... For me, as a young attending and junior faculty in my first two years as a program leader, I felt a duty to protect my fellows and be there when needed. You just show up. ... So that was the hard decision we made: for a month, my husband – he was incredibly supportive – he would be the one showing up for my kids, and I would be the one showing up for my fellows. But it was a struggle. It was incredibly rewarding as a program leader, but it was very taxing as a mom."

Dr. Garg, due the pandemic, so much of fellowship time has been lost. For the fellows who are continuing training beyond this academic year, do you think they will be able to catch up? And for those who are graduating, do you think that there will be a gap in their knowledge, and that they will be at a disadvantage?

Well, the total time we have spent deployed in managing COVID-19 has been around two months. In the aggregate of three years of training, that is not too much. I spent two months on maternity leave after the birth of my daughter during fellowship. And that was a real gap – I did nothing except care for my child. Yet, I graduated competent, confident and strong. It was through adding on additional work and training in areas where I felt I had a deficit. I feel something similar can apply for our fellows should they feel the need.

However, I honestly do not think they will. I do not think this time "lost" will compromise training or competence. What is interesting is that COVID-19 is something the world has never seen before and our fellows will have had the opportunity to train in a pre- and post-COVID world. The way cardiology is practiced now will be fundamentally different. That is a unique environment to train in.

But we have to make sure our fellows' fundamental understanding of basic cardiology is strong since they are going to have to add layers on top of post-COVID cardiology. That is where we as educators have to step up – to make sure that the basic knowledge of our trainees has been firmed up, so that adding on COVID-related cardiology is fun and exciting, and not anxiety-provoking.

How did the pandemic affect you personally?

It definitely affected me. As a mother of two young kids, we – my husband and I – had to make a decision early on when the pandemic hit: whether they would stay with me or move and stay with family. My husband works for the State and he is an essential worker, but he could work from home. Moving my kids and him out of New York City was not so much to decrease their risk of getting sick, though that was definitely a major factor, but rather to increase my availability. As a young attending and junior faculty in my first two years as a program leader, I felt a duty to protect my fellows and be there when needed. You just show up. When someone is struggling, you just want them to know that someone is there behind you, sitting in their office and available for you to swing by and just chat with. Being able to show up was a priority for me, and that would not have been possible if my kids were at home because I would need to show up for them.

So that was the hard decision we made: for a month, my husband – he was incredibly supportive – would be the one showing up for my kids and I would be the one showing up for my fellows. However, it was a struggle. It was incredibly rewarding as a program leader but very taxing as a mom. My kids were very proud that I was in the city fighting coronavirus but they are also very young. I could not be there tucking them in at night, making sure that they felt safe. Yet, I had comfort of knowing that my husband was there doing just that.

How do you think the COVID-19 pandemic affected the cardiology program – the fellows in particular? What did the program do to alleviate these challenges and keep the fellows motivated during the pandemic?

I think the pandemic affected our fellows in various different ways – clinical, personal and in the home. In terms of clinical issues, their work switched from cardiology work to COVID ICU work very rapidly, and that became the majority of their clinical responsibilities. Everything else was put on hold! Our fellows absolutely rose to that challenge. They were curious, engaged and really embraced these changes, despite the fact that they were no longer going to work in their chosen field and they did not know how long that would last.

Then in terms of personal struggles, they first had to reconcile their own feelings of anxiety and balance those against their desire to help. Then, some of them ended up getting COVID-19. So, we had some fellows who were here in the hospital, on the front lines putting themselves at risk daily, and others who were home sick with symptoms and itching to be in the hospital working in the trenches. Those struggles were different and very particular.

The last category is family. Many fellows were worried about elderly parents, kids, spouses and partners, and potentially exposing them. There many ways the pandemic affected our fellows.

In terms of alleviating those challenges, one of our biggest strengths is that we have many levels of leadership in our large program, all of these multiple point-people made us more effective in maintaining contact with the fellows. We checked in on the fellows repeatedly – by text or in person. Multiple times a day. Sometimes I was worried we were being overly intrusive, but the frequent check-ins were always well received. Secondly, we made an emergency work schedule for the fellows, with sections of time in the hospital and sections of mandated time off at home to give you a respite before you came back to work.

Finally, the daily online meetings that Dr. Narula (Chair of Cardiology) held were on the calendar every day – and sometimes it felt, gosh, another meeting, another meeting! But you know what? It kept your head in the game. As attendings and fellows, it made us feel that our thoughts and voices could be heard by the hospital leadership, because he would go around asking for the inputs of everyone on the call. And that was a true example of leadership.

Do you have avenues of communication with other cardiology program leaders across the nation – to see how they are doing and what they are doing?

Actually, the ACC started a list-serve of program directors at the start of the pandemic and it has been phenomenal. Program directors can pose questions or share what they have been doing – the information-sharing has been incredible. There has never been a venue for the sharing of knowledge like this before, and the timing has been perfect! When the pandemic hit the U.S., there were daily regular messages of support and advice from program leaders across the nation, and that was just tremendous.

What is the one piece of advice you would give other program leaders that have yet to face the fallout of the pandemic?

My biggest piece of advice is to reach out to all your networks and be okay with leaning on others, so that you can lead your own folks. The example I will give is that when all of this started, I put together all the information I had from Mount Sinai in terms of needs – supplies, donations, mask, child care, etc. I composed an email and sent it to every single contact in my Gmail account. I sent it to everyone – whether I had last spoken to them the previous week or 15 years ago. The response was amazing. I made and remade so many connections. It kept me motivated and kept my mind occupied, but it also resulted in benefits for my institution, and these acts of generosity powered us. It made us realize that the world cared about us and we could continue doing what we were doing. So, what I would say is, don not hesitate to reach out for support because it will help you lead better when you need to.

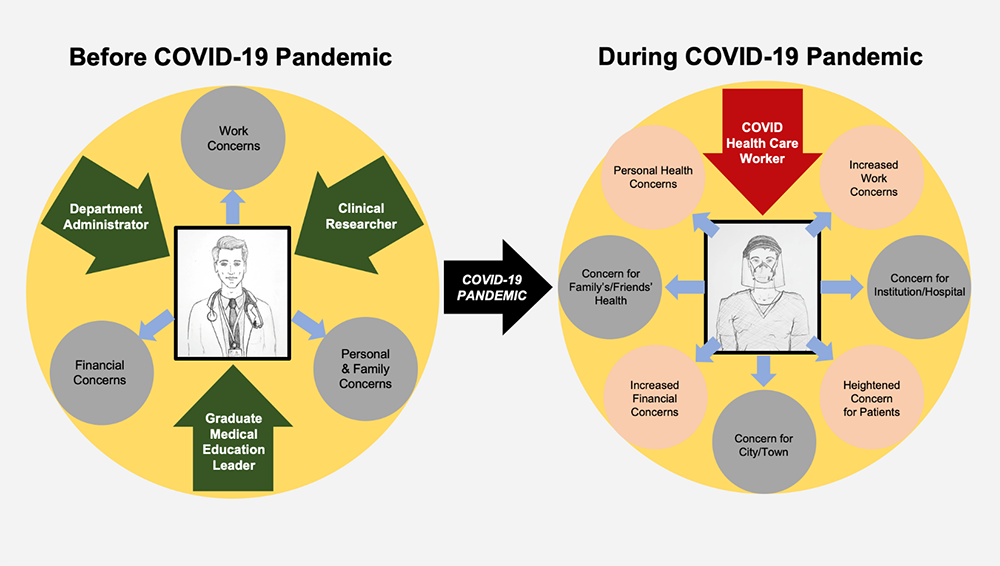

Figure 1: Experiences of Health Care Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic