How To of Emergency Action Planning

Quick Takes

- Understand the core principles of an emergency action plan.

- Describe the importance of CPR and AED training for all stakeholders in sport.

- Illustrate how sudden cardiac arrest can look in an athlete.

The Fundamentals of Emergency Action Planning

Introduction

Each year, it is estimated that 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 80,000 athletes will suffer sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) during or soon after athletic activity.1 Often these are highly publicized, visible, and scrutinized events. It is also well established that certain populations are at higher risk of these events than others. For instance, males of Black race who play basketball and/or football are at higher risk of SCA than other subpopulations.2-4 Prompt recognition of SCA, response with cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and application of an automated external defibrillator (AED) saves lives. Equally as important, though, is a well-planned, well-rehearsed emergency action plan (EAP). EAPs are recommended for every organization, school or institution that sponsors athletic activity.5

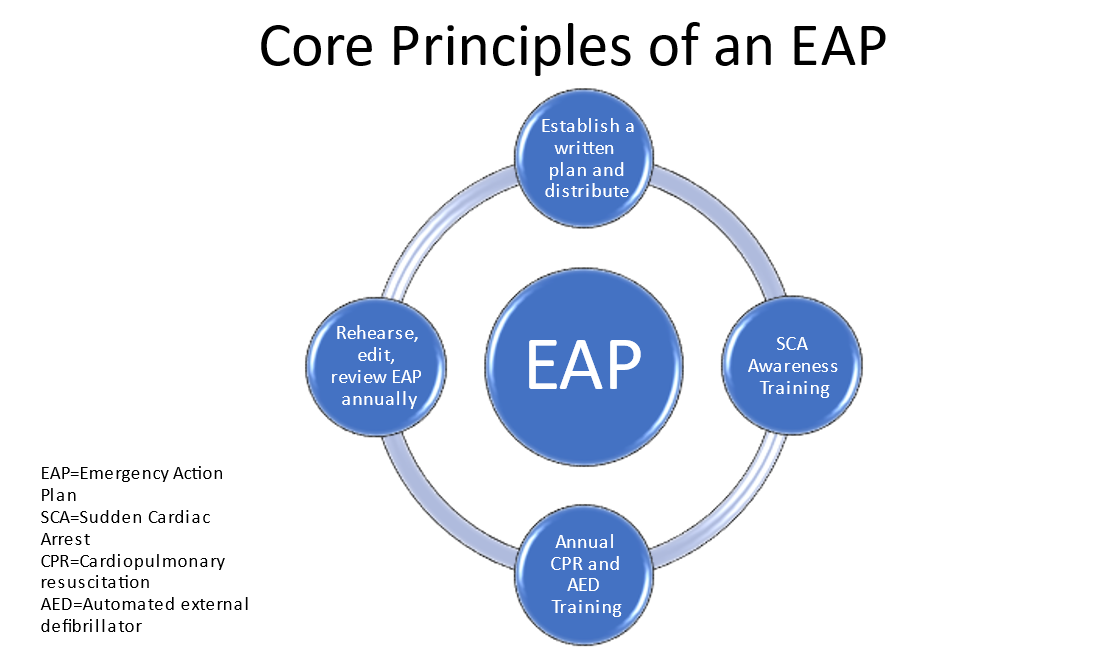

It is recognized that EAPs are best if holistic. A comprehensive EAP should include items such as mental health emergencies, concussion management, heat illness, and severe weather to name a few. While these are encouraged to be considered when developing the EAP, they are beyond the scope of this document. Below, we review the best practices of how to initiate and develop an EAP from the perspective of cardiac emergencies, specifically SCA. Figure 1 illustrates the key components of an EAP.

Figure 1: Core Principles of an EAP. Courtesy of Friedman EM.

Best Practices

- Establish an EAP coordinator. This person will lead the EAP's development, implementation and rehearsal. The EAP coordinator should be tasked with composing a document that houses the EAP. This document should be distributed to all stakeholders and displayed in a public setting for all to review. It should also be made available on days of formal competition (see number 8).

- Meet with all relevant stakeholders to ensure all are trained in CPR and AED use. It is imperative to identify who potential first responders are should SCA or another emergency arise during athletic activity. Stakeholders will include coaches, officials, medical directors, and athletic trainers. Members from local emergency medical services (EMS) should be involved at the initial stages of planning. Athletes themselves should be considered as first responders as well. In team-based sport especially, this provides a unique opportunity to serve as a first responder not only during athletic activity, but also during periods of general congregation and camaraderie off the field should a medical emergency occur. Media reports suggest that student athletes are appreciative and desire more of this type of training.6,7 It is important to ensure training in CPR and AED use is done by those who are certified trainers and that the training matches local requirements and mandates. Resources for this training can include local hospital systems, CPR/AED training facilities, or EMS providers.

- Train all first responders in how SCA looks during sport participation. Features which are unique to athletic activity include non-contact athlete collapse, unresponsiveness, and seizure-like activity. All of these should be presumed SCA until proven otherwise. A collapsed or unresponsive athlete should immediately prompt the initiation of Basic Life Support. The athlete should be checked for responsiveness, a pulse should be checked, and the chest should be examined for rise indicating spontaneous respiration. If all are absent or there is any doubt, CPR should commence, an AED should be obtained, and the EAP should be activated.

- Ensure AEDs are in accessible areas. Access to an AED should be reliable, accessible, and available to retrieve. Application and delivery of a shock must occur within 3 minutes of SCA recognition.8 Thus, it is imperative that all AEDs are kept in areas that are always accessible, well-marked, and regularly maintained as per manufacturer guidelines.

- Plan for situation and venue specific circumstances. SCA in an empty basketball gymnasium during practice or theatre during a dance rehearsal is quite different than the challenges posed by the same SCA event occurring during a game or performance in a crowded venue. A map should be created displaying the locations of all AEDs, access to the facility for EMS, and clear directions to the nearest medical facility.

- Identify the nearest accepting medical facility. Work with EMS and community members to identify a facility capable of advanced cardiac care. The chosen facility should be made aware of their involvement in the EAP and should work with the EAP coordinator and EMS on pre-hospital care following SCA at an athletic event.

- Rehearse and edit the EAP. The EAP should be rehearsed at least once per year with all stakeholders present. This rehearsal should serve as a time to review the plan and make any necessary edits.

- Review the EAP prior to any formal athletic competition. On competition days, a stakeholder from the venue's EAP committee should review the EAP with relevant officials, athletic trainers and others as needed. This serves as an important opportunity to mentally rehearse the EAP and plan for execution of the EAP should the need arise. This also is an opportunity for the visiting team or organization to disclose any relevant information they may have, which could impact the venue's EAP.

Final Thoughts

The EAP is an invaluable tool in the armamentarium of any venue that sponsors athletic or performance activity. As all athletes and performance artists are taught from a young age, practice makes perfect. CPR and AED training should be continually reinforced and offered to all members of a sporting organization (not just EAP stakeholders) and the EAP should be rehearsed and edited at least once per year. These fundamental efforts form the foundation for which lives can be saved should medical emergencies arise.

References

- Semsarian C, Sweeting J, Ackerman MJ. Sudden cardiac death in athletes. BMJ 2015;350:h1218.

- Maron BJ, Haas TS, Murphy CJ, Ahluwalia A, Rutten-Ramos S. Incidence and causes of sudden death in U.S. college athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1636-43.

- Harmon KG, Asif IM, Klossner D, Drezner JA. Incidence of sudden cardiac death in National Collegiate Athletic Association athletes. Circulation 2011;123:1594-600.

- Harmon KG, Asif IM, Maleszewski JJ, et al. Incidence, cause, and comparative frequency of sudden cardiac death in National Collegiate Athletic Association athletes: a decade in review. Circulation 2015;132:10-19.

- Siebert DM, Drezner JA. Sudden cardiac arrest on the field of play: turning tragedy into a survivable event. Neth Heart J 2018;26:115-19.

- DII SAAC receives certification in CPR, AED (NCAA website). 2016. Available at: https://www.ncaa.org/about/resources/media-center/news/dii-saac-receives-certification-cpr-aed . Accessed 07/30/2021.

- Foigel A, Garcia Austt S. Sharks Gain Valuable Sports-Focused CPR and AED Experience (NSUSharks website). 2019. Available at: https://nsusharks.com/news/2019/1/24/sharks-gain-valuable-cpr-and-aed-experience.aspx?path=general . Accessed 07/30/2021.

- Casa DJ, Almquist J, Anderson SA, et al. The inter-association task force for preventing sudden death in secondary school athletic programs: best practices recommendations. J Athl Train 2013;48:546-53.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Sports and Exercise Cardiology, Implantable Devices, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias

Keywords: Emergencies, Fitness Centers, Defibrillators, Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation, Death, Sudden, Cardiac, Emergency Medical Services, Athletes, Emergency Responders, Hospitals, Schools, Heat Stress Disorders, Respiration, Seizures, Sports

< Back to Listings