Health Care Policy and CHD – 2020 Focus on Our 2030 Future: Top 10 Things to Know

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common birth defect and the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children.1 It is a resource-intensive life-long disease with many associated comorbidities.2 Despite being only 3.7% of pediatric admissions, it accounts for 15% of all inpatient costs, estimated to be $5.6 billion in the United States (US) annually.3 In addition, this population is subjected to numerous public health issues, including increasing costs, healthcare disparity towards racial/ethnic subgroups, and non-transparency of data outcomes amongst various centers in the country.

The Advocacy Workgroup for the Adult Congenital and Pediatric Cardiology section of the American College of Cardiology (ACC) provides support and commentary for advocacy efforts in patients with CHD. The Workgroup notes current legislation and regulations for adult cardiology cannot be extrapolated to the pediatric population with its unique problems and needs. Advocacy efforts specific to pediatric patients with CHD require transparency and public reporting of patient outcomes. Quality improvement initiatives are imperative to make meaningful assessments of current practices and to develop strategies to improve them. All healthcare workers deserve opportunities for professional growth regardless of gender and race.

The following are key points to know regarding healthcare policy as it pertains to CHD:

- Value in Care: CHD is the most common congenital defect in children1 and is a resource-intensive lifelong disease.2 Regulations and legislations particularly related to CHD care need to be developed such that healthcare workers can tailor care to provide the highest value to patients with very specific and unique needs and focus on improving health related quality of life.4

- Value in Care: Recognition of "non-measurable" work is very important. Provider productivity, typically assessed through assigned weights in work relative value units (wRVUs) should objectively consider the time and effort spent and the skill required for such medical decision making.

- Excellence in Care: Assessing patient outcomes is an important step in quality improvement, therefore transparency and public reporting of CHD data, including patient outcomes, are essential.5 Registries and databases may enable collaborative knowledge sharing and improvement in quality of care.6

- Excellence in Care: Patient-family centered organizations are key players in advocating for the CHD population, identifying gaps in healthcare and developing solutions in collaboration with healthcare providers. They can also play an important role in creating awareness regarding the need for multidisciplinary and lifelong care, and prevention of CHD by appropriate screening and management of diseases such as gestational diabetes and maternal infections.7,8

- Excellence in Care: It is recommended that patients with complex cardiac diseases and those with multiple, difficult to manage associated comorbidities receive care at specialized cardiac centers, where coordinated, multidisciplinary care may be achieved. It is also important to ensure that patients are appropriately transitioned and transferred to adult CHD care when appropriate.9,10

- Community Diversity and Disparities: The CHD community faces many public health issues such as disparities and inequity in care towards racial and ethnic groups, increasing healthcare costs, and challenges with transparency of CHD data across centers. These all have become more evident during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Community Diversity and Disparities: Delivery of care affected by systemic racism needs to be addressed and policies need to be put in place to improve outcomes of the population belonging to vulnerable ethnicities. This can be achieved by expansion of Medicaid coverage.11

- Workforce – Administrative Burden: 'Patient over paperwork' should be adopted by healthcare systems to overcome unnecessary delays in care and added costs. Legislations and regulations are necessary to limit prior authorization and the delays associated with it.

- Workforce – Infrastructure: Obtaining, analyzing, and reporting workforce data in pediatric and adult congenital cardiology is important. Pediatric cardiology is a competitive subspecialty. Despite an increase in fellowship training programs, the number of applicants exceeds available positions.12 This warrants increased funding for more training positions and expansion of workforce opportunities.

- Workforce – Diversity and Disparities: Significant gender and racial disparities are evident in pediatric cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery. In 2016, only 34% of the cardiac workforce consisted of women, 9.9% of the pediatric cardiology fellows, and 7.8% belonged to the underrepresented minorities.13 Studies have shown that increased diversity leads to improved critical thinking and improved scientific research output. Policies should be set in place to ensure equity among the workforce, including leadership positions.14

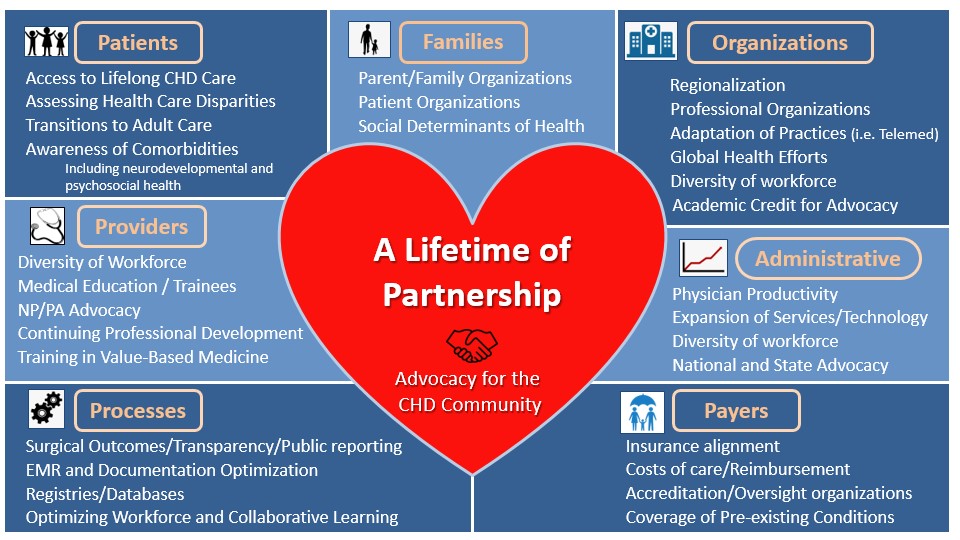

Figure 1

References

- GBD 2017 Congenital Heart Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of congenital heart disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020;4:185–200.

- Pasquali SK, Thibault D, O'Brien SM, et al. National variation in congenital heart surgery outcomes. Circulation 2020;142:1351–60.

- Simeone RM, Oster ME, Cassell CH, Armour BS, Gray DT, Honein MA. Pediatric inpatient hospital resource use for congenital heart defects. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2014;100:934-43.

- Abassi H, Huguet H, Picot MC, et al. Health‐related quality of life in children with congenital heart disease aged 5 to 7 years: a multicentre controlled cross‐sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2020;18:366.

- Patel A, Gandhi R. An ethical argument for professional regulation and regionalization of care in pediatric cardiology and cardiac surgery. Pediatr Cardiol 2020;41:651–53.

- McHugh KE, Mahle WT, Hall MA, et al. Hospital costs related to early extubation after infant cardiac surgery.Ann Thorac Surg 2019;107:1421–26.

- Jenkins KJ, Botto LD, Correa A, et al. Public health approach to improve outcomes for congenital heart disease across the life span. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e009450.

- Congenital Heart Defects (aap.org). 2022. Available at: http://www.chphc.org. Accessed 07/26/2021.

- Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:1494-1563.

- Everitt IK, Gerardin JF, Rodriguez FH, Book WM. Improving the quality of transition and transfer of care in young adults with congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis 2017;12:242–50.

- Sanders SR, Cope MR, Park PN, Jeffery W, Jackson JE. Infants without health insurance: racial/ethnic and rural/urban disparities in infant households' insurance coverage. PLoS One 2020;15:e0222387.

- National Resident Matching Program. NRMP Program Results 2004–2008 Specialties Matching Service® (nrmp.org). 2020. Available at: https://www.nrmp.org/match-data-analytics/archives/. Accessed 07/26/2021.

- Mehta LS, Fisher K, Rzeszut AK, et al. Current demographic status of cardiologists in the United States. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:1029-33.

- Terlizzi EP, Connor EM, Zelaya CE, Ji AM, Bakos AD. Reported importance and access to health care providers who understand or share cultural characteristics with their patients among adults, by race and ethnicity. Natl Health Stat Report 2019;130:1–12.

Clinical Topics: Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, COVID-19 Hub, Congenital Heart Disease, CHD and Pediatrics and Prevention, CHD and Pediatrics and Quality Improvement

Keywords: Healthcare Disparities, Public Health, Inpatients, Quality Improvement, Heart Defects, Congenital, Health Personnel, Health Policy, Morbidity, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Diabetes, Gestational, Ethnic Groups, Leadership, Medicaid, Pandemics, Prior Authorization, Quality of Life, Clinical Decision-Making, Delivery of Health Care, Heart Diseases, Health Care Costs, Registries

< Back to Listings