Focus on Heart Failure | Weight Loss Pharmacotherapy For Obesity-Phenotype HF: The Greatest Thing Since Sliced Bread?

The burdensome convergence of two rapidly growing epidemics, namely obesity and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), cannot be overstated. Currently in the U.S., one in five high school students has obesity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Meanwhile, most patients with HFpEF have obesity, with approximately 80% measuring as either overweight or obese by traditional body mass index (BMI) cutoffs.

I see many patients with obesity-phenotype HFpEF when I drive two hours northeast of Kansas City to an outreach clinic in Chillicothe, MO – the rural farming community officially recognized as the "home of sliced bread" (the home of the Rohwedder Bread Slicer, invented and put into first use there in 1928). The typical patient with HFpEF often comes with no formal diagnosis of HF situated on the problem list.

HF and Obesity in Practice: The Case of Mrs. Jones

A case in point is "Mrs. Jones," a 65-year-old woman who sees me for "shortness of air" as her listed reason for her visit. Meanwhile, her problem list includes the usual cast of characters: paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AFib) status post ablation, essential hypertension, dyslipidemia, and (there it is at the bottom) obesity.

I note there is no diagnosis or reference to HF anywhere in her chart, yet she sees me (a HF specialist) and immediately wants to know if she is going to die of HF in the next five years (after Googling me on the internet and reading my X posts). She is on flecainide, a hefty dose of carvedilol, niacin and rivaroxaban, along with amlodipine which she believes has made her ankle swelling worse this summer.

She tells me she struggles with gardening lately and keeping up with grandkids on her farm, and her husband "Roy" wants to know why she's huffing and puffing around the kitchen.

When she reclines to 30 degrees of elevation on the examining table, I notice the readily visible jugular vein pulsations, and I document 9 cm of water along with "augmented P2 compared to A2" in the EMR. I don't obsess over her pitting edema to the shins, but I do note the brawny tree-bark appearance of her skin that seems to have developed over a decade.

I pull up her echocardiogram in the office to review images with her after noting left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy and a few atrial premature beats on her 12-lead ECG along with the BNP of 85 on labs from six months ago. She had been told her ECG, echocardiogram and labs were "normal" and inconsistent with HF.

I note her E/e' is 16 and her estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure is 40 mm Hg but with an LV ejection fraction of 55%. I later check a C-peptide which comes back at 8 (suggesting some insulin resistance), and I screen her urine for albuminuria. The urine albumin-creatinine ratio comes back as 35 with a hemoglobin A1c of 6.4%. Her comprehensive metabolic profile also demonstrates some low-grade "transaminitis" along with mild anemia and thrombocytopenia.

Mrs. Jones looks like the typical patient with obesity-phenotype HFpEF. To be fair to other clinicians who saw Mrs. Jones, many of the usual therapies were offered. She was told to lose weight. But we know that for patients with HFpEF and obesity, a maximum of 10% body weight reduction can be achieved through both diet and exercise (in the structured and supervised clinical trial setting) but quality of life remains markedly impaired.

Yes, her AFib is under better control with aggressive strategies, but in many ways, she sees these interventions as "window-dressing" because she has experienced relapses back to fibrillation requiring cardioversion. The higher dose of carvedilol, she notes, really "holds her back," and she is "exhausted" nearly continuously.

Her BNP of 85 in the context of her BMI of 37 leads many a clinician to falsely reassure Mrs. Jones with, "no worries here, the diagnosis is not heart failure, it's just your weight." But we have observed repeatedly the inverse relationship between natriuretic peptide levels and BMI.

In fact, many patients who lose weight after decongestive therapies like diuretics will be observed to have natriuretic peptide levels rise, leading to more confusion about how such a patient is doing on therapies for HFpEF.

When I review with her starting an SGLT2 inhibitor, as is now endorsed by society guidelines as recommended therapy,1,2 she states, "You know, I was on that Jardiance, but it was stopped after another doctor saw my creatinine went up a little after starting it."

She notes feeling "a bit better" on the SGLT2 inhibitor when she was on it, which is consistent with the modest but clinically meaningful benefit observed in the EMPEROR-Preserved, DELIVER and PRESERVED-HF trials.

Obesity as a Driver of HF

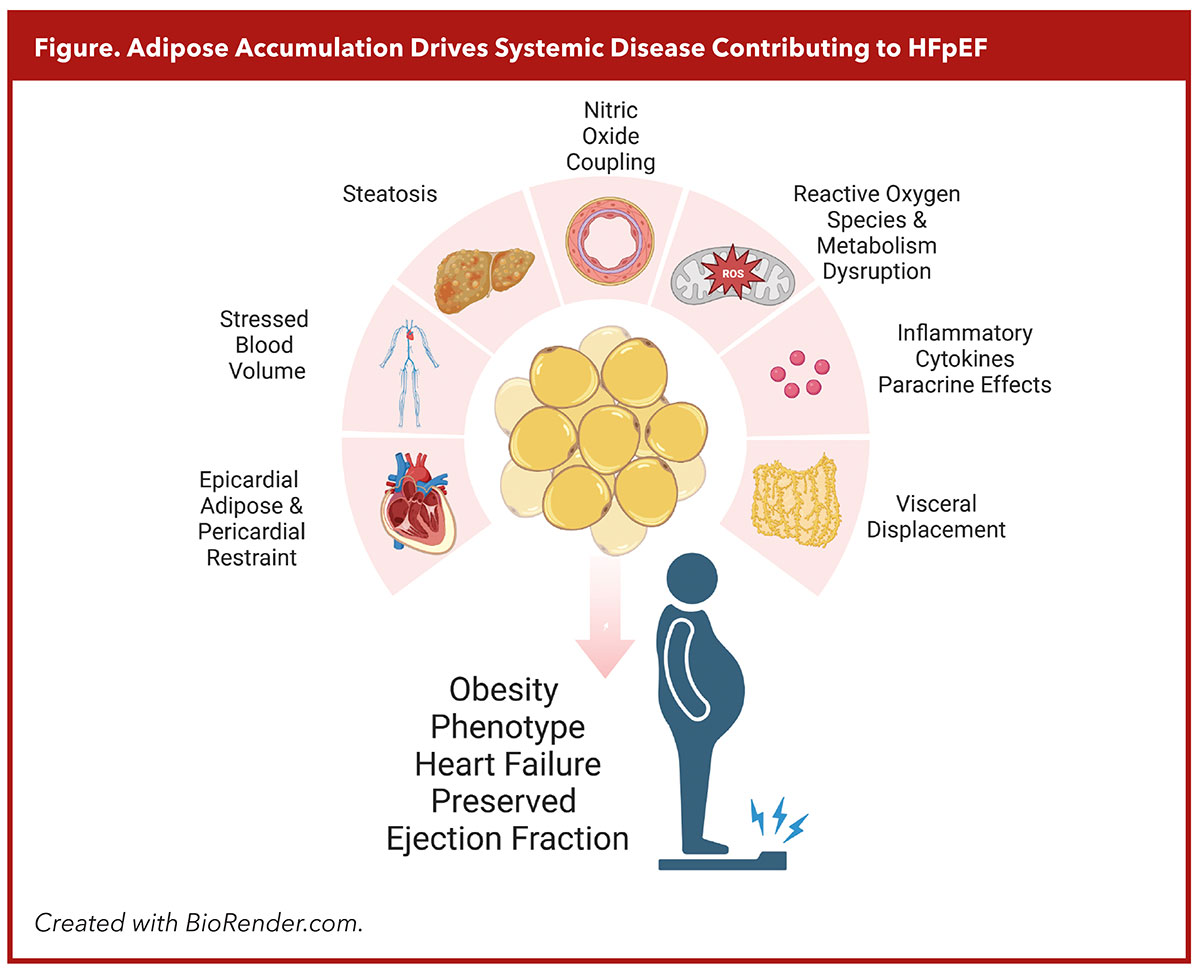

Many of our colleagues have described 2023 as the year our community took steps to pharmacologically target obesity itself as an etiological driver of HFpEF, not just as a comorbid condition. And this makes sense when considering the relationship between adipose accumulation and the resulting systemic disease contributing to HFpEF pathophysiology (Figure).

Adipose depots impact variably on surrounding tissue with cytokine release coinciding with local paracrine and vasocrine effects, perturbing nitric oxide coupling and expanding reactive oxygen species which contribute to microvascular injury, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, myocardial fibrosis and adverse remodeling promoting diastolic dysfunction.3

Visceral fat is among the most potent risk factors for developing HFpEF and is associated with mechanical disruption of splanchnic circulation, venoconstriction, decreased systemic vascular resistance, steatosis, increased aldosterone levels, hypertension and increased stressed blood volume.

Intermuscular adipose deposition contributes to insulin resistance, mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired oxygen uptake during exercise, all of which contribute to the hallmarks of obesity phenotype HFpEF. Epicardial adipose tissue creates mechanical disruptions to exercise hemodynamics by restricting end diastolic volume during exercise while also mediating deleterious effects on the myocardium through local cytokines.

Although diet-driven weight loss improves exercise capacity and health status in the HFpEF obesity phenotype, caloric restriction (caused by food or medications) results in approximately 30% of weight loss due to loss of skeletal muscle mass. Lean body mass loss is an issue in HFpEF patients, who also suffer from frailty and sarcopenia.

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Step Up to the Plate

Glucogon-like-peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) and other incretin-based therapies enter the picture as GLP-1 agonism exerts several observed favorable pleiotropic effects on glucose metabolism, insulin sensitivity, gut motility, appetite, lipolysis, steatosis, natriuresis and inflammation.

The 2021 prelude presentation of the STEP1 trial examined semaglutide weekly in adults with overweight BMI plus a comorbidity or with obesity and no comorbid condition. Patients randomized to escalated dose of semaglutide 2.4 mg once weekly experienced a mean 14.9% weight decline; notably 86% with at least 5% and 32% with at least 20% weight loss, respectively. Gastrointestinal or hepatobiliary side effects were the most common adverse events leading to discontinuation of study drug in 7% of patients randomized to semaglutide (compared with 3% randomized to placebo).4

As the first late-breaking clinical trial presented at the 2023 ESC Congress, Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, FACC, presented the initial results of STEP-HFpEF, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted at 96 sites globally, randomizing 529 people with obesity-phenotype HFpEF and without diabetes (56.1% women, median age 69 years) to semaglutide 2.4 mg vs. placebo weekly injection for 52 weeks.5

With a median BMI of 37 kg/m2 and particularly deranged health status and exercise function at baseline (assessed by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire [KCCQ] and six-minute hall-walk distance [6MWD], respectively], these patients had substantial HF-related symptoms and physical limitations consistent with obesity-phenotype.

Dual primary endpoints were the change in KCCQ clinical summary score (KCCQ-CSS) and in body weight. STEP-HFpEF met both primary endpoints with a mean change in KCCQ-CSS of 16.6 points with semaglutide 2.4 mg vs. 8.7 points with placebo. Body weight proportion loss was 13.3% with semaglutide (notably like that seen in the STEP1 trial), compared with only 2.6% weight loss with placebo. The nearly 8-point comparative improvement in KCCQ-CSS on semaglutide vs. placebo was the most marked we have seen for any study of patients with HFpEF.

Participants randomized to the GLP-1 RA also walked 21.5 meters farther on average after losing weight, compared with 1.2 meters among those treated with placebo. Only the PRESERVED-HF trial has demonstrated similar improvement in 6MWD for patients with HFpEF.

Finally, natriuretic peptide levels and inflammatory markers were significantly reduced among patients treated with semaglutide, compared with those on placebo, supporting the hypothesis that GLP-1 receptor agonism can help address congestion and inflammation at the center of the disease.

Obesity as a Systemic Illness

Lead investigator Kosiborod reflected on the obesity-phenotype HFpEF and the implications of STEP-HFpEF in the Intention to Treat podcast from the New England Journal of Medicine, saying:

"We've been so conditioned, as cardiologists, to kind of think, when we see a patient with [HF], to see and think about the heart [as] being the primary cause of the problem that it hasn't occurred to us, as much as it should have, that in fact obesity is a systemic disease that affects multiple organ systems, and [the] heart is just one of them… Even though the heart function is preserved, it hasn't occurred to us that this is actually just one of the manifestations of the systemic disease which is obesity. It's not an accident that [the] majority of patients with this type of [HF] have obesity. Obesity is in fact causing it. That realization has not really occurred until now. You could argue that it should have, but it hasn't."

In the same podcast, a patient with lived experience who was treated with semaglutide as a patient in the STEP-HFpEF trial, poignantly captured the patient's side of the story for the consideration of our community of patients and clinicians facing the obesity and HFpEF epidemic. She reflected:

"I think our country needs to realize that we have a huge weight problem, and we need help with that. We understand smoking is a problem. Alcoholism is a problem. It seems to be that if you're overweight, that's just your fault. We need help in realizing that obesity is an illness too, like all other illnesses, that we need support in that, from our doctors and our insurance companies."

For the love of sliced bread, and for my own patient Mrs. Jones, I hope we truly are witnessing the paradigm shift the scientific and clinical community has been buzzing about in 2023. Will we cardiologists take up the role of treating bread-loving patients with obesity? If we agree to this challenge, how will these medications be covered?

We could at least work to participate together in the subsequent studies necessary to solidify obesity as a distinct cause of HFpEF and to appraise the most safe and effective weight-loss therapies, steadily advancing our collective aim to improve quality and quantity of life for our patients while reducing many comorbid complications of the disease.

This article was authored by Andrew J. Sauer, MD, associate director, Cardiovascular Research, and associate professor of medicine, Department of Cardiology at Saint Luke's Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, MO.

References

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:e263-e421.

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2023 focused update of the 2021 ESC guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2023;44:3267-3639.

- Antoniades C, Tousoulis D, Vavlukis M, et al. Perivascular adipose tissue as a source of therapeutic targets and clinical biomarkers. Eur Heart J 2023;44:3827-44.

- Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med 2021;384:989-1002.

- Kosiborod MN, Abildstrøm SZ, Borlaug BA, et al. Semaglutide in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and obesity. N Engl J Med 2023;389:1069-84.

Clinical Topics: Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Prevention, Acute Heart Failure, Diet

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Heart Failure, Diuretics, Blood Pressure, Pulmonary Artery, Obesity, Diet

< Back to Listings