Peripheral Matters | Carotid Artery Stent NCD Expansion: Implications For Management of Atherosclerotic Bifurcation Carotid Disease

The first carotid stent system achieved approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for high-surgical risk patients in 2004.1

Within the next year, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a highly restrictive National Coverage Decision (NCD), which limited the use of transfemoral carotid artery stenting (TF-CAS) only to recently symptomatic patients with high-surgical risk features – about 10% of the total at-risk carotid population.

CMS had the opportunity to modify this decision three more times in as many years, based on a growing, increasingly favorable, and large set of prospective national data from high quality, postmarket registries and several more pivotal device approval trials, but chose not to.

In the following decade, voluminous (>8,000 participants) prospective data were developed in large high-quality randomized controlled trials,2-5 all of which concluded that in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients at standard surgical risk, TF-CAS was noninferior to the standard of care of carotid endarterectomy (CEA).

Armed with these data, and in cooperation with the Coverage and Analysis Group at CMS, the Multispecialty Carotid Alliance (MSCA), a collection of leaders from multiple medical, neurological and surgical disciplines, formally requested a reconsideration of the NCD in late 2022.

On Oct. 11, 2023, CMS issued a revised NCD which lifted restrictions on the performance of TF-CAS, making it on par with CEA coverage and opening access to this technology as a realistic option unencumbered by insurance coverage for thousands of patients facing decisions on the management of a significant carotid stenosis.

Data Build the Case For TF-CAS

Much like the dog that finally catches the car after a good chase, the question is "now what?" It has been more than a decade – and practically a generation of cardiac interventionalists who have never even seen a TF-CAS procedure – since there has been a substantial practice of TF-CAS associated with trials and postmarket registries.

Moreover, in the intervening years, the world of carotid disease management has changed: transcarotid artery stenting (TCAR) emerged in 2017 as an alternative to CEA and has been embraced by vascular surgery – at last count more than 75,000 TCAR procedural outcomes have been entered into the Vascular Quality Initiative registry, primarily as a replacement for CEA.

The neurointerventional community, now widely involved with acute stroke intervention (not part of the landscape 10 years ago) is a relatively new entrant in TF-CAS by virtue of incidental or causative carotid disease associated with acute stroke. Medical therapy has continued to improve cardiovascular outcomes.

Accordingly, the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy vs. Stenting-2 (CREST-2) study, sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, has nearly completed its almost 2,500 participant randomization between intensive medical therapy with or without revascularization (either CEA or CAS) in asymptomatic standard surgical risk patients with severe carotid stenosis. This will hopefully – and finally – shed light on the comparative efficacies of these two strategies and the role of revascularization in the "modern" medical era.

Notably, although there had been a dearth of investment in new technologies for TF-CAS given the lack of a covered and reimbursed market to justify the spend, there are two exciting new technologies that have completed pivotal trials and reported data.

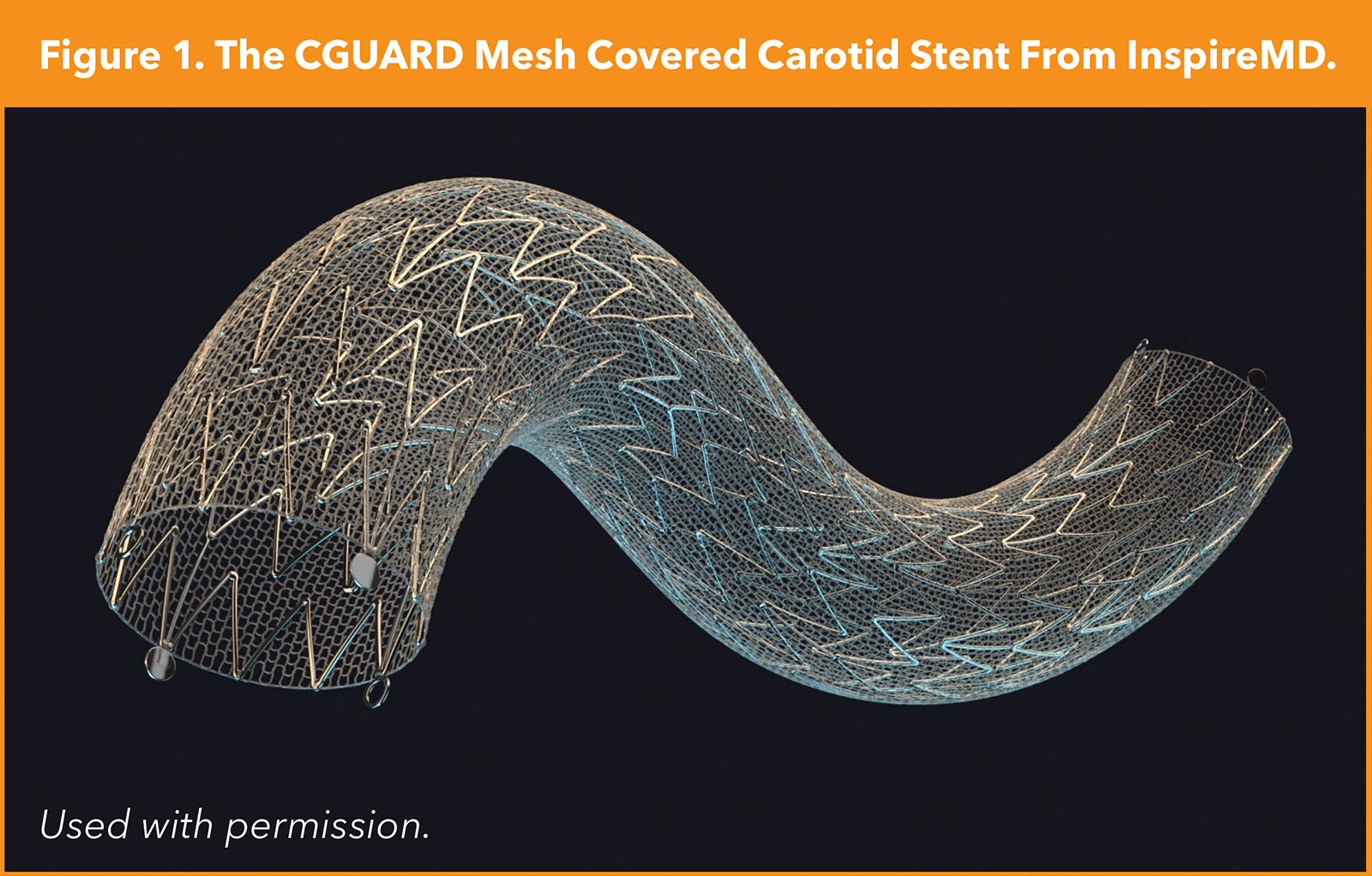

The C-GUARDIANS study examined the outcomes of the CGuard mesh-covered stent (InspireMD, Tel Aviv, Israel) – intended to limit/eliminate plaque protrusion as a source of late stroke postprocedure – in roughly 300 high-surgical risk patients, with 30-day outcomes demonstrating very low rates of stroke, approximately 1%, with primary one-year endpoint data pending, according to data presented by Metzger, et al., at VIVA 2023 (Figure 1).

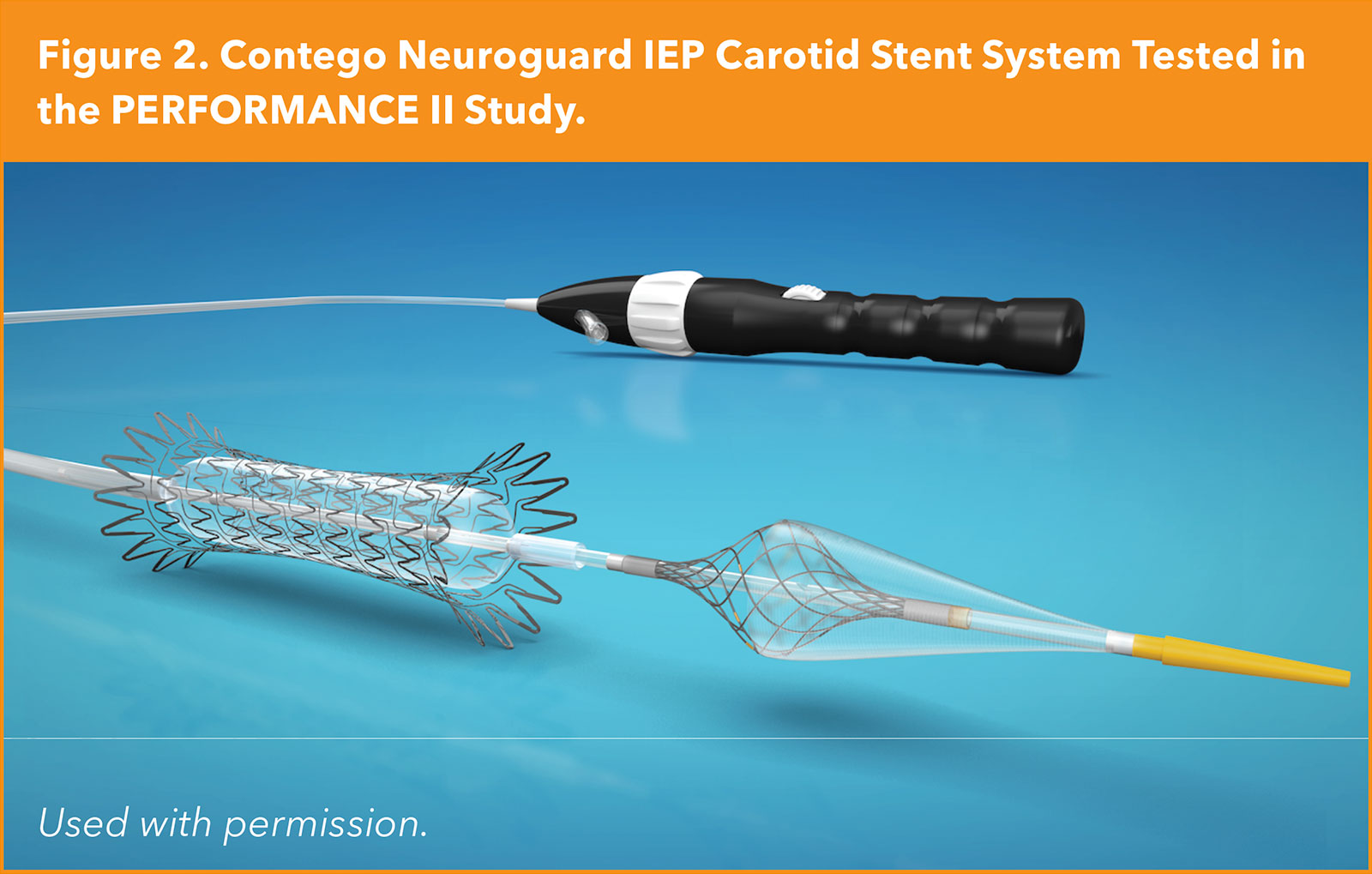

At the same meeting, the one-year primary endpoint data from the PERFORMANCE II trial were reported by Gray, et al. This study with approximately 300 participants examined the safety and effectiveness of the Neuroguard 3-in-1 carotid stent system (Contego Medical, Raleigh, NC) comprised of a handle-actuated filter with 40-micron pores (approximately one-third the pore size of standard carotid filters) attached to the distal end of the device, a purpose-built closed-cell nitinol stent (which nevertheless maintains flexibility), and a postdilation balloon. This system is used in conjunction with a standard distal filter.

At 30 days, the rate of stroke was approximately 1% and all were minor strokes. At one year, there was one additional unrelated stroke (with a patent stent) and no clinically driven target lesion revascularization, demonstrating both highly effective stroke prevention and durability of the stent.

Taken together, the procedural safety profile of these next-generation system study results is remarkable, and on par with other widely accepted stroke prevention procedures such as patent foramen ovale closure and left atrial appendage closure. If these trends bear out in larger experiences, there is no reason that TF-CAS could not be a first option for the carotid patient in the future.

Building the Workforce For TF-CAS

Although the future for TF-CAS appears bright given these various coverage and technology developments, the lack of a "workforce" must be judiciously addressed. Broadly, there will likely be three groups of physicians who will be interested in performing TF-CAS.

First will be those operators (e.g., cardiologists, radiologists and vascular surgeons) who had a carotid practice before loss of access to TF-CAS occurred (postmarket studies became completed, etc.). Second will be vascular surgeons who had/have not acquired the requisite skills but now will want to complement their CEA (and possibly TCAR) offerings. And third will be the new nonsurgical operator interested in adding TF-CAS to their practice to service their patients.

Educational and training efforts, therefore, will need to be customized to the trainee. The new operator will need training on the interpretation of various carotid imaging results (Duplex, CTA, MRA, angiography); the natural history of carotid disease treated medically; the outcomes and risks associated with all forms of revascularization (even if they don't perform them); patient selection (perhaps the most important aspect of achieving good outcomes); the diagnostic and interventional catheter tool set; carotid angiography and cerebral anatomy; complication avoidance and management such as carotid body-mediated bradycardia and hypotension; emboli causing significant neurological impairment; cath lab staff training; and more (Figure 2).

A new vascular surgical entrant will not need the same training in the cognitive aspects but will likely need much of the same procedural elements, and may need more work with 0.014" wires and catheters, cerebrovascular vessel access from the femoral (or radial) access point, etc. Thus, customizable training relevant to the background skills and experience of the operator will be key.

Happily, simulation models have progressed significantly since the first "wave" of carotid stent training 15-20 years ago and can be extremely useful (but cannot replace) adjuncts to the necessary didactic course work. And in certain instances involving novice operators, the addition of a physician proctorship will be an important final component of assuring optimized clinical outcomes.

The Road Ahead

As can be seen from the foregoing, an incredible amount of work has been done by innumerable individuals: engineers; industry and governmental sponsors; internal review boards; investigators; clinical-regulatory agencies (FDA) and staff; CMS; and physician societies, to name just a few. We especially must remember all the participants who volunteered to be in clinical trials with unknown outcomes, oftentimes as an altruistic act in hopes of advancing medicine for future patients.

To do justice to what has come before, it is therefore incumbent on all of us in this field to take seriously the goal of optimizing the outcomes for patients with atherosclerotic bifurcation carotid stenosis. This means making certain that we are well trained and prepared, that we select patients who are at low risk for TF-CAS (e.g., good aortic arch anatomy, limited access vessel tortuosity, discrete and not heavily calcified carotid lesions, etc.), especially in light of the presence of other excellent revascularization choices.

Importantly, most of us will not be able offer the full gamut of revascularization options and therefore must be willing to refer to those operators who are expert in the alternatives. It is only with the complementary – not competitive – use of medical therapy, CEA, CAS and TCAR that we will achieve the lowest rates of mortality and stroke (with its associated disability) and maximize the benefits for our patients and their families.

This article was authored by William A. Gray, MD, FACC, system chief, Cardiovascular Division, Main Line Health; professor of medicine, Sidney Kimmel School of Medicine at Thomas Jefferson University; Phillip D. Robinson Endowed Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine, all in Philadelphia; and co-director, Lankenau Heart Institute in Wynnewood, PA; and Kenneth Rosenfield, MD, MHCDS, FACC, section head, Vascular Medicine and Intervention, Division of Cardiology, Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

References

- Gray WA, Hopkins LN, Yadav S; ARCHeR Trial Collaborators. Protected carotid stenting in high-surgical-risk patients: the ARCHeR results. J Vasc Surg 2006;44:258-68.

- Brott TG, Hobson RW 2nd, Howard G; CREST Investigators. Stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of carotid-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2010;363:11-23.

- Rosenfield K, Matsumura JS, Chaturvedi S; ACT I Investigators. Randomized trial of stent versus surgery for asymptomatic carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1011-20.

- Halliday A, Bulbulia R, Bonati LH; ACST-2 Collaborative Group. Second asymptomatic carotid surgery trial (ACST-2): A randomised comparison of carotid artery stenting versus carotid endarterectomy. Lancet 2021;398:1065-73.

- Reiff T, Eckstein HH, Mansmann U; SPACE-2 Investigators. Carotid endarterectomy or stenting or best medical treatment alone for moderate-to-severe asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis: 5-year results of a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2022;21:877-88.

Clinical Topics: Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Vascular Medicine, Interventions and Vascular Medicine

Keywords: Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications, Endarterectomy, Carotid, Carotid Stenosis, Atrial Appendage, Disease Management, Device Approval