Focus on Heart Failure | Heart Failure in Women: Understanding the Differences to Change the Paradigm

Every February, American Heart Month affords the cardiology community the opportunity to reflect on how we promote cardiovascular health and educate the public and our patients. It's also an opportunity to take stock of disparities and redouble our efforts to provide more equitable care.

Many of us may be surprised to be reminded that, despite many campaigns, awareness that heart disease is the leading cause of death among women declined from 2009 to 2019, particularly among Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black women and in younger women.1

One can only expect that their awareness about the risk of heart failure (HF) is even less prevalent.

Notably, the incidence of HF is increasing more in women than in men, especially among racial and ethnic minorities. Furthermore, there are striking sex differences related to epidemiology, risk factors, clinical manifestation and outcomes of HF in women.2,3

Women are less likely to receive evidence-based HF therapies, and experience delays in referral for and access to advanced HF therapies.4,5 Despite these differences, women are underrepresented in HF clinical trials, accounting for approximately 20-25% of study participants, impeding the development of evidence-based, sex-specific therapeutic approaches.

Pathophysiologic Sex Differences in HF

Depending on the underlying type of HF the patient may experience, there are several pathophysiologic differences which place women at higher risk for certain types. Women have demonstrated a greater predisposition to endothelial inflammation and coronary microvasculature dysfunction.6 At the cellular level, endothelial inflammation is characterized by altered nitric oxide signaling.7

There are also sex differences in the immune response in general, with women generally exhibiting greater pro-inflammatory cytokines, activation of inflammatory T cells, heightened inflammation with greater levels of inflammatory markers, and in female myocardium an upregulation of pro-inflammatory gene expression.8

Women are at higher risk of HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) than men and this is related to several sex differences. Endothelial dysfunction of both the systemic and pulmonary vasculature may play a role in the pathophysiology of HFpEF. Women have a higher predisposition to age-associated ventricular-arterial uncoupling and impaired ventriculo-vascular coupling with blunted exercise coupling reserve, which is a fundamental abnormality in HFpEF.9

Prior imaging studies have shown women, compared with men, with HFpEF were more likely to have concentric left ventricular (LV) remodeling, more severe diastolic dysfunction including more impaired LV relaxation and higher diastolic stiffness, and higher LV filling pressures.10

During prior invasive studies, women had higher pulmonary capillary wedge pressure adjusted to workload, greater LV end-systolic and diastolic elastance, and higher LV filling pressures both at rest and peak exercise than men.11 Overall, women present with nonischemic heart failure etiologies, whereas men have more ischemic disease.

In regard to hormones, it remains not well understood why estrogen may be relatively protective in the development of various cardiovascular diseases, yet supplemental estrogen can increase the risk in some disease states.12

In regard to HF specifically, there is evidence of a relationship between sex hormones and cardiac hormones, namely natriuretic peptides, where high testosterone (in men and postmenopausal women) may lower natriuretic peptides and predispose to the natriuretic peptide deficient state of HF.13

Sex-Specific Risk Factors in HF

Engaging Patients With HF

Looking to better facilitate conversations with your patients and involve them in their care? Click here to access CardioSmart's HF topic collection and all the related tools, including infographics, action plans, decision aids, fact sheets and more.

There are important sex differences in both traditional cardiovascular risk factors and sex-specific risk factors. Obesity is more prevalent in women than men and is a greater risk factor for HF in women with increased tendency for HFpEF.14 Diabetes is a more prominent risk factor for HF in women. Women with diabetes have greater signs of adverse LV remodeling, increased LV wall thickness and LV mass index.15

While the prevalence of hypertension is similar between women and men, women with hypertension have a higher risk of developing HF than men (threefold vs. twofold, respectively).16 Women have a lower incidence of tobacco use, but association of smoking with HF in women is almost double that of men (88% vs. 45%).17 Socioeconomic status, especially income disparities among the sexes, has been associated with worse HF outcomes in women.18

Childbearing is unique to women and pregnancy comes with particular risks, as it is a high-stress state with large changes in cardiovascular physiology that may exacerbate or unmask adverse pregnancy outcomes including gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia/eclampsia and peripartum cardiomyopathy. Peripartum cardiomyopathy can be a life-threatening condition that can present in the later stages of pregnancy through the first several months postpartum with an increasing incidence secondary to advancing maternal age, increased multiparity pregnancies, and earlier recognition.19

With breast cancer being the most common cancer in women, and women living longer with this disease with advancements in treatment options, some epidemiologic studies in breast cancer survivors have shown cardiovascular mortality exceeding cancer mortality.20

Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy occurs in about 10% of patients on standard doses of this drug and trastuzumab has cardiotoxic side effects in about 13% of patients receiving this drug.21 Radiation therapy has been implicated in risk for valvular cardiomyopathy, ischemic cardiomyopathy and HFpEF.

Certain types of autoimmune disease like systemic lupus erythematous have been linked to risk of cardiomyopathy and development of HF, and women have a higher prevalence of lupus compared with men.

Sex Differences in HF Therapies

Learn More on Online!

ACC Online Courses are an easy, free way to stay current on the latest science and guidelines at your own pace. Click here to access three different HF-related courses and learn more about CRT, SGLT2 inhibitors and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Women and men have different pharmacological responses to some medications, which impacts their treatment of HF. Women have been shown to have up to 2.5-times higher plasma concentrations of some HF medications, including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and beta-blockers.22 Such higher plasma concentrations can impact the dose response and often leads to an exacerbated side effect profile at doses similar with those used in men.

The risk of side effects is often underestimated for women based on results from clinical trials of HF drugs, in which men are more likely than women to be enrolled. In the PARAGON-HF trial, in which women were enrolled at an increased rate, sacubitril/valsartan was shown to reduce the likelihood of cardiovascular death and total hospitalizations more in women than men with HFpEF.23

While the TOPCAT trial was not a positive one, a subgroup analysis showed that spironolactone was associated with a lower all-cause mortality in women than men in the Americas.24

When it comes to device therapies for HF, women are less likely to receive an ICD than men.25 Some large meta-analyses of ICD trials have shown no benefit in women and fewer appropriate antitachycardia pacing therapies and ICD shocks in women. Women have less ischemic cardiomyopathy than men, which could account for less ventricular arrhythmias that typically benefit from ICD therapies. As opposed to ICDs, women are more likely to respond to CRT than men with better gains in mortality, improvement in LV ejection fraction and overall quality of life.26

Women can often have mitral regurgitation secondary to LV remodeling in HFrEF similar to men, but women are frequently referred for intervention later than men, which can lead to more need for replacement than repair, worse prognosis and more adverse remodeling post intervention.27

Sex Differences in Advanced HF Therapies

Advanced HF therapies such as durable left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) and heart transplantation improve survival in end-stage HF. In a multicenter retrospective analysis of referral patterns to nine advanced HF centers in the U.S., only 26.6% of referrals were women.28

Data from the MOMENTUM 3 study demonstrated no differences in the primary composite endpoint of survival free of disabling stroke or reoperation to replace or remove a malfunctioning pump or overall survival in women who received an LVAD, compared with men, at two years of support.

Women ≤65 years old suffered an increased burden of adverse events, including strokes, gastrointestinal bleeding and major infections, suggesting there is an increased need for research to better understand the reason for these sex differences and to elucidate the impact of tailored management particularly in younger women to mitigate these differences.4

Women account for only about 25% of heart transplant recipients in the U.S., due to a combination of lower referral, concerns with allosensitization, lower use of temporary mechanical circulatory support and increased waitlist mortality at the higher status levels. Women who do receive a heart transplant against these odds, have similar survival to male heart transplant recipients but with increased morbidity particularly regarding graft rejection, again signifying the need for sex-specific studies in post-transplant management.5

Balancing the Scales in Sex Disparities in HF

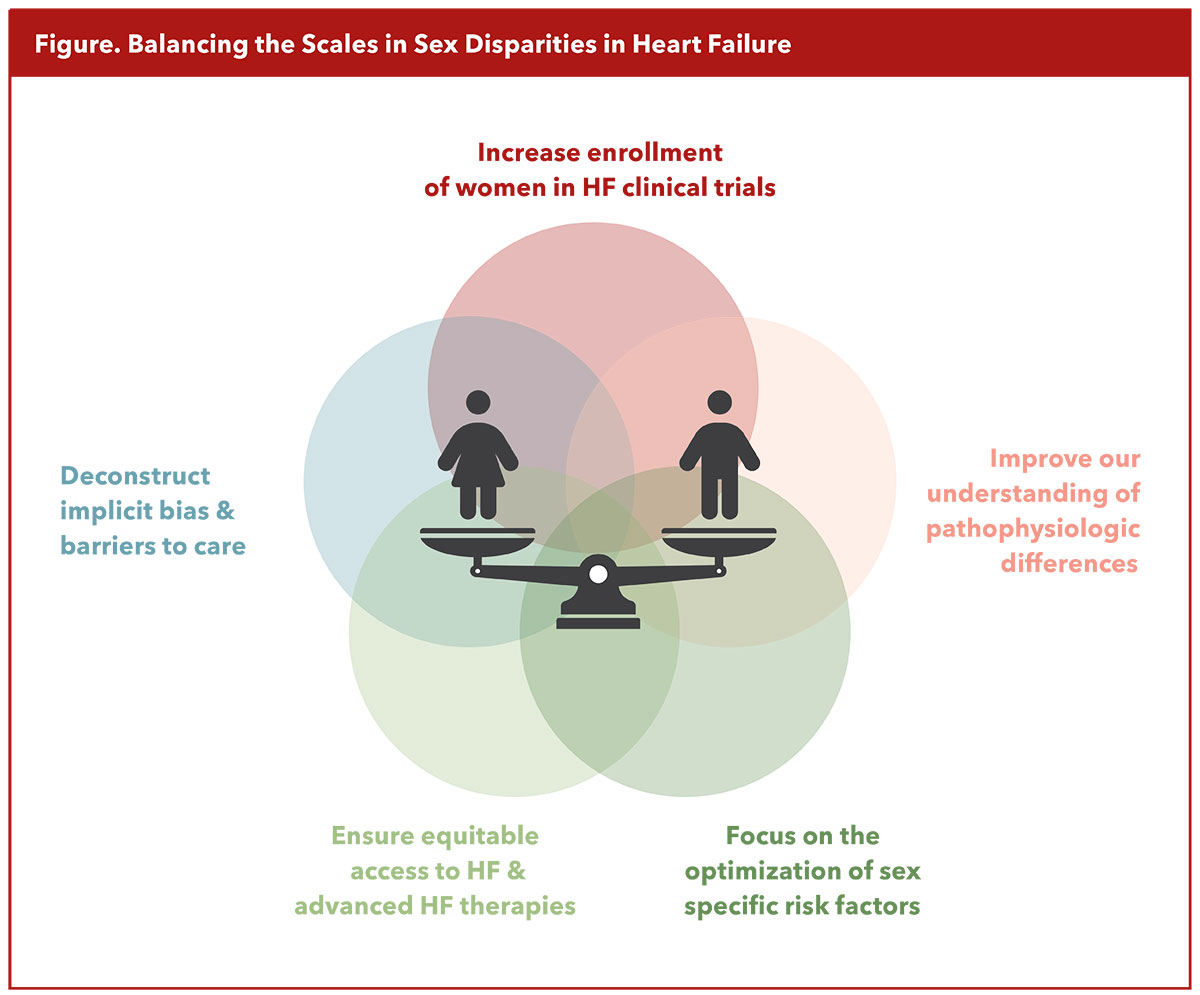

We have highlighted here recent advances in the understanding of sex-differences in HF. Despite significant progress, there remain more questions than answers. As eloquently stated by Mary Norine Walsh, MD, MACC; Mariell Jessup, MD, FACC; and JoAnn Lindenfeld, MD, FACC, in a JACC article title,29 "Women with Heart Failure: Unheard, Untreated, and Unstudied." Thus, an intentional multifaceted approach that includes a sex-specific focus on primary prevention, deconstructing implicit bias and other barriers to care, ensuring adequate access to and implementation of tailored risk stratification and management regimens, and finally, the enrollment of women in adequate numbers in HF clinical trials, is necessary to balance the scales in sex disparities in HF (Figure).

This article was authored by Jessica Schultz, MD, AACC, an advanced heart failure and transplant cardiologist and assistant professor of medicine, and Bhavadharini Ramu, MD, FACC, an advanced heart failure and transplant cardiologist and associate professor of medicine, both at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. Reach out to Ramu on @DhariniRamu.

References

- Cushman M, Shay CM, Howard VJ, et al. Ten-year difference in women's awareness related to coronary heart disease: Results of the 2019 American Heart Association national survey. Circulation 2021;143: e239–e248.

- Lala A, Tayal U, Hamo CE, et al. Sex differences in heart failure. J Card Fail 2022;28:477-98.

- Lam CSP, Arnott C, Beale AL, et al. Sex differences in heart failure. Eur Heart J 2019;40:3859-68.

- Ramu B, Cogswell R, Ravichandran AK, et al. Clinical outcomes with a fully magnetically levitated left ventricular assist device among women and men. JACC Heart Fail 2023;11:1692-1704.

- DeFilippis EM, Nikolova A, Holzhauser L, Khush KK. Understanding and investigating sex-based differences in heart transplantation. JACC Heart Fail 2023;11:1181-8.

- Shah SJ, Lam CSP, Svedlund S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of coronary microvascular dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: PROMIS-HFpEF. Eur Heart J 2018;39:3439-50.

- Schiattarella GG, Altamirano F, Tong D, et al. Nitrosative stress drives heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nature 2019:568:351-6.

- Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 2016;16:626-38.

- Beale AL, Nanayakkara S, Segan L, et al. Sex differences in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction pathophysiology: A detailed invasive hemodynamic and echocardiographic analysis. JACC Heart Fail 2019;7:239-49.

- Lundorff IJ, Sengelov M, Jorgensen PG, et al. Echocardiographic predictors of mortality in women with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Circ Cardiovasc Imag 2018; 11:e008031.

- Wolsk E, Kaye D, Komtebedde J, et al. Central and peripheral determinants of exercise capacity in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2019;7:321-32.

- Blenck CL, Harvey PA, Reckelhoff JF, Leinwand LA. The importance of biological sex and estrogen in rodent models of cardiovascular health and disease. Circ Res 2016;118:1294-312.

- Lam CSP, Cheng S, Choong K, et al. Influence of sex and hormone status on circulating natriuretic peptides. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:618-26.

- Savji N, Meijers WC, Bartz TM, et al. The association of obesity and cardiometabolic traits with incident HFpEF and HFrEF. JACC Heart Fail 2018;6:701-9.

- Galderisi M, Anderson KM, Wilson PWF, Levy D. Echocardiographic evidence for the existence of a distinct diabetic cardiomyopathy (The Framingham Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 1991;68:85-9.

- Levy D, Larson MG, Vasan R, et al. The progression from hypertension to congestive heart failure. JAMA 1996;275:1557-62.

- Higgins ST, Kurti AN, Redner R, et al. A literature review on prevalence of gender differences and intersections with other vulnerabilities to tobacco use in the United States, 2004–2014. Prev Med 2015;80:89-100.

- Dewan P, Rørth R, Jhund PS, et al. Income inequality and outcomes in heart failure: A global between-country analysis. JACC Heart Fail 2019;7:336-46.

- Carlson S, Schultz J, Ramu B, Davis MB. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: Risks diagnosis and management. J Multidiscip Healthc 2023;16:1249-58.

- Abdel-Qadir H, Austin PC, Lee DS, et al. A population-based study of cardiovascular mortality following early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2:88-93.

- Chen J, Long JB, Hurria A, et al. Incidence of heart failure or cardiomyopathy after adjuvant trastuzumab therapy for breast cancer. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:2504-12.

- Soldin O, Mattison D. Sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacokinet 2009;48:143-57.

- Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS, et al. Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1609-20.

- Merrill M, Sweitzer NK, Lindenfeld J, Kao DP. Sex differences in outcomes and responses to spironolactone in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A secondary analysis of TOPCAT trial. JACC Heart Fail 2019;7:228-38.

- Ghanbari H, Dalloul G, Hasan R, et al. Effectiveness of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for the primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in women with advanced heart failure: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1500-6.

- Arshad A, Moss AJ, Foster E, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy is more effective in women than in men: The MADIT-CRT (multicenter automatic defibrillator implantation trial with cardiac resynchronization therapy) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:813-20.

- Chan V, Chen L, Messika-Zeitoun D, et al. Is late left ventricle remodeling after repair of degenerative mitral regurgitation worse in women? Ann Thorac Surg 2019;108:1189-93.

- Herr JJ, Ravichandran A, Sheikh FH, et al. Practices of referring patients to advanced heart failure centers. J Card Fail 2021;27:1251-9.

- Walsh MN, Jessup M, Lindenfeld J. Women with heart failure: Unheard, untreated, and unstudied. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:41-3.

Clinical Topics: Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Acute Heart Failure

Keywords: Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications, Heart Failure, Sex Characteristics, Inflammation