For the FITs | Diversity in Clinical Trials: How FITs Can Help

I do not want to be a lab rat.

This is what a patient who self-identified as Black told me when I attempted to obtain his approval to discuss his case and allow a physical examination during our fellowship weekly bedside teaching rounds.

Yet, another patient who also self-identified as Black consented to noninvasive functional cardiac testing without any explanation from me about the test protocol and its risks and benefits, stating she trusted I will do the best for her because I look like her.

These two divergent responses can be expected when we discuss clinical trials with underrepresented patients. Fellows in Training (FITs) can play a vital role in helping to diversify the patient population of trials starting with understanding the current situation and taking some simple steps to be prepared to talk with our patients.

Scope of the Issue

The prevalence of cardiovascular disease is higher among Non-Hispanic Black women and men than in other race/ethnic groups,1 however, there is limited representation of minority patients in cardiovascular disease trials despite efforts by the U.S. government and regulatory bodies to address this.2,3

The disparities in reporting race/ethnicity information and enrollment of minority patients in randomized clinical trials of cardiovascular disease is highlighted by a systematic review that examined results from such trials published between 1997 and 2010 in three major journals (JAMA, New England Journal of Medicine, and The Lancet).4

Among 250 trials, 140 (56%) included race/ethnicity information and the median percentage of White, Black, Hispanic and Asian patients enrolled was 86%, 7%, 6% and 4%, respectively.

Tips For Getting Involved in Clinical Trial Diversity

- Make time to read the FDA guidance on diversity in clinical trials.

- Make a list of clinical trials enrolling at your institution and store it in your smartphone.

- Talk with your patients about the benefits of participation and take time to address their concerns.

Of note, the review found that the enrollment of White patients was significantly higher compared to their percentage of the U.S. population during that time period (86% vs. 74%; p<0.01), while there was no difference among other race/ethnic groups (Black patients 7% vs. 12%; Hispanic patients 6% vs. 10%; Asians 4% vs. 4%). However in coronary artery disease (CAD) trials, Black patients were underrepresented (3% vs. 13%; p<0.01).4

This underrepresentation of Black patients is also seen in clinical trials of peripheral artery disease (PAD), although Black women and men suffer a higher prevalence and mortality from PAD than Non-Hispanic White patients.

Only four of 14 clinical trials in PAD with results published between 2012 and 2022 reported information on race/ethnicity – revealing an enrollment rate of 4.3% Black, 3% Hispanic, 16% Asian and 75% White patients.1,6

Reassuringly in heart failure trials, there has been improvement in reporting of race/ethnicity information and enrollment of minority participants. In a review of 414 clinical trials there was nearly a doubling from 30% in 2000-2003 to 55% in 2016-2020. In addition, enrollment of minority patients increased during the same time interval from 14% to 22%.7

Remembering Our History

Why is there lack of diversity in clinical trials? First, looking back, mistrust among many minority patients in the process of scientific investigations stems from the unpleasant history of minority involvement in clinical research.

The Tuskegee syphilis experiment conducted among Black men in Macon County, AL, between 1932 and 1972 by the U.S. Public Health Services is one, among many, that is often brought up.8

Second, disparities in access to health care limit access for minority patients to receive care at or be referred to institutions more likely to be clinical trial enrollment sites.

A national inpatient sample from 2011 to 2016 showed that Black and Hispanic patients were less likely to undergo transcatheter aortic valve replacement, transcatheter mitral valve repair and left atrial appendage occlusion than White patients.9

Third, there is a lack of diversity, particularly minorities, among trialists and clinical trial teams. This becomes important to break language barriers, foster trust, and enable minorities to successfully navigate the complex processes of participating in clinical trials.

There is no doubt that participating in clinical trials is time and resource consuming, especially the close monitoring and follow-up required. The time commitment can be challenging to minorities who may have inflexible work schedules, caregiver responsibilities, and limited resources for transportation to clinical enrollment sites.

Lastly, many clinical trial sponsors have not made it a priority to ensure enrollment of minorities to improve representation in clinical trials.

Tackling the Issue

Resources

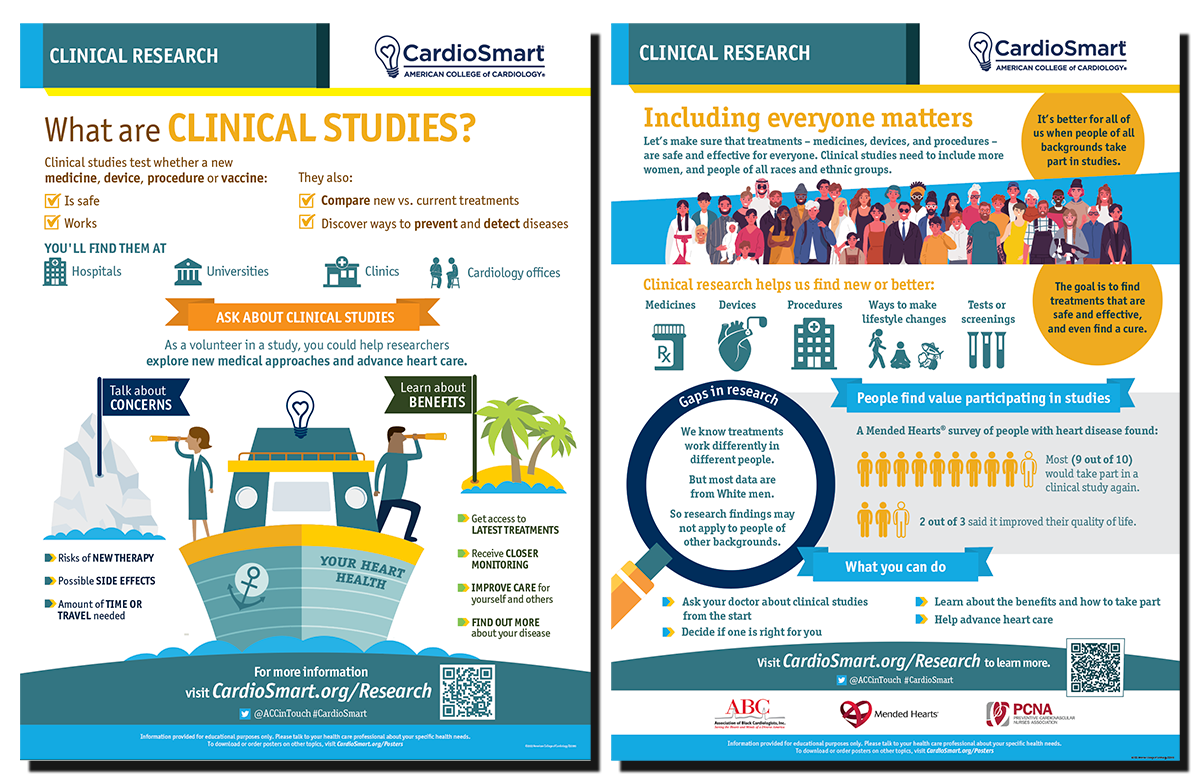

Click here to download CardioSmart infographics to help inform conversations with patients.

Click here and here to download FDA guidance documents on diversity in clinical trials.

Deliberate efforts are needed to improve diversity in clinical trials. Guidance for industry sponsors for improving the diversity in clinical trial populations from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is one such effort.

A diversity action plan for trials is recommended and must include goals of enrollment of participants by race, ethnicity, sex and age categories influenced by the incidence and prevalence of the disease in the intended use population; reason for the goals of enrollment; strategies for meeting these goals; and monitoring plan to ensure goals are met.10

The documents also discuss how to make trial participation less burdensome for participants and enrollment and retention practices.

Similarly, independent organizations are now sponsoring clinical trials to address interventions in underrepresented populations. The REvascularization CHoices Among under-Represented Groups Evaluation (RECHARGE) program sponsored by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) is addressing the lack of diversity of women and minorities in past studies assessing revascularization in obstructive CAD.

This program includes two multicenter, randomized, open-label superiority trials: RECHARGE: Women (NCT 06399692) will enroll 600 women and RECHARGE: Minorities (NCT 06399705) will enroll 600 Black or Hispanic patients.

All patients will have an indication for revascularization as assessed by the local Heart Team, with equipoise between PCI and CABG, and will be randomized to either strategy.11

The primary endpoint is a hierarchical composite of death and quality of life through five years.

From a broader perspective, interventions aimed at improving diversity in clinical trials can be implemented at three levels: trial design, trial conduction and trial results dissemination.

During trial design, efforts should be made to ensure diversity among trialists (principal investigators, co-principal investigators, site investigators) and the research team.

Community leaders and faith organization leaders should be engaged as resources for their unique perspective on community engagement and to serve as champions for building trust with the communities, which is essential in communities with predominantly minority patients.

To be more deliberate, enrollment quota for minority participants should be set to reflect the prevalence of the disease in that population.

In the trial conduction phase, recruitment sites should be expanded to include centers that serve diverse patient populations and supported with appropriate resources to successfully enroll patients. FITs are likely to take care of patients with lower socioeconomic status, including minority patients, in their clinics.

Therefore, it's crucial for FITs to be well informed about the ongoing clinical trials at their institutions. FITs can leverage their established therapeutic relationships with these patients to provide the appropriate information regarding relevant clinical trials and help navigate the patients through the complex process.

Reducing the burden of participation in clinical trials to a minimum is vital. This can be achieved by avoiding unnecessary testing/follow-up in addition to providing transportation, meal vouchers, flexible hours for follow-up visits, some compensation for income lost due to time off, and a dependent care program.

Lastly, harnessing the advantages of technology and its wide availability should be explored to find novel ways to conduct trials and capture a diverse patient population.

A key step that must not be overlooked is ensuring the final results from clinical trials are provided to the community, along with progress reports along the way. This solidifies trust with the community and this trust can extend to other communities, as well as from generation to generation.

Now is the Time

As a scientific community, it's time for us to collectively support conducting cardiovascular disease trials with participants who look like the ones we treat in our practice.

We must gain the evidence to know whether a given treatment will be effective for each patient we take care of every day. It's time to be deliberate in our actions to address the myriad of barriers that limit the diversity in clinical trials.

FITs must be active in this effort. We're on the frontline and we can help make a difference.

This article was authored by Oludamilola "Dami" Akinmolayemi, MD, MPH, a second-year cardiovascular disease fellow at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, NY. Reach out to him @DAkinmolayemi. Click here to join the FIT Member Section.

References

- Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. 2024 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024;149:e347-e913.

- National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993. Congress.gov. Accessed Oct. 27, 2024. Available here.

- Enhancing the Diversity of Clinical Trial Populations – Eligibility Criteria, Enrollment Practices, and Trial Designs Guidance for Industry. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Updated April 2024. Accessed Oct. 27, 2024. Available here.

- Zhang T, Tsang W, Wijeysundera HC, Ko DT. Reporting and representation of ethnic minorities in cardiovascular trials: a systematic review. Am Heart J 2013;166:52-7.

- Tahhan AS, Vaduganathan M, Greene SJ, et al. Enrollment of older patients, women, and racial/ethnic minority groups in contemporary acute coronary syndrome clinical trials: A systematic review. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5(714-22.

- Long C, Williams AO, McGovern AM, et al. Diversity in randomized clinical trials for peripheral artery disease: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health 2024;23:29.

- Wei S, Le N, Zhu JW, et al. Factors associated with racial and ethnic diversity among heart failure trial participants: A systematic bibliometric review. Circ Heart Fail 2022;15:e008685.

- Rusert B. "A study in nature": the Tuskegee experiments and the New South plantation. J Med Humanit 2009;30:155-71.

- Alkhouli M, Alqahtani F, Holmes DR, Berzingi C. Racial disparities in the utilization and outcomes of structural heart disease interventions in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e012125.

- Diversity Action Plans to Improve Enrollment of Participants from Underrepresented Populations in Clinical Studies. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed Oct. 29, 2024. Available here.

- The Recharge Trial. Recharge Trial. Accessed Oct. 29, 2024. Avialable here.

Keywords: Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications, Clinical Trial, Cultural Diversity, Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, Health Equity, Ethnic Groups