Anomalous Aortic Origin of the Coronary Artery

Quick Takes

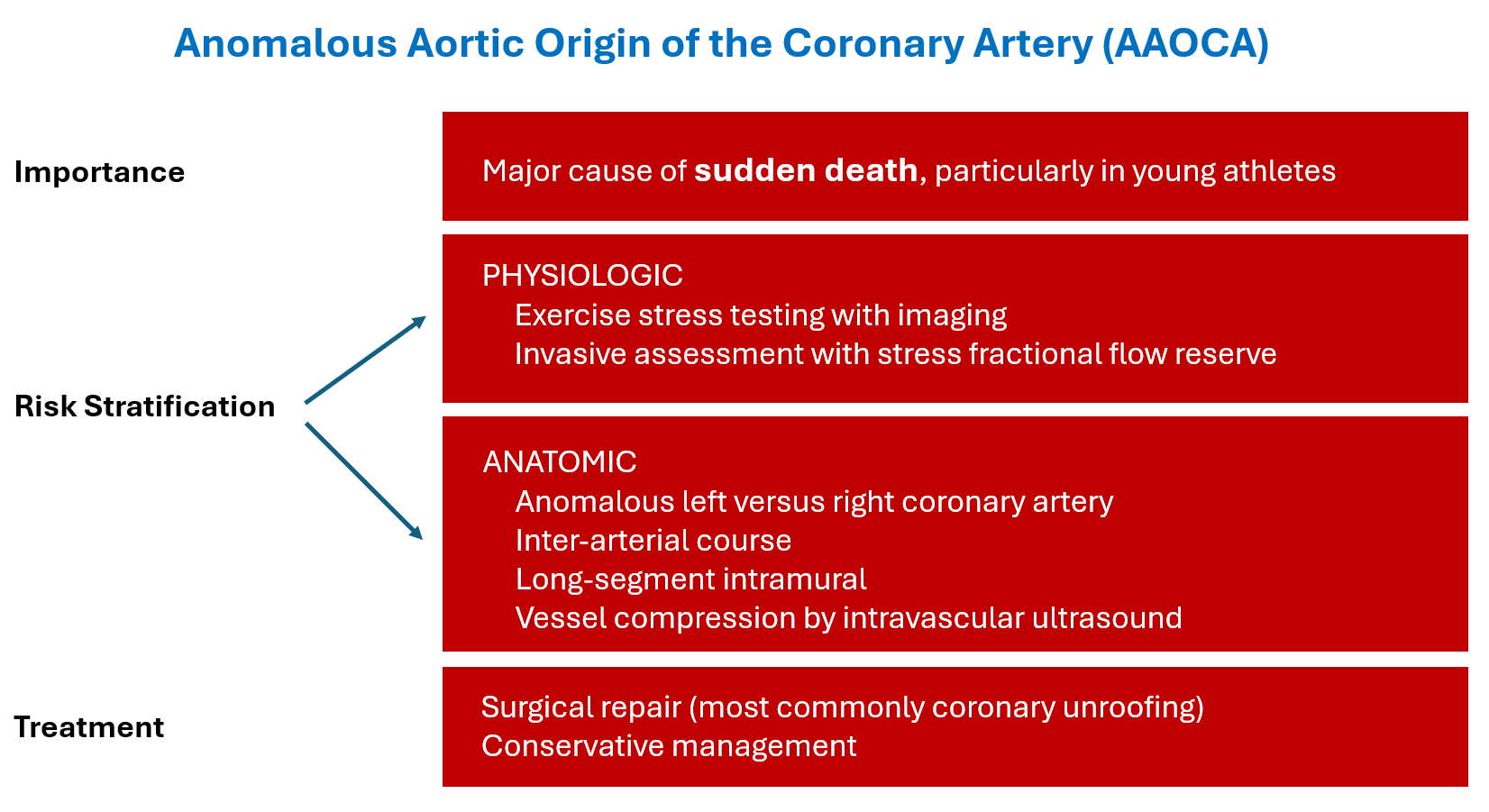

- Anomalous aortic origin of the coronary arteries (AAOCA) is a rare but important cause of sudden cardiac death, particularly in young athletes.

- Risk assessment of AAOCA includes anatomical and functional testing, but multimodality approaches including both noninvasive and invasive techniques are favored given the poor sensitivity of any test used in isolation.

- Surgery carries a low risk of death but a significant risk of new aortic regurgitation, unresolved ischemia, and reoperation.

Anomalous aortic origin of the coronary arteries (AAOCA) is a rare congenital heart condition that represents the second leading cause of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in young athletes.1 It is theorized that occlusion or compression of the coronary vessel during exertion leads to myocardial ischemia and ventricular arrhythmia, resulting in SCD.1 In a 20-year study of National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) athletes, 8.5% of SCD cases were due to AAOCA, all of which occurred in the context of exertion.2 Although such cases suggest a clear and grave danger, the same anatomy is often identified incidentally in individuals undergoing imaging for other indications.3 A risk-stratification strategy must therefore consider both the young competitive athlete and the older adult participating in light exercise for fitness.

Risk-stratification strategies for these patients includes both functional testing to assess for inducible ischemia and anatomical evaluation for identification of high-risk features, such as an interarterial course, long intramural course, slit-like ostium, or acute angle take-off.4-6 For identification of ischemia, stress testing with imaging (e.g., nuclear perfusion imaging or stress echocardiography) is recommended given the low sensitivity of exercise stress testing alone.7 However, different stress modalities may be discordant with one another and have been found to correlate poorly with exertional symptoms.7 As a result, other methods of assessing for ischemia noninvasively are currently being studied, although their clinical utility remains to be seen.

Coronary angiography remains the reference standard for assessing the lumen of the vessel and any intramural segment of an anomalous coronary. Intravascular ultrasonography can visualize compression during pharmacologic stress, and fractional flow reserve can quantify any pressure decrement across the vessel.8 The benefit of invasive evaluation for risk stratification is currently being investigated as part of the MuSCAT (Multicentre Study on Coronary Anomalies in the Netherlands), with interim analysis showing that 24% of patients had their treatment plan changed on the basis of invasive hemodynamic assessment findings.8 Given the rarity of SCD, a reliable risk-stratification scheme is difficult to establish; most studies use surrogate endpoints such as ischemia by stress testing or referral for surgery rather than ventricular arrhythmia or SCD itself.

Regarding noninvasive anatomical assessment, large-scale prospective data are lacking, but available studies suggest anomalous aortic origin of the left coronary artery (AAOLCA) poses higher risk than anomalous aortic origin of the right coronary artery (AAORCA). Two recent studies provide insight: one from Texas Children's Hospital reporting 4-year prospective follow-up on 220 young patients with both AAOLCA and AAORCA, and another multicenter study with an ambispective cohort from the Congenital Heart Surgeons' Society (CHSS).4-6 These studies found that AAOLCA is approximately four times less common than AAORCA but carries a significantly higher risk of ischemia—findings consistent with prior data.4,5 In the Texas cohort, 13% of those with AAOLCA had aborted SCD as part of their initial presentation, whereas none in the AAORCA cohort had any SCD.4,5 In the CHSS study, mortality rates were 5.5% for those with AAOLCA and 1.4% for those with AAORCA over up to 18 years of follow-up, which is in line with prior observational cohorts.6

The designation of high-risk anatomical features has the same pitfalls as other risk-stratification schemes. Interarterial course, particularly of AAOLCA, is the most well-established high-risk feature.4 Data supporting the high-risk nature of other anatomical characteristics are limited. Intraseptal course of AAOLCA had previously been considered a benign entity, for example, but as many as 35-50% of these patients have been found to have inducible ischemia and exertional symptoms in one study.4 In contrast, long intramural course, another high-risk characteristic, was not associated with ischemia in the AAORCA cohorts mentioned earlier. Even interarterial course of AAORCA, when discovered in middle age with at least one additional high-risk feature had favorable outcomes in up to 8 years of follow-up.5,9 High-risk anatomical features must be considered with great caution in the context of these data.

Ultimately, the risk of the lesion must be balanced against the potential risk and benefit of cardiac surgery. Coronary artery bypass surgery may result in limited graft patency due to competitive flow. According to the largest series on surgical repair of AAOCA, the risks of complications or ongoing ischemia after surgery are appreciable. A CHSS multicenter study of 395 patients (median age 12.9 years) reported that the most common operation for AAOCA was surgical unroofing, and acute surgical mortality was <1%.10 Adverse events were seen in 6-13% of patients, including new aortic regurgitation, newly reduced ejection fraction, coronary and noncoronary reoperations, and death.10 Risk was highest among those with preoperative ischemia (23%) and AAOLCA (15%), although resolution of preoperative ischemia was seen in approximately 80% of patients.10 Given these risks and the low incidence of SCD, conservative management may be appropriate for many patients, particularly those with AAORCA and no documented ischemia.

Despite a growing evidence base for patients with AAOCA, the true prevalence of the lesion and incidence of ischemia and SCD are unknown. Risk assessment remains challenging with current consensus statements favoring multimodality approaches. Surgery remains the treatment of choice for those with documented ischemia; although mortality rates are low, there remains a significant complication rate and it may not eliminate ischemia in all cases (Figure 1). Further research is required to understand the long-term outcomes of surgery and to refine risk, particularly in older adults with incidentally discovered lesions.

Figure 1: Anomalous Aortic Origin of the Coronary Arteries

References

- Molossi S, Doan T, Sachdeva S. Anomalous coronary arteries: a state-of-the-art approach. Cardiol Clin. 2023;41(1):51-69. doi:10.1016/j.ccl.2022.08.005

- Petek BJ, Churchill TW, Moulson N, et al. Sudden cardiac death in national collegiate athletic association athletes: a 20-year study. Circulation. 2024;149(2):80-90. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.065908

- Li K, Hu P, Luo X, et al. Anomalous origin of the coronary artery: prevalence and coronary artery disease in adults undergoing coronary tomographic angiography. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2024;24(1):271. Published 2024 May 23. doi:10.1186/s12872-024-03942-8

- Doan TT, Wilkes JK, Reaves O'Neal DL, et al. Clinical presentation and medium-term outcomes of children with anomalous aortic origin of the left coronary artery: high-risk features beyond interarterial course. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16(5):e012635. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.122.012635

- Doan TT, Sachdeva S, Bonilla-Ramirez C, et al. Ischemia in anomalous aortic origin of a right coronary artery: large pediatric cohort medium-term outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16(4):e012631. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.122.012631

- Jegatheeswaran A, Devlin PJ, McCrindle BW, et al. Features associated with myocardial ischemia in anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery: a Congenital Heart Surgeons' Society study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;158(3):822-834.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.02.122

- Qasim A, Doan TT, Dan Pham T, et al. Is exercise stress testing useful for risk stratification in anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery?. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023;35(4):759-768. doi:10.1053/j.semtcvs.2022.08.009

- Verheijen DBH, Van Der Kley F, Egorova AD, et al. Invasive testing leads to significantly altered (surgical) management strategy in coronary anomalies with interarterial course: 3 year interim analysis of MuSCAT. Eur Heart J. 2024:45(Supplement_1):ehae666.2123. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehae666.2123

- Albuquerque F, de Araújo Gonçalves P, Marques H, et al. Anomalous origin of the right coronary artery with interarterial course: a mid-term follow-up of 28 cases. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):18666. Published 2021 Sep 21. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-97917-w

- Jegatheeswaran A, Devlin PJ, Williams WG, et al. Outcomes after anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery repair: a Congenital Heart Surgeons' Society study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;160(3):757-771.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.01.114

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiac Surgery, Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Atherosclerotic Disease (CAD/PAD), SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and CHD and Pediatrics, Congenital Heart Disease, CHD and Pediatrics and Arrhythmias, CHD and Pediatrics and Interventions, Interventions and Coronary Artery Disease, Interventions and Structural Heart Disease, Sports and Exercise Cardiology, Stable Ischemic Heart Disease

Keywords: Anomalous Left Coronary Artery, Death, Sudden, Cardiac, Heart Defects, Congenital, Cardiac Surgical Procedures, Coronary Artery Disease