Clinical Practice Guidelines For Improving South Asian Cardiometabolic Health

Quick Takes

- The American Society for Preventive Cardiology (ASPC) clinical practice statement titled South Asians and Cardiometabolic Health: A Framework for Comprehensive Care for the Individual, Community, and Population provides a roadmap for clinicians, communities, and academia to address cardiometabolic disease in South Asian (SA) individuals residing in North America.

- Mental health, pregnancy outcomes, cardiac imaging, and SA cardiometabolic prevention clinics are emerging domains that need greater attention to adequately address disproportionate health outcomes between SA and other racial and ethnic groups.

- Developing effective community interventions and lifestyle modification programs is an important part of taking action on mitigating known risk factors.

Commentary is based on Rohatgi A, Anand SS, Gadgil M, et al. South Asians and cardiometabolic health: a framework for comprehensive care for the individual, community, and population - an American Society for Preventive Cardiology clinical practice statement. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2025;22:101000. Published 2025 Apr 22. doi:10.1016/j.ajpc.2025.101000

South Asian (SA) adults residing in North America face a high burden of cardiometabolic risk due to a combination of genetics, lifestyle, mental and reproductive health factors, and chronic conditions including diabetes mellitus (DM) and hypertension (HTN).1 Ongoing research has revealed disparities faced by SAs compared with other racial and ethnic groups. As a result of these disparities, unique cultural considerations are necessary to provide appropriate risk factor reduction.2 Clinical practice guidelines and statements with ethnic-specific recommendations for optimizing the cardiovascular (CV) care of SAs have not been well synthesized.

This unmet need led the American Society for Preventive Cardiology(ASPC) to construct guidance for a broad spectrum of diseases and risk factors related to cardiometabolic disease focused on the care of SAs.1 These comprehensive recommendations cover optimal nutrition, physical activity, and management of common conditions including DM, HTN, and dyslipidemia. Beyond these, the statement discusses evolving areas including adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs), mental health considerations, coronary atherosclerosis and cardiac imaging, genetic testing, social drivers of health, and SA cardiometabolic prevention clinics. The statement underscores that greater awareness and education are needed in the prevention and management of these risk factors for heart disease in this particularly vulnerable population. Community and religious leaders, clinicians, and other health care providers have been identified as important agents through which risk can be mitigated by promoting research enrollment, initiating early treatment and prevention, and advocating for best health practices among SA populations. An overview of the guidelines translated into a patient perspective is included as Table 1.

Table 1: Patient Guidance for Managing Cardiometabolic Risk

|

Category

|

Guidance for Patients

|

| Nutrition and physical activity |

|

| DM |

|

| HTN |

|

| Dyslipidemia |

|

| Adiposity |

|

| APOs |

|

| Mental health |

|

| Coronary atherosclerosis and cardiac imaging |

|

| Genetic testing |

|

| SA cardiometabolic prevention clinics |

|

APO = adverse pregnancy outcome; apo B = apolipoprotein B; BMI = body mass index; BP = blood pressure; CAC = coronary artery calcium; CVD = cardiovascular disease; DM = diabetes mellitus; HTN = hypertension; Lp(a) = lipoprotein(a); SA = South Asian; T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Commentary

To mitigate cardiometabolic risk among SA populations, interventions at the community, clinical, and research levels should be pursued. In the community domain, interventions focusing on broader programmatic and systemic changes, such as the development of dietician training programs specifically focused on SA populations, should be implemented. These types of interventions seek to build prevention capacity and raise awareness within the community.

In the clinical setting, health care workers have opportunities to mitigate risk through education and screening. For example, screening for and treating depression through the VitalSign6 model (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center) offers a comprehensive approach to addressing mental health through primary care provider–driven care.3 Regarding APOs, employing birthing and postpartum staff from concordant cultural backgrounds and addressing CV health in the third trimester and postpartum can help improve cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes.

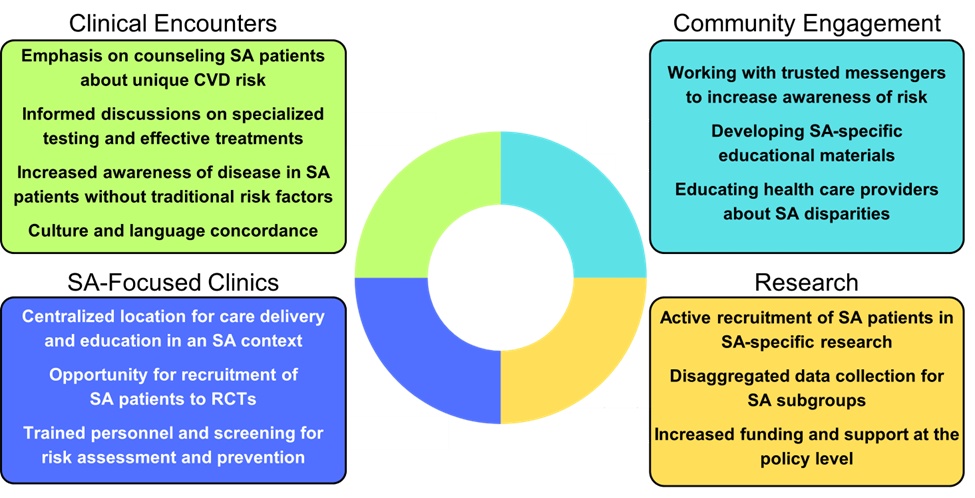

SA are wholly underrepresented in clinical trials and registries worldwide.4 Specifically, gaps exist in the development of SA-validated CVD risk prediction scores to optimize treatment of DM, obesity, and dyslipidemia. Genome-wide association studies do not adequately represent SAs and would benefit from additional cohort diversification.5 These research gaps should be ideally addressed through targeted recruitment efforts that use appropriate messengers and conduct proactive outreach in the SA community. Structural change at a policy level such as through the national South Asian Heart Health Awareness and Research Act of 2022 or state-level ISMA Resolution 24-006 (approved to increase awareness of SA heart health in Indiana) are needed to direct research dollars and appropriately resource studies.6 Figure 1 provides a framework highlighting important clinical, community, and research considerations.

Figure 1: Addressing South Asian Health Disparities in Four Domains

CVD = cardiovascular disease; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SA = South Asian.

The guidelines also highlight mental health, pregnancy outcomes, cardiac imaging, and SA cardiometabolic prevention clinics as important topics that have historically received less attention in the SA health disparities literature. Lack of attention to these areas signals an opportunity for intervention at all levels of care. APOs, such as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), occur in 18-20% of pregnancies. SA have elevated rates of GDM, and there is limited evidence for the absolute magnitude and relative importance of the relationships between specific APOs and CV outcomes among SA females.7 Similarly, mental health in the SA population and its link to cardiometabolic disease has not been well studied. Prevalence estimates and pathophysiological mechanisms of major mood and anxiety disorders are unknown, providing significant barriers to allocation of appropriate resources for diagnosis and treatment.8

Perhaps one of the greatest opportunities to address disparities is the establishment of SA cardiometabolic prevention clinics.9 These sites can integrate risk factor screening and comprehensive risk factor reduction within a collaborative environment. They are well situated to provide multidisciplinary treatment and education regarding nutrition, exercise, mental health, and primary care in a culturally tailored context with providers trained in working with SA populations. They also serve as a central location for community outreach to religious centers and SA community hubs alongside being able to initiate and run research efforts for understudied topics within SA health.10

Indeed, the SAHELI (South Asian Healthy Lifestyle Intervention) and SAHARA (South Asian Heart Risk Assessment) trials provide an important starting point by demonstrating that culturally tailored interventions are feasible and can engage SA communities. However, expanded research on methodologies is necessary to find evidence-based strategies that are effective in mitigating cardiometabolic risk.11 At Johns Hopkins, the South Asian Medical Student Association in collaboration with the South Asian Cardiometabolic Clinic through the Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease created a community health fair intervention at local mandirs (temples) that incorporates SA-specific health risk education and screenings for DM and HTN, which is hoped to be validated as a model and expanded. Similar community-level interventions, such as the Utah South Asian Cardiovascular Health Initiative (U-SACHI), have been used to screen for and mitigate cardiometabolic disease.12

In summary, a comprehensive, multipronged approach that involves all stakeholders—from community members to research teams to health care workers—will be the most impactful way to optimize the identification, prevention, and treatment of CVD among SA in the United States.

References

- Rohatgi A, Anand SS, Gadgil M, et al. South Asians and cardiometabolic health: a framework for comprehensive care for the individual, community, and population - an American Society for Preventive Cardiology clinical practice statement. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2025;22:101000. Published 2025 Apr 22. doi:10.1016/j.ajpc.2025.101000

- Agarwala A, Satish P, Rifai MA, et al. Identification and management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in South Asian populations in the U.S. JACC Adv. 2023;2(2):100258. doi:10.1016/j.jacadv.2023.100258

- Trivedi MH, Jha MK, Kahalnik F, et al. VitalSign6: a Primary Care First (PCP-First) model for universal screening and measurement-based care for depression. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2019;12(2):71. Published 2019 May 14. doi:10.3390/ph12020071

- Uppal N, Patel AP, Bhatt DL, Natarajan P. South Asian representation in cardiovascular disease randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. JACC Asia. Published online August 8, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jacasi.2025.06.017

- Martin AR, Kanai M, Kamatani Y, Okada Y, Neale BM, Daly MJ. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nat Genet. 2019;51(4):584-591. doi:10.1038/s41588-019-0379-x

- Jayapal P. H.R.4914 - South Asian Heart Health Awareness and Research Act of 2023: 118th Congress (2023-2024) (Congress.gov website). 2023. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/4914?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%22H.R.4914%22%7D&s=1&r=17. Accessed 10/06/2025.

- Shah NS, Wang MC, Freaney PM, et al. Trends in gestational diabetes at first live birth by race and ethnicity in the US, 2011-2019. JAMA. 2021;326(7):660-669. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.7217

- Karasz A, Gany F, Escobar J, et al. Mental health and stress among South Asians. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21(Suppl 1):7-14. doi:10.1007/s10903-016-0501-4

- Kulkarni A, Mancini GBJ, Deedwania PC, Patel J. South Asian Cardiovascular Health: Lessons Learned from the National Lipid Association Scientific Statement (ACC website).2021. Available at: https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2021/08/02/14/16/South-Asian-Cardiovascular-Health. Accessed 10/06/2025.

- Gulati RK, Husaini M, Dash R, Patel J, Shah NS. Clinical programs for cardiometabolic health for South Asian patients in the United States: a review of key program components. Health Sci Rev (Oxf). 2023;7:100093. doi:10.1016/j.hsr.2023.100093

- Vu M, Nedunchezhian S, Lancki N, Spring B, Brown CH, Kandula NR. A mixed-methods, theory-driven assessment of the sustainability of a multi-sectoral preventive intervention for South Asian Americans at risk for cardiovascular disease. Implement Sci Commun. 2024;5(1):89. Published 2024 Sep 13. doi:10.1186/s43058-024-00626-4

- Gullapalli N, Zahid H, Krishnan H, et al. UTAH SOUTH ASIAN CARDIOVASCULAR HEALTH INITIATIVE (U-SACHI)- RESULTS FROM THE INTERVENTION COHORT (JACC website). 2025. Available at: https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/S0735-1097(25)00835-6. Accessed 10/06/2025.

Clinical Topics: Prevention, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention

Keywords: Plaque, Atherosclerotic, Primary Prevention, Practice Guideline, Community Health Services, Ethnic Groups, Asia, Asian Americans