Searching the Patent Literature – A Valuable Skill For Cardiology Fellows, Even if You Never File One!

April 27, 2017 | Junaid Zaman, MD

Education

As a FIT, we have to search the medical literature and keep abreast of the latest clinical practice guidelines. However, filing a provisional patent after the Stanford Biodesign Innovation Course provided first-hand experience in an equally fascinating source of knowledge and ideas: the patent literature. Whether you're filing a patent or just browsing technologies that may shape the future, knowing how to rapidly screen large volumes of intellectual property filings is a skill that can yield insight into technology transfers and afford opportunities in medtech. The growing number of institutions offering a ‘Biodesign' fellowship program (1) also reflects a growing interest in medical technology and entrepreneurship among FITs. Furthermore, it is increasingly common for editors/reviewers to cite patents when reviewing your manuscript, so you should know the steps involved to help prepare your rebuttal letter!

Is an Invention Really New?

Under U.S. law, a patent is a right-granted to the inventor of a i) process, machine, article of manufacture, or composition of matter, ii) that is new, useful, and non-obvious. Many inventors focus on the utility or application of their invention, but arguably the most difficult standard to prove is that the invention is new, without prior public disclosures of any ‘prior art'. ‘Prior art' covers all information disclosed to the public including U.S. patents, foreign patents, journal and magazine articles, books and catalogues, websites and conference proceedings, to name but a few. Accordingly, the first job of any hopeful inventor before filing a patent, is to make sure the invention or idea has not been disclosed already.

The broad scope of ‘prior art' requires a thorough and comprehensive evaluation to ensure novelty. This process used to require visits to libraries or Patent and Trademark Resource Centers, but similar to the medical literature, this can now almost entirely be done online.

The Steps to a Patent Search

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has an excellent guide on its website on how to run a patent search. The guide runs through a classification-based system of searches. The full details are available as a handout or a video tutorial, but the brief outline can be summarised as follows:

- Brainstorm terms describing the invention. Specifically:

- What problem does the invention solve?

- What is the structure of the invention?

- What does it do? An example for a new atrial fibrillation (AFib) ablation catheter is shown in the table below.

- Use these terms to find initial relevant Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) to get a broad overview of the relevant categories.

- For our AFib example: CPC Scheme Cardiac Ablation – A61N Electrotherapy.

- Check CPC Classifications definition if available.

- For our new ablation catheter: A61N -Specially adapted apparatus, instruments, devices, or processes for the following types of therapy: electrotherapy, e.g. iontophoresis; magnetotherapy; radiation therapy; ultrasound therapy.

- Retrieve and review issued patents using CPC classifications identified. Use front page information (abstract and representative drawings) to screen.

- In-depth review of retrieved patents focusing on additional drawings, specifications and claims. Note frequently cited patents for further review.

- Review published patent applications using 2. Search abandoned and expired patents – which also count as prior art. Screen and examine as in steps 4 and 5.

- Broaden search using foreign patents, USPC, non-patent literature, older (pre-1970s) material. Professional help from a patent specialist attorney will usually uncover more, and is most beneficial once you have completed your own search. Don't forget to ask industry contacts and visit booths at meetings where latest technology may be on show.

| Area | Search terms |

|

Need addressed/problem solved? |

Heart rhythm disorder, cardiac fibrillation, biological rhythm disorder, AFib, palpitations, irregular heartbeats, tachyarrhythmias, spiral waves, re-entrant arrhythmia, multiple wavelets, pulmonary vein firing. |

|

Structure of the invention/how is it made? |

Catheter, wire, ablation, radiofrequency, cryoenergy, tube, deflectable, expandable, balloon, mesh, contact, non-contact, ultrasonic, electrical, basket, array. |

|

Function of the invention/what does it do? |

Ablate, cauterise, isolate, freeze, defragment, segment, heat, irrigation, burn, cool, block, terminate, restore, modulate. |

Other Search Strategies include:

- Keyword searching either on USPTO or Google Patents page. Use custom Boolean AND/OR or wildcard search features to keep breadth – ask librarian or check the USPTO website for help.

- Freedom to Operate (FTO) searches which look for claims within existing licensed patents that would impact some feature of the new concept so it is not possible to commercialize without licensing.

Briefly, FTO is the freedom to practice your invention without infringing upon the patent rights of others. For your new ablation catheter, if it required delivery via a sheath technology or energy system that was previously patented, the inventors of that could block you from doing so. This is best done with a patent specialist, as independent claims (which you have already screened in step 5 of your search) can be very complex, vague and long-winded to intentionally impact a wide range of future inventions.

Index, Iterate and Implement

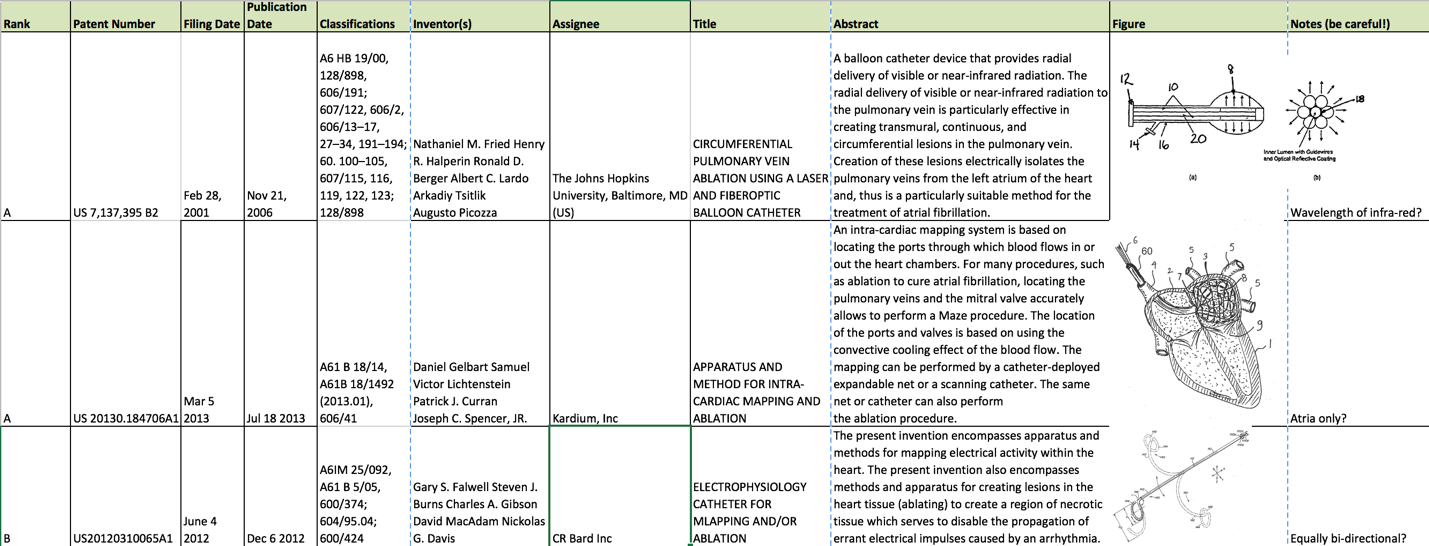

More so than with medical literature searches, you must make a note of the date, time and databases used as repeat searches can be much more efficient with even basic indexing. Diagrammatic indexing offers a rapid visual signature of patents. You should also keep the list of patents and download the full text of the most relevant ones so you can refer to them offline and annotate them. A great suggestion, which may benefit how you archive medical literature searches as well, was to keep a patent search table which provides easy and rapid access to key data.

Figure 1 - Click to Enlarge: Example of a patent search table for atrial fibrillation ablation catheters.

Can Searching Help You Develop Your Own Ideas?

Yes. As you browse the literature, keeping focussed on an area of interest (atrial fibrillation in our example) will help show what potential technologies are being developed, and the intellectual property (IP) landscape. If you plan to file a patent, you may need to search the patent and FTO literature at regular intervals. This means looking forward and backward using key citations, figures and classifications as search develops. Implementing this information from iterative searching may help you develop a better solution to any identified ‘need'.

Relevance to FITs

Most patents involve a team effort. Like any published manuscript, this means everyone contributes in some capacity. As a FIT, it is rare that you will develop an invention solo. Most likely, this may arise in a formal Biodesign program, which tend to gravitate to centres that will already have infrastructure to support you through the process. However, if the world of medical technology is one you find fascinating, alluring or inspiring, then knowing the basic language of patents and how to find one can be highly rewarding and enjoyable. The screening of patents in your field, or perhaps those written by mentors, is an exciting way to see what the future may look like from the eyes of an inventor. In a field as dynamic and innovative as cardiology, exemplified by the ACC focus on innovation, knowing the basics of a patent search can really help a FIT become a future leader of their field.

This article was authored by Junaid Zaman, MD, a Fellow in Training (FIT) at Stanford University.