Peripheral Matters | Peripheral Artery Disease: Moving From Awareness to Action

It has been a decade since the late cardiologist Alan Hirsch, MD, declared peripheral artery disease (PAD) the "last major pandemic of cardiovascular disease." In the years since this declaration, PAD has affected approximately 230 million people worldwide and approximately 8.5 million people in the U.S.1,2 Even more, in the U.S., PAD disparities based on race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education level, sexual orientation, gender identity, and geographic location have been well documented and contribute to suboptimal treatment and adverse outcomes.3-6

Hirsch also stated that "achieving health is not a personal burden. It's a family and community obligation that is easily achieved when we work together." With respect to PAD, the health care community has an obligation to not just be aware of PAD, but to intentionally act to diagnose, treat and manage the disease, particularly for the most at-risk and often overlooked populations. September is PAD Awareness Month, but we'd like to suggest that it be PAD "Action" Month. Here we provide key information to help clinicians take action for all their patients suffering with PAD.

Overview of PAD

PAD is an atherosclerotic disease characterized by the formation of atherosclerotic plaque that causes narrowing of the arteries and poor perfusion to the limbs which can progress to arterial occlusion and chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI).7,8 PAD is associated with impaired functional status, poor quality of life (QOL), and an increased rate of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.9-11

Only 10-30% of patients with PAD have claudication with exertional calf pain. The rest either are asymptomatic or have atypical leg symptoms. Risk factors include smoking, diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia. Smoking has more than double the association with PAD as well as worse clinical outcomes.9,12,13

CLTI is the most severe form of PAD leading to ulceration and foot gangrene and ultimately amputation.14 The one-year rate of major amputation is 22%, significantly deteriorating QOL and increasing mortality rates to about 35-48% within one year.13,15,16

Patients with PAD frequently visit their physicians and the emergency department and many require vascular procedures and hospitalizations that lead to significantly higher health care-related costs, with an average annual expenditure of $11,553 per patient.17 The cost of vascular-related hospitalizations has been estimated to be $21 billion in the U.S.18 The estimated treatment cost for vascular procedures is estimated to be $4.2 billion.19

PAD is associated with the poorest QOL and highest health care-related costs among all cardiovascular diseases.10 However, PAD continues to be underdiagnosed and undertreated.7,20 It is critical to enact change across the health care system to improve the quality of care and clinical outcomes for patients with PAD.

Special Populations Living With PAD

People of color – including Black Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, Asians and others – experience varying degrees of social disadvantage that increases their risk of poor PAD outcomes including mortality.6,21-27

A decade after a "call to action" in 2012 to prioritize vascular research and care for women,28 it is still not widely recognized that the prevalence and burden of PAD is equal, if not higher, in women compared with men.29 Women with symptomatic PAD tend to report more significant disability than men. Specifically, greater functional impairment, poorer outcomes after revascularization, worse health-related QOL and mental health concerns are cited as contributing factors.30-35

PAD disproportionately burdens Black Americans.36,37 Yet, Black Americans have the lowest reported awareness of PAD compared with other racial or ethnic groups with only 6% being aware of the morbid consequences of PAD.2 Moreover, Black Americans are less likely to receive intervention, experience greater comorbidity burden, and have higher rates of novel risk factors.38-41

Data are limited on the burden of PAD among Hispanic/Latino groups. And evidence shows rates of PAD are not homogenous. Compared with Mexican Americans, all other Hispanic/Latino background groups have a significantly higher odds of having PAD, with the odds nearly threefold higher among Cubans.42 More recent data reveal elevated odds of amputation among Hispanic patients hospitalized with PAD, as well as higher hospital mortality and medical expenses among Asian or Pacific Islander inpatients with PAD compared with non-Hispanic Whites.43 While evidence is growing, more is needed to investigate factors that influence PAD outcomes among respective Hispanic/Latino groups and Asian or Pacific Islander communities.

Data are lacking on the impact of PAD in American Indians/Native Americans, however, they have the highest odds of CLTI compared with non-Hispanic Whites.43 Similarly, Native Americans have >1.3-times the odds of a major amputation compared with Caucasians.44 More research is needed to elucidate factors influencing disease onset and outcomes in this group.

Assessing Suspected Lower Extremity PAD

Patients with suspected lower extremity PAD should be evaluated with a comprehensive medical history and symptom review along with a tailored physical examination.15,45 History taking focuses on lifestyle behaviors, dietary patterns, physical activity and functional status, as well as symptoms including claudication and other exertional nonjoint-related lower extremity symptoms, ischemic resting pain and walking impairment perception.

Physical examination includes checking lower extremity pulses, listening for vascular bruits, and inspecting the legs and feet for gangrene or nonhealing wounds. Importantly, the history and physical examination helps differentiate PAD from alternative diagnoses, including but not limited to Baker's cyst, spinal stenosis, venous claudication, joint arthritis, nerve root compression and chronic compartment syndrome.

Special attention should be placed on differences related to gender and race/ethnicity in the presentation of PAD. For example, women are more likely to present with asymptomatic PAD, and if symptomatic, they tend to present at an older age, have symptom onset at shorter walking distances and proportionately have more CLTI than men.46 Black Americans present at a younger age and suffer significant mobility loss.38,41

Screening for PAD starts with identifying those at increased risk for the disease:15,45

- Patients >65 years old

- Patients 50-64 years old plus atherosclerotic risk factors or family history of PAD

- Patients <50 years with diabetes plus one additional atherosclerotic risk factor

- Patients with known atherosclerotic disease in other vascular beds.

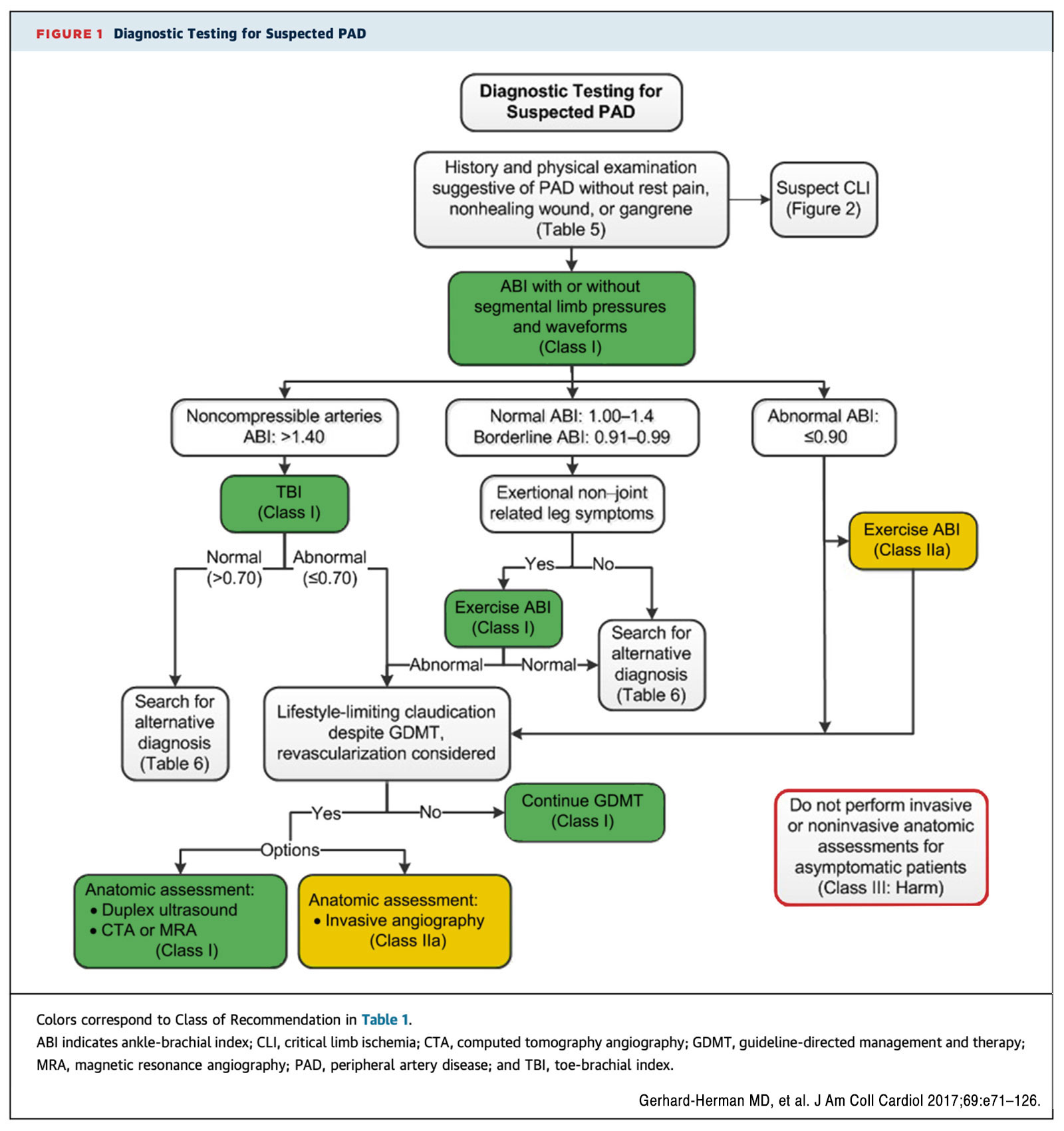

Diagnostic testing for suspected PAD starts with obtaining a resting ankle-brachial index (ABI), which is essential for the diagnosis and surveillance of PAD (Figure).45 It is an inexpensive tool for cardiovascular risk assessment independent of risk factors in different ethnic groups.45 Further physiologic testing with toe-brachial index (TBI) or exercise ABI and anatomic assessment with duplex US, computed tomography angiography, MR angiography or invasive angiography can be indicated based on the individual case.

Management of PAD

Medical treatment is the cornerstone of PAD management and includes lifestyle changes and risk factor modification to reduce the associated cardiovascular morbidity and should include a multifold approach. Management of comorbid conditions such as smoking cessation, cholesterol optimization, diabetes control, antihypertensive therapy and antiplatelet therapy are the focus of treatment.47 Conservative management includes hygienic and supportive measures to prevent skin breakdown and infection, proper self-foot exam techniques, biannual foot exam, and prompt treatment for wounds or skin infection.

First-line therapy for PAD includes a supervised exercise program and is shown to meaningfully improve pain-free walking distance and health-related QOL (including for those with aorto-iliac and femoro-popliteal disease) and is covered by insurance for symptomatic patients with PAD.15,48 In patients with ongoing symptoms despite exercise therapy, cilostazol is an effective medical therapy for alleviating leg symptoms.47

For patients with stable PAD, single antiplatelet therapy (SAPT) with aspirin or clopidogrel is recommended with clopidogrel the preferred SAPT.49 Rivaroxaban at a dose of 2.5 mg twice daily plus aspirin has been associated with a statistically significant lower incidence of the composite outcome of acute limb ischemia, major amputation for vascular causes, myocardial infarction, and ischemic stroke or death from cardiovascular causes without a difference in major TIMI (thrombolysis in myocardial infarction) bleeding.50,51 Further antiplatelet and antithrombotic therapy is summarized in Table 1.

Table 2 summarizes the management of comorbid conditions. The ACC/American Heart Association hypertension guideline recommends lower blood pressure treatment targets for patients at high cardiovascular risk (goal <130/80 mm Hg). These goals need to be carefully considered given that significantly low blood pressures may impair oxygen delivery to limbs and exacerbate symptoms of PAD.52

For patients with diabetes, even though no specific hemoglobin A1c cut-off has been defined, an increase in hemoglobin A1c levels by 1% has been shown to increase major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) by 14.2% – however, it is not yet proven if lowering hemoglobin A1c reduces MACE.53 Diabetes should be managed per diabetes guidelines and metformin, SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP1 agonists are therapeutic options.

Even though lipid management remains a moving target in this patient population, the 2022 European Atherosclerosis Society/European Society of Vascular Medicine guideline recommends a target LDL-C reduction >50% from baseline and <55 mg/dL.54

Revascularization is not indicated in patients with asymptomatic PAD and is commonly reserved for treatment of lifestyle-limiting symptoms that have persisted despite conservative measures or for CLTI.47 There is no evidence that symptomatic clinical outcomes can be improved or averted by prophylactic revascularization (endovascular or surgical).47 Occasionally iliac revascularization is indicated to facilitate passage/placement of large bore devices (percutaneous left ventricular assist device, TAVR, endovascular aortic repair).

It is prudent to treat inflow disease first (i.e., iliac and femoral arteries) for patients with claudication. In cases of CLTI, multilevel intervention is often necessary to establish straight-line flow to the affected limb and preferably towards affected tissue directly fed by the source artery (angiosome) For a patient presenting with CLTI, it is imperative to consider a consultation with the multidisciplinary care team and undertake comprehensive imaging before amputation to increase limb salvage.55

This article was authored by Demetria M. McNeal, PhD, MBA, Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO; Hussein Abu Daya, MD, MHA, FACC, Division of Cardiovascular Disease, Department of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine, Birmingham, AL; Leili Behrooz, MD, MPH, Whitaker Cardiovascular Institute, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA; and Sonal Pruthi, MD, Vascular Medicine and Intervention Fellow, Department of Cardiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Centre, New York, NY, All are members of ACC's Vascular Disease Section. Click here to join the Section today.

References

- Song P, Rudan D, Zhu Y, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2015: an updated systematic review and analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(8):e1020-e1030.

- Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9901):1329-1340.

- Jacob-Brassard J, Al-Omran M, Stukel TA, Mamdani M, Lee DS, de Mestral C. Regional variation in lower extremity revascularization and amputation for peripheral artery disease. Journal of vascular surgery. 2023.

- Jaiswal V, Hanif M, Ang SP, et al. Racial Disparity between the post-procedural outcomes among patients with Peripheral Artery Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Current problems in cardiology. 2023:101595.

- Luna P, Harris K, Castro-Dominguez Y, et al. Risk profiles, access to care, and outcomes in Hispanics hospitalized for lower extremity peripheral artery disease. Journal of vascular surgery. 2023;77(1):216-224.e215.

- Mota L, Marcaccio CL, Zhu M, et al. Impact of Neighborhood Social Disadvantage on the Presentation and Management of Peripheral Artery Disease. Journal of vascular surgery. 2023.

- Criqui MH, Matsushita K, Aboyans V, et al. Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: Contemporary Epidemiology, Management Gaps, and Future Directions: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;144(9):e171-e191.

- Lin J, Chen Y, Jiang N, Li Z, Xu S. Burden of Peripheral Artery Disease and Its Attributable Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories From 1990 to 2019. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:868370.

- Behrooz L, Abumoawad A, Rizvi SHM, Hamburg NM. A modern day perspective on smoking in peripheral artery disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1154708.

- Sigvant B, Lundin F, Wahlberg E. The Risk of Disease Progression in Peripheral Arterial Disease is Higher than Expected: A Meta-Analysis of Mortality and Disease Progression in Peripheral Arterial Disease. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery : The Official Journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2016;51(3):395-403.

- Patel KK, Jones PG, Ellerbeck EF, et al. Underutilization of Evidence-Based Smoking Cessation Support Strategies Despite High Smoking Addiction Burden in Peripheral Artery Disease Specialty Care: Insights from the International PORTRAIT Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(20):e010076.

- Peripheral arterial disease in people with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(12):3333-3341.

- Barnes JA, Eid MA, Creager MA, Goodney PP. Epidemiology and risk of amputation in patients with diabetes mellitus and peripheral artery disease. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2020;40(8):1808-1817.

- Abu Dabrh AM, Steffen MW, Undavalli C, et al. The natural history of untreated severe or critical limb ischemia. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2015;62(6):1642-1651.e1643.

- Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Patients With Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135(12):e726-e779.

- Abry L, Weiss S, Makaloski V, Haynes AG, Schmidli J, Wyss TR. Peripheral Artery Disease Leading to Major Amputation: Trends in Revascularization and Mortality Over 18 Years. Annals of Vascular Surgery. 2022;78:295-301.

- Scully RE, Arnaoutakis DJ, Smith AD, Semel M, Nguyen LL. Estimated annual health care expenditures in individuals with peripheral arterial disease. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2018;67(2):558-567.

- Mahoney EM, Wang K, Keo HH, et al. Vascular hospitalization rates and costs in patients with peripheral artery disease in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(6):642-651.

- Kolte D, Kennedy KF, Shishehbor MH, et al. Thirty-Day Readmissions After Endovascular or Surgical Therapy for Critical Limb Ischemia: Analysis of the 2013 to 2014 Nationwide Readmissions Databases. Circulation. 2017;136(2):167-176.

- Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286(11):1317-1324.

- Jaramillo EA, Smith EJT, Matthay ZA, et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Major Adverse Limb Events Persist for Chronic Limb Threatening Ischemia Despite Presenting Limb Threat Severity After Peripheral Vascular Intervention. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2022.

- Ries HC, Debus ES, Heidemann F, Stoberock K, Grundmann RT, Behrendt C-A. Gender differences in endovascular treatment of infrainguinal peripheral artery disease. Vasa. 2017;46(4):296-303.

- Roumia M, Aronow HD, Soukas P, et al. Sex differences in disease-specific health status measures in patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease: Data from the PORTRAIT study. Vascular Medicine. 2017;22(2):103-109.

- Soden PA, Zettervall SL, Shean KE, et al. Regional variation in outcomes for lower extremity vascular disease in the Vascular Quality Initiative. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2017;66(3):810-818.

- Raja A, Wadhera RK, Choi E, et al. Association of Clinical Setting With Sociodemographics and Outcomes Following Endovascular Femoropopliteal Artery Revascularization in the United States. Circulation Cardiovascular Quality & Outcomes. 2023;16(1):e009199.

- Vilariño-Rico J, Fariña-Casanova X, Martínez-Gallego EL, et al. The Influence of the Socioeconomic Status and the Density of the Population on the Outcome After Peripheral Artery Disease. Annals of Vascular Surgery. 2023;89:269-279.

- Rizzo JA, Chen J, Laurich C, et al. Racial Disparities in PAD-Related Amputation Rates among Native Americans and non-Hispanic Whites: An HCUP Analysis. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(2):782-800.

- Hirsch AT, Allison MA, Gomes AS, et al. A call to action: women and peripheral artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(11):1449-1472.

- Hiramoto JS, Katz R, Ix JH, et al. Sex differences in the prevalence and clinical outcomes of subclinical peripheral artery disease in the Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) study. Vascular. 2014;22(2):142-148.

- Jelani QU, Mena-Hurtado C, Burg M, et al. Relationship Between Depressive Symptoms and Health Status in Peripheral Artery Disease: Role of Sex Differences. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(16):e014583.

- Thomas M, Patel KK, Gosch K, et al. Mental health concerns in patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease: Insights from the PORTRAIT registry. J Psychosom Res. 2020;131:109963.

- Collins TC, Suarez-Almazor M, Bush RL, Petersen NJ. Gender and peripheral arterial disease. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2006;19(2):132-140.

- McDermott MM, Greenland P, Liu K, et al. Sex differences in peripheral arterial disease: leg symptoms and physical functioning. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(2):222-228.

- Enzler M, Ruoss M, Seifert B, Berger M. The influence of gender on the outcome of arterial procedures in the lower extremity. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 1996;11(4):446-452.

- Nguyen LL, Hevelone N, Rogers SO, et al. Disparity in outcomes of surgical revascularization for limb salvage: race and gender are synergistic determinants of vein graft failure and limb loss. Circulation. 2009;119(1):123-130.

- Javed Z, Haisum Maqsood M, Yahya T, et al. Race, racism, and cardiovascular health: Applying a social determinants of health framework to racial/ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2022;15(1):e007917.

- Hackler EL, Hamburg NM, White Solaru KT. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Peripheral Artery Disease. Circulation Research. 2021;128(12):1913-1926.

- Allison MA, Ho E, Denenberg JO, et al. Ethnic-specific prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4):328-333.

- Matsushita K, Sang Y, Ning H, et al. Lifetime Risk of Lower-Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease Defined by Ankle-Brachial Index in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(18):e012177.

- Alasaad M, Zaitoun A, Szpunar S, et al. Association of Race with Long-Term Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Popliteal and Infra-Popliteal Percutaneous Peripheral Arterial Interventions. Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine. 2019;20(8):649-653.

- Demsas F, Joiner MM, Telma K, Flores AM, Teklu S, Ross EG. Disparities in peripheral artery disease care: A review and call for action. Semin Vasc Surg. 2022;35(2):141-154.

- Allison MA, Gonzalez F, 2nd, Raij L, et al. Cuban Americans have the highest rates of peripheral arterial disease in diverse Hispanic/Latino communities. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2015;62(3):665-672.

- Chen L, Zhang D, Shi L, Kalbaugh CA. Disparities in Peripheral Artery Disease Hospitalizations Identified Among Understudied Race-Ethnicity Groups. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:692236.

- Hong MS, Beck AW, Nelson PR. Emerging national trends in the management and outcomes of lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. Annals of Vascular Surgery. 2011;25(1):44-54.

- Aboyans V, Ricco J-B, Bartelink M-L, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Kardiologia Polska (Polish Heart Journal). 2017;75(11):1065-1160.

- Schramm K, Rochon PJ. Gender differences in peripheral vascular disease. Paper presented at: Seminars in interventional radiology2018.

- Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Patients With Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135(12):e686-e725.

- Treat-Jacobson D, McDermott MM, Bronas UG, et al. Optimal Exercise Programs for Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(4):e10-e33.

- Committee CS. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). CAPRIE Steering Committee. Lancet. 1996;348(9038):1329-1339.

- Anand SS, Bosch J, Eikelboom JW, et al. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in patients with stable peripheral or carotid artery disease: an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10117):219-229.

- Bonaca MP, Bauersachs RM, Anand SS, et al. Rivaroxaban in Peripheral Artery Disease after Revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1994-2004.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ AGS/APhA/ASH/ ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1269-1324.

- Low Wang CC, Blomster JI, Heizer G, et al. Cardiovascular and Limb Outcomes in Patients With Diabetes and Peripheral Artery Disease: The EUCLID Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(25):3274-3284.

- Belch JJF, Brodmann M, Baumgartner I, et al. Lipid-lowering and anti-thrombotic therapy in patients with peripheral arterial disease: European Atherosclerosis Society/European Society of Vascular Medicine Joint Statement. Atherosclerosis. 2021;338:55-63.

- Conte MS, Bradbury AW, Kolh P, et al. Global vascular guidelines on the management of chronic limb-threatening ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69(6S):3S-125S e140.

Clinical Topics: Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia, Vascular Medicine, Atherosclerotic Disease (CAD/PAD)

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Cardiovascular Diseases, Plaque, Atherosclerotic, Peripheral Arterial Disease, Dyslipidemias, Socioeconomic Factors

< Back to Listings