Exercise Therapy in Symptomatic Peripheral Artery Disease: Summary of Current Knowledge and Future Directions

Quick Takes

- Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that supervised exercise therapy improves functional status, walking performance, and quality of life in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) and claudication. This therapy is recommended as initial treatment or as an adjunct following revascularization.

- Structured, community-based exercise programs that implement closely monitored exercise regimens have been shown to improve walking performance in patients with PAD and claudication.

- Despite evidence of significant benefits of exercise therapy in PAD, it remains underutilized due to gaps in patient and provider awareness, limited accessibility and affordability of programs, and a scarcity of effective, community-based interventions. Current guidelines emphasize the need for further research and systemic solutions to overcome these barriers and enhance implementation.

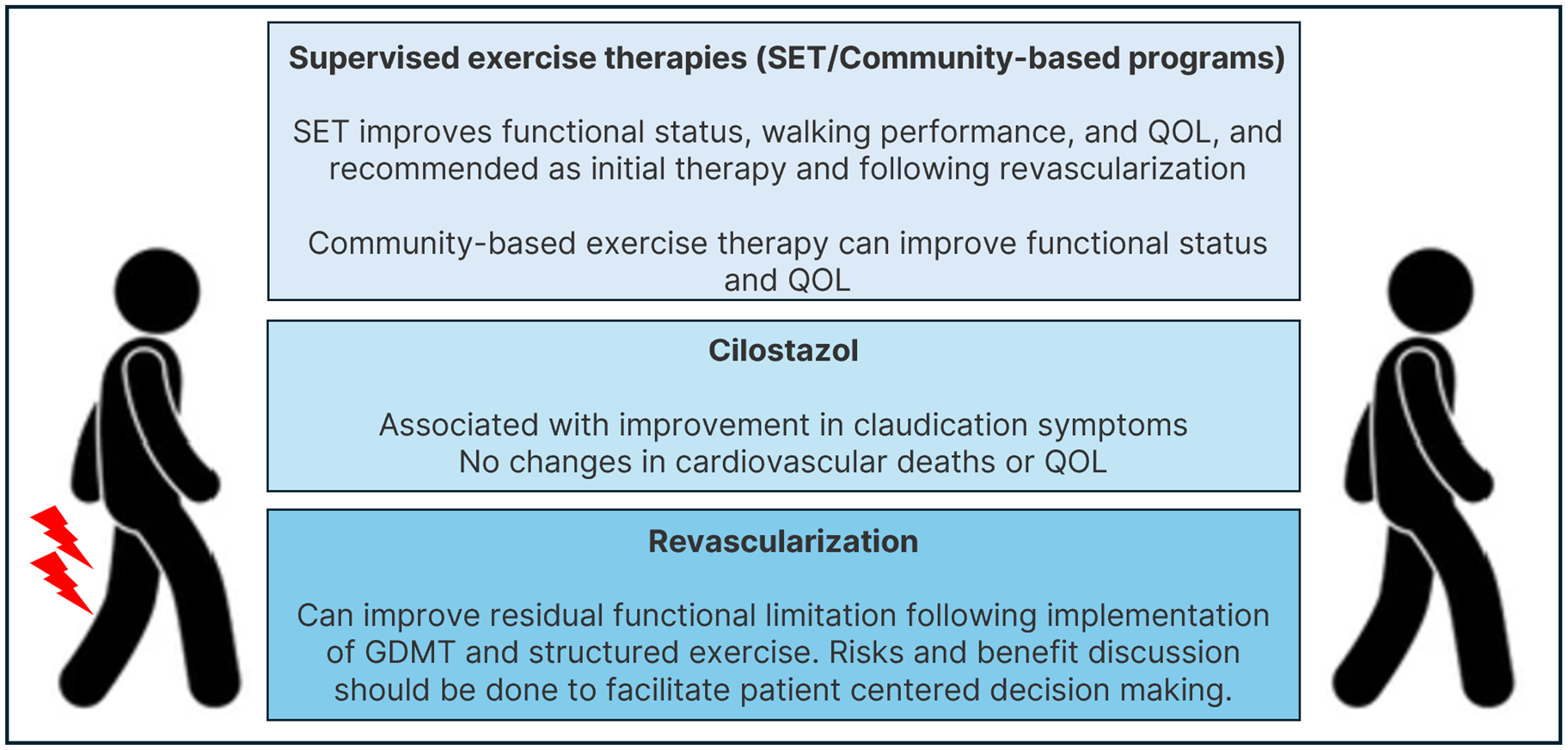

Symptomatic peripheral artery disease (PAD) is increasingly prevalent worldwide and most patients have significant functional impairment even at early stages of disease. Symptomatic PAD manifests as exercise-induced, lower-extremity discomfort, including fatigue, aching, or pain. Claudication, defined as reproducible lower-extremity muscle pain precipitated by walking and relieved with rest, is a specific subset of symptomatic PAD. However, typical claudication is not a common presentation. Symptomatic PAD is caused by a limitation in blood flow leading to ischemia to these muscles during activity1 and can often lead to significant functional limitation and decreased overall quality of life (QOL).2 In addition to cardiovascular risk factor modification by aggressive medical management to reduce major adverse cardiovascular and limb events in patients with PAD, improving functional performance and QOL in symptomatic patients are goals of treatment. Recommended therapies include supervised exercise therapy programs, cilostazol, and peripheral revascularization (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Therapies for Functional Limitation and Claudication in PAD

GDMT = guideline-directed medical therapy; PAD = peripheral artery disease; QOL = quality of life; SET = supervised exercise therapies.

Structured exercise programs have been shown to improve walking performance, functional status, and QOL in patients with symptomatic PAD. Approaches that have been studied include structured exercise therapy (SET) and community-based exercise programs. Exercise treatment focuses mainly on walking, although other types of exercise have been studied as well. SET is an exercise program that is directly supervised by a clinician or advanced practice provider and usually implemented by a clinical exercise physiologist or a nurse. Training usually involves walking to moderate to maximum tolerable pain alternating with rest. Sessions typically last 60 min and are held three times a week for 12 weeks. SET can be delivered in a clinic office space or hospital, although cardiac rehabilitation programs are considered an ideal setting. Structured, community-based exercise programs include structured exercise plans similar to SET which take place in a community or home-based settings. These programs are prescribed by a health care professional and are self-directed with as-needed guidance.1

The recent PAD guidelines1,3 recommend SET as first-line treatment for patients with PAD and functional-related symptoms. This expert analysis aims to review the current evidence, future research, and implementation of exercise therapy for patients with symptomatic PAD.

High-quality evidence is available for SET as an initial treatment for claudication with consistent results in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). A meta-analysis of 15 RCTs demonstrated improvement in walking distance in a 6-min walk test (6MWT) or a graded treadmill test following SET.4 The CLEVER (Claudication: Exercise Versus Endoluminal Revascularization) trial compared optimal medical care (OMC) alone with OMC with SET or revascularization with arterial stenting in 111 patients with aortoiliac PAD and showed improvement in peak walking time in patients in both revascularization and SET groups compared with OMC alone at 6-months and 18-months following randomization. QOL was improved in both SET and revascularization groups compared with OMC, with evidence of improvement in QOL measures in the revascularization group compared with SET.5 A meta-analysis of 10 RCTs included 1,087 patients and compared endovascular revascularization with alternative management strategies for PAD with claudication and showed comparable improvement in walking distance and QOL measures between revascularization and SET compared with OMC.6 Supported by its favorable benefit–risk ratio, the recent PAD guidelines recommend SET as an initial treatment for PAD with claudication.1

SET was also shown to be beneficial in patients with PAD and functional limitation following lower extremity revascularization. The ERASE (Endovascular Revascularization And Supervised Exercise for claudication) trial randomized 212 patients with PAD and claudication to either endovascular revascularization and SET or SET alone and showed greater improvements in functional status and QOL measures in patients randomized to revascularization and SET combination therapy.7 This data was supported by a meta-analysis of randomized trials6,8 and recent guidelines.1,3,9

For patients that are limited in walking and cannot participate in walking-based SET, nonwalking SET programs have been studied and have included arm ergometry, recumbent stepping, and resistance training. While there is evidence to suggest functional improvement with these modes of exercise, additional data from adequately powered randomized trials is still needed.1,4

Despite this evidence, guideline recommendations, and insurance coverage of SET by Medicare programs since 2017, SET implementation is far from optimal. Currently, Medicare and most commercial insurance companies cover SET (usually 36 sessions in a period of 12 weeks) for patients with claudication. Notably, if patients continue to be symptomatic, coverage can be extended to an additional 36 sessions over a subsequent 12-week period. However, low rates of referrals, limited access, and high rate of patient nonadherence due to time commitments and copayment costs remain as major barriers.1,10,11

Structured, community-based exercise programs can help address the lack of accessibility to SET that hinders its implementation. Evidence of the efficacy of these programs is accumulating. The GOALS (Group Oriented Arterial Leg Study) included patients with PAD, both with and without claudication, and demonstrated improvement in 6-min walking distance, maximal walking treadmill time, and patient reported parameters of the Walking Impairment Questionnaire (WIQ) with community based exercise program.12 The LITE (Low Intensity Exercise Intervention in PAD) trial randomized 305 patients with PAD and claudication symptoms to high-intensity versus low-intensity community-based structured exercise with weekly virtual coaching and to a nonexercise control group, which received weekly educational telephone calls. In this study, only the high-intensity community-based walking program combined with virtual coaching led to significant improvements in the 6MWT compared with the control group. However, at 6 months, greater improvement in WIQ scores was seen in patients randomized to the low-intensity exercise group compared with high-intensity.13 The latter study suggest that there might be a paradox in community-based exercise therapy for patients with PAD and functional limitation: patients who walk through pain often gain functional benefits but not QOL improvements, while those who avoid pain may see better QOL but worse functional outcomes. Discussion with patients about the possible functional benefits and potential effect of pain during exercise on QOL is essential to reach a patient-centered decision. Some patients may prioritize function despite discomfort, while others may prefer pain-free options focusing on QOL. Personalizing exercise programs and regularly reassessing patient experiences can optimize adherence and outcomes in PAD management.

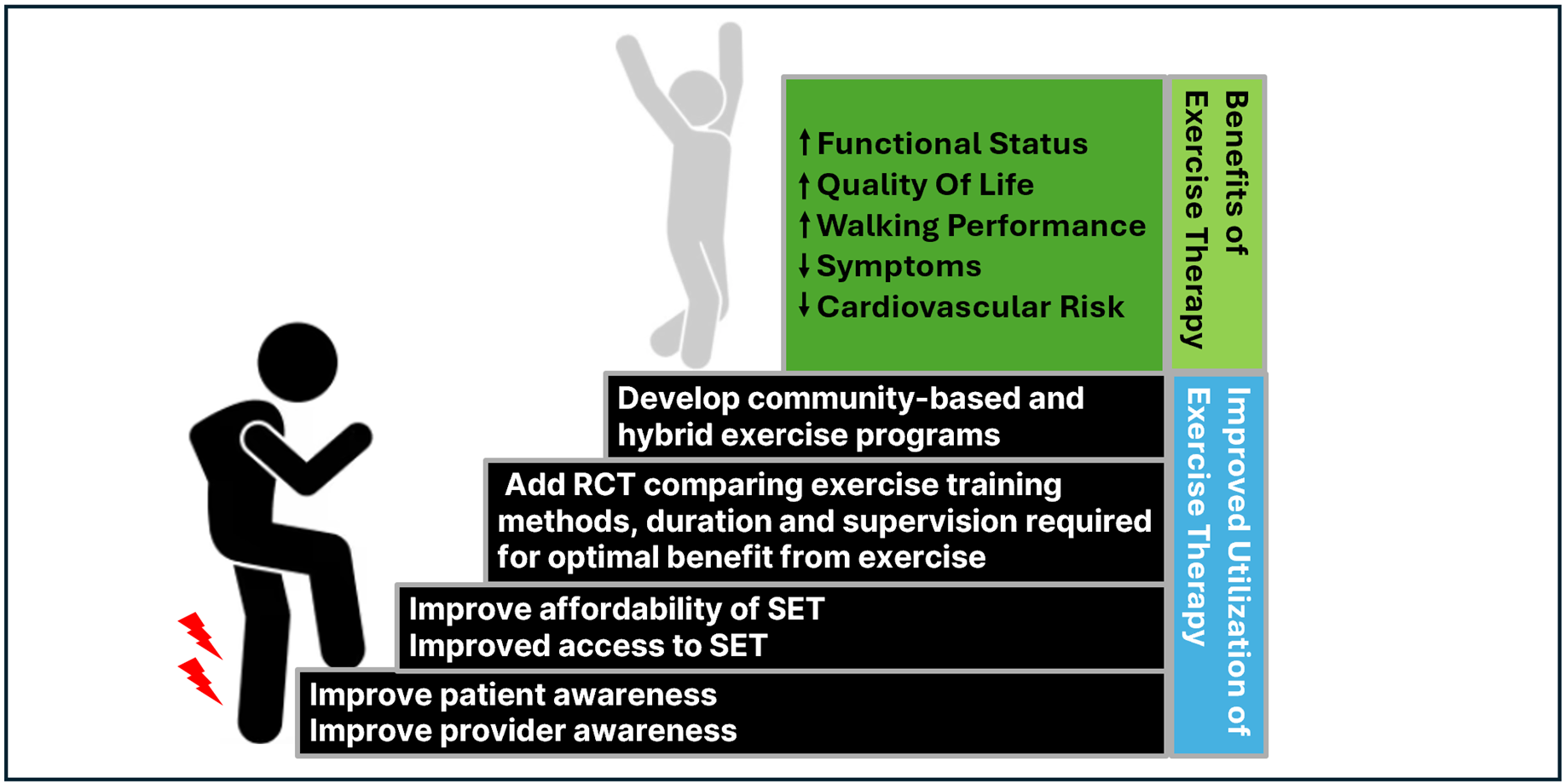

In conclusion, randomized data suggest that SET can improve pain and maximal walking distance as initial treatment and in addition to revascularization in patients with PAD and claudication symptoms. Effective community-based exercise interventions can potentially promote long-term behavioral change and overcome barriers to utilization of supervised exercise programs. However, further work is still needed to address the existing barriers to exercise treatment for symptomatic PAD, including improving supervised exercise program accessibility, optimizing home-based exercise interventions and monitoring, improving evidence-based data and consistency between different home-based exercise programs, and improving integration and implementation of exercise therapy in PAD management (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Barriers for Exercise Therapies in PAD

PAD = peripheral artery disease; RCT= randomized controlled trial; SET= supervised exercise therapy.

References

- Gornik HL, Aronow HD, Goodney PP, et al.; Peer Review Committee Members. 2024 ACC/AHA/AACVPR/APMA/ABC/SCAI/SVM/SVN/SVS/SIR/VESS guideline for the management of lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2024;149:e1313-e1410.

- Treat-Jacobson D, McDermott MM, Bronas UG, et al.; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Optimal exercise programs for patients with peripheral artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;139:e10-e33.

- Mazzolai L, Teixido-Tura G, Lanzi S, et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of peripheral arterial and aortic diseases. Eur Heart J 2024;45:3538-700.

- Parmenter BJ, Dieberg G, Smart NA. Exercise training for management of peripheral arterial disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 2015;45:231-44.

- Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, Regensteiner JG, et al. Supervised exercise, stent revascularization, or medical therapy for claudication due to aortoiliac peripheral artery disease: the CLEVER study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:999-1009.

- Fakhry F, Fokkenrood HJ, Spronk S, Teijink JA, Rouwet EV, Hunink MGM. Endovascular revascularisation versus conservative management for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;3:CD010512.

- Fakhry F, Spronk S, van der Laan L, et al. Endovascular revascularization and supervised exercise for peripheral artery disease and intermittent claudication: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;314:1936-44.

- Saratzis A, Paraskevopoulos I, Patel S, et al. Supervised exercise therapy and revascularization for intermittent claudication: network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2019;12:1125-36.

- Mazzolai L, Belch J, Venermo M, et al. Exercise therapy for chronic symptomatic peripheral artery disease: a clinical consensus document of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Aorta and Peripheral Vascular Diseases in collaboration with the European Society of Vascular Medicine and the European Society for Vascular Surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2024;Feb 16:[ePub ahead of print].

- Polonsky TS, McDermott MM. Lower extremity peripheral artery disease without chronic limb-threatening ischemia: a review. JAMA 2021;325:2188-98.

- Divakaran S, Li S, Song Y, Krawisz AK, Carroll BJ, Secemsky EA. Underutilization of supervised exercise therapy for symptomatic peripheral artery disease among Medicare beneficiaries. Vasc Med 2024;29:559-60.

- McDermott MM, Liu K, Guralnik JM, et al. Home-based walking exercise intervention in peripheral artery disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;310:57-65.

- McDermott MM, Spring B, Tian L, et al. Effect of low-intensity vs high-intensity home-based walking exercise on walk distance in patients with peripheral artery disease: the LITE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021;325:1266-76.

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, Prevention, Vascular Medicine, Atherosclerotic Disease (CAD/PAD), Exercise

Keywords: Peripheral Arterial Disease, Exercise Therapy, Intermittent Claudication