AHA Scientific Statement Update on Kawasaki Disease: Identifying and Managing Patients at High Risk

Quick Takes

- Patients with Kawasaki disease (KD) at increased risk for developing coronary artery aneurysms (CAA) (particularly those ≤6 months old or with baseline coronary artery z-scores ≥2.5) require close monitoring and intensification of primary therapy, and frequent inpatient echocardiograms among patients with CAA remain important in the determination of additional therapy and outpatient follow-up timing.

- Direct oral anticoagulants are a recent alternative to warfarin or low–molecular-weight heparin for patients with KD with giant CAA requiring anticoagulation.

- Clinicians caring for patients with KD must proactively develop a collaborative team approach to prepare for major adverse cardiac events and to provide long-term surveillance, especially for patients with giant CAA.

There have been significant advances in the understanding of Kawasaki disease (KD) since the first published report in 1967. The recently published 2024 American Heart Association scientific statement1 reviews the latest evidence and expert consensus since the prior version in 2017 while addressing two specific questions: 1) How are patients at high risk identified and treated before coronary artery aneurysms (CAA) develop?; and 2) How can adverse outcomes in patients with CAA be avoided?

Identifying and Treating Patients at High Risk Before CAA Develop

The diagnostic criteria for KD have not changed, but the authors emphasize the importance of early diagnosis and identification of patients at high risk. The statement acknowledges the diagnostic challenges, particularly with the inclusion of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in the differential diagnosis since 2020.2 Although there are several Japanese scoring systems for predicting intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) resistance, which is associated with CAA development, these systems have not performed well in North American cohorts. This statement reviews the recent criteria developed for the North American population, comprising baseline left anterior descending (LAD) or right coronary artery (RCA) z-score ≥2, age <6 months, Asian race, or C-reactive protein ≥13 mg/dL.3 Patients deemed high-risk in this scoring system have a 16-fold increased likelihood of CAA development. Studies from Japan4 and North America5 have also shown that infants <12 months of age are at increased risk of developing CAA. Based on data across multiple racial and ethnic groups, the 2024 statement defines high-risk as age ≤6 months or z-score ≥2.5 in the LAD or RCA.

Transthoracic echocardiography remains the primary imaging modality in acute KD, and patients at high risk require frequent assessments. The authors discuss the challenges though in assessing coronary arteries. Several z-score systems exist, reflecting different normative values in patient populations and various methodologies, and z-score evaluations require precise measurements and consistency to reach valid conclusions. Even if the initial echocardiogram is normal, the authors advocate for repeating the study 2-3 days later. Rather than the 2017 statement's recommended outpatient follow-up of 1-2 weeks, the 2024 statement suggests follow-up in 1 week, emphasizing the risk of CAA development in patients at high risk.

KD management requires identification of patients at high risk for potential primary-therapy intensification. The 2017 statement discussed consideration of corticosteroids or infliximab as primary adjunctive therapy to IVIG for patients at high risk, yet without a clear high-risk definition beyond the Japanese population. The 2024 statement discusses additional options, including available dosing and efficacy data for corticosteroids and infliximab, along with limited data for anakinra and cyclosporine. Perhaps the precise selection of which adjunctive therapy, whether corticosteroids or infliximab, is less important than selecting either agent, as both therapies decrease progression in CAA size compared with IVIG alone.6 Similarly, the therapeutic options for IVIG resistance have expanded. Previously, the primary options were a second dose of IVIG, corticosteroids, or infliximab, and the current statement provides additional safety and dosing data for these medications, including the KIDCARE (Kawasaki Disease Comparative Effectiveness) study for infliximab,7 along with etanercept, anakinra, and cyclosporine.

Avoiding Adverse Outcomes in Patients With CAA

Patients with giant CAA are at the highest risk for morbidity and mortality. Even if the luminal diameter decreases in size, regression occurs via layering thrombus or luminal myofibroblastic proliferation, leading to ongoing ischemic risks. Traditionally, patients with giant CAA have been treated with antiplatelet therapy along with anticoagulation, such as warfarin or low–molecular-weight heparin. The latest statement highlights direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) as an alternative for anticoagulation with similar effectiveness, decreased monitoring requirements, fewer drug and food interactions, and oral formulations.8

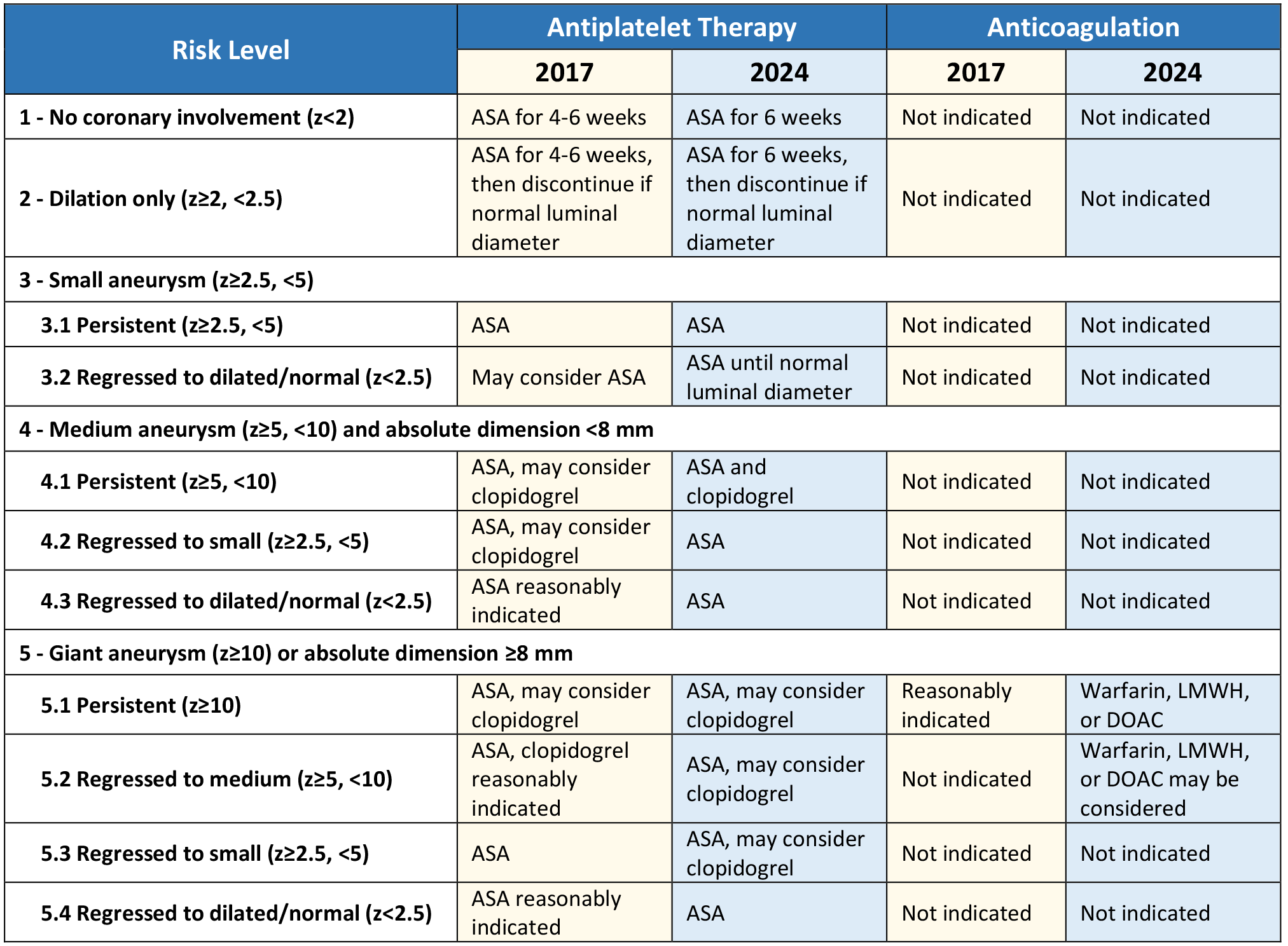

Previously, anticoagulation was recommended for patients with giant CAA, then only antiplatelet therapy if the luminal diameter regressed to medium in size. The 2024 statement recommends considering anticoagulation even if the luminal diameter regresses to medium, particularly if the regression was secondary to thrombosis (Table 1). This change reflects the recent data highlighting the risks of thrombosis with giant CAA and will require centers to discuss with their patients and consider medication adjustments with KD experts for the optimal thromboprophylaxis regimen.9

Table 1: Updates in Thromboprophylaxis for Kawasaki Disease

ASA = aspirin; DOAC = direct oral anticoagulant; LMWH = low–molecular-weight heparin; z = z-score.

Although the risk of myocardial infarction (MI) is highest in the first 2-3 months after illness, patients with CAA (almost exclusively giant CAA) are at ongoing risk. This statement provides a detailed algorithm for MI management. To prepare for these emergencies and the inevitable presentation of an MI, multidisciplinary teams must be proactively created given the rarity of MIs in pediatric populations and the frequently nonspecific presenting symptoms that distinguish pediatric MIs from adults with atherosclerosis.

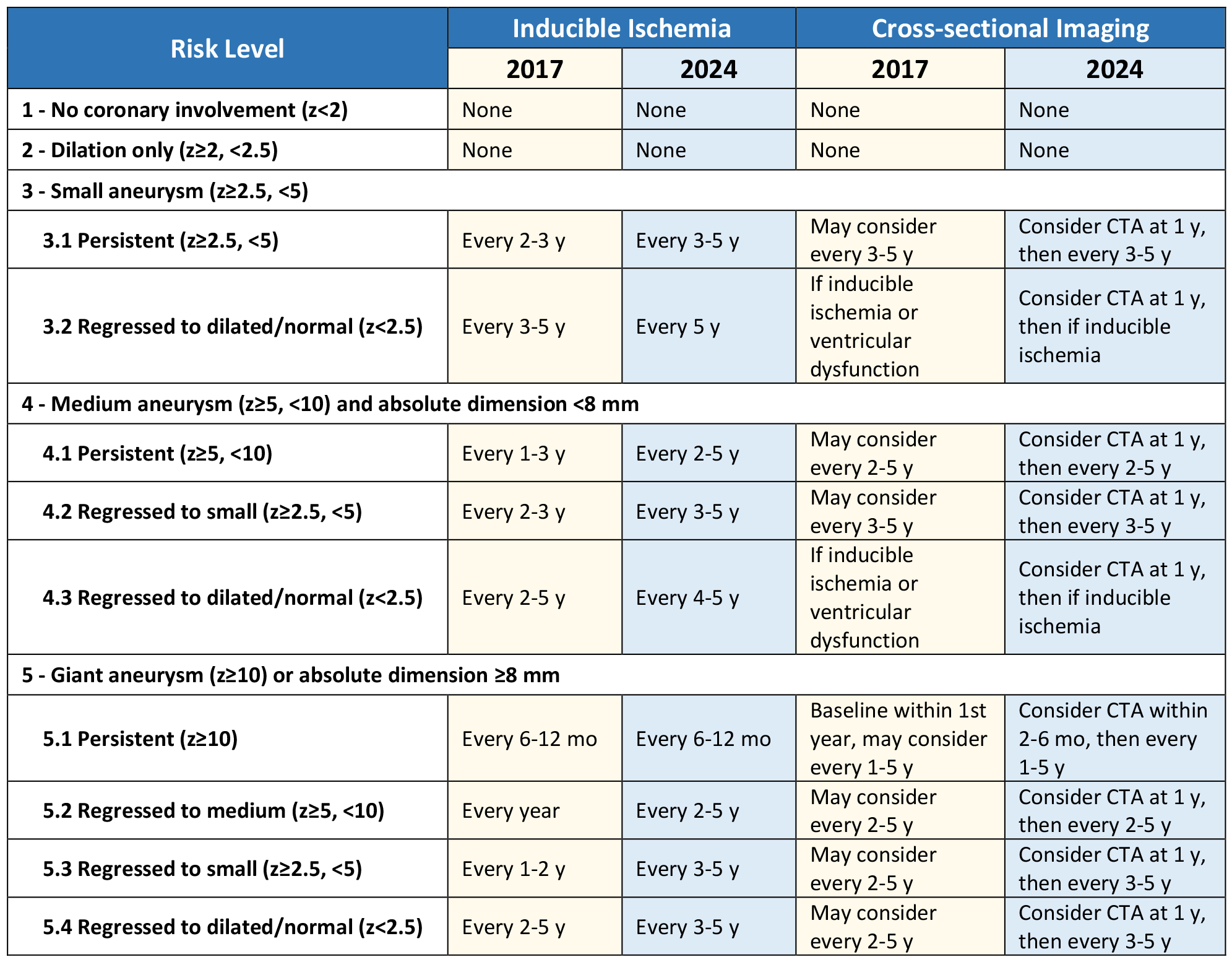

Since the 2017 statement, there have been multiple studies emphasizing the increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events among patients with giant CAA, with far less risk in smaller CAA.9,10 Accordingly, the 2024 statement provides updated guidance for surveillance imaging, both for detailed anatomic assessment and for inducible ischemia (Table 2). Computed tomography angiography provides detailed anatomic assessment and can be considered 1 year after illness as a baseline in patients with CAA. Test selection for inducible ischemia depends on the patient's age and each center's experience and expertise in performing and interpreting these tests. The statement highlights several options: stress echocardiography (exercise or pharmacologic), stress cardiac magnetic resonance, positron emission tomography, or nuclear medicine myocardial perfusion.

Table 2: Updates in Long-Term Surveillance of Kawasaki Disease

CTA = computed tomography angiography; mo = month; y = year; z = z-score.

Conclusion

This statement is a call to action in the KD community. For those caring for patients with KD, it is essential to identify and treat those at high risk, to plan for when (not if) they present with emergencies, to develop long-term protocols, and to collaborate with adult cardiology for transition of care. The 2024 statement discusses future research directions, and through such clinical and research collaboration, collective knowledge gaps will continue to be filled in and the understanding of KD will be expanded further.

References

- Jone PN, Tremoulet A, Choueiter N, et al.; American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Lifelong Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; and Council on Clinical Cardiology. Update on diagnosis and management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024;150:e481-e500.

- Harahsheh AS, Shah S, Dallaire F, et al.; International Kawasaki Disease Registry (IKDR). Kawasaki Disease in the time of COVID-19 and MIS-C: the International Kawasaki Disease Registry. Can J Cardiol 2024;40:58-72.

- Son MBF, Gauvreau K, Tremoulet AH, et al. Risk model development and validation for prediction of coronary artery aneurysms in Kawasaki disease in a North American population. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:[ePub ahead of print].

- Fukazawa R, Kobayashi J, Ayusawa M, et al.; Japanese Circulation Society Joint Working Group. JCS/JSCS 2020 guideline on diagnosis and management of cardiovascular sequelae in Kawasaki disease. Circ J 2020;84:1348-407.

- Cameron SA, Carr M, Pahl E, DeMarais N, Shulman ST, Rowley AH. Coronary artery aneurysms are more severe in infants than in older children with Kawasaki disease. Arch Dis Child 2019;104:451-5.

- Dionne A, Burns JC, Dahdah N, et al. Treatment intensification in patients with Kawasaki disease and coronary aneurysm at diagnosis. Pediatrics 2019;143:[ePub ahead of print].

- Burns JC, Roberts SC, Tremoulet AH, et al.; KIDCARE Multicenter Study Group. Infliximab versus second intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of resistant Kawasaki disease in the USA (KIDCARE): a randomised, multicentre comparative effectiveness trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2021;5:852-61.

- Portman MA, Jacobs JP, Newburger JW, et al.; ENNOBLE-ATE Trial Investigators. Edoxaban for thromboembolism prevention in pediatric patients with cardiac disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;80:2301-10.

- McCrindle BW, Manlhiot C, Newburger JW, et al.; International Kawasaki Disease Registry. Medium-term complications associated with coronary artery aneurysms after Kawasaki disease: a study from the International Kawasaki Disease Registry. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:[ePub ahead of print].

- Elias MD, Brothers JA, Hogarty AN, et al. Outcomes associated with giant coronary artery aneurysms after Kawasaki disease: a single-center United States experience. J Pediatr 2024;274:[ePub ahead of print].

Clinical Topics: Stable Ischemic Heart Disease, Vascular Medicine, Chronic Angina, Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology

Keywords: American Heart Association, Coronary Aneurysm