Athletes' Role in Reducing Sudden Cardiac Death

Merije Chukumerije, MD, FACC

Although rare, a sports-related sudden cardiac arrest (SrSCA) and/or sudden cardiac death (SCD) in an athlete is a devastating, heartbreaking event with significant emotional and societal impact. Male athletes appear to have an incidence of SCD up to fivefold higher than their female counterparts,2 more than observed in the general population.3 There is also clear evidence demonstrating an increased risk with higher level of competition, particularly from high school to collegiate athletics as first studied by Van Camp et al.2 Data from the National Collegiate Athletic Association has shown higher event rates in Division I athletes compared to Division II and III athletes,4,5 and also highlighted that amongst the most at-risk of all athletes were Black male Division I basketball players.4,5

Given the growing pool of data, prudent efforts focusing on education and prevention have been implemented over the past decade, such as preparticipation screening of athletes to identify clinically relevant preexisting cardiovascular conditions. Although controversial and without universal standardization, this screening typically includes a comprehensive history and physical examination with the addition of downstream cardiovascular testing, if necessary. The presence of high-risk findings allows the clinician to appropriately counsel the athlete and their family, coach, team and organization regarding management or potential disqualification from play.

Emergency Action Plan

Recognizing that SrSCA may still occur despite our best efforts at prevention via screening, training facilities, sporting venues, and schools are encouraged to publish and prepare an emergency action plan (EAP) for the unfortunate moment when it is needed. There are multiple parts to an effective plan. The American Heart Association (AHA) has underscored a chain of survival which emphasizes an immediate recognition of the SCA, activation of emergency medical services, early cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), rapid automated external defibrillator (AED) use, adequate advanced cardiac life support, and appropriate post-cardiac arrest care.10 The effectiveness of all parts of the EAP is only as good as the knowledge, understanding, and ability of those tasked with implementing it. For this reason, athletic trainers and team medical personnel, including team physicians, have been intimately apprised to the resuscitation strategy and frequently recertify to validate their competency. But what about the most important members of the response team? The athlete.

The Athlete's Role

As the hard-to-watch videos often illustrate, typically the first and closest witnesses to a fallen player are their fellow athletes. Understandably, the initial reaction is often one of fear, shock and dismay; rarely one of action. But the ability to quickly recognize a fallen player, check for a pulse, and immediately start CPR before and during the arrival of the trained staff may be a crucial addition to a successful resuscitation. Multiple studies demonstrate that immediate resuscitation efforts with CPR and early defibrillation with an AED significantly improve the chance of survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, with survival rates declining by 7% to 10% for every minute that defibrillation is delayed.11-13 As such, the athletic training team and medical personnel should have immediate access to AEDs, and participating athletes and spectators should also be aware of the locations of these devices and how to use them.

The world saw the perfect example of this at the 2020 UEFA European Football Championship Soccer tournament when a teammate provided immediate CPR to a fallen player. This was further supported in a French study that demonstrated how major improvements in on-field resuscitation led to a 3-fold increase in survival.18

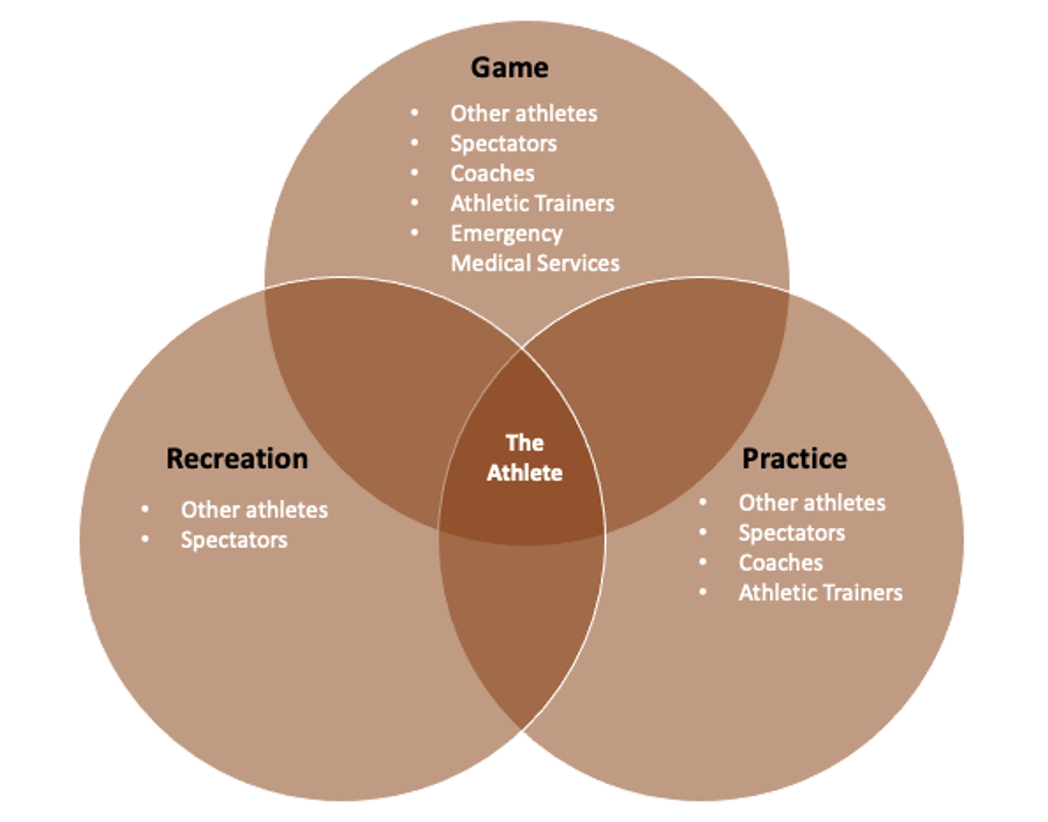

As the common denominator and central figure in sports, the athlete may also play a significant role in sporting events that occur away from formal play. Organized sporting events have on-site emergency teams trained and prepared to implement a rehearsed EAP during games, dramatically reducing the SCA mortality rate.11-15 However, there is limited data highlighting the incidence of SrSCA when not in the presence of trained medical professionals (i.e., when the athletes are training only amongst themselves). As practice and reactional play occur more frequently than formal games, increasing opportunities for cardiac events to occur, it is essential athletes understand the basics of SCD and how to implement an EAP. For this reason, athletes should consider practicing SCA resuscitation alongside other drills. Furthermore, given the rate of SCD in the general population, athletes equipped with CPR and emergency cardiovascular care are valuable members to their community and family. There are many ways to encourage the athlete to embrace this new responsibility, all of which starts with education, especially given the efforts to simplify CPR.9

Conclusion

Despite advances in screening and preparation, SCD – though extremely rare – will continue to occur. As we continue to learn more about SCD in athletes, provide more effective preparticipation screening, and improve response plans, an all-hands-on-deck approach is necessary to prevent every causality possible, both in the presence and absence of the medical staff. Training athletes to recognize and immediately respond to a witnessed collapse by a fellow athlete or spectator may be the one play in the playbook they will forever remember.

References

- Harmon KG, Drezner JA, Wilson MG, Sharma S. Incidence of sudden cardiac death in athletes: a state-of-the-art review. Br J Sports Med. 2014 Aug;48(15):1185–92.

- Van Camp S.P., Bloor C.M., Mueller F.O., Cantu R.C. and Olson H.G. : "Nontraumatic sports death in high school and college athletes". Med Sci Sports Exerc 1995; 27: 641.

- Kannel WB, Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Cobb J. Sudden coronary death in women. Am Heart J. 1998 Aug;136(2):205-12. doi: 10.1053/hj.1998.v136.90226. PMID: 9704680.

- Emery MS, Kovacs RJ. Sudden Cardiac Death in Athletes. JACC Heart Fail. 2018 Jan;6(1):30-40. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.07.014. PMID: 29284578.

- Harmon KG, Asif IM, Maleszewski JJ et al. Incidence, Cause, and Comparative Frequency of Sudden Cardiac Death in National Collegiate Athletic Association Athletes: A Decade in Review. Circulation. 2015 Jul 7;132(1):10–9

- Corrado D, Basso C, Pavei A, Michieli P, Schiavon M, Thiene G. Trends in sudden cardiovascular death in young competitive athletes after implementation of a preparticipation screening program. JAMA. 2006 Oct 4;296(13):1593-601. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.13.1593. PMID: 17018804.

- Petek BJ, Baggish AL. Current controversies in pre-participation cardiovascular screening for young competitive athletes. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2020 Jul;18(7):435-442. doi: 10.1080/14779072.2020.1787154. Epub 2020 Jul 7. PMID: 32594825.

- Harmon K.G., Zigman M. and Drezner J.A. : "The effectiveness of screening history, physical exam, and ECG to detect potentially lethal cardiac disorders in athletes: a systematic review/meta-analysis". J Electrocardiol 2015; 48: 329.

- Drezner JA, Sharma S, Baggish A, Papadakis M, Wilson MG, Prutkin JM, Gerche A, Ackerman MJ, Borjesson M, Salerno JC, Asif IM, Owens DS, Chung EH, Emery MS, Froelicher VF, Heidbuchel H, Adamuz C, Asplund CA, Cohen G, Harmon KG, Marek JC, Molossi S, Niebauer J, Pelto HF, Perez MV, Riding NR, Saarel T, Schmied CM, Shipon DM, Stein R, Vetter VL, Pelliccia A, Corrado D. International criteria for electrocardiographic interpretation in athletes: Consensus statement. Br J Sports Med. 2017 May;51(9):704-731. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097331. Epub 2017 Mar 3. PMID: 28258178.

- Field J.M., Hazinski M.F., Sayre M.R., Chameides L., Schexnayder S.M., Hemphill R., Samson R.A., Kattwinkel J., Berg R.A., Bhanji F., Cave D.M., Jauch E.C., Kudenchuk P.J., Neumar R.W., Peberdy M.A., Perlman J.M., Sinz E., Travers A.H., Berg M.D., Billi J.E., Eigel B., Hickey R.W., Kleinman M.E., Link M.S., Morrison L.J., O'Connor R.E., Shuster M., Callaway C.W., Cucchiara B., Ferguson J.D., Rea T.D. and Vanden Hoek T.L. : "Part 1: executive summary: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care". Circulation 2010; 122: S640.

- Rothmier JD, Drezner JA. The Role of Automated External Defibrillators in Athletics. Sports Health. 2009;1(1):16-20.

- Drezner JA. Practical guidelines for automated external defibrillators in the athletic setting. Clin J Sport Med. 2005 Sep;15(5):367-9. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000179231.33132.8a. PMID: 16162998.

- Drezner JA, Courson RW, Roberts WO, Mosesso VN, Link MS, Maron BJ. Inter-association Task Force recommendations on emergency preparedness and management of sudden cardiac arrest in high school and college athletic programs: a consensus statement. J Athl Train. 2007;42(1):143-158.

- Larsen MP, Eisenberg MS, Cummins RO, Hallstrom AP. Predicting survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a graphic model. Ann Emerg Med. 1993 Nov;22(11):1652-8. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81302-2. PMID: 8214853.

- Valenzuela TD, Roe DJ, Cretin S, Spaite DW, Larsen MP. Estimating effectiveness of cardiac arrest interventions: a logistic regression survival model. Circulation. 1997;96:3308–3313

- Hainline B, Drezner J, Baggish A, et al. Interassociation Consensus Statement on Cardiovascular Care of College Student-Athletes. J Athl Train. 2016;51(4):344-357. doi:10.4085/j.jacc.2016.03.527

- Zheng ZJ, Croft JB, Giles WH, Mensah GA. Sudden cardiac death in the United States, 1989 to 1998. Circulation. 2001 Oct 30;104(18):2158-63. doi: 10.1161/hc4301.098254. PMID: 11684624.

- Karam N et al. Evoluation of Incidence, Management, and Outcomes Over Time In Sports-related Sudden Cardiac Arrest. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Jan, 79 (3) 238–246

This article was authored by Merije Chukumerije, MD, FACC, member of ACC's Sports and Exercise Section.

Additional ACC SCA resources include:

- ACC Joins Smart Heart Sports Coalition to Support Nationwide CPR Education, AED Access

- CardioSmart Patient Hub on SCA

- Exercising With HCM Infographic For Clinicians Working With Student Athletes

- AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline For Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death (See Section 10.1 on athletes)

- ACC.org Expert Analysis Outlining the "How To" of Emergency Action Planning

This content was developed independently from the content developed for ACC.org. This content was not reviewed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) for medical accuracy and the content is provided on an "as is" basis. Inclusion on ACC.org does not constitute a guarantee or endorsement by the ACC and ACC makes no warranty that the content is accurate, complete or error-free. The content is not a substitute for personalized medical advice and is not intended to be used as the sole basis for making individualized medical or health-related decisions. Statements or opinions expressed in this content reflect the views of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of ACC.