For the FITs | Coronavirus and Sports Cardiology: Understanding Implications From the Individual Athlete to the Olympic Games

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is notably characterized by respiratory compromise; however, cardiovascular manifestations and complications are commonly reported.

In addition to elevations of cardiac biomarkers and electrocardiographic and echocardiographic abnormalities, the literature details a variety of associated clinical syndromes consistent with myocarditis, thrombosis, decompensated heart failure, arrhythmias and cardiogenic or mixed shock.1–4

As a result of its dramatic morbidity and mortality, the pandemic has altered international medical, cultural and economic infrastructures.

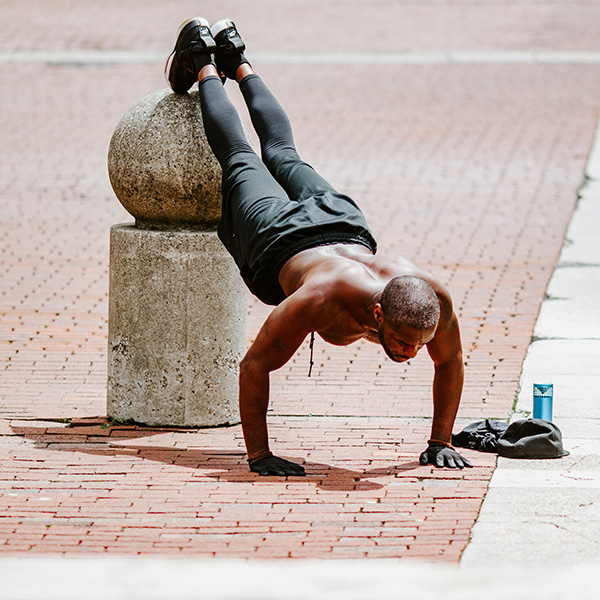

Global health measures designed to control the transmission of COVID-19 have limited public gatherings. This has necessarily disrupted the continuum of athletics. At the recreational level, many fitness centers, training gyms and public courts have closed.5

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) canceled the "March Madness" basketball tournament and is actively determining whether the college football season will proceed as originally planned.

At the professional level, the National Basketball Association, Major League Baseball and National Football League have made significant adjustments to the structure and schedule of competition. Perhaps the most symbolic representation of COVID-19's international effect on sports is the postponement of the Olympic Games, originally planned for Summer 2020 in Tokyo.

While cases are increasing in certain areas, the decline in cases in many other regions has led to strong pressure to resume sporting activities from local to professional levels.

Considerations to Return to Play by Level of Competition

High School: For competitive athletes in high school, each season is critically important for gathering attention from colleges and universities in order to compete for athletic scholarships or the opportunity to "walk-on" to a team without a scholarship.

Even for students not planning to pursue college athletics, high school sports represent an opportunity to participate in healthy behavior, social engagement and learn leadership and team-building skills.

College: For college athletes, training commonly occurs year-round despite each season officially lasting only a few months. For athletes in sports such as basketball, baseball and football, competitions are an opportunity to garner attention in hopes of being drafted into professional leagues.

Given the difference in monetary compensation typical for various draft slots, productive seasons can lead to tremendous differences in the values of professional contracts.

In that light, several prominent college football players and coaches have advocated for returning to play as soon as possible. On a larger scale, NCAA conferences must consider many factors when deciding which sports, if any, are allowed to resume. There is likely to be variation by sport, conference and school in these decisions.

Professional: There is significant pressure to resume professional sporting activities for similar reasons, albeit more intense, to high school and college athletics. Teams, cities and sponsors depend on revenue from competition and advertisements to meet financial goals.

Moreover, some athletes may feel pressure to take advantage of the years in which they are in peak physical condition. For sports with professional associations but without drafts, the prospect of Olympic team qualification or sponsorship deals depend on appropriate time to train, compete and succeed at high levels.

Considerations For the Sports Cardiologist

With pressure to return to play being applied from several angles, physicians, including sports cardiologists, are tasked with designing a return-to-play strategy that ensures the safety of individual players, coaches, support staff and fans.6,7

This endeavor is particularly challenging given the lack of full epidemiological and clinical data for symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals with proven COVID-19 and for those who have not been infected.

Several studies have suggested persistent myocardial inflammation, edema, fibrosis and impaired left and right ventricular function after recovery from COVID-19.8,9 However, the incidence of silent but smoldering myocardial inflammation after resolution of typical symptoms is unknown.7

As such, myocarditis – which is already known to be a cause of sudden cardiac death during exercise – is an even more relevant consideration in this discussion. Prior studies have shown that viral replication can be augmented by exercise, thus contributing to worsening cardiac function.10

As such, high intensity exercise in the context of undetected cardiovascular pathology may increase the risk of adverse events, including sudden cardiac arrest.11 With only limited data available, several recommendations based on international expert opinion, have been published to facilitate the return to sport.6,7,12

Cardiovascular Considerations For the Individual Athlete

Recent expert recommendations suggest an approach based on status and severity of current or prior symptoms, presence of documented infection and results of cardiac testing. The extensiveness of suggested testing varies between recommendations.5–7,11–13

COVID-19 Negative and Asymptomatic

No limitations to exercise, follow social distancing guidelines, close monitoring for development of symptoms (which would prompt a transition to an alternate pathway of evaluation).

COVID-19 Positive

Asymptomatic (in the setting of known exposure or as part of mandatory screening): Focused history and physical exam with consideration of ECG (and further imaging or provocative testing if abnormal), rest for two weeks from positive test result, monitoring for symptom onset or clinical deterioration, gradual resumption of activity after two weeks of rest under the guidance of clinicians.

Mild symptoms, not hospitalized: Focused history and physical exam, rest with no exercise during symptomatic phase and reassessment for clinical deterioration, two weeks of rest after symptom resolution followed by clinical evaluation including high sensitivity troponin (hs-Tn), 12-lead ECG, consideration of 2-dimensional echocardiogram.

Testing normal: slow resumption of activity.

Testing abnormal: consider cardiac MRI, exercise testing, ambulatory rhythm monitoring, blood gas analysis and spiroergometry, follow myocarditis return to play guidelines.14

Significant symptoms, hospitalized: Initial testing with hs-Tn, nT-proBNP, consideration of cardiac imaging per local protocols (echocardiography, exercise testing) including ambulatory rhythm monitoring.

Testing normal: Rest with no exercise while symptomatic, clinical evaluation two weeks after resolution of symptoms, slow resumption of activity under clinical guidance.

Testing abnormal: Consider cardiac MRI, spiroergometry, follow myocarditis return to play guidelines.14

Public Health Considerations

In addition to protecting individual athletes from potential cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19, sports medicine physicians and sports cardiologists must consider the public health consequences of any return to play strategy.

These considerations include:

- Protecting athletes, coaches and team personnel from physically close interactions with each other.

- Protecting team members from interactions with the public.

- Appropriate distancing between, or necessarily excluding, in-person spectators.

- International travel for competition, such as the Olympics, may spark a resurgence of cases in previously well-controlled countries.

- Countries may be differentially prepared in their abilities to address a resurgence of cases. Thus, there may be inequities between when athletes from different countries can resume competing.15,16

- Cardiovascular testing, such as exercise stress tests, may unintentionally lead to transmission and must be done in an appropriate setting with proper protective equipment.12

- Sports vary in their risk of transmission. For example, golf, singles tennis and gymnastics are more amenable to physical distancing and likely less risky than basketball, wrestling, American football and rugby.

- Differences in lifestyle between college and professional athletes within the same sport, such as private homes vs. dormitories, individual vs. shared hotel rooms, locker room size, communal vs. private commuting strategies.

A Safe Game Plan Moving Forward

Although the COVID-19 pandemic is unlike any public health crisis in the last fifty years, the decisions and strategy for resumption of sport should still be rooted in the most scientifically rigorous data available.

Some experts have called for the creation of a national registry of sudden cardiac arrest as part of a coordinated national effort to define the cardiovascular pathology associated with the disease.11

Furthermore, until there is sufficient research to define who is at highest risk for complications during exercise, it is prudent to ensure that all competitions have adequate access to medical personnel and automatic external defibrillators.

Perhaps the most important lesson about resuming sporting activities is actually recognizing the signals that would necessitate another stop in play.

These may include:

- A rise in cases within specific teams or sports

- Inappropriate access to antigen and antibody testing

- A shortage of personal protective equipment; or

- In the worst-case scenario, sudden cardiac arrest among athletes

As Kenny Roger's song "The Gambler" notes, "You've got to know when to hold 'em/Know when to fold 'em/Know when to walk away/And know when to run."

Visit the Sports and Exercise Cardiology Member Section for more on COVID-19 and return-to-play, including an on-demand webinar and Quick Tips Video. And don't miss the recap of the Care of the Athletic Heart Virtual 2020.

References

- Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, et al. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2020;141:168-55.

- Fried JA, Ramasubbu K, Bhatt R, et al. The variety of cardiovascular presentations of COVID-19. Circulation 2020;141:19306.

- Gupta AK, Jneid H, Addison D, et al. Current perspectives on coronavirus disease 2019 and cardiovascular disease: A white paper by the JAHA Editors. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9(12):e017013.

- Driggin E, Madhavan M V, Bikdeli B, et al. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:2352-71.

- Löllgen H, Bachl N, Papadopoulou T, et al. Recommendations for return to sport during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2020;6(1):e000858.

- Phelan D, Kim JH, Chung EH. A game plan for the resumption of sport and exercise after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Infection. JAMA Cardiol 2020;May13:[Epub ahead of print].

- Baggish A, Drezner JA, Kim J, Martinez M, Prutkin JM. Resurgence of sport in the wake of COVID-19: cardiac considerations in competitive athletes. Br J Sports Med 2020;June 19:[Epub ahead of print].

- Huang L, Zhao P, Tang D, et al. Cardiac involvement in patients recovered from COVID-2019 identified using magnetic resonance imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020;Aug 19;[Epub ahead of print].

- Puntmann VO, Carerj ML, Wieters I, et al. Outcomes of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients recently recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020;July 27:[Epub ahead of print].

- Gatmaitan BG, Chason JL, Lerner AM. Augmentation of the virulence of murine coxsackie-virus B-3 myocardiopathy by exercise. J Exp Med 1970;131:1121-36.

- Baggish AL, Levine BD. Icarus and sports after COVID 19: Too close to the sun? Circulation 2020;142:615-7.

- Dores H, Cardim N. Return to play after COVID-19: a sport cardiologist's view. Br J Sports Med 2020;May 7:[Epub ahead of print].

- Bhatia RT, Marwaha S, Malhotra A, et al. Exercise in the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) era: A question and answer session with the experts endorsed by the section of Sports Cardiology and Exercise of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020;27:1242-51.

- Maron BJ, Udelson JE, Bonow RO, et al. Eligibility and disqualification recommendations for competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities: Task Force 3: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and other cardiomyopathies, and myocarditis: Circulation 2015;132:e273-80.

- Anderson RM, Heesterbeek H, Klinkenberg D, Hollingsworth TD. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet 2020;395:931-4.

- Mann RH, Clift BC, Boykoff J, Bekker S. Athletes as community; athletes in community: COVID-19, sporting mega-events and athlete health protection. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:1071-2.

Clinical Topics: COVID-19 Hub, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Prevention, Sports and Exercise Cardiology, Exercise, Sports and Exercise and ECG and Stress Testing

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, COVID-19, Sports, Pandemics, Football, Exercise Test, Fellowships and Scholarships, Seasons, Basketball, Gymnastics, Baseball, Mandatory Testing, Coronavirus, Coronavirus Infections, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

< Back to Listings