Peripheral Matters | Supervised Exercise Therapy For Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease

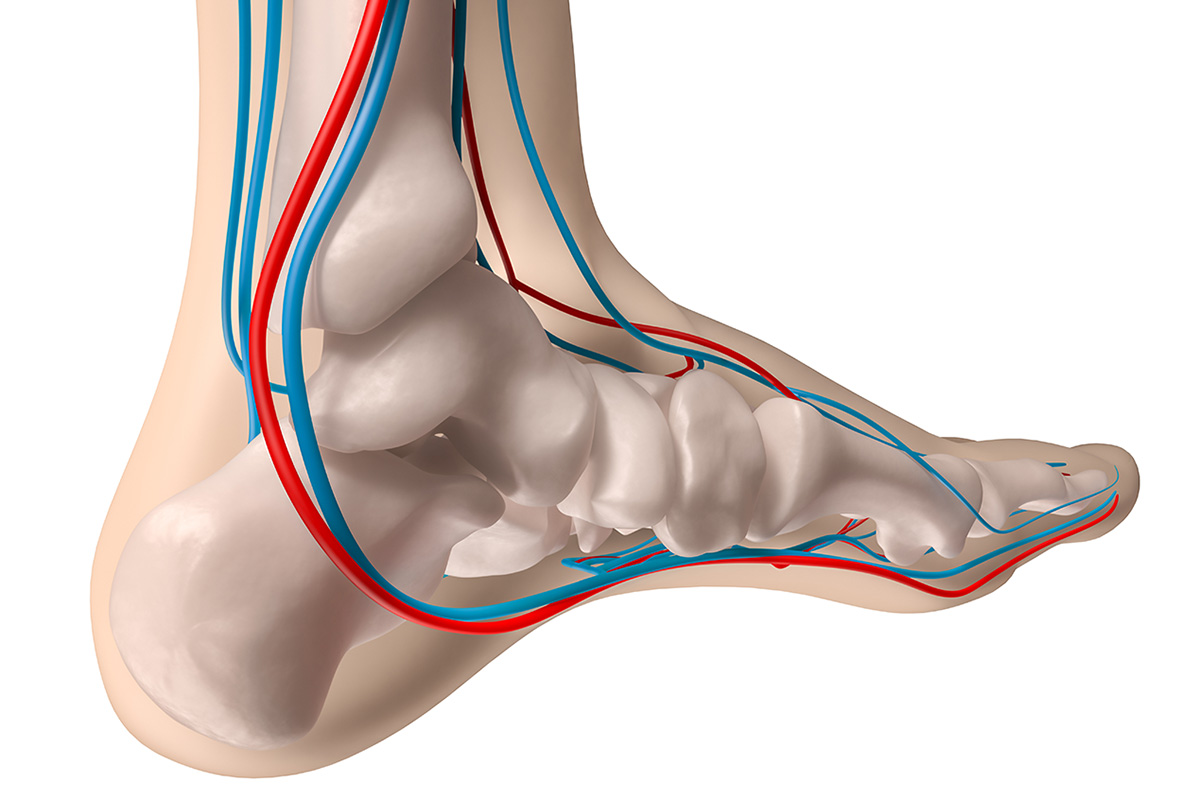

Lower extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD) is the third leading cause of atherosclerotic vascular morbidity after coronary heart disease and stroke.1 It is estimated that over 200 million people worldwide2 and 8.5 million Americans over the age of 403 have PAD.

Intermittent claudication from PAD is known to affect approximately 4.5% of the general population at or over the age of 404 and it is independently associated with an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality5, 6 and marked reductions in quality of life.7, 8

Unfortunately, few effective treatments exist for intermittent claudication.9 Cilostazol is the only effective medical therapy to improve symptoms but is not widely utilized.10 Pentoxifylline is the only other medication that has U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of PAD-related walking impairment,11 but is no longer guideline-recommended due to lack of data supporting its efficacy.10

Supervised exercise therapy (SET) is an effective intervention to reduce lower extremity symptoms in patients with intermittent claudication from PAD. Due to data from several trials, including ones with long-term follow-up,12-14 consensus guidelines recommend SET to improve functional status and quality of life, and to reduce leg symptoms.10

The guidelines also recommend SET prior to consideration of revascularization, as well as a key part of combination therapy in patients who undergo revascularization for refractory sytmptoms.10

The Endovascular Revascularization and Supervised Exercise (ERASE) study found that after one year of follow-up, combination therapy with endovascular revascularization followed by SET resulted in significantly greater improvement in walking distances and quality of life scores compared with SET only in patients with PAD and stable claudication for at least three months.15

Until 2017, the lack of reimbursement for this therapy greatly limited access and utilization.16 However, in 2017, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) "determined that the evidence [was] sufficient to cover SET for beneficiaries with intermittent claudication for the treatment of symptomatic PAD" (CPT code: 93668). Up to 36 sessions are covered over a 12-week period if all the components listed in Table 1 are met.

Table 1: CMS Requirements For Supervised Exercise Therapy Program

| Session Requirements | Sessions lasting 30-60 minutes comprising therapeutic exercise-training program for peripheral artery disease in patients with claudication |

| Setting Requirements | Conducted in a hospital outpatient setting or a physician's office |

| Delivery and Supervision Requirements | Delivered by qualified auxiliary personnel necessary to ensure benefits exceed harms, and who are trained in exercise therapy for peripheral artery disease |

| Under the direct supervision of a physician, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner/clinical nurse specialist who must be trained in both basic and advanced life support techniques |

In addition, beneficiaries must have a face-to-face visit with the physician responsible for PAD treatment to obtain the referral to SET, and the beneficiary must receive information regarding cardiovascular disease and PAD risk factor reduction at this visit.

Graded treadmill-based exercise prescriptions are the foundation of SET. After a five-minute warm-up period, participants are asked to walk on the treadmill using provider- and patient-centered protocols until they have mild to moderate pain (3-4 of 5 on the claudication scale17, 18).

They are then asked to stop, sit down and rest until the pain has completed resolved. Then they resume walking. The goal is to reach an exercise session of 50 minutes in duration (including rest periods), which allows for five-minute warm-up and cool-down periods to bring the total session duration to 60 minutes.

Progression of the intensity of the exercise prescription typically occurs between sessions, not during a session. Commonly utilized graded protocols in SET Programs are listed in Table 2.19-22

Table 2: Standardized Graded Treadmill Exercise Protocols For Supervised Exercise Therapy

| Gardner-Skinner Protocol19 | Hiatt Protocol20 | Bronas/Treat-Jacobson Protocol21 |

|

|

|

*Patients unable to start walking at 2 miles per hour can start at 0.5 miles per hour and increase speed by 0.5 miles per hour every 2 minutes until a speed of 2 miles per hour is reached.

In addition to graded exercise test-based metrics, functional evaluation can be done at intake and exit sessions with a six-minute walk test.23, 24 Symptom and quality of life assessments can be done via disease-specific questionnaires, such as the Walking Impairment Questionnaire (WIQ)25 and the Peripheral Artery Questionnaire (PAQ),26 and other validated metrics.

In addition to improving access to guideline-recommended care for patients with PAD and providing patient-centered care, the establishment and growth of a SET Program provide opportunities to build on intra- and inter-institutional collaboration between cardiovascular medicine, interventional cardiology and vascular surgery programs.

Benefits include direct revenue generation through a service offering, referrals to a center's vascular lab, vascular imaging center, cardiovascular medicine and vascular surgery clinics, and interventional and surgical programs, and opportunities for research.

Importantly, many centers already have the infrastructure needed to build a SET Program via their existing cardiac rehabilitation and/or physical therapy programs.22, 27

After rolling out the Program on a small scale, it can grow quickly with referrals and charges that will allow for resource allocation requests. With increases in enrollment, research programs and quality improvement initiatives can be built within SET Programs.

An important contemporary consideration due to the COVID-19 pandemic is that home-based exercise regimens for intermittent claudication from PAD, while less effective than SET, may be reasonable options.

Many cardiac rehabilitation and physical therapy centers remain closed or have drastically limited the number of patients they serve. Studies have shown that home-based programs can improve walking endurance and physical activity in patients with PAD.28

In summary, SET is a data-supported and guideline-recommend treatment for patients with intermittent claudication from PAD. It is our responsibility as a cardiovascular community to improve access to this important treatment, particularly now that it is a reimbursed service by CMS for Medicare beneficiaries, and by many private insurers.

Join the ACC in Recognizing PAD Awareness Month

All year long, visit ACC.org to access the tools, resources and education you need to treat your patients with PAD. Don't miss the Peripheral Vascular Disease Member Section and the Vascular Medicine Clinical Topic Collection.

Click here for CardioSmart's PAD Condition Center for tools to help patients better understand their condition including a downloadable infographic, resources to find support, questions to ask their physicians, and more.

Make sure to join the conversation on Twitter using #PADawareness and tagging @ACCinTouch.

References

- Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet 2013;382:1329-40.

- Criqui MH, Aboyans V. Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease. Circ Res 116:1509-26.

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016;133:e38-360.

- Fakhry F, Fokkenrood HJ, Spronk S, et al. Endovascular revascularisation versus conservative management for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 03 2018;3:CD010512.

- Golomb BA, Dang TT, Criqui MH. Peripheral arterial disease: morbidity and mortality implications. Circulation 2006;114:688-99.

- Smith GD, Shipley MJ, Rose G. Intermittent claudication, heart disease risk factors, and mortality.The Whitehall Study. Circulation 1990;82:1925-31.

- Khaira HS, Hanger R, Shearman CP. Quality of life in patients with intermittent claudication. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1996;11:65-9.

- Spronk S, White JV, Bosch JL, Hunink MG. Impact of claudication and its treatment on quality of life. Semin Vasc Surg 2007;20:3-9.

- Berger JS, Hiatt WR. Medical therapy in peripheral artery disease. Circulation 2012;126:491-500.

- Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1465-1508.

- McDermott MM. Reducing disability in peripheral artery disease: The role of revascularization and supervised exercise therapy. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2019;12:1137-9.

- Fakhry F, Rouwet EV, den Hoed PT, et al. Long-term clinical effectiveness of supervised exercise therapy versus endovascular revascularization for intermittent claudication from a randomized clinical trial. Br J Surg 2013;100:1164-71.

- Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, Regensteiner JG, et al. Supervised exercise versus primary stenting for claudication resulting from aortoiliac peripheral artery disease: six-month outcomes from the claudication: exercise versus endoluminal revascularization (CLEVER) study. Circulation 2012;125:130-9.

- Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, Regensteiner JG, et al. Supervised exercise, stent revascularization, or medical therapy for claudication due to aortoiliac peripheral artery disease: the CLEVER study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:999-1009.

- Fakhry F, Spronk S, van der Laan L, et al. Endovascular revascularization and supervised exercise for peripheral artery disease and intermittent claudication: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;314:1936-44.

- Harwood AE, Smith GE, Cayton T, et al. A systematic review of the uptake and adherence rates to supervised exercise programs in patients with intermittent claudication. Ann Vasc Surg 2016;34:280-9.

- Weinberg MD, Lau JF, Rosenfield K, Olin JW. Peripheral artery disease. Part 2: medical and endovascular treatment. Nat Rev Cardiol 2011;8:429-41.

- Olin JW, White CJ, Armstrong EJ, et al. Peripheral artery disease: Evolving role of exercise, medical therapy, and endovascular options. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:1338-57.

- Gardner A, Skinner J, Cantwell B, Smith L. Progressive vs single-stage treadmill tests for evaluation of claudication. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1991:402-8.

- Hiatt WR, Regensteiner JG, Hargarten ME, et al. Benefit of exercise conditioning for patients with peripheral arterial disease. Circulation 1990;81:602-9.

- Treat-Jacobson D, Bronas UG, Leon AS. Efficacy of arm-ergometry versus treadmill exercise training to improve walking distance in patients with claudication. Vasc Med 2009;14:203-13.

- Treat-Jacobson D, McDermott MM, Beckman JA, et al. Implementation of supervised exercise therapy for patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease: A science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;140:e700-e710.

- Guyatt GH, Sullivan MJ, Thompson PJ, et al. The 6-minute walk: a new measure of exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Can Med Assoc J 1985;132:919-23.

- McDermott MM, Guralnik JM, Criqui MH, et al. Six-minute walk is a better outcome measure than treadmill walking tests in therapeutic trials of patients with peripheral artery disease. Circulation 2014;130:61-8.

- Regensteiner JG, Steiner JF, Hiatt WR. Exercise training improves functional status in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg 1996;23:104-15.

- Spertus J, Jones P, Poler S, Rocha-Singh K. The peripheral artery questionnaire: a new disease-specific health status measure for patients with peripheral arterial disease. Am Heart J 2004;147:301-8.

- Salisbury DL, Whipple MO, Burt M, et al. Experience implementing supervised exercise therapy for peripheral artery disease. J Clin Exerc Physiolr 2019;8:1-12.

- McDermott MM, Liu K, Guralnik JM, et al. Home-based walking exercise intervention in peripheral artery disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;310:57-65.

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, COVID-19 Hub, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Prevention, Vascular Medicine, Atherosclerotic Disease (CAD/PAD), Exercise

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Intermittent Claudication, Peripheral Arterial Disease, Exercise Test, Walking, Cardiac Rehabilitation, Pentoxifylline, COVID-19, Quality of Life, Risk Factors, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, U.S., Current Procedural Terminology, Medicare, Nurse Clinicians