Feature | Leading With Grace: The Story of Dr. Josephine Isabel-Jones

Reading her words, we can only wonder how retired pediatric cardiologist Josephine Isabel-Jones, MD, FACC, rose to the heights she attained. She was Black. She was a woman. She grew up in a country sharply divided along racial lines and in the throes of the Civil Rights Movement. The field of medicine she aspired to enter was wholly dominated by White men.

How is it possible she became the first African-American woman to become a board-certified pediatric cardiologist in the U.S. and became the inspiration for other Black women to follow in her footsteps? A life filled with many "firsts" was filled with activism and advocacy, and endless ambition and success, all fueled by the extraordinary family who raised her.

The Spark

Isabel-Jones' parents, the Isabels, were well known activists in the Memphis community. Their desire to build a better, just community was evident long before the names Martin Luther King Jr., and Rosa Parks were known. Mrs. Isabel earned her GED after her own children started school and received her bachelor's degree in education over a decade. Eventually she became one of the first Black teachers recruited to integrate an all-White school when integration began to roll out in Memphis, in part due to the Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 that ruled segregated public schools were unconstitutional.

Mr. Isabel, a natural leader and self-made electrician armed with a high school diploma and some college, became the first African-American licensed electrician in Tennessee and became the first department supervisor at the local electrical company, Buckeye Cellulose (then a subsidiary of Procter and Gamble).

The integration of schools revealed disparities and inequities between Blacks and Whites in education, employment and other areas. A young Isabel-Jones was pulled into the community activism of her parents, at one time using her skills as a typist to prepare letters to the mayor and city council of Memphis to petition for remedies to segregation and discrimination on many fronts. This baptism into community service forecasted her activism in the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement.

Dreaming the Impossible Dream

When she was eight years old, Isabel-Jones decided to be a pediatrician. In the 1940s, it was unheard of for Black girls from the segregated South to become doctors – and she'd never even met a woman who was a physician. Yet she believed this was her calling.

Her parents were encouraging, despite the barriers and social precedents. When hearing comments that their daughter would make an "excellent nurse," they were quick to make it clear her goal was to be a physician. "I had support early to dare to do things differently… as my parents had demonstrated," says Isabel-Jones. They'd instilled in her the fortitude required to navigate a career in medicine, where there was a scarcity of individuals who looked like her.

A purpose-driven student, Isabel-Jones skipped a grade in elementary school, was her high school valedictorian, and earned a four-year college scholarship from the Black Greek-lettered organization, Alpha Kappa Alpha (AKA) sorority, one of only two organizations that awarded scholarships to Black female high school graduates.

In her high school years, her activism was through the Girl Scouts, because they "did things I enjoyed doing...to be in the community doing things that you felt was of some help to somebody." She was also involved in marching band and ballet, and she continues to be an avid lover of ballet and participates in a creative dance ministry at her church.

At Lemoyne College in Memphis, Isabel-Jones pursued premed studies and completed her major in biology in three years. Along with being a cheerleader and pledging the AKA sorority, she was heavily involved in student government.

As a second-year college student, she participated in voter registration just as the rumblings of the Civil Rights Movement were peaking in states such Alabama, Georgia and North Carolina. In 1960, a former graduate of LeMoyne who had been involved in the sit-ins that took place in North Carolina returned to Memphis. He encouraged the students to organize and stage their own demonstrations to protest the segregation policies.

As vice president of the student body in her senior year, Isabel-Jones answered this call to action – leading a series of sit-ins that led to the desegregation of the Memphis Public Library and other public facilities in Tennessee.

A book she needed to complete her required capstone project was available locally only at the Whites-only library. Ordering it through the Black-only local library would require waiting at least two weeks for delivery. It was unfair and unjust and she was infuriated. She persuaded her fellow student leaders to hold their first sit-in at the two Whites-only libraries in Memphis. On a fateful day in April 1960, the Lemoyne students split up and took public transportation to each of the Whites-only libraries, arriving at the same time – surprising city officials who had prepared for such demonstrations at the lunch counters, as was happening across the South, not at the library!

A Formidable Career

Though engulfed in the Movement and reveling in the strides made in Memphis, Isabel-Jones adopted a new priority that demanded her attention when she entered Meharry Medical College, a historically Black institution in Nashville. Just one of four women in a class of 70 in 1960, she confronted a new "-ism": sexism. Many of the Black male students felt the women had taken spots away from other male candidates. A bias similar with what many women have described in majority medical schools.

All four of the women graduated and Isabel-Jones was inducted into the Alpha Omega Alpha Medical Honor Society. Her medical school training included an externship in family medicine in Syracuse, NY, and an internship at DC General Hospital in Washington, DC.

Her first interest in cardiology was sparked by time spent early in her training with an adult cardiologist. During her internship in DC, she attended a city-wide cardiology conference organized by Joseph K. Perloff, MD, FACC. He later became a founder of the subspecialty of Adult Congenital Heart Disease and became Isabel-Jones' colleague at UCLA in the late 1970s.

Thinking strategically to establish herself as a pediatrician in Memphis, Isabel-Jones moved there to complete her pediatric residency and became University of Tennessee's (UT) first African-American resident. She recalls it as a lonely, isolating experience with little support and few connections, even though living in her hometown. Lorin E. Ainger, MD, FACC, a pediatric cardiologist, convinced her to stay at UT for an additional year and continue as a pediatric cardiology fellow as she seemed to have a knack for it. As Isabel-Jones recounts, "sometimes it just takes someone saying you are good at something to change your life's course."

Ainger treated her just as he would any other Fellow. When a cardiology conference was hosted at the local country club, he of course took her with him. When she entered the country club, she was the first-ever Black guest, at a place where her father had worked part time as a head waiter.

Isabel-Jones completed her pediatric cardiology fellowship at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). In 1969, she went to Duke University as part of her oral boards, where she was tested by well-known pediatric cardiologist Madison S. Spach, MD, FACC. She felt defeated after the examination, only to learn later she had indeed passed – making her the first African-American woman board-certified in pediatric cardiology in the U.S.

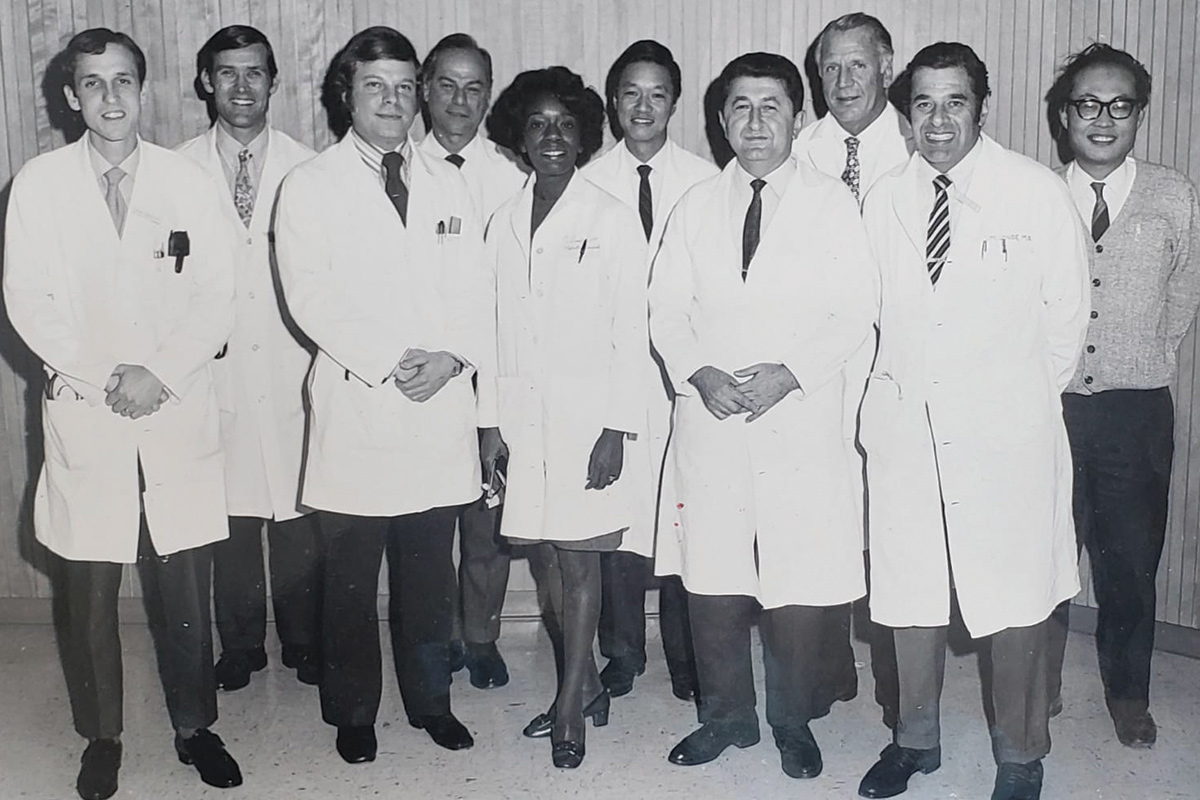

At the invitation of Arthur J. Moss, MD, FACC, one of the founders of pediatric cardiology, Isabel-Jones, recently married to Earl Jones, joined the faculty at UCLA. Among her roles there were director of the catheterization lab and director of the echocardiography lab and she led a storied career; she is now professor emeritus of pediatrics. Her honors include the Carol E. Goldberg Emeriti Service Award for exemplary service to the university and her department.

The care of children with heart disease took her beyond the walls of UCLA into the greater Los Angeles community. Isabel-Jones provided expertise to Black and Hispanic children at Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Hospital in South Central Los Angeles. And she worked alongside Black pediatric cardiologist Ernest H. Smith, MD, well known for his advocacy and activism in the Watts community.

Her altruism crossed borders as she volunteered with Hearts with Hope (Corazones con Esperanza) for more than a decade, assisting an organization that provides much needed cardiac care for underserved children in Peru. Mirroring her activities in Los Angeles, she left the confines of the children's hospital in the capital of Lima and journeyed to Arequipa to provide outreach to villages and mountain communities. In addition to catheterizations and surgeries, Hearts with Hope interventions extended beyond cardiac care, with Isabel-Jones facilitating care of any malady encountered.

She learned firsthand what it's like to receive medical care in a developing country, when she and her two daughters were critically injured on the first day of a medical mission to Zimbabwe in 1992, reinforcing her continued commitment to international medical philanthropy.

Isabel-Jones' drive, commitment and sense of community has inspired other women of color in pediatric residencies at UCLA to become pediatric cardiologists. The women who became the second and third board-certified pediatric cardiologists, Brenda Armstrong, MD, and Sylvia Swilley, MD, FACC, respectively, hail her as their mentor.

Another first for Isabel-Jones was being the assistant dean of Student Affairs, through which she helped to create a more diverse medical school at UCLA. Through this work as well as on the UCLA's medical school admission committee, at the request of her colleague Leonard Linde, MD, she brought a wider lens and a more holistic view of how candidates were selected. "I did everything to justify, defend and advocate for these students," she says. While progress has been made, she would be the first to admit the struggle continues.

The Fire Still Burns

Isabel-Jones' passion for driving change – gracefully – continues to this day. Undaunted and unbothered, this petite 80-year-young Black woman shared her perspective and wisdom with a group of men wearing masks and carrying assault rifles while participating in a demonstration led by the Proud Boys. It was the summer of 2020 and Black Lives Matters demonstrations were growing in numbers in a racial reckoning after the unspeakable death of Mr. George Floyd.

She was visiting her daughter in a small town in Utah when she saw the group and asked them what was happening. One person said they were there to preserve the peace and protect their families and police. The group was concerned about the Black Lives Matter movement spreading into their neighborhoods.

In a skillful, nonjudgmental manner, she shared that carrying arms went against the peace they were trying to create. And clarified that while there may be instigators and agitators among people claiming to be part of the movement, people true to the movement were peaceful demonstrators. She shared her belief that groups can come together and create solutions for social ills in our communities. But, she noted, "you can't walk around with weapons and expect to live to be 80."

What keeps her grounded? Her deep faith. Feeling blessed, she says, "I don't do stress." Her calmness in testy situations led colleagues to write on her office whiteboard: "Grace Under Pressure." This internal peacefulness would almost seem at odds with the feistiness displayed throughout her life. But this amalgam settled in a woman who followed her calling to pediatric cardiology. In the process, she has lived a life and built a legacy with an undercurrent of advocacy and activism. Her trailblazing career has made the impossible possible for many. Not bad for a little Black girl living in the segregated South.

This article was authored by Annette K. Ansong, MD, FACC, pediatric cardiologist and medical director of Outpatient Cardiology at Children's National Medical Center in Washington, DC, and contributors Sylvia S. Swilley, MD, FACC, and Barbara Sternlight McCarthy, BA, RDMS. They express gracious acknowledgements to Roberta G. Williams, MD, MACC; Arwa Saidi, MB BCh, FACC, and ACC's Adult Congenital Pediatric Cardiology Leadership Council for their support and assistance with this article.

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Noninvasive Imaging, Congenital Heart Disease, CHD and Pediatrics and Imaging, CHD and Pediatrics and Prevention, CHD and Pediatrics and Quality Improvement, Echocardiography/Ultrasound

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Aesculus, African Americans, Altruism, Attention, Awards and Prizes, Biology, Books, Burns, Capparis, Cardiology, Catheterization, Cellulose, Civil Rights, Dancing, Developing Countries, Echocardiography, Educational Status, Employment, European Continental Ancestry Group, Faculty, Family Practice, Fathers, Fellowships and Scholarships, Firearms, Goals, Government, Healthcare Disparities, Hearing, Heart Defects, Congenital, Heart Diseases, Hispanic Americans, Hospitals, General, Internship and Residency, Leadership, Lunch, Masks, Medical Missions, Medicine, Mentors, Mothers, Nuclear Family, Outcome Assessment, Health Care, Outpatients, Pediatrics, Physician Executives, Police, Policy, Public Facilities, Reading, Schools, Schools, Medical, Sexism, Social Welfare, Students, Universities

< Back to Listings