Business of Medicine | Cardiology Practice Models: Is One Better Than Another?

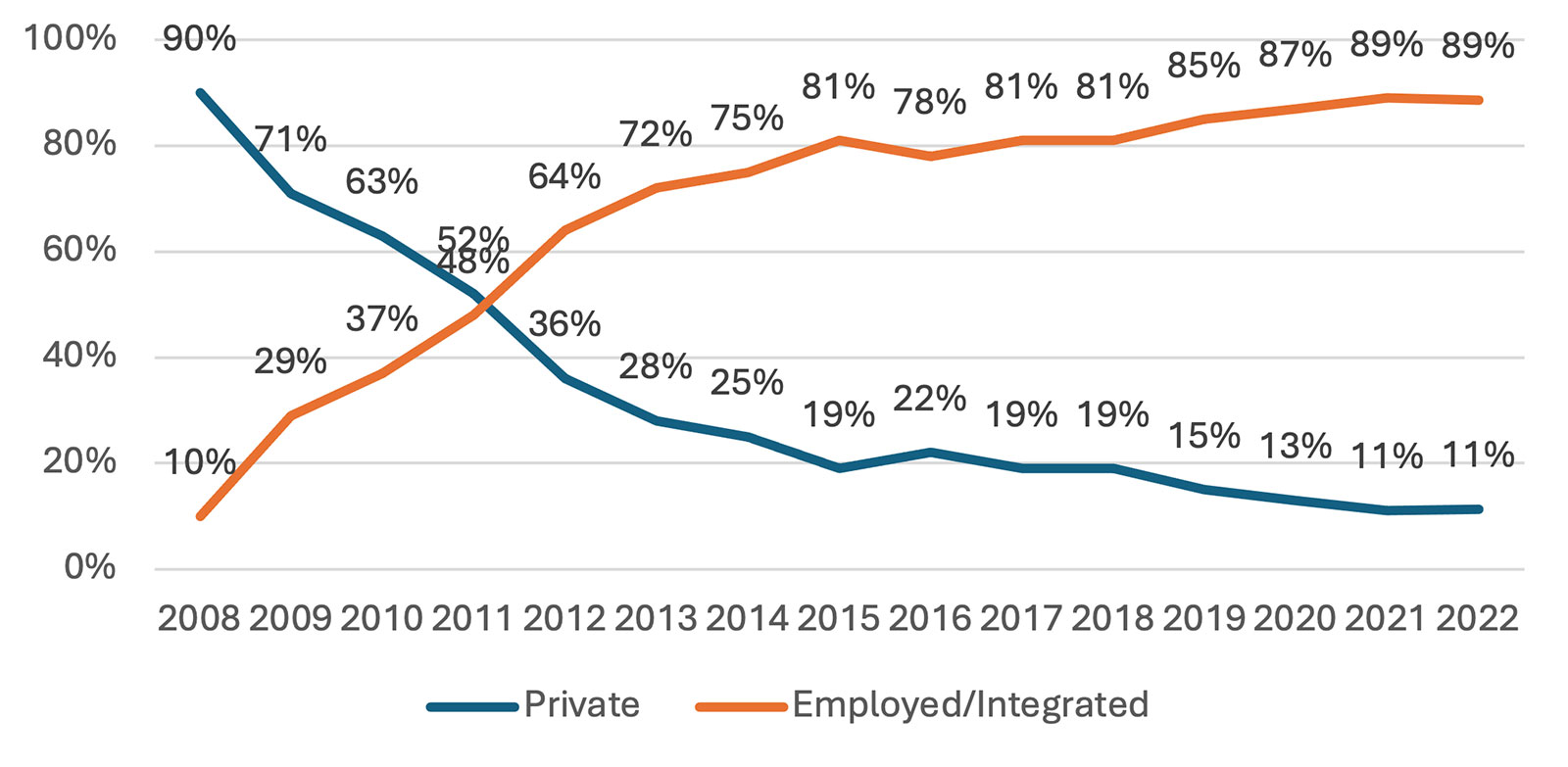

Until about 15 years ago, most cardiologists were found in private practices, where the physicians – usually in groups – owned the practice and had privileges for hospital-based services at one or more hospitals in their area. During this time, the smaller subset of cardiologists who were "employed/integrated" with a hospital/health system tended to be academic physicians.

A series of Medicare reimbursement cuts to certain imaging procedures starting in 2008 led to a paradigm shift of cardiologists to hospital/health system integration, with more than half of cardiologists shifting from private to integrated practices within five years, reaching nearly 90% by 2022 (Figure 1).

Driven mainly by federal policy changes with respect to certain cardiac procedures being moved off the "inpatient only" list and becoming eligible for reimbursement in the ambulatory setting, there are signs that another migration of cardiologists may be upon us.

While too early to tell, there have been sporadic episodes of cardiologists leaving hospital employment and reconstituting private groups in recent years. The data show the number has not yet lowered the percentages, but there has been much speculation these occurrences are the start of something much bigger. Additionally, private equity (PE) has recently emerged as a hybrid alternative to private practice.

So which integration model is optimal? Here we explore the pros and cons of the three main models: employment, professional services agreements (PSAs) and PE.

Figure 1. Cardiology Group Ownership Trend (Survey Participants)

Private Practice

In a private cardiology practice, the physicians are the legal owners of the entity. The owners manage all aspects of the practice, from staffing to contracting to hospital coverage decisions. These physicians will almost always have privileges at one or more hospitals for performing procedures and providing inpatient cardiac care. They are, however, independent from those hospitals unless in some form of formal contract arrangement.

For instance, according to 2023 MedAxiom data, the vast majority of private groups receive some form of financial payment from one or more hospitals. This can be in the form of formal co-management agreements (where physicians can earn money through the achievement of specific value metrics), call coverage arrangements, outreach clinic coverage and the like.

The advantages of the private group model include physicians being independent and making their own decisions relative to staffing support, information technology (IT) choices, payer contracting, fringe benefits packages and other key practice areas important to physicians. These groups also tend to be much nimbler and more innovative in their respective markets with decisions being made and implemented within a very short time.

With authority comes accountability; a major disadvantage of the private group model is that physicians are completely at financial risk. Changes to reimbursement or loss of a significant payer contract can significantly hurt financial performance, with no safety net for these events. Leading and managing a practice takes time and effort, a burden on top of already busy and full-time clinical practices.

In addition, according to MedAxiom survey data, cardiologists in private groups work harder and are paid less than their hospital-integrated peers, which is captured starkly in total compensation per work relative value units (wRVUs) (Figure 2). This disadvantage in pay can make recruitment difficult when competing with a hospital for talent.

Employment

According to MedAxiom data, nearly 90% of cardiologists integrated with a hospital or health system are W-2 employees. Only a small handful are integrated through a PSA. These physicians typically have a formal employment agreement – although lately there is a movement away from these contracts – that lays out specific terms for the relationship, including but not limited to duration, terms of separation/dissolution and compensation. Just over half of hospital-employed cardiologists are paid on a straight productivity model, with the predominant production currency being wRVUs (Figure 3).

Regardless of the wide variety of different terms and incentives in employment relationships, employment is often advantageous. For example, a physician can work in an area that needs special access, such as underserved populations or Medicaid patients. Those areas would be financially disadvantageous for private practice physicians and a typical employment relationship would be agnostic. Physicians are often buffered from some of the effects of overhead, payer mix and collection activities.

Additionally, physicians in employment relationships have resources for IT issues, marketing and business office support, as well as benefits and staff recruiting – all of which may not be available in private practice or may involve the physician taking on an "extra job" to accomplish many of these tasks.

With significant employer support, physicians can have referrals directed towards their employer or network and have the compensation set in advance. This is an advantage that allows the physicians to operate a successful practice by removing many of the responsibilities that physicians would otherwise oversee.

Even in a reformed/value-based care environment, it is unlikely that employment will cease to exist. It is important to have other types of reliable relationships for those who do not want to be employed, such as risk-bearing entities/network opportunities and joint ventures. However, it appears that employment will remain a strong alignment tool for the foreseeable future.

The main nonlegal advantage of employment is financial stability, in terms of total compensation relative to work and in protection against negative changes in reimbursement and practice expense increases. In addition, physicians can simply focus on their clinical activities without the burden and distraction of running a business.

There is a business adage that whoever controls the money, controls the business. A major disadvantage of hospital employment is a loss of autonomy for the physicians who are not unilaterally in control of staffing ratios, technology choices and the like. These decisions impact financial performance and because the hospital is completely at risk, they tend to play an oversized role in these decisions.

Due to accounting and regulatory issues, employed cardiology practices tend to "lose money." Thus, there is constant pressure to reduce costs in the physician enterprise, which can often lessen provider support. This "operating at a loss" can be a demoralizing position for physicians.

Professional Services Agreements

PSAs are typically characterized by physician-owned organizations contracting all or part of the practice to a hospital or health system. In some cases, the hospital provides all the practice support elements (staff, space, billing and collections, etc.), and only the cardiology providers are leased through the PSA. In other circumstances, the entire practice is leased.

In either model, the practice is paid as a 1099 or independent contractor. Through their internal governance, physicians then address practice overhead, hiring and firing of staff, distribution of income, scheduling, and related issues that are typically covered by the employer in an employment relationship.

Independent contractor relationships must still qualify for a Stark exception or anti-kickback safe harbor. The professional services exception under Stark has the following requirements:

- The arrangement must be in writing.

- Compensation must be set in advance.

- The transaction must be within fair market value, commercially reasonable, and not in a manner that considers the volume or value of referrals or business otherwise generated between the parties.

This is navigable for most groups, but it does require maintenance. It limits the type of payments that can be made so as not to incentivize referral of business beyond those services performed by group members.

PSAs are a good alignment vehicle in times of modern and evolving payment models. Some hospitals are leery that PSAs may result in the practice continuing to seek other opportunities which creates concern that there might be a second transaction offered.

For example, the group may disintegrate, merge or be sold to PE (see below), and this might be contrary to the partnership/affiliation relationship sought by the health system. Despite these concerns, there has been an increased interest in PSAs as health systems struggle with financial operating margins. The PSA model can provide a hospital with a solid cardiology coverage, while shielding it from the full practice financial risk that employment brings.

The advantage of a PSA is that they often feel more like private practice, which gives the physician a greater zone of control, particularly around income distribution and establishing fringe benefit packages. If it is a full practice PSA, including the support services, the model provides great flexibility if the physicians should later choose to leave the agreement. This would obviously be impacted by noncompetes and other terms within the PSA.

At the end of the PSA's contractual duration, a new agreement must be negotiated. Hospitals still tend to favor employment over the PSA for legal reasons. If a practice cedes its support services to the hospital as part of the PSA, this model provides few advantages over employment in terms of flexibility and ease of exit.

Private Equity

CV Transforum Fall'24

Plan to be in Denver on Oct. 17-19 for MedAxiom's CV Transforum, featuring interactive, industry-leading education, and meet the authors. Click here to learn more and register.

Fueled by a recent and significant movement of "hospital-only" services to be eligible for reimbursement in the ambulatory setting (such as ambulatory surgery centers [ASCs]), PE has become keenly interested in acquiring cardiology practices. In this model, the PE firm buys all or part of the cardiology practice and provides management services back to the group.

The intent is to aggregate physicians and then sell the entire PE entity to a larger investor, thereby creating a second value stream. The first targets are the remaining private cardiology practices but eventually PE will turn to hospital-employed groups too.

The main advantages of PE integration are that the physicians mostly control the support functions of the practice, and the physician owners receive an upfront cash payment. However, this payment is typically tied to an income reduction that creates the value in the group for the PE entity. The hope is to "repair" this lost income through practice efficiencies and scale and added services, such as development of a cardiac ASC. Another advantage is that the group is still independent in the market and not beholden to one hospital or health system.

A major disadvantage of the PE model is the intentional reduction in income for physicians. If repair of this deficit is slow to occur – or never occurs – it is difficult to retain cardiologists long term. Also, the physicians have no say or control in the inevitable and planned second sale. Thus, sometime in their future they will be partnered with an entity they may know nothing about with a very different culture than with the original buyer.

Conclusion

While most cardiologists are currently in a hospital employment model, it is not the only integration option available. PSAs are experiencing a rise in popularity as physicians look to take back more control over their practice support and hospitals look to shed financial risk. Additionally, this model is ideally suited to take advantage of evolving payment models and risk-based arrangements.

Private groups have the advantage of independence and nimbleness, and sole responsibility for financial performance, but only a small fraction of groups remain in this model. In just a few years the newcomer, PE, has acquired a significant number of private cardiology practices, particularly in less legislatively restrictive states like Florida and Texas. The degree to which this model ultimately impacts the cardiology landscape and its durability remain to be seen.

Recently, the Federal Trade Commission issued a ruling that is limiting the application of noncompetes, and many state initiatives have also been established to curb these restrictive covenants. These changes could have a significant impact on hospital integration models, making it easier for physicians to move to another entity.

This article was authored by Jim Daniel Jr., JD/MBA, partner, Hancock, Daniel & Johnson, P.C., and Joel R. Sauer, MBA, executive vice president, Consulting, MedAxiom.

Keywords: Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications, Private Practice, Employment, Ownership, Medicare