Peripheral Matters | Lymphedema: Growing Treatment Options for an Underappreciated Disease

Lymphedema is a poorly recognized and underappreciated disease state with significant morbidity. It is a chronic, incurable disease that can be progressive in nature if left untreated. Despite its relatively high prevalence, lymphedema is poorly recognized and undermanaged by physicians. Until recently, there have been few treatment options beyond compression and manual lymph drainage (MLD) guided by certified lymphedema therapists.1 Here we discuss the background of lymphedema and the growing management options for prevention and treatment of chronic lymphedema.

Understanding Lymphedema

The lymphatic system is essential for fluid homeostasis, in addition to vital roles in the immune system and fat absorption. When lymphatic flow is suboptimal, there is accumulation of excess fluid within the interstitial space, which results in a localized inflammatory milieu leading to fibrosis and adipose deposition.2,3

Etiologies of lymphedema are classified as either primary or secondary. Lymphedema is considered primary if no identifiable inciting factor led to lymphedema. It is rare (1/100,000 U.S. population) and is due to inherited or congenital malformations of the lymphatic system.4 Specific genetic defects in lymphatic vessel development have been identified, but current yield of genetic testing is low and does not change management in the majority of patients.5 Secondary lymphedema is much more common (1/1,000 U.S. population) and is due to any form of lymphatic damage that leads to impaired function.4

Worldwide, the most common cause of secondary lymphedema is infection by the parasite Wuchereria bancrofti, which causes filariasis with resultant fibrosis of the lymphatic system. In developed countries, cancer treatment is the most common cause of secondary lymphedema, affecting up to 30% of those who received axillary lymph node dissection and radiation for breast cancer.6 Interestingly, there is heterogeneity in the development of breast cancer-related lymphedema, which may be attributed to underlying genetic predisposition.7

Additional secondary insults include recurrent cellulitis, prior limb trauma and obesity.8 There is also clinical overlap in patients with chronic venous disease and lymphatic dysfunction (phlebolymphedema) and lipedema (lipo-lymphedema).

Diagnosing Lymphedema

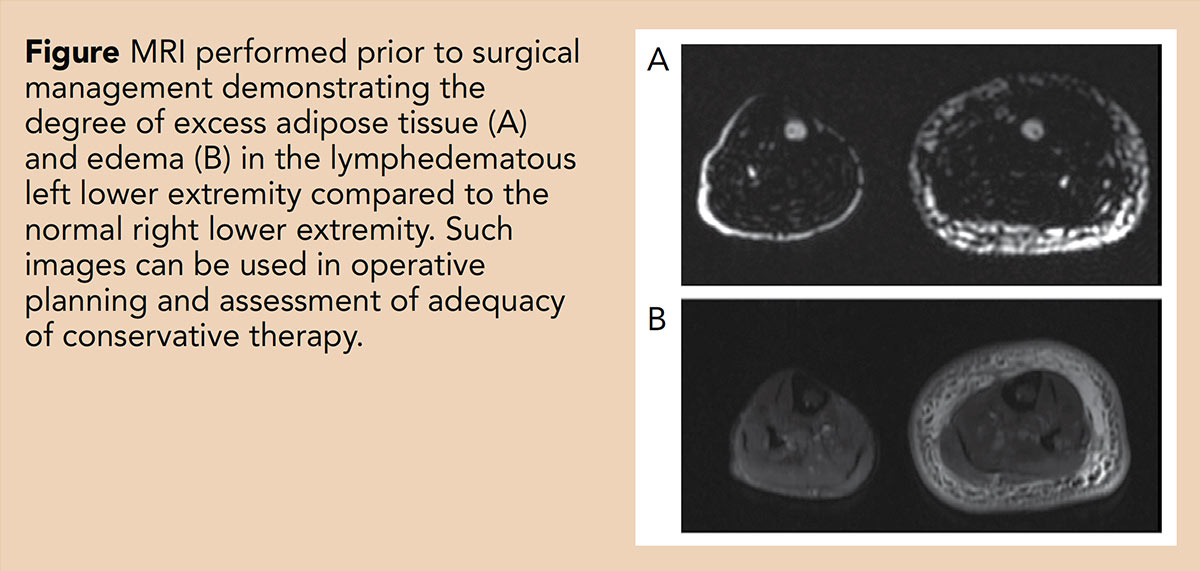

A thorough history and physical exam are necessary to diagnose lymphedema and is often sufficient to make the diagnosis of lymphedema; however, in some cases, additional imaging is necessary. The gold standard imaging to evaluate lymphatic function is nuclear lympho-scintigraphy in which radiolabeled sulfur colloid is injected subcutaneously to visualize lymphatic drainage.9 MRI and computed tomography (CT) are increasingly utilized as they are more readily available, with some studies reporting sensitivities and specificities >80%.10 Limitations include radiation exposure from CT and the injected contrast material from MRI intermixing with the venous system requiring specialized techniques to visualize the lymphatic system.11 Fluorescence imaging does not offer quantitative measurements and is currently more often used to aid in surgical planning rather than diagnosis.

Treatment Approaches

Treatment for lymphedema is guided largely on symptom management, volume reduction and infection prevention. Multidisciplinary teams have been developed and may be best poised to offer the full range of therapeutic options.12 Medications, including diuretics, have not shown to be beneficial.13

Early promise of antagonizing the inflammatory cascade of lymphedema with blockade of leukotriene B4 with bestatin did not demonstrate significant clinical reductions in symptoms.14 A small trial demonstrated reduced skin thickness in patients who received ketoprofen, but its use is limited by a black box warning of increased cardiovascular events with long-term use.15

The first line of treatment for lymphedema is conservative management. Complete decongestive therapy (CDT) has become the forefront of physiotherapeutic conservative management and is divided into two phases: decongestion, followed by maintenance. The decongestion phase is usually a four to six week program led by certified lymphedema therapists and includes MLD, compression therapy, exercise and skin care.

MLD differs from traditional massage as it focuses on redirection and promotion of lymphatic drainage via specialized, agile, repetitive movements. Compression therapy with multilayered bandaging or wraps are applied after manual lymph drainage. Exercise therapy involves gentle, repetitive contraction of the affected limb and skin care is important to prevent cellulitis, the most common complication of lymphedema.

Although there are no randomized clinical trials, small observational studies have shown MLD to be beneficial at reducing lymphedema-associated swelling, particularly in combination with compression therapy.16–20

Once limb volume reduction is achieved, patients graduate to the maintenance phase by performing these routines on their own. Ongoing adherence to well-fitted compression garments is essential to maintain the reduction that was obtained with CDT. Custom, flat-knit garments can often be most beneficial to maintain prior reductions in edema, but these can be expensive and not routinely covered by insurance.

Intermittent pneumatic compression devices can also be utilized; however, there is some controversy regarding their overall benefit.21,22 Some patients find pneumatic devices to be helpful at reducing edema, though the effects tend to last only a few hours and work best when used in conjunction with regular, high-quality compression. Notably, pneumatic pumps demonstrated a reduction in cellulitis in a claims-based dataset.23

In addition to compression options, exercise and weight loss can be beneficial.24 Lymphedema can be caused from obesity directly, but in all patients, maintenance of a healthy weight can have dramatic improvements in control of lymphedema.

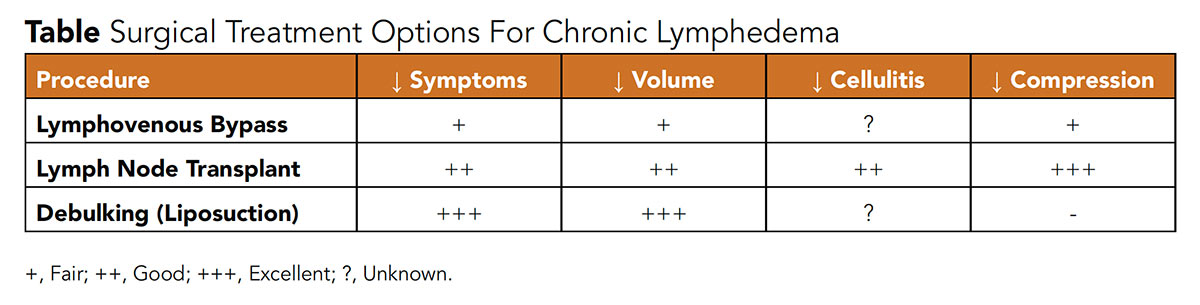

Surgical Treatment Approaches

If significant symptoms persist despite good adherence to conservative management, evaluation at a lymphatic surgical center can be considered. Lymphatic to venous anastomoses (LVA, or lympho-venous bypass) and vascularized lymph node transfer (VLNT) are the two functional/physiological surgeries used for treatment.25

LVA creates shunts for lymphatic fluid to utilize the venous system as a primary transport back to the heart and "bypass" potential obstruction, like the axilla in patients with prior breast cancer treatment. VLNT involves an autologous transplant of a pedicle of lymph nodes (deep inferior epigastric artery perforator and superficial inguinal lymph node flaps are commonly used for breast cancer-related lymphedema) to the affected limb. The exact mechanism by which lymphedema is improved with this method is unclear, however, hypotheses include stimulation of lymphangiogenesis with drainage via the implanted pedicle or development of new lymphatic collateral pathways connecting adjacent lymph nodes to restore outflow.26

LVA and VLNT have both demonstrated improvement in quality of life, decreased need for compression, and modest reductions in volume, though most data reflect single-center case series.27 There has yet to be a robust comparison of the two.28,29 In a small study of 17 patient by Cheng, et al, VLNT, compared with LVA, had greater lymphatic volume reduction (6.6±5.9 kg and 1.7±0.6 kg, p<0.05) and significant improvement in their lymphedema quality of life score (from 3.9±1.2 to 6.4±1.1, p<0.05).30

LVA is increasingly performed at the time of high-risk lymph node dissection as a prophylactic measure to decrease the development of lymphedema (Lymphatic Microsurgical Preventative Healing Approach [LYMPHA] study); early data demonstrate promise, but more investigation is required.31

Physiologic procedures focus on improving lymphatic transit and decreasing edema, but for most patients with more advanced lymphedema, there is significant adipose deposition that contributes to increased limb girth that will not improve with compression or physiologic procedures. For such patients, ablative/debulking surgeries are an option to remove excess adipose tissue.

Direct excisional procedures have largely been replaced with power-assisted liposuction given prior morbidity with excisional surgeries. In a prospective study in 116 women with breast cancer-related lymphedema who underwent liposuction, 15-year follow-up showed promising results with all women having complete resolution of their lymphedema without recurrence.32

There are small series that also demonstrate benefit in patients with lower extremity lymphedema, including those with primary lymphedema.33 Though dramatic decreases in limb girth can be achieved, compression essentially 24 hours a day is required to maintain volume reduction. Debulking procedures have been performed simultaneously or with subsequent VLNT to potentially decrease need for compression, but data remain limited.

Team-Based Care

As lymphedema is a chronic, incurable disease that affects patients' physical and mental well-being, a multidisciplinary approach to patient management is important. Such teams may include providers from physical rehabilitation, vascular medicine, plastic surgery, radiology, oncology, infectious disease and social work. Such teams can offer thorough evaluation to assess the etiology of limb swelling, optimize conservative care and offer surgical treatment for appropriate candidates. Additionally, recognition of lymphedema's significant morbidity, decrease in quality of life and potential treatment options by providers is important to optimize patient care as more is learned about this relatively poorly understood disease process.

This article was authored by Varayini Pankayatselvan, MD, resident in internal medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), and Brett J. Carroll, MD, director, Section of Vascular Medicine, Division of Cardiology, BIDMC, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School.

References

- Son A, O'Donnell TF Jr, Izhakoff J, et al. NESVS5. Lymphedema comorbidities and treatment rate in the United States. J Vasc Surg 2018;68:e99.

- Jiang X, Nicolls MR, Tian W, Rockson SG. Lymphatic dysfunction, leukotrienes, and lymphedema. Annu Rev Physiol 2018;80:49-70.

- Rockson SG, Keeley V, Kilbreath S, et al. Cancer-associated secondary lymphoedema. Nat Rev Dis Prim 2019;5:1-16.

- Rockson SG, Rivera KK. Estimating the population burden of lymphedema. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1131:147-54.

- Gordon K, Varney R, Keeley V, et al. Update and audit of the St George's classification algorithm of primary lymphatic anomalies: a clinical and molecular approach to diagnosis. J Med Genet 2020;57:653-9.

- Cormier JN, Askew RL, Mungovan KS, et al. Lymphedema beyond breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cancer-related secondary lymphedema. Cancer 2010;116:5138-49.

- Miaskowski C, Dodd M, Paul SM, et al. Lymphatic and angiogenic candidate genes predict the development of secondary lymphedema following breast cancer surgery. PLoS One 2013;8(4).

- Greene AK. Diagnosis and management of obesity-induced lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 2016;138:111e-118e.

- Bernas M, Thiadens SRJ, Smoot B, et al. Lymphedema following cancer therapy: overview and options. Clin Exp Metastasis 2018;35:547-51.

- Monnin-Delhom ED, Gallix BP, Achard C, et al. High resolution unenhanced computed tomography in patients with swollen legs. Lymphology 2002;35:121-8.

- Ripley B, Wilson GJ, Lalwani N, et al. Initial clinical experience with dual-agent relaxation contrast for isolated lymphatic channel mapping. Radiology 2018;286:705-14.

- Johnson AR, Fleishman A, Tran BNN, et al. Developing a lymphatic surgery program: a first-year review. Plast Reconstr Surg 2019;144:975e-985e.

- Cemal Y, Pusic A, Mehrara BJ. Preventative measures for lymphedema: Separating fact from fiction. J Am Coll Surg 2011;213:543-51.

- Tian W, Rockson SG, Jiang X, et al. Leukotriene B4 antagonism ameliorates experimental lymphedema. Sci Transl Med 2017;9(389).

- Rockson SG, Tian W, Jiang X, et al. Pilot studies demonstrate the potential benefits of antiinflammatory therapy in human lymphedema. JCI Insight 2018;3(20).

- Lee JH, Shin BW, Jeong HJ, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of therapeutic effects of complex decongestive therapy in breast cancer-related lymphedema. Ann Rehabil Med 2013;37:683-89.

- Tan I-C, Maus EA, Rasmussen JC, et al. Assessment of lymphatic contractile function after manual lymphatic drainage using near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92:756-64.e1.

- Zasadzka E, Trzmiel T, Kleczewska M, Pawlaczyk M. Comparison of the effectiveness of complex decongestive therapy and compression bandaging as a method of treatment of lymphedema in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging 2018;13:929-34.

- Armer JM, Hulett JM, Bernas M, et al. Best practice guidelines in assessment, risk reduction, management, and surveillance for post-breast cancer lymphedema. Curr Breast Cancer Rep 2013;5:134-44.

- Fu MR, Deng J, Armer JM. Putting evidence into practice: cancer-related lymphedema. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2014;18 Suppl:68-79.

- Lerman M, Gaebler JA, Hoy S, et al. Health and economic benefits of advanced pneumatic compression devices in patients with phlebolymphedema. J Vasc Surg 2019;69:571-80.

- Tran K, Argáez C. Intermittent pneumatic compression devices for the management of lymphedema: a review of clinical effectiveness and guidelines. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2017. Available here. Accessed Feb. 17, 2021.

- Karaca-Mandic P, Hirsch AT, Rockson SG, Ridner SH. The cutaneous, net clinical, and health economic benefits of advanced pneumatic compression devices in patients with lymphedema. JAMA Dermatol 2015;151:1187-93.

- Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel A, et al. Weight lifting in women with breast-cancer–related lymphedema. N Engl J Med 2009;361:664-73.

- Garza R, Skoracki R, Hock K, Povoski SP. A comprehensive overview on the surgical management of secondary lymphedema of the upper and lower extremities related to prior oncologic therapies. BMC Cancer 2017;17:468.

- Joseph WJ, Aschen S, Ghanta S, et al. Sterile inflammation after lymph node transfer improves lymphatic function and regeneration. Plast Reconstr Surg 2014;134:60-8.

- Basta MN, Gao LL, Wu LC. Operative treatment of peripheral lymphedema: a systematic meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of lymphovenous microsurgery and tissue transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:905-13.

- Scaglioni MF, Fontein DBY, Arvanitakis M, Giovanoli P. Systematic review of lymphovenous anastomosis (LVA) for the treatment of lymphedema. Microsurgery 2017;37:947-53.

- Scaglioni MF, Arvanitakis M, Chen Y-C, et al. Comprehensive review of vascularized lymph node transfers for lymphedema: Outcomes and complications. Microsurgery 2018;38:222-29.

- Cheng M-H, Loh CYY, Lin C-Y. Outcomes of vascularized lymph node transfer and lymphovenous anastomosis for treatment of primary lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2018;6(12).

- Hahamoff M, Gupta N, Munoz D, et al. A lymphedema surveillance program for breast cancer patients reveals the promise of surgical prevention. J Surg Res 2019;244:604-11.

- Brorson H. Liposuction in lymphedema treatment. J Reconstr Microsurg 2015;32(01):56-65.

- Granoff MD, Johnson AR, Shillue K, et al. A single institution multi-disciplinary approach to power-assisted liposuction for the management of lymphedema. Ann Surg 2020;Nov 4:{Epbub ahead of print].

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia, Noninvasive Imaging, Prevention, Lipid Metabolism, Computed Tomography, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Nuclear Imaging, Exercise

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Adipose Tissue, Autografts, Axilla, Breast Neoplasms, Cardiovascular Diseases, Cellulitis, Colloids, Communicable Diseases, Contrast Media, Developed Countries, Diuretics, Drug Labeling, Edema, Epigastric Arteries, Exercise Therapy, Fibrosis, Filariasis, Follow-Up Studies, Genetic Predisposition to Disease, Genetic Testing, Homeostasis, Intermittent Pneumatic Compression Devices, Insurance, Internal Medicine, Ketoprofen, Leukotriene B4, Lipectomy, Lower Extremity, Lymph Node Excision, Lymph Nodes, Lymphangiogenesis, Lymphangiogenesis, Lymphatic System, Lymphatic Vessels, Lymphedema, Lymphoscintigraphy, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Maintenance, Morbidity, Obesity, Optical Imaging, Patient Care, Patient Care Team, Parasites, Prevalence, Prospective Studies, Quality of Life, Radiation, Radiology, Reference Standards, Schools, Medical, Skin Care, Social Work, Sulfur, Surgery, Plastic, Tomography, Tomography, X-Ray Computed, Weight Loss, Wuchereria bancrofti

< Back to Listings