Conversations With Experts | Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Post PCI: When and How to De-Escalate

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after PCI is a fast-evolving area, with a clear focus on optimizing the duration. Where do we stand today? What do the guidelines tell us and how do we put this into practice? And when and how is it appropriate to de-escalate DAPT?

Cardiology Editor-in-Chief Peter C. Block, MD, FACC, and Roxana Mehran, MD, FACC, a leading expert in interventional cardiology, explore answers to these questions as they relate to the patient case here.

Peter C. Block MD, FACC

Roxana Mehran MD, FACC

The Case

A 68-year-old man (nonsmoker, nondiabetic, hyperlipidemic) was admitted to the cardiology department three months ago with nonspecific chest discomfort. His ECG was normal and hs-Troponin negative.

The patient is a cardiologist and insisted on a coronary angiography, which was performed with preprocedural aspirin + clopidogrel. Results showed a 95% stenosis in the mid to distal portion of the LAD. LAD branches S1 and D1 were atheromatous up to 10%, going distal just before S3 atheromatous up to 25%. D1 branch mid segment stenosis with up to 50% diameter reduction. The right coronary artery (RCA) was small and there was a co-dominant circumflex with several nonsignificant atherosclerotic changes.

A PCI was performed with a 2.5 x 18 mm drug-eluting stent (everolimus).

Postprocedural therapy was aspirin 100 mg, clopidogrel 150 mg, rosuvastatin 40 mg, metoprolol 50+25+25 mg and trimetazidine SL 80 mg. On Day 2 post procedure, DAPT was reloaded with prasugrel 60 mg and continued aspirin 100 mg plus prasugrel 10 mg.

A reactive test was performed after three months and the patient was almost a hyper-responder.

Hyper-response to DAPT is associated with increased risk of hemorrhagic complications.

Mehran: Based on the presentation, this is single-vessel disease but with some atherosclerosis. It does not appear this patient had an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) as he presented with nonspecific chest discomfort and did not have a myocardial infarction (MI). On Day 2 post procedure, the patient was given prasugrel, although the indication for this is not clear. This patient is now a hyper-responder, so I would de-escalate DAPT. Therapy could be changed to aspirin plus clopidogrel without the need of a loading dose.

In my mind, the big question for this patient is how long is DAPT needed? His bleeding risk is key to answering this, so I would take a much more in-depth history to identify factors that would place him at a higher risk for bleeding complications. For example, does he have cancer? Chronic kidney disease? What's his hemoglobin? If he is at higher risk, I would abbreviate the duration of DAPT.

The next big question is what drug should be used for single antiplatelet therapy? Data are building on the use of clopidogrel/P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy. In fact, the new ACC/AHA guideline on coronary artery revascularization includes a class 2A recommendation for P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy for single antiplatelet therapy. This new recommendation could fit for this patient, depending on how he does during the time he is on DAPT.

Block: How is de-escalation handled? How long should DAPT be continued before it would be safe to de-escalate? Does this time frame differ for a patient who had an ACS? What drug should be used?

Mehran: Great questions. If this patient truly had suffered an ACS, I would give the more potent agent. And if his bleeding risk was low, I would continue up to 12 months.

Block: Does this mean that de-escalation is moot for a patient with an ACS?

Mehran: No, I don't think it's moot, because of the variables in the equation to make the decision about whether it's appropriate to de-escalate in a particular patient. And it's important to note that this determination about whether to de-escalate therapy is not done just once – continued surveillance is required.

Some of variables for the equation include whether the patient is tolerating DAPT; whether a staged procedure is needed; and if there was a bleed when the potent agent was part of the DAPT. For a patient who is a hyper-responder on prasugrel 10 mg, you may need to consider if it's possible to reduce to 5 mg should there be concern about bleeding. There are many permutations and clearly one size does not fit all. Vigilance is needed.

Block: With every patient being a little different and there being a need to tailor treatment to fit the specific patient (as well as changes needed over time), how do you on a practical level monitor your patients? How often do you see them or do you call them?

Mehran: I see every patient about one or two weeks after their PCI to make sure the access site is doing well, their prescription was filled and they are taking the medication. I also use this time to answer any questions they may not have thought of when they were in the hospital.

I see the patient again a month after the procedure, which is good timing to evaluate whether they are having bruising and whether they are tolerating the medication or any adjustments are needed. For example, if a patient on ticagrelor is having shortness of breath.

The first month after the PCI is the most crucial time. It's when the most bleeding and ischemic events occur. This is why I see every patient twice during this first month. Thereafter, I see a patient at either three or four months, and sometimes even six months depending on their level of risk. If a patient is really high risk or not adherent, I may see them more often.

Online patient portals like MyChart offer increased opportunities to converse with patients more frequently and address issues or questions as they arise. They also allow for easy sharing of education materials along the way.

Block: Let's say I send a patient to you who is at relatively low risk who did not have an ACS. Then you find a stent is needed because of ischemia with an FFR of 0.65. In terms of individualizing treatment, for this low-risk patient, what's the shortest duration of either single or dual antiplatelet therapy? And how long would you follow this patient before you "discharge" them from follow-up?

Mehran: For a patient with a proximal lesion in the left anterior descending with a chronic coronary syndrome and a low risk for bleeding, I'd keep them on DAPT for at least six months.

If the patient is low risk in terms of thrombotic events, but I'm concerned about a potential bleeding event because of anemia or some other variable, I'll go as short as one month. Then I'd evaluate the patient and I may switch to P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy.

Block: Data now support the safety of a single antiplatelet agent for just a month in this specific scenario, correct? This is really cutting down on the duration of antiplatelet therapy after an intervention.

Mehran: If I had a patient, for example, who had a left main bifurcation stent and I wanted to move from aspirin plus clopidogrel to a single antiplatelet agent, I'd probably get a platelet function test first to make sure they respond to clopidogrel. For nonresponders to clopidogrel, I'd probably switch the patient to prasugrel or ticagrelor and then move to monotherapy with one of these two drugs.

There are so many different permutations and we need to put all the variables into perspective. Unfortunately, we don't have data to guide us for all of the different permutations we'll see in practice and then we have to rely on our common sense and wisdom.

DAPT Duration in ACS Post PCI: What the Guidelines Say

The default duration for dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for a patient with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) treated by PCI is 12 months in both the 2016 ACC/American Heart Association (AHA) Focused Update on DAPT and in the 2017 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Focused Update on DAPT.1,2

DAPT with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor is typically recommended regardless of the type of stent implanted, but if no contraindications exist, ticagrelor or prasugrel should be used in preference to clopidogrel for maintenance therapy.

DAPT prolongation can be considered in patients who have tolerated it well and are not at high risk for bleeding, whereas discontinuation at six months should be considered for those who are at high bleeding risk or who develop significant overt bleeding.

It should be noted, however, that both of these guidelines were written before newer trials on DAPT de-escalation and P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy in ACS patients became available.3 The newer 2021 ACC/AHA/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization updates the post-PCI DAPT in ACS recommendation thus: "In selected patients undergoing PCI, shorter-duration DAPT (one to three months) is reasonable, with subsequent transition to P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy to reduce the risk of bleeding events."4

The 2021 guideline writers explain that pooled data from a number of trials completed since 2016 that tested shorter-duration DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy after PCI have demonstrated significantly less bleeding with shorter-term DAPT (three to six months) and fewer ischemic events (including stent thrombosis) with longer-term DAPT (>12 months).

Among the studies not referenced in either the 2016 ACC/AHA or 2017 ESC guidelines are several trials testing switching or de-escalation of DAPT potency, platelet function testing and genotyping.3

Various DAPT de-escalation strategies have been evaluated in several ACS-PCI trials. De-escalation is usually defined as switching from a full-dose potent to a reduced dose or less potent P2Y12 inhibitor, which may be from ticagrelor or prasugrel to clopidogrel or by reducing the dose of ticagrelor or prasugrel.

A 2021 meta-analysis pooled data from five trials including 10,799 patients assigned to different DAPT de-escalation strategies: genetically-guided to clopidogrel (n=1,242); guided by platelet function testing to clopidogrel (n=1,304); unguided to clopidogrel (n=1,672); unguided to lower dose P2Y12 inhibitor (n=1,170); or standard DAPT (control group, n=5,391).5 Aspirin monotherapy trials were excluded.

DAPT de-escalation was associated with a significant reduction in bleeding (BARC ≥2; hazard ratio [HR], 0.57; I2 = 77%). This result was consistent with both unguided (HR, 0.44, p<0.05; I2 = 34%) and guided de-escalation (HR, 0.79, p<0.05; I2 = 0%) strategies.

Major adverse cardiac events (in most trials defined as the composite of cardiovascular mortality, MI, stent thrombosis and stroke) were also significantly reduced with DAPT de-escalation vs. standard therapy (HR, 0.77, p<0.05).

The authors concluded that de-escalation of DAPT after ACS-PCI, whether guided by genetic or platelet testing or unguided, "was associated with lower rates of clinically relevant bleeding and ischemic events as compared to standard DAPT with potent P2Y12 inhibitors based on five open-label RCTs reviewed."

References

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:1082-1115.

- Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: The Task Force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2018;39:213-260.

- Capodanno D, Alfonso F, Levine GN, et al. ACC/AHA versus ESC guidelines on dual antiplatelet therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72(23_Part_A):2915-2931.

- Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:e21-e129.

- Tavenier AH, Mehran R, Chiarito M, et al. Guided and unguided de-escalation from potent P2Y12 inhibitors among patients with acute coronary syndrome: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2021;Aug 31:[Epub ahead of print].

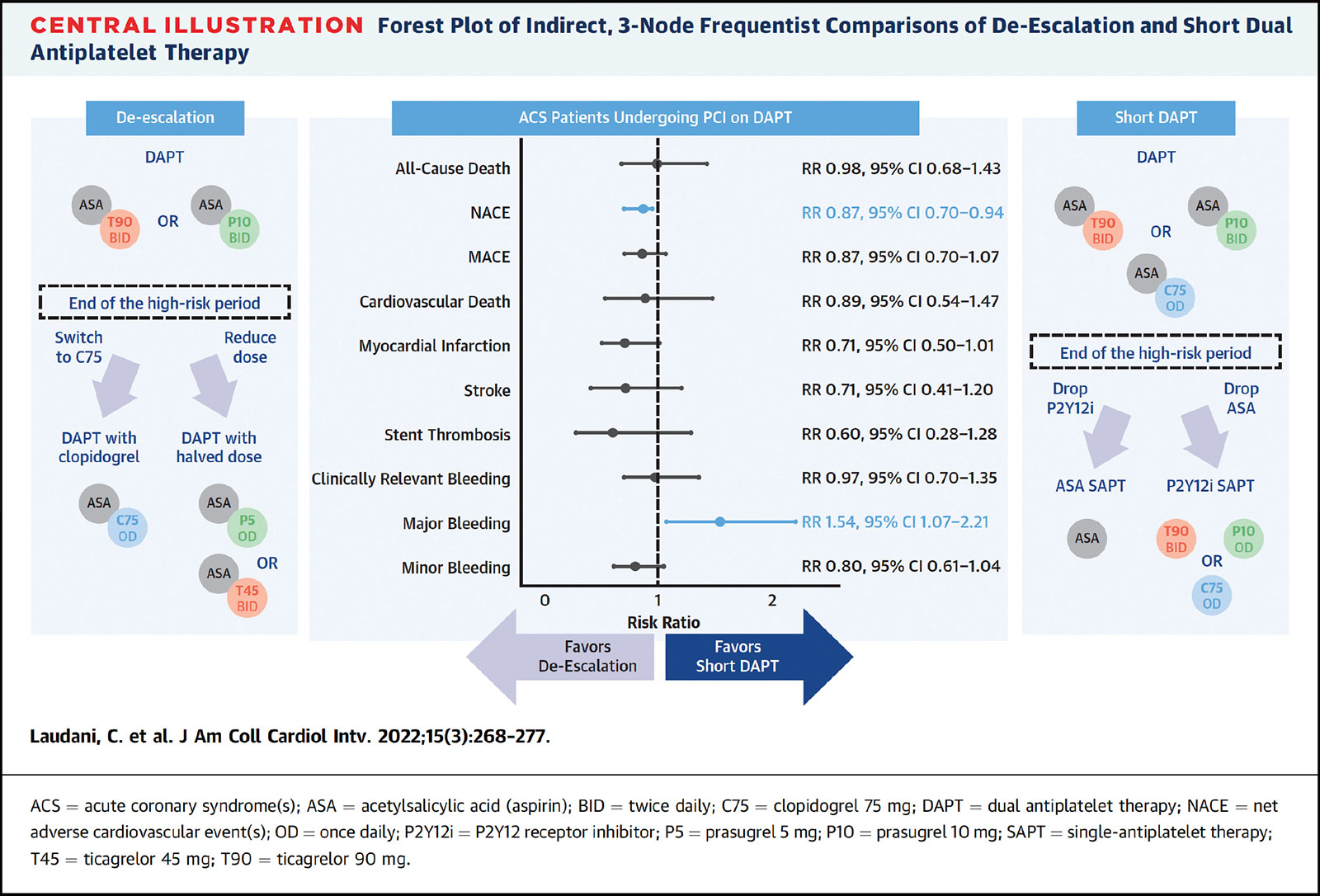

Short-Term DAPT vs. De-Escalation

To reduce the risk of major bleeding (and subsequent increased mortality) associated with DAPT, two strategies have been proposed. Both seek to strike a balance between providing sufficient protection from thrombosis at the stented site or nonstented coronary segments and reducing bleeding risk.

The first option, which has been tested extensively, is short-term DAPT, accomplished by discontinuing aspirin or the P2Y12 inhibitor at one, three or six months post PCI. The second option is DAPT de-escalation, switching to clopidogrel or reducing the dose of prasugrel or ticagrelor.

A number of studies (and meta-analyses) have shown the benefit of short-term DAPT or de-escalation to standard (12-month) DAPT, but no studies have directly compared short DAPT to de-escalation.

In response to this void, Claudio Laudani, MD, and Davide Capodanno, MD, PhD, both from the University of Catania in Catania, Spain, and colleagues, conducted an indirect comparison of short DAPT and de-escalation that was recently published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.1

Using standard DAPT as the comparison, they identified 29 studies encompassing 50,602 patients with ACS who underwent PCI and received either shortened DAPT (vs. standard DAPT) or de-escalating DAPT to a lower potency regimen (vs. standard DAPT).

All-cause death did not differ between the two strategies (risk ratio [RR], 0.98; p=NS). De-escalation (indirectly) compared with shortened DAPT reduced the risk for net adverse cardiovascular events (NACE) with a risk ratio of 0.87 (p<0.05), but increased the risk of major bleeding (RR, 1.54; p<0.05).

"De-escalation displayed a >95% probability to rank first for NACE, MI, stroke, stent thrombosis, and minor bleeding, while short DAPT ranked first for major bleeding," write Laudani, et al.

The findings were consistent across 28 different sensitivity analyses, and also consistent for all study outcomes, including cardiovascular death, MI, clinically-relevant bleeding and minor bleeding.

Current European guidelines give a Class 2a recommendation to shortening the duration of DAPT and a Class 2b recommendation to de-escalation. "Our results challenge this ranking, as DAPT de-escalation showed a similar risk for death and a reduced risk for NACE – 2 measures of overall net benefit – compared with short DAPT," write Laudani and colleagues. They suggest the two options should be, "if anything," given the same class of recommendation.

In an accompanying editorial, Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, FACC, and Robert W. Yeh, MD, MSc, FACC, note that not all short DAPT and de-escalation strategies are created equal, as evidenced by one of the sensitivity analyses where the risk of stent thrombosis appeared to be highest following a short DAPT regimen with extended aspirin monotherapy and lowest following de-escalation to half-dose prasugrel/ticagrelor.2

They conclude that both options are "equally viable (Class 2a) alternative strategies to the current (one year) recommendation based on bleeding/ischemic risk stratification." They suggest clinicians "strongly consider de-escalation strategies that may be an important intermediate path between standard DAPT regimens and very short DAPT duration."

References

- Laudani C, Greco A, Occhipinti G, et al. Short duration of DAPT versus de-escalation after percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2022;15:268-77.

- Kereiakes DJ, Yeh RW. DES and DAPT in evolution. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2022;15:278-81.

Visit ACC.org/Guidelines to access clinician and patient resources tied to the newest guidelines for Chest Pain and Coronary Artery Revascularization.

Clinical Topics: Acute Coronary Syndromes, Cardiovascular Care Team, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Noninvasive Imaging, Interventions and ACS, Interventions and Imaging, Angiography, Nuclear Imaging

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Acute Coronary Syndrome, American Heart Association, Anemia, Angiography, Aspirin, Atherosclerosis, Cardiologists, Cardiology, Clopidogrel, Constriction, Pathologic, Control Groups, Coronary Angiography, Coronary Vessels, Drug-Eluting Stents, Dyspnea, Electrocardiography, Everolimus, Follow-Up Studies, Follow-Up Studies, Fractional Flow Reserve, Myocardial, Genotype, Hemoglobins, Hemorrhage, Hospitals, Ischemia, Metoprolol, Myocardial Infarction, Neoplasms, Non-Smokers, Patient Discharge, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Platelet Aggregation Inhibitors, Prasugrel Hydrochloride, Renal Insufficiency, Chronic, Stents, Stroke, Thrombosis, Ticagrelor, Troponin

< Back to Listings