Feature | Peeling Back the Layers: Understanding CV Health in Asian American Communities

When Latha P. Palaniappan, MD, MS, FACC, professor of medicine at Stanford University, was 13, her dad, then 39, died from a heart attack. So it made sense that when she went to medical school, Palaniappan, who is South Asian, started looking into the risk of heart disease in Asian Americans. Everything she read, however, showed that Asian Americans were less likely to die of heart disease than any other ethnicity. "I thought, 'that's surprising,'" she says.

Indeed, the age-adjusted mortality rate attributable to cardiovascular disease in the U.S. is highest in Black males (379.7 per 100,000), with the lowest rate in Asian females (104.9 per 100,000), according to 2022 statistics.1 Overall, there is a 51.5% and 38.5% total cardiovascular disease prevalence in Asian males and females respectively, compared with 52.4% and 44.9% for all males and females, respectively.

In digging into this further, Palaniappan and others found wide disparities in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality rates based on country of origin, however, U.S. health data (until recently) categorized Asians as one ethnic category masking these differences.

In reality, there are about 40 distinct Asian groups in the US. Among the largest are East Asians, which includes Chinese, Japanese and Korean individuals; South Asians, which includes those from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Bhutan; and Southeast Asians, which includes those from Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam.2

East Asians account for the largest portion of the Asian American population and have lower risks of heart disease compared with Southeast Asians, who make up a smaller number; ultimately skewing the data.

For instance, while ischemic heart disease mortality significantly decreased in Chinese, Filipino, Japanese and Korean men, as well as non-Hispanic whites and Hispanic men, between 2003 and 2017, it remained stagnant in Asian Indian and Vietnamese men, with the highest mortality rate in 2017 among Asian Indian women (77 per 100,000) and men (133 per 100,000). There were also significant disparities in deaths from heart failure and stroke based on Asian subgroup.3

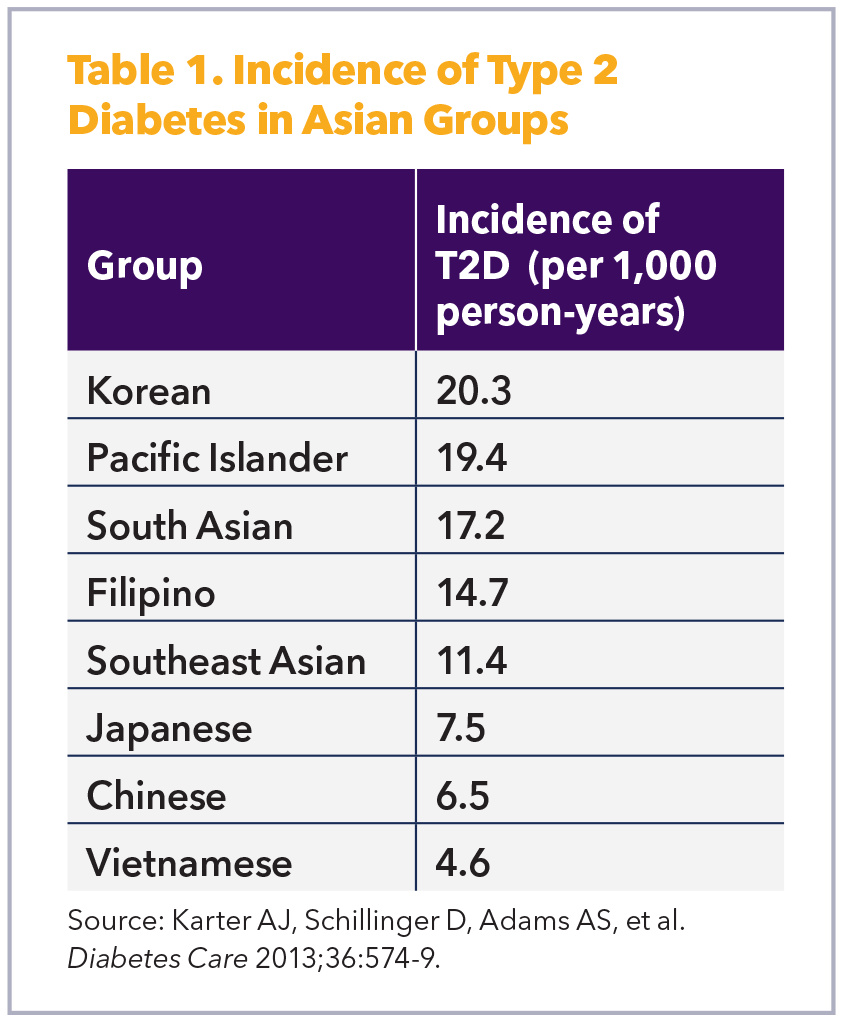

There are also significant differences in cardiovascular risk factors. As Table 1 shows, there is wide disparity in the incidence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) among Asian-American subgroups.4

Obesity rates also vary, with the highest among Filipino, Japanese and Asian Indian individuals and the lowest among Chinese individuals. Similarly, hypertension rates are highest in Asian Indians (37%) compared with Chinese (21%).5-7 In addition, while national smoking prevalence in the Asian American population from 2013 to 2015 was 9.4% overall, it was 19.4% in Japanese Americans, 18.9% in Vietnamese Americans and 18.8% in Korean Americans compared with a low of 13.3% among Chinese Americans.8

Lim, et al., found that Asian Indians born outside the U.S. had a significantly higher prevalence of diabetes, physical inactivity and overweight/obesity compared with other groups; while Chinese Americans had a higher prevalence of physical inactivity. Filipino Americans born outside the U.S. had a higher prevalence of all five cardiovascular disease risk factors except smoking compared with non-Hispanic White adults.9 There are even subgroup differences in sleep duration and its association with cardiovascular disease.10

An analysis of 3.5 million patient years (2008-2018) found that cardiovascular disease prevalence increased more slowly among Japanese and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islanders compared with other Asian groups. Specifically, the prevalence of cardiovascular disease in Filipinos rose from 34.3% to 45.1%, while the prevalence in Asian Indians grew fastest (16.9% to 23.7%). Filipinos had the highest prevalence of hypertension, which rose from 31.8% to 41.2% during the 10-year period.11

"Southeast Asian Indians are really plagued with premature coronary disease while Asian Americans from Japan, China, Korea and Taiwan, as well as Southeast Asians from Thailand and Vietnam, have higher rates of stroke," says James C. Fang, MD, FACC, chief of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Utah School of Medicine in Salt Lake City. This stark contrast in disease patterns demands tailored approaches to prevention, diagnosis and treatment, he says.

The "Model Minority" Myth

There are three main stereotypes underlying the grouping of all Asians as one that does not experience health disparities. The "model minority myth" portrays Asian Americans as a monolithic group with universally high levels of education, income and health outcomes, while the "healthy immigrant effect" suggests that immigrants are healthier than native-born Americans regardless of social determinants of health like employment status, income level and housing security. The "perpetual foreigner" also wrongly posits that Asian immigrants never fully assimilate into American culture regardless of their length of time in the U.S. and which manifests as overt racism.13

"When people have looked at issues around the health of minority populations, Asian people have tended not to be part of that conversation," says Eugene Yang, MD, MS, FACC, professor of medicine, who holds the Carl and Renée Behnke Endowed Chair for Asian Health at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. "I think there's this concept of the 'model minority' that extends beyond just the fact that Asian American individuals are viewed as being more educated and wealthier. There's also a perception, by extension, that perhaps they're healthier."

James Floyd, MD, MS, a physician-epidemiologist and professor of medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle, agrees. "There's this idea that Asians don't need help, they're doing great, we don't have to study them," he says. "Part of the reason we think Asians are healthy or they don't have problems is because they might not complain and nobody wants to ask. Nobody's actually taking the effort to rigorously and systematically study them."

Now that's about to change.

The MOSAAIC Study: A Major Step Forward

To address these critical knowledge gaps, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute has funded a seven-year, $38.7 million observational study called MOSAAIC (Multi-Ethnic Observational Study in American Asian and Pacific Islander Communities), the first such study the institute has ever funded. "For decades, people have wanted a cohort focused on Asian Americans but there just hasn't been any traction," says Floyd, who is one of four principal investigators leading the study's coordinating center.

The MOSAAIC study will recruit 10,000 participants from five U.S. field centers focusing on six of the most populous Asian American subgroups in the U.S.: Chinese Americans, Korean Americans, Vietnamese Americans, Filipino Americans, Indian Americans and Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders.

While Floyd notes that factors like language, low socioeconomic status, lack of health insurance and access to health providers provides some unique recruiting challenges, he is hopeful that recruiting all these groups using the same methods and using a rigorous, standardized protocol will actually allow for valid comparisons of disaggregated Asian populations.

"Individuals who don't speak English are often missed by recruitment efforts," he says. "To reach them, you can't just put up flyers and knock on a few doors. You have to partner with community organizations and use community-based methods, which is the approach we are using in MOSAAIC."

The core examination will include extensive surveys covering cardiovascular health, mental health, social determinants of health, and detailed pulmonary and sleep health questionnaires. Researchers will also collect biospecimens (blood, urine, saliva, stool) and perform basic clinical measures including anthropometry, electrocardiograms and spirometry with bronchodilator challenges.

"Prospective cohort studies like this are engines for scientific discovery," says Floyd. "I'm thrilled to be involved in a study that is large enough to really understand how health behaviors, health risks and perhaps even biological mechanisms differ among the richly diverse Asian American communities."

Looking Forward: A Precision Medicine Approach

As research advances, Palaniappan envisions a future where precision medicine transforms the care of Asian-American patients. "I'm very excited for the day that they'll look back and they'll say it was so archaic to look at race and ethnicity when you can look at genetic-derived markers of ancestry," she says.

She predicts that genetic testing will eventually become routine in cardiovascular care. "The cost of genetic testing is coming down rapidly, and I think that it will be within our lifetimes that every patient will have a genetic test that informs their disease prediction, progression, treatment, prevention."

In the meantime, she says, clinicians must recognize that Asian Americans are not a monolith. "South Asians need earlier screening for heart disease, while Filipinos require aggressive hypertension management," says Palaniappan. "Culturally tailored, ethnicity-specific care is crucial to achieve positive health outcomes for all."

The Leadership Gap: Breaking Through the "Bamboo Ceiling"

Despite making up approximately 25% of medical school students in the U.S., Asian Americans remain significantly underrepresented in leadership positions within health care systems and academic medical centers.1 They are also less likely to be promoted to tenured positions or full professorships compared with their non-Asian counterparts, despite holding tenure-eligible positions.2 Asian researchers are also less likely to receive National Institutes of Health R01 grants than non-Hispanic White researchers even when they have more publications and citations on their resumes.3,4

Indeed, a recent study measuring whether a group's representation in leadership matched their representation at faculty levels found that Asian faculty members were consistently underrepresented in leadership positions such as department chairs and deans despite having good representation at faculty levels, with Asian women facing the greatest disparity.1

"There's a term called the bamboo ceiling," says Eugene Yang, MD, MS, FACC. "Asians only achieve a certain level of leadership because there's a ceiling that prevents them from achieving higher levels of leadership opportunities."

Several factors contribute to this leadership gap, says Yang. "One is the lack of representation of people who are in these positions to mentor others to achieve similar leadership positions. If you don't have people who look like you or who have similar backgrounds, then you don't see role models to help you achieve that goal of becoming a division head or department chair or dean of a medical school."

Another is that health equity and diversity efforts tend to focus on specific minoritized populations, Yang says. "Because of our over-representation in medical schools and residency training programs, these efforts have not really focused on Asian Americans."

However, studies have shown that Asians face similar challenges to other minority groups in academic medicine, such as structural and organizational barriers, communication issues (among first-generation Asians), and discrimination, as well as the lack of mentors and role models.5-7

The "model minority" myth, which portrays Asian Americans as a monolithic group with universally high levels of education, income and health outcomes, has also been used to deny the existence of institutional racism and to pit minority groups against each other.8

Specialized centers like the one that Yang is launching this spring might help. The Asian Health Research Center at the University of Washington will focus on four key areas: research, education, mentorship and community engagement. It aims to "create a generation of researchers and investigators who want to have careers dedicated to improving Asian health," Yang says, while also educating and engaging the surrounding Asian communities to disseminate information about Asian health issues and the need for them to participate in research.

But a big part of the center is to provide mentorship, he says. "Centers like ours are vital in paving the way for greater representation of Asian American leaders in medicine."

References

- Samuel A, Soh MY, Durning SJ, et al. Parity representation in leadership positions in academic medicine: a decade of persistent under-representation of women and Asian faculty. BMJ Leader 2023;7(Suppl 2):e000804. doi:10.1136/leader-2023-000804

- Lin ME, Razura DE, Luu NN, et al. Understanding the representation of Asians and Asian Americans within academic otolaryngology leadership. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2025;172(2):500-508.

- Meixiong J, Golden SH. The US biological sciences faculty gap in Asian representation. J Clin Invest 2021;131(13) doi:10.1172/jci151581

- Ginther DK, Schaffer WT, Schnell J, et al. Race, ethnicity, and NIH Research Awards. Science 2011;333(6045):1015-1019.

- Ajayi AA, Rodriguez F, de Jesus Perez V. Prioritizing equity and diversity in academic medicine faculty recruitment and retention. JAMA Health Forum 2021;2(9):e212426-e212426.

- Albert MA. #Me_who anatomy of scholastic, leadership, and social isolation of underrepresented minority women in academic medicine. Circulation 2018;138(5):451-454.

- Zhang L, Lee ES, Kenworthy CA, et al. Southeast and East Asian American medical students' perceptions of careers in academic medicine. J Career Develop 2017;46(3):235-250.

- Yi SS, Kwon SC, Suss R, et al. The mutually reinforcing cycle of poor data quality and racialized stereotypes that shapes Asian American health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2022;41(2):296-303.

References

- Martin SS, Aday AW, Allen NB, et al. 2025 heart disease and stroke statistics: A report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2025;151(8):e41-e660.

- Budiman A, Ruiz NG. Asian Americans are the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in the U.S. Accessed April 4, 2025. Available here.

- Shah NS, Xi K, Kapphahn KI, et al. Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease mortality in Asian American subgroups. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2022;15(5):e008651.

- Karter AJ, Schillinger D, Adams AS, et al. Elevated rates of diabetes in Pacific Islanders and Asian subgroups: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Diabetes Care 2013;36(3):574-9.

- Sevillano L, Bacong AM, Maglalang DD. Explaining the variance in cardiovascular health indicators among asian Americans: A comparison of demographic, socioeconomic, and ethnicity. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2025 March 3;doi:10.1007/s40615-025-02341-9

- Shah NS, Luncheon C, Kandula NR, et al. Heterogeneity in obesity prevalence among Asian American ddults. Ann Intern Med 2022;175(11):1493-1500.

- Kianoush S, Al Rifai M, Merchant AT, et al. Heterogeneity in the prevalence of premature hypertension among Asian American populations compared with white individuals: A national health interview survey study. Int J Cardiol Cardiovasc Risk Prev 2022;14:200147.

- Nguyen AB. Disaggregating Asian American and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (AANHOPI) adult tobacco use: Findings from wave 1 of the population assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, 2013-2014. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2019;6(2):356-363.

- Lim A, Elias S, Benjasirisan C, et al. Heterogeneity in the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors by ethnicity and birthplace Among Asian subgroups: Evidence from the 2010 to 2018 National Health Interview Survey. J Am Heart Assoc 2024;13(5):e031886.

- Nadarajah S, Akiba R, Maricar I, et al. Association between sleep duration and cardiovascular disease among Asian Americans. J Am Heart Assoc 2025;14(1):e034587.

- Nguyen KT, Li J, Peng AW, et al. Temporal trends in cardiovascular disease prevalence among Asian American subgroups. J Am Heart Assoc 2024;13(8):e031444.

- Khan SS, Coresh J, Pencina MJ, et al. Novel prediction equations for absolute risk assessment of total cardiovascular disease incorporating cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023;148(24):1982-2004.

- Yi SS, Kwon SC, Suss R, et al. The mutually reinforcing cycle of poor data quality and racialized stereotypes that shapes Asian American Health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2022;41(2):296-303.

Keywords: Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications, Asian Americans, Race and Ethnicity, Heart Diseases, Risk Factors