Anti-Racism: Best Practices For Systems, Departments and Individuals

During ACC.21, Nosheen Reza, MD, FACC, and Toniya Singh, MBBS, FACC, co-hosted a session titled, "Cultivating an Anti-Racist Culture in Cardiovascular Medicine." This session featured fantastic speakers who raised important questions and featured best practices for promoting an anti-racist culture in cardiology. I was particularly struck by the dedication and increasing investment in the past year that has led to opportunities for change at the personal, departmental and institutional level. Three main themes emerged that deserve more attention and space than what I can provide in this editorial, but I hope that this will spark conversations with your co-fellows, attending physicians and your leadership.

1. Start Early

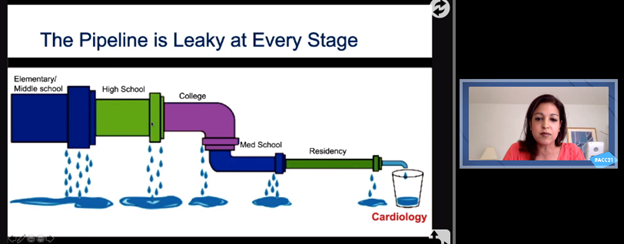

Doreen Defaria Yeh’s adaptation of the “leaky pipeline” diagram starting as early as elementary school that is contributing to low representation of underrepresented in medicine in medicine and cardiology. Click the image above for a larger view.

Doreen Defaria Yeh’s adaptation of the “leaky pipeline” diagram starting as early as elementary school that is contributing to low representation of underrepresented in medicine in medicine and cardiology. Click the image above for a larger view.

It is an old adage – that if we want recruitment of diverse faculty we must start recruiting early – but how early is early? Doreen Defaria Yeh, MD, FACC, presented an adaptation of the "leaky pipeline" diagram that leads to loss of diversity in medicine starting not from residency, not from medical school, but all the way at the elementary and middle school level. She highlighted the initiatives around the country to promote interest early on – the "She Looks Like a Cardiologist" initiative by Katie Berlacher, MD, FACC, in inspiring high school students and the "Kindergarten-to-Med school pipeline" by Quinn Capers, IV, MD, FACC, in increasing retention of underrepresented minorities in the pipeline. While the larger issue of education inequity is an important challenge to overcome on a state/federal level, it is inspiring to hear such community outreach start small with a few dedicated mentors inspiring diverse mentees.

2. Prioritize, Invest and Measure

The systemic changes that Robert Harrington, MD, MACC, shared from Stanford laid out an impressive model on how institutions can start to make tangible changes to improve diversity and inclusion. He shared some innovative ideas to prioritize, invest and measure outcomes. Prioritization included efforts such as use of social media to provide visibility (e.g., #BHM which garnered more than sixty thousand impressions this past February) and formalized introduction of diversity and inclusion efforts for onboarding of residents and fellows. Prioritization was followed by concrete investments – an impressive budget increase from a quarter million dollars to almost 1.3 million dollars in 2021. Investments were allocated to not only fund various projects but attract the personnel – such as the 20% salary coverage for members of the faculty search committee "LENS" (Leading to Equitably Navigate Searches). Grants and awards were created to promote the work of investigators devoted to reducing racial and socioeconomic disparities. The various, well-funded initiatives were followed by concrete outcomes measures. They included publication of the percentage of fellows and professors of different levels who identify as underrepresented minorities in medicine, as well as publication of salaries to assess and discuss gaps across genders and races. I am grateful to see such models that couple dedication with real financial investments and measures that can monitor real progress.

3. Changes to Your Day-to-Day

The speakers shared several practices to promote anti-racist culture in our day-to-day practices. Brittany Smith, PharmD, emphasized the positive impact in team dynamics and patient care that can come from addressing health care team members by appropriate titles. Yeh shared the recent change at Massachusetts General Hospital which requires lecturers to dedicate two slides to racial and socioeconomic disparities on the particular topic. She also noted some concrete ways for interviewers and selection committees to overcome our unconscious biases – such as standardization of questions and redefining "best" applicant beyond the "gut feeling" to include personal characteristics that would bring new and different perspectives to the community.

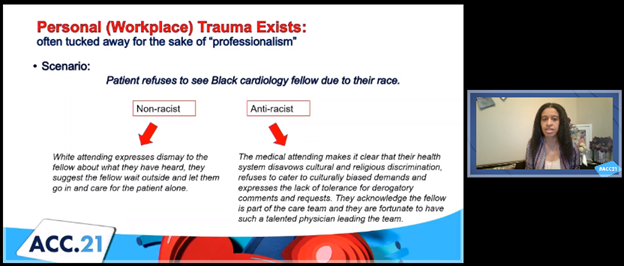

Rachel Bond’s example scenario of racism in health care and the non-racist response vs. anti-racist response. Click the image above for a larger view.

Rachel Bond’s example scenario of racism in health care and the non-racist response vs. anti-racist response. Click the image above for a larger view.

What struck me most about this engagement session was the particular attention paid to the changes we as individuals can make on a day-to-day basis to become anti-racist. Rachel Bond, MD, FACC, highlighted a concrete example of microaggression and bias that lead to personal trauma experienced at the workplace. The example was of a patient who refused to see a black cardiology fellow due to their race. The common response is a private discussion with the fellow and resuming the appointment with the fellow waiting outside the door. Such response, even if not actively endorsing the patient's preferences, is a "non-racist" response which can be defined as an expression of neutrality. The anti-racist in this situation, Bond explained, would disavow such discrimination and to nonetheless include the fellow as part of the care team. We can recognize the discomfort that can stem from the anti-racist response; however, that discomfort should not be misconstrued as "unprofessional" or somehow less than ideal. Bond teaches us that this discomfort is one we must learn to be comfortable.

This example raised the question for me of how we define "professionalism" in our medical community. Rather than avoiding the conversation about racism in situations as mentioned above – which all too often occurs for the sake of "professionalism" or to avoid confrontation – perhaps these are opportunities for us to shape our culture in health care. In addition to the traditional notions of respect, working collaboratively, attending to responsibilities, acting with integrity, let us consider adopting anti-racism explicitly to define professionalism in our medical community and in our day-to-day lives.

ACC Members, discuss

this on Member Hub.

This content was developed independently from the content developed for ACC.org. This content was not reviewed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) for medical accuracy and the content is provided on an "as is" basis. Inclusion on ACC.org does not constitute a guarantee or endorsement by the ACC and ACC makes no warranty that the content is accurate, complete or error-free. The content is not a substitute for personalized medical advice and is not intended to be used as the sole basis for making individualized medical or health-related decisions. Statements or opinions expressed in this content reflect the views of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of ACC.