Fostering the Next Generation of Physician-Scientists in Developing Countries

Research has reshaped medical practice, transitioning it from a primarily experience-driven approach to an evidence-based profession. This evidential foundation is the bedrock for widely adopted practice guidelines, impacting policymakers, clinicians and most importantly, patients. Nevertheless, it is crucial to recognize that most research output originates from high-income countries.1 The research disparity among low-income nations presents multifaceted challenges, including a dearth of insights into pathophysiology, risk factors, treatment outcomes and patterns in these populations with their own unique genetic, cultural and socioeconomic makeup.

The issues of limited medical research output and cultivation of physician-scientists in developing nations are deeply rooted in several underlying factors: encompassing funding constraints, the emigration of skilled researchers to developed countries and the absence of research infrastructure. Recent data from the World Bank highlights that most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa allocate less than 0.1% of their gross domestic product to research and development.2 It is essential to acknowledge that while migration patterns may reduce the number of skilled researchers in developing countries, potentially weakening the experience required for sustained research capacity, those researchers trained in developed countries can play a pivotal role in building and nurturing such capacities more effectively in developing nations.

Perhaps the most important contributing factor behind the lack of research output from developing countries is an almost uniform lack of structured, mentor-guided research training for medical students and junior physicians. Although some medical schools incorporate research modules, these often lack practical depth and emphasize theoretical concepts. Despite investments in research by non-profit and governmental organizations, practical, cost-effective and sustained integration of research education into curricula is lacking. A crucial shift is needed to address this; from treating research as supplementary to seamlessly integrating it into medical training. The current compartmentalization diminishes the impact of research education, underscoring the necessity for a holistic strategy recognizing the interdependence of clinical and research skills.

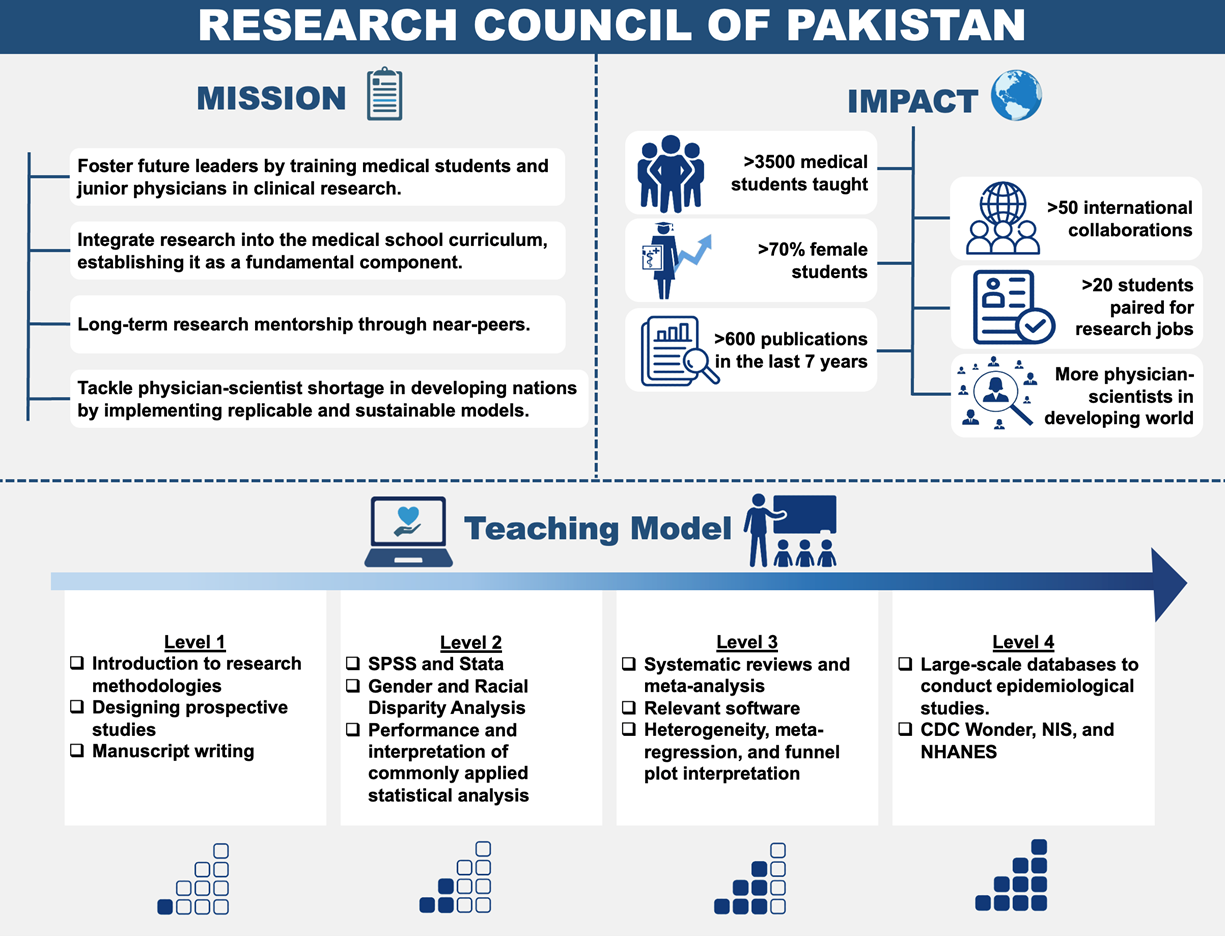

In pursuit of this objective, the Research Council of Pakistan (RCOP) was established in Pakistan – a low-income country with the fifth-largest population in the world. Almost 13,000 medical students graduate as doctors yearly in Pakistan, but medical research output has historically been meager.3 The mission of RCOP is to foster future leaders in academic medicine by providing comprehensive training to medical students and early-career physicians in clinical research (Figure). RCOP has been successful in fostering a research culture across medical schools in Pakistan – with >3,500 students taught over eight years and over 400 articles published to date by students. Moreover, >70% of students are female, and a third are from rural areas within Pakistan. The approach used by RCOP is reproducible and can potentially create innumerable scientists if applied widely across low-income countries.

RCOP's research workshops are designed for medical students with limited or no prior research experience. Its teaching model presented research as a practical scientific tool rather than an abstract concept. The interactive and collegial classroom environment optimizes engagement, trust and team building, fostering ongoing collaboration. Shifting classes online during the pandemic through Zoom significantly expanded participation, enabling students nationwide to join. These measures increased publication rates across all regions, socioeconomic statuses, specialties and genders among medical students.

RCOP employs 'near-peer' instructors, who are only slightly ahead in the career stage but have significant research experience. They, in turn, receive mentorship from senior researchers, often established researchers in North America or Europe. Near-peer training proved most effective with participants motivated by achievable career milestones. Combining this with long-term mentorship yielded the best results. Over seven years, 600 publications emerged from providing long-term group mentorships to previously hesitant students, creating a sustainable mentoring model.

Cardiovascular diseases result in significant morbidity and mortality in Pakistan, exerting an unsustainable economic toll.4-5 Research workshops sparked local interest, fostering international collaborations with cardiologists and yielding publications in high-impact journals. Students exposed to these workshops pursued post-doctoral fellowships and advanced graduate degrees in the U.S. This model, replicable in diverse income settings, leverages targeted and accessible learning resources.

The surge in physician-scientists in the developing world will foster global collaboration, addressing scientific challenges with an emphasis on equitable partnerships. This approach extends to widening the conduct of research, ensuring a timely, cost-effective and practical generation of evidence. Models such as RCOP promise to alleviate the shortage of physician-scientists in developing countries.

References:

- Publication Output by Country, Region, or Economy and Scientific Field. https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb20214/publication-output-by-country-region-or-economy-and-scientific-field. Accessed on Nov. 27, 2023.

- Research and development expenditure (% of GDP) - Sub-Saharan Africa. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/GB.XPD.RSDV.GD.ZS?locations=ZG Accessed on Nov. 27, 2023.

- Research Council of Pakistan. www.rcop.pk. Accessed on Nov. 27, 2023.

- Khan MS, Fatima K, Butler J. Creation of next generation of diverse cardiovascular physician-scientists from developing countries: insights from Research Council of Pakistan. Eur Heart J. 2023 Aug 12:ehad493. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad493. Epub ahead of print.

- Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Dec 22;76(25):2982-3021.

This article was authored by Mohammad Shahzeb Khan, MD, a PGY6 Cardiology Fellow at Duke University School of Medicine.

Twitter: @ShahzebKhanMD

This content was developed independently from the content developed for ACC.org. This content was not reviewed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) for medical accuracy and the content is provided on an "as is" basis. Inclusion on ACC.org does not constitute a guarantee or endorsement by the ACC and ACC makes no warranty that the content is accurate, complete or error-free. The content is not a substitute for personalized medical advice and is not intended to be used as the sole basis for making individualized medical or health-related decisions. Statements or opinions expressed in this content reflect the views of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of ACC.