Feature | Alaska Native Heart Health and Delivery of CV Care

Alaska has a total area that exceeds 660,000 square miles, including more than 94,000 square miles of water, making it the largest state by area in the U.S. To understand the scale of this, Alaska is one-fifth the size of the lower 48, and bigger than Texas, California and Montana combined.

The state also has 228 federally-recognized indigenous tribes. Alaska Natives and American Indians make up about 24% of the state's population, with about one-third living in rural or remote locations.

With the combined challenges of distance and weather, it's an unusual place to practice medicine. Because of the warmth and graciousness of the Alaskan Native people, it is equally an unusually rewarding place to practice medicine.

This month, Cardiology spoke with two clinicians with a combined 30+ years of experience practicing cardiology in Alaska to understand the health challenges facing Alaska Natives and the challenges they face in delivering cardiovascular care.

A Model of Successful Self-Determination

Health services for Alaskan Natives basically run like a gigantic health maintenance organization, governed and managed by the native Tribes themselves. Before 1998, health services were provided by the Indian Health Service (IHS), an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services, tasked with providing federal health care to American Indians and Alaska Natives.

In 1998, the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC), a nonprofit Tribal health organization, signed a contract transferring statewide services from IHS to themselves. This enabled them to receive the IHS annual budget allotment, supplemented by billings to Medicare, Medicaid and private insurances.

ANTHC co-manages a medical center dedicated to Alaska Native health and other tribal health facilities of the Alaska Tribal Health System (ATHS). The Consortium is Alaska's second-largest health employer with more than 3,000 employees offering an array of health services to people around the nation's largest state.

One Medical Center, Massive Catchment Area

The Alaska Native Medical Center (ANMC) in Anchorage is a unique place. The award-winning medical center serves 180,000 Alaska Natives and American Indians and includes a 173-bed hospital, a full range of medical specialties, primary care services and labs. The center is also home to more than 1,000 pieces of Alaska Native art, many of which are of museum quality.

Currently, the ANMC cardiology clinic is staffed by four full-time and two part-time cardiologists and three cardiology advanced nurse practitioners. A catheterization laboratory was opened in 2015, which is shared with the interventional radiology team.

"We take care of NSTEMI in our cath lab, but we send the STEMIs to another hospital in Anchorage that has a full-time interventionalist. As you can imagine, the 90-minute door-to-balloon time is very difficult in Alaska. We use more thrombolytics than other places," says Joseph H. Park, DO, the chief of cardiology at ANMC.

To serve the needs of their patients living across a vast and remote area, the ANMC cardiology section offers 28 field clinics across Alaska throughout the year. In-person visits are supplemented with telemedicine.

Telehealth came to Alaska long before the current pandemic brought it to the rest of the country. "It's all about logistics up here and figuring out how to deliver care to people in remote locations. Telehealth has been a tremendous asset to us," says Park.

Cardiologist Matthew J. Schnellbaecher, MD, FACC, the former chief of cardiology at ANMC, now works there part time. He estimates that in the early days, when it was just him and a second cardiologist covering the entire state, he'd spend about 75 days a year on the road seeing patients in remote villages and towns.

"My colleague at that time and I split the state. We really got to know all the people with heart disease in our area," says Schnellbaecher. Most of the time there were commercial flights available, but occasionally their trips required a "puddle jumper" and some type of rugged ground transportation.

Generally, they'd have a three-day clinic. An echo tech would be with them one day and a device rep from one of the pacemaker companies on another day. "As Alaska Natives, all of the patients have insurance coverage. We're all salaried providers, so we don't have some of the worries that physicians in other places may have. And it's a really neat way to practice cardiology," he adds.

When patients need to be seen at ANMC, a trip to Anchorage is arranged, usually trying to coordinate multiple doctor's visits in one trip.

"It really does work like an HMO in many ways," says Schnellbaecher. "It behooves everyone to direct effort and resources to preventive care, health maintenance and primary care in rural areas. This is better for the overall well-being of patients and for the health system, rather than waiting until a person's health has deteriorated, requiring an expensive medevac into Anchorage."

Community Health Aides

An invaluable part of the ANMC health system is the community health aides who work alongside licensed providers to offer patients increased access to trained care in rural areas. Aides undergo about 15 weeks of basic training before credentialing. "The health aides are one of the linchpins of the health care system in Alaska. We couldn't do what we do without them," says Schnellbaecher. Indeed, the program has been so successful that in 2018, the IHS expanded it to the lower 48 states.

The Community Health Aide Program received formal federal recognition and congressional funding in 1968 and today they function as part of a regional team to assess and provide emergent, acute and chronic medical care in remote Alaskan communities.

The success of the community health aide model, deemed not just clinically effective but also efficient and cost-effective, formed the beginnings of a model of care that has expanded to other areas of health care in the ATHS, including the Dental Health Aide Program and the Behavioral Health Aide Program.

The aides work in remote villages that could have anywhere from 50 to 800 people and everybody knows each other. Often the aides are related to a number of the people they serve, adds Schnellbaecher.

The ATHS works on a hub-and-spoke model to increase access to care in individual communities and subregional clinics using about 550 community health aides dispersed among 170 rural villages. Most specialist cardiology care is provided at the ANMC in Anchorage.

"The job can be stressful," says Schnellbaecher. For example, he explains, when a community health aide in Gambell, a small town on St. Lawrence Island 200 miles from Nome, has a patient with chest pain, a call is made by the aide to the regional hospital in Nome to talk with the doctor who is on radio traffic that day. That doctor reviews the EKG and tells the aide the next steps and contacts ANMC in Anchorage directly if it's necessary.

"You can imagine with the size of this state just how important the community health aides are for providing care. When we go out to small villages to see patients, they are right there helping us. They know the patients, know their family situations and understand the culture, so their work is really critical to what we do," he adds.

The Best Patients and a Wonderful Place to Live

A common theme heard from both Schnellbaecher and Park is a deep affection and appreciation for the patients they serve.

"Our patients really are like family. They'll often come in bringing gifts for us, like fish they caught or a beautiful handmade craft.

They are very generous and loving, and they are the biggest reason I've stayed here," says Park who hails from Orange County, CA.

"We also have wonderful schools here in Anchorage and while the winters are quite cold, the summer is wonderful," he adds. "It's a slower pace of life than what I grew up with in Southern California."

Schnellbaecher adds, "The Alaska Native people are super friendly. I've known some of my patients for 25 years now, and they've become our friends. Often, I'll get to know three generations of a family because there might be a 95-year-old elder being cared for by his or her 14-year-old grandson. There's still that emphasis here on the family unit that you don't see so often anymore."

A life in Alaska wasn't Plan A for either Schnellbaecher or Park. Shortly after he finished his training in New York City, Schnellbaecher was using up some frequent flyer miles and went to Alaska on vacation with his wife in 1995. They decided to stay. Park was living in Michigan and in his third year of fellowship training in 2013 when he decided to do a rotation with Schnellbaecher at ANMC and got hooked too.

"When I first came up here to train and I saw how Matt would see patients – the visits weren't rushed, there was time to catch up and talk about things. It just felt like you were seeing an old friend and I thought that's the way I want to practice medicine," says Park.

"I asked my wife if we could give it a shot for a year, maybe do some fishing and explore nature, and she fell in love with the place too."

Alaska Native Epidemiology

Historically, Alaska Native people have exhibited low overall rates of heart disease mortality compared with the U.S. White population. Indeed, the age-adjusted Alaska Native heart disease mortality rate was consistently about 20% lower than that seen in the U.S. White population from 1981 through 2007, albeit with some important differences seen across ages and disease subtypes.1

"When I first came here, the physicians who'd been here in the 1960s and 1970s told me that injury, trauma or pericarditis were the most common reasons patients presented with chest pain, says Schnellbaecher. Valve problems brought on by rheumatic heart disease were also common then.

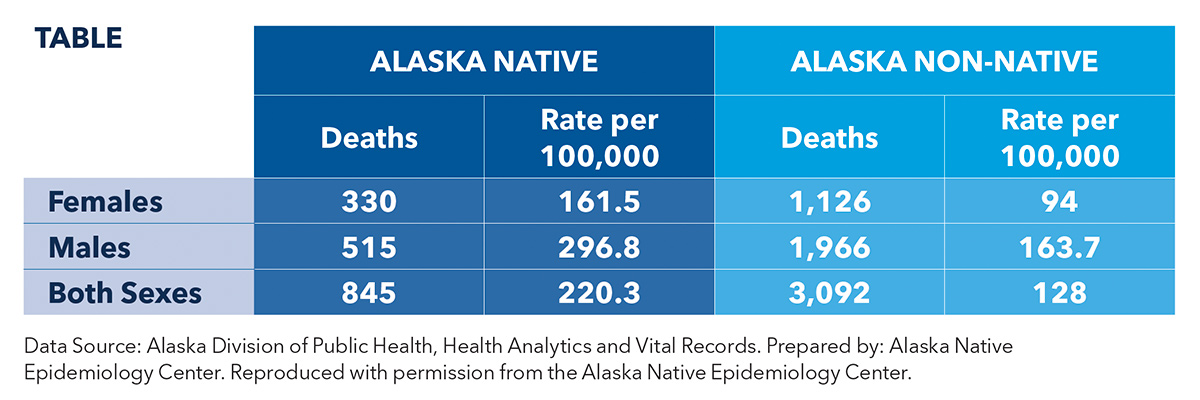

As with other indigenous groups, as Alaska Natives have moved away from their traditional diets and ways of life, things have changed. A report from the Alaska Native Epidemiology Center showed that while there has been a declining trend in heart disease mortality from 1993 to 2017 among Alaska Native people, the rates remain higher compared with non-Native Alaskans. The age-adjusted mortality rate in 2017 was 211.3 vs. 120.2 deaths per 100,000, respectively. The rates by gender are shown in the Table. Of note, substantial variation was seen among different tribes in different regions of the state.

Park notes there is limited comparative outcomes research focused on cardiovascular care delivery in Alaska. One effort that Schnellbaecher has been involved in is the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Healing and Empowering Alaskan Lives Toward Healthy Hearts (HEALTHH) project.2

HEALTHH uses telemedicine to address significant inequities in tobacco use and tobacco-related disease in the Norton Sound Region of Alaska, with the expectation that the intervention can be rolled out to other Alaska Native communities. While overall smoking prevalence in Alaska is about 18%, the rates are much higher among Alaska Natives, where one in two men and one in three women smoke cigarettes. The study aims to identify culturally-tailored, theoretically-driven, efficacious interventions for tobacco use and other cardiovascular disease risk behaviors among Alaska Native people in remote areas.

Of the 299 participants in the study, half were randomized to telemedicine-based counseling for quitting smoking and exercising, and half to telemedicine-based counseling for a heart-healthy Native diet and compliance with medications for hypertension and/or high cholesterol. Outcomes have not been published yet.

References

- Johnston JM, Day GE, Veazie MA, Provost E. Heart disease mortality among Alaska Native people, 1981-2007. Public Health Rep Wash DC 1974. 2011;126:73-83.

- Prochaska JJ, Epperson A, Skan J, et al. The Healing and Empowering Alaskan Lives Toward Healthy-Hearts (HEALTHH) Project: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of an intervention for tobacco use and other cardiovascular risk behaviors for Alaska Native People. Contemp Clin Trials 2018;71:40-46.

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Dyslipidemia, Geriatric Cardiology, Prevention, CHD and Pediatrics and Prevention, CHD and Pediatrics and Quality Improvement, Lipid Metabolism, Nonstatins, Diet, Exercise, Hypertension, Smoking

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Adolescent, Aged, Aged, 80 and over, Alaska, Alaskan Natives, Ambulatory Care Facilities, American Natives, Awards and Prizes, Cardiologists, Cardiology, Cardiovascular Diseases, Chest Pain, Cholesterol, Cities, Community Health Workers, Cost-Benefit Analysis, Counseling, Credentialing, Delivery of Health Care, Diet, Exercise, Fellowships and Scholarships, Friends, Gift Giving, Health Maintenance Organizations, Health Services, Health Services Accessibility, Heart Diseases, Hospitals, Hypertension, Love, Maintenance, Medicaid, Medicare, Michigan, Montana, Motivation, Museums, New York City, Nurse Practitioners, Outcome Assessment, Health Care, Pacemaker, Artificial, Pandemics, Patient Care, Physicians, Population Groups, Power, Psychological, Prevalence, Primary Health Care, Public Health, Recreation, Rheumatic Heart Disease, Rotation, Smoke, Smoking, Smoking Cessation, Spouses, Telemedicine, Texas, Tobacco, Tobacco Products, Tobacco Use, United States Indian Health Service, Water, Weather

< Back to Listings