Focus on Heart Failure | Existing Disparities and Improving Access to Advanced Heart Failure Care Among Underrepresented Populations

Advanced heart failure (HF) is one of those conditions that you "know it when you see it." It is estimated that approximately 5% of the 6.2 million Americans with HF may develop advanced disease.1 Fortunately, with the evolution of novel medical therapies as well as left ventricular assist device (LVAD) technology and advances in heart transplantation, the trajectory of the illness can be transformed.

According to one analysis of treatment effects with angiotensin-receptor neprilysin inhibitors, beta-blockers and mineralocorticoid antagonists, combined therapies were estimated to afford up to six additional years of survival (for a 55-year-old).2 With the most recent LVAD, HeartMate 3, two-year survival following implantation is approximately 80%, which is comparable to heart transplantation.3

We have excellent tools in our arsenal. The key is to ensure the patients who need them the most can benefit from them.

Identifying Those in Need

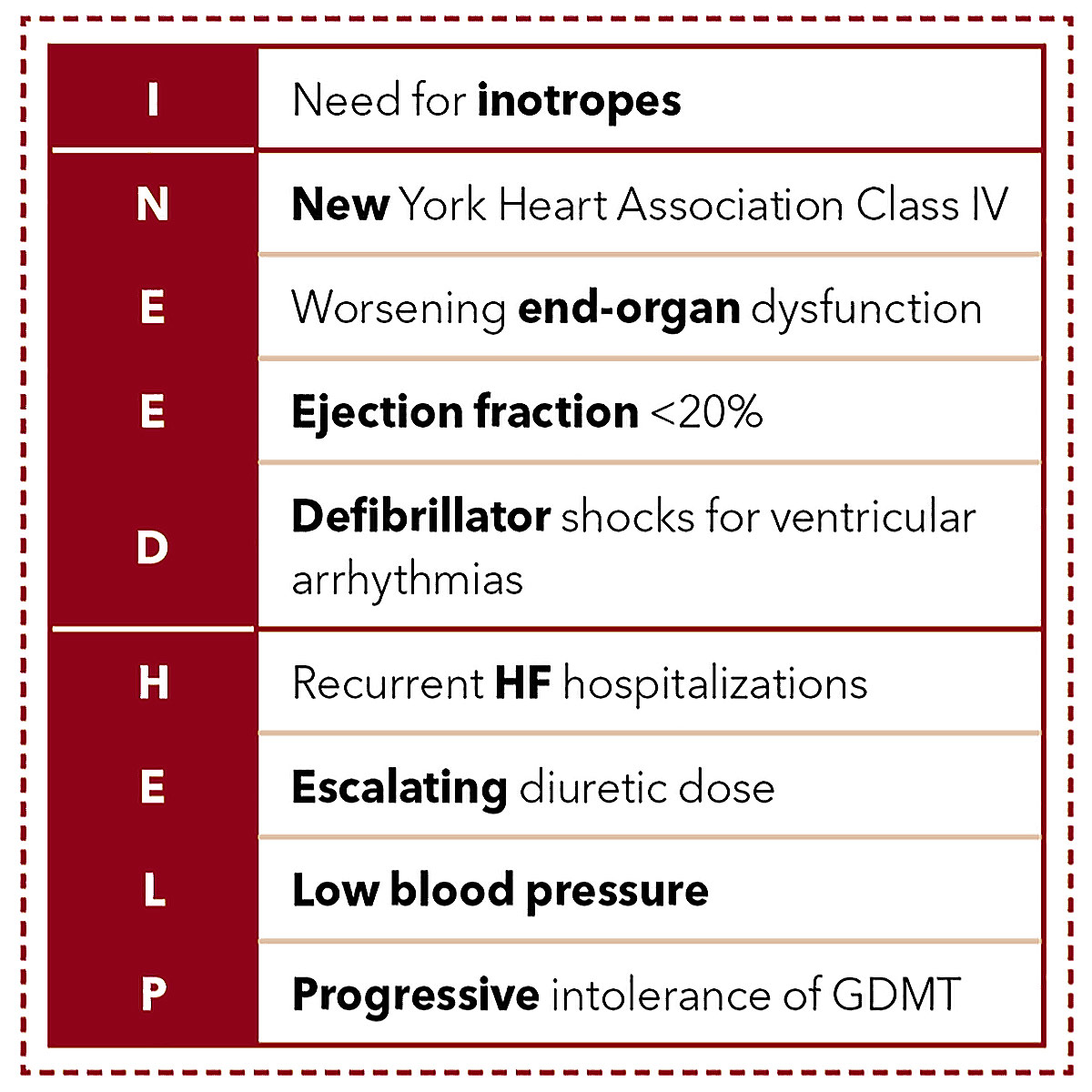

One common mnemonic that is used to identify patients with symptoms and signs of advanced HF is I NEED HELP (Table).

These "warning signs" should prompt referral to an advanced heart failure and transplant cardiologist (AHFTC). As specialists, AHFTC physicians aim to ensure that medical and device therapies are being used when able in the right patient. They can also discern whether the patient is likely to benefit from an LVAD or heart transplantation. Moreover, they can guide expectations from the patient and family regarding prognosis and end of life.

Unfortunately, there are many patients who may not have access to AHFTCs or who may be referred too late. The impact of social determinants of health and implicit bias on referrals for advanced HF therapies was highlighted in a recent Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association with a writing group led by Alanna A. Morris, MD, MSc, FACC.1 The populations less likely to be referred include women, underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, and residents in rural areas.

Black adults have the highest rates of HF hospitalization, readmission and five-year mortality after diagnosis.4,5 Increasingly concerning is a rise in premature heart-failure related deaths in young and middle-aged Black men.6 Despite this, Black adults are less likely to receive cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), less likely to be referred to cardiac rehab, and less likely to receive care by a cardiologist (let alone a heart failure specialist) when admitted to an intensive care unit for HF.4 Additionally, the rate of heart transplantation in many areas of the country is less relative to the HF mortality for Black patients in those areas.7

Similarly, women are less likely to receive an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) or CRT despite increased benefit, less likely to be referred to cardiac rehab, and are more likely to report anxiety or depression with less improvement in quality of life.8

When patients are referred "too late," many may have developed irreversible extracardiac manifestations of their HF including liver or renal dysfunction that may preclude them from receiving advanced therapies. This may close doors to certain options that may have been available if they were evaluated earlier. For example, women are more likely to be in cardiogenic shock at the time of LVAD implantation compared with men.9

We See Them Every Day – In Our Hospitals

The populations less likely to be referred include women, underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, and residents in rural areas. Black adults have the highest rates of HF hospitalization, readmission and five-year mortality after diagnosis. Increasingly concerning is a rise in premature heart-failure related deaths in young and middle-aged Black men.

Sometimes these patients are even in our own hospitals, but still not receiving the care they need. In one eye-opening study from Brigham and Women's Hospital, the authors evaluated all patients admitted with HF over a nine-year period.10 Black and Latinx patients were significantly less likely to be admitted to a cardiology service compared with White patients. Similarly, women and older adults were less likely to be admitted to cardiology services. Yet, those patients admitted to the cardiology service had fewer readmissions for HF within 30 days.10

Nine HF centers performed an analysis where they looked at patients who had been referred for evaluation for LVAD or heart transplantation.11 They reviewed 515 referrals of whom nearly three-fourths were men. Approximately 30% of patients were Black and 9% were Hispanic. About half of the referrals stemmed from other HF cardiologists. Patients were referred as a result of worsening HF, need for continuous inotropes, cardiogenic shock or recent hospitalization. Notably, almost 60% of evaluations were performed in the inpatient setting highlighting a high level of patient acuity and advanced disease states.

Unfortunately, 56% of patients were declined or deferred for transplant, most commonly because patients were too sick as a result of comorbidities or end-organ dysfunction (45%).11 Only 57% of patients were approved for LVAD therapy; similarly 38% of patients were declined because patients were too sick. These findings highlight the stark reality: we must do better to identify these patients earlier. And as mentioned, who are those who will be referred late (or not at all)? Women, Black patients and Hispanic patients.

This is not to say that early referral to a HF center alone will ensure equity. We know that as HF clinicians, we too are not immune to bias. We must be self-aware and recognize our own preconceived notions. Khadijah Breathett, MD, MS, FACC, conducted a study in which she approached members of the HF community at a conference. Participants were shown one of four identical clinical vignettes.12 The only differences were the patient race and sex. A few themes emerged: women were judged more harshly by their appearance compared with men; the Black man was perceived as the sickest of the four patients; similar social support was deemed adequate for men but not for women with children for whom this was perceived as a liability, particularly for the Black woman.12

Combating Bias

Dr. Melvin Echols Named ACC's Chief Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Officer

The ACC has named Melvin R. Echols, MD, FACC, as its new Chief Diversity, Inclusion (DEI) Officer. He will lead the College's DEI strategy and programs, while also maintaining a portion of his current clinical and research responsibilities at Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta. In his new role, Echols will use his expertise and experiences to work with ACC members, staff, external partners and other stakeholders to identify and implement programmatic goals and develop actionable and sustainable solutions to achieving a more diverse, equitable and inclusive College and cardiovascular profession.

"The discovery of commonalities between people and culture while providing quality cardiovascular care to all is strengthened by diversity, and will ultimately improve health equity in our society," Echols says. "Everyone has a part to play in this mission and should feel included in helping to make our society and the world better than yesterday."

Improving access to HF care for underrepresented populations and allocation of advanced therapies requires a multipronged approach.

By partnering with community clinics with vulnerable patient populations, we can help educate providers including primary care physicians and general cardiologists about signs of worsening HF and the timing of referral. Additionally, community resources such as patient navigators and expanded support services can help improve health literacy and overcome barriers such as transportation and ease navigating a complex health care system.

Artificial intelligence may provide opportunities to predict HF phenotypes as well as identify patients who are being undertreated with guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) and those who are at high risk for adverse outcomes.13 Yet, it is important to be aware of the potential for bias given that these models are only as reliable as the data from which they are built; there is the potential for algorithmic bias and social bias.13

It is imperative to improve the diversity of our care teams. This includes physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, social workers, support staff, and more. Having a provider who "looks like you" can provide tremendous comfort and reassurance to a patient. Not only are there shared cultural beliefs and in some cases a shared language, but diversity also improves the quality of care delivered.

By enrolling diverse populations in clinical trials, we can improve the evidence base of various therapies in underrepresented populations.14 This will not only ensure that we understand if there is differential efficacy and safety signals in all of our patients with HF, but also help to engage communities in the research enterprise. The current underrepresentation of all populations in clinical trials is likely a result of limited access to subspecialty clinical care for many, thus requiring concerted efforts be made to partner with communities, deliberately selecting sites for research studies in areas of need, as well as designing smarter and more accessible clinical trials for our patients.

Everyday Actions Can Count

We have evidence that the use of CRT, cardiac rehab, specialist care and heart transplantation is lower in Black adults who would benefit, and the use of ICDs, CRT and cardiac rehab is lower in women with advanced HF.

Far too often – even in leading institutions – patients who are Black, Hispanic, female or older with advanced HF are overlooked and not referred for care by a cardiologist and especially an advanced heart failure specialist. Moreover, too many patients with advanced HF who would benefit from treatment simply are not getting them. We have evidence that the use of CRT, cardiac rehab, specialist care and heart transplantation is lower in Black adults who would benefit, and the use of ICDs, CRT and cardiac rehab is lower in women with advanced HF. This undertreatment of underrepresented populations contributes to the increasing burden of heart failure for individual patients and the health care system at large that we all read about regularly.

To combat these inequities and structural racism, there must be change at the personal, institutional and systems levels. Hospital systems should look inwards at the patients they are serving to determine if their patients are getting appropriate care. Partnering with communities for outreach clinics and education regarding signs of advanced HF can help improve referral patterns. By emphasizing the need for affordability and insurance coverage for HF medications, we can minimize the financial burden of HF for those of low socioeconomic status. Each of us can make time to learn and recognize our implicit biases and how this may affect the care we deliver to our patients.

These collective changes can aim to bring us one step closer to health equity. Our patients are counting on us.

Ersilia M. DeFilippis, MD, is an advanced heart failure and transplant cardiologist and assistant professor of medicine at Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) in New York. Reach out to her via Twitter @ersied727.

References

- Morris AA, Khazanie P, Drazner MH, on behalf of the American Heart Association Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; and Council on Hypertension. Guidance for timely and appropriate referral of patients with advanced heart failure: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021;144:e238-e250.

- Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Jhund PS, et al. Estimating lifetime benefits of comprehensive disease-modifying pharmacological therapies in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: A comparative analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2020;396:121-28.

- Varshney AS, DeFilippis EM, Cowger JA, et al. Trends and outcomes of left ventricular assist device therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:1092-1107.

- Breathett K, Liu WG, Allen LA, et al. African Americans are less likely to receive care by a cardiologist during an intensive care unit admission for heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2018;6:413-20.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, et al. Racial Differences in Incident Heart Failure among Young Adults. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1179-90.

- Nayak A, Hicks AJ, Morris AA. Understanding the complexity of heart failure risk and treatment in black patients. Circulation: Heart Failure 2020;13:e007264.

- Breathett K, Knapp SM, Carnes M, et al. Imbalance in heart transplant to heart failure mortality ratio among African American, Hispanic, and White Patients. Circulation 2021;143:2412-14.

- Dewan P, Rørth R, Jhund PS, et al. Differential impact of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction on men and women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:29-40.

- Blumer V, Mendirichaga R, Hernandez GA, et al. Sex-Specific outcome disparities in patients receiving continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices: A systematic review and meta-analysis. ASAIO J 2018;64:440-9.

- Eberly LA, Richterman A, Beckett AG, et al. Identification of racial inequities in access to specialized inpatient heart failure care at an academic medical center. Circulation: Heart Failure 2019;12:e006214.

- Herr JJ, Ravichandran A, Sheikh FH, et al. Practices of Referring patients to advanced heart failure centers. J Cardiac Fail 2021;27:1251-9.

- Breathett K, Yee E, Pool N, et al. Association of gender and race with allocation of advanced heart failure therapies. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2011044.

- Johnson AE, Brewer LC, Echols MR, et al. Utilizing artificial intelligence to enhance health equity among patients with heart failure. Heart Fail Clin 2022;18:259-73.

- DeFilippis EM, Echols M, Adamson PB, et al. Improving enrollment of underrepresented racial and ethnic populations in heart failure trials: A call to action from the Heart Failure Collaboratory. JAMA Cardiol 2022;7:540-8.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiac Surgery, Cardiovascular Care Team, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Prevention, Implantable Devices, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and Heart Failure, Acute Heart Failure, Heart Failure and Cardiac Biomarkers, Heart Transplant, Mechanical Circulatory Support, Stress

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists, Neprilysin, Patient Readmission, Quality of Life, Heart-Assist Devices, Health Literacy, Depression, Depression, Motivation, American Heart Association, Artificial Intelligence, Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy, Defibrillators, Implantable, Ethnic Groups, Financial Stress, Health Equity, Inpatients, Multiple Organ Failure, Patient Navigation, Physicians, Primary Care, Shock, Cardiogenic, Social Determinants of Health, Social Workers, Heart Transplantation, Heart Failure, Prognosis, Anxiety, Referral and Consultation, Intensive Care Units, Social Class, Kidney Diseases, Insurance Coverage, Quality of Health Care, Patient Acuity, Costs and Cost Analysis, Social Support, Social Support, Angiotensins, Patient Care Team, Phenotype, Hispanic Americans, Hospitals, Liver, Technology

< Back to Listings