COCATS, Boards and the ACGME: A History of Standards in Cardiology Fellowship Training

Noted cardiologist and medical educator J. Willis Hurst, MD, once commented that for motivated trainees, achievement might be best supported by open-ended fellowship programs with minimal structure. "But," he lamented, "because we do not live in Camelot, where all is perfect, we must set basic standards."

As an applicant, I was reminded frequently of the imperative "COCATS numbers" and encountered the concept of skill-specific board exams. Who is making the rules that drive our training experience and career prospects? For those sharing my perplexity, I offer a historical perspective and explanation of the guidelines shaping cardiology training.

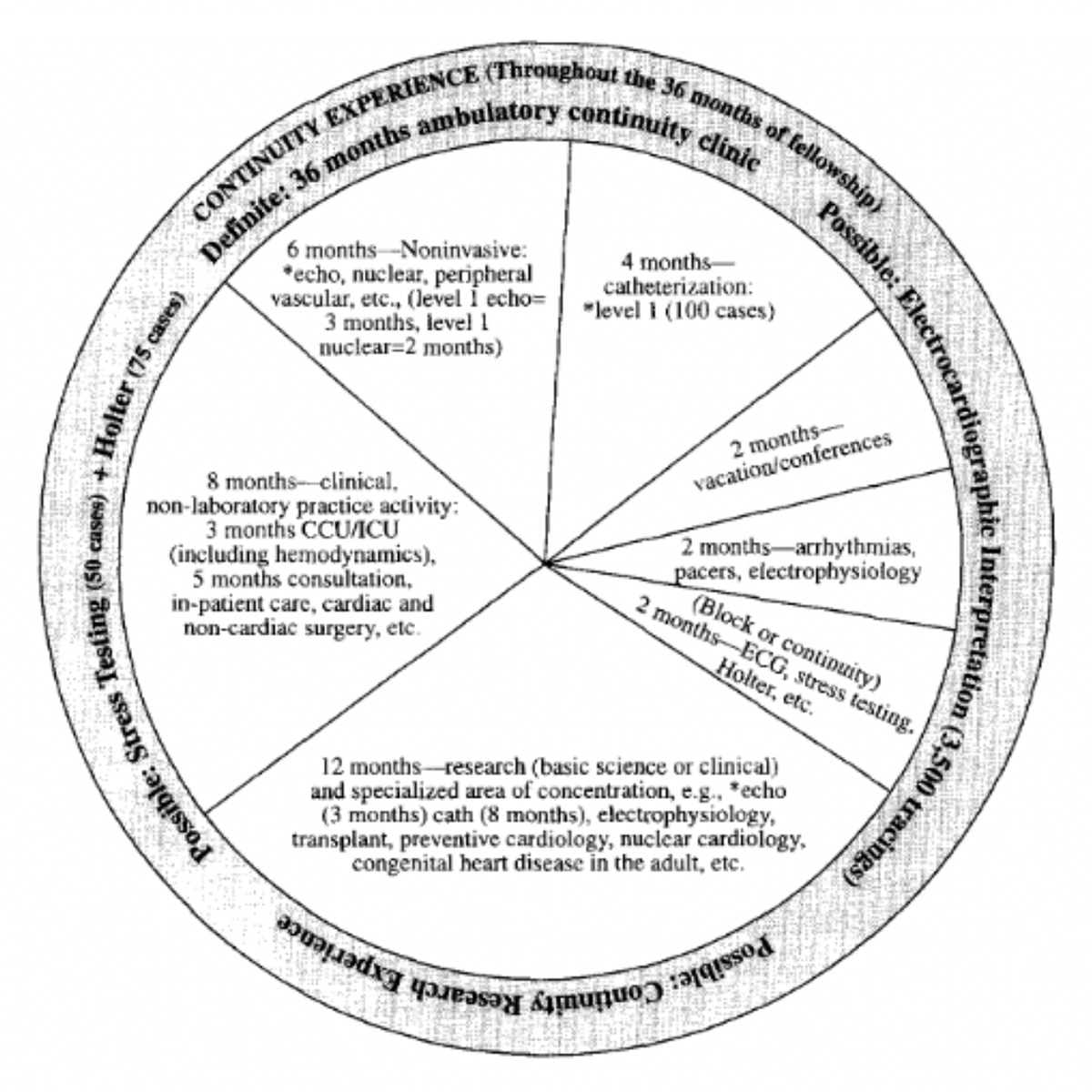

COCATS is one component of a professional aim to standardize cardiology training. The term entered our lexicon when Guidelines for Training in Adult Cardiovascular Medicine was released from the 1994 ACC Core Cardiology Training Symposium (COCATS). The authors reflected on the need to revise training expectations due to progressively sophisticated diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and a population with increasing disease complexity.

This document was an update of the Adult Cardiology Training guidelines arising from the 17th Bethesda Conference in 1985, contemporaneous with the lengthening of standard cardiology fellowship from two years to three. The original framework had eight sections, each written by an expert subcommittee.

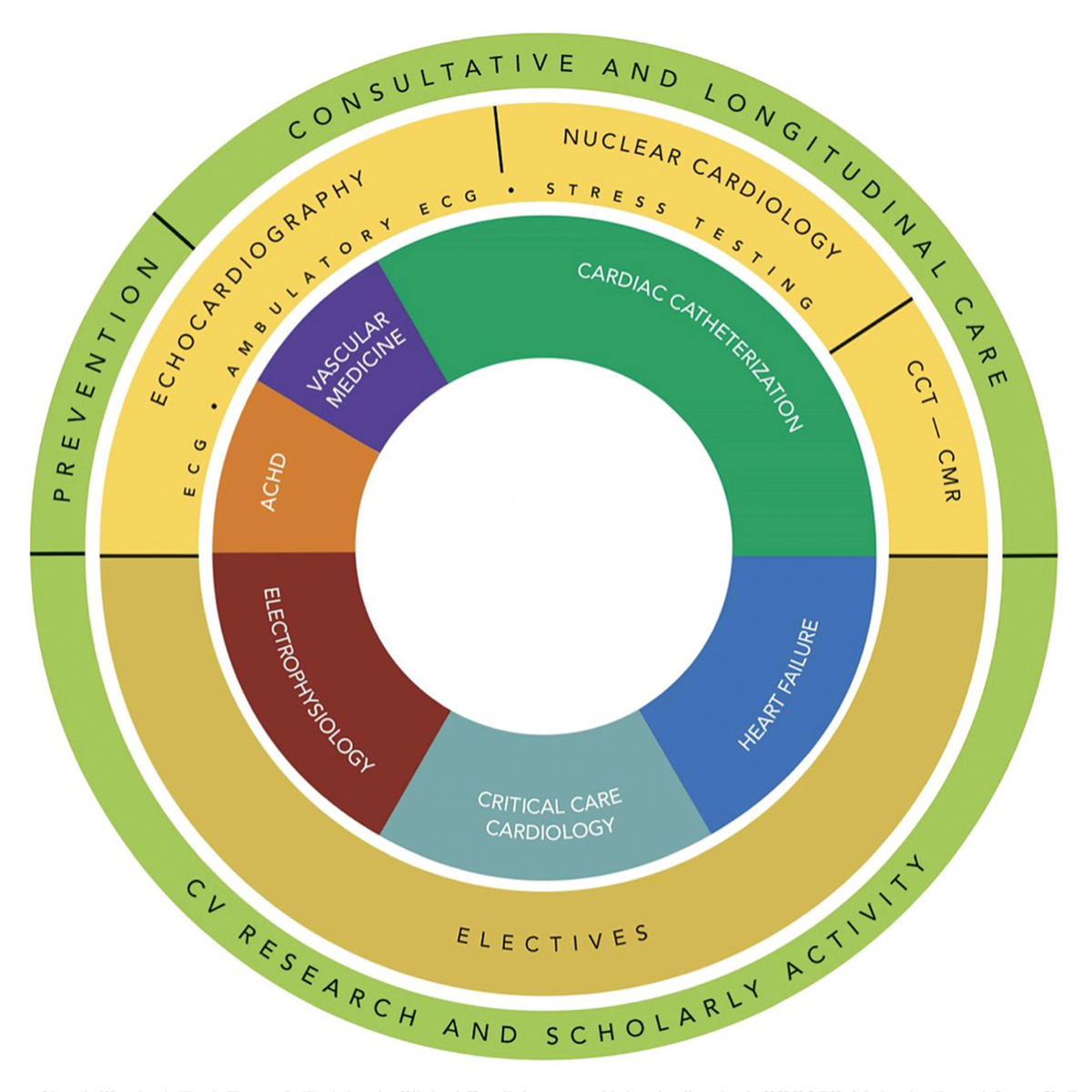

After COCATS 1994 and updates in 2002, 2006 and 2008, the current COCATS 4 framework was released in 2015 with 15 expert task force sections. COCATS 4 was approved by the American Heart Association and subjected to public comment prior to final published version.

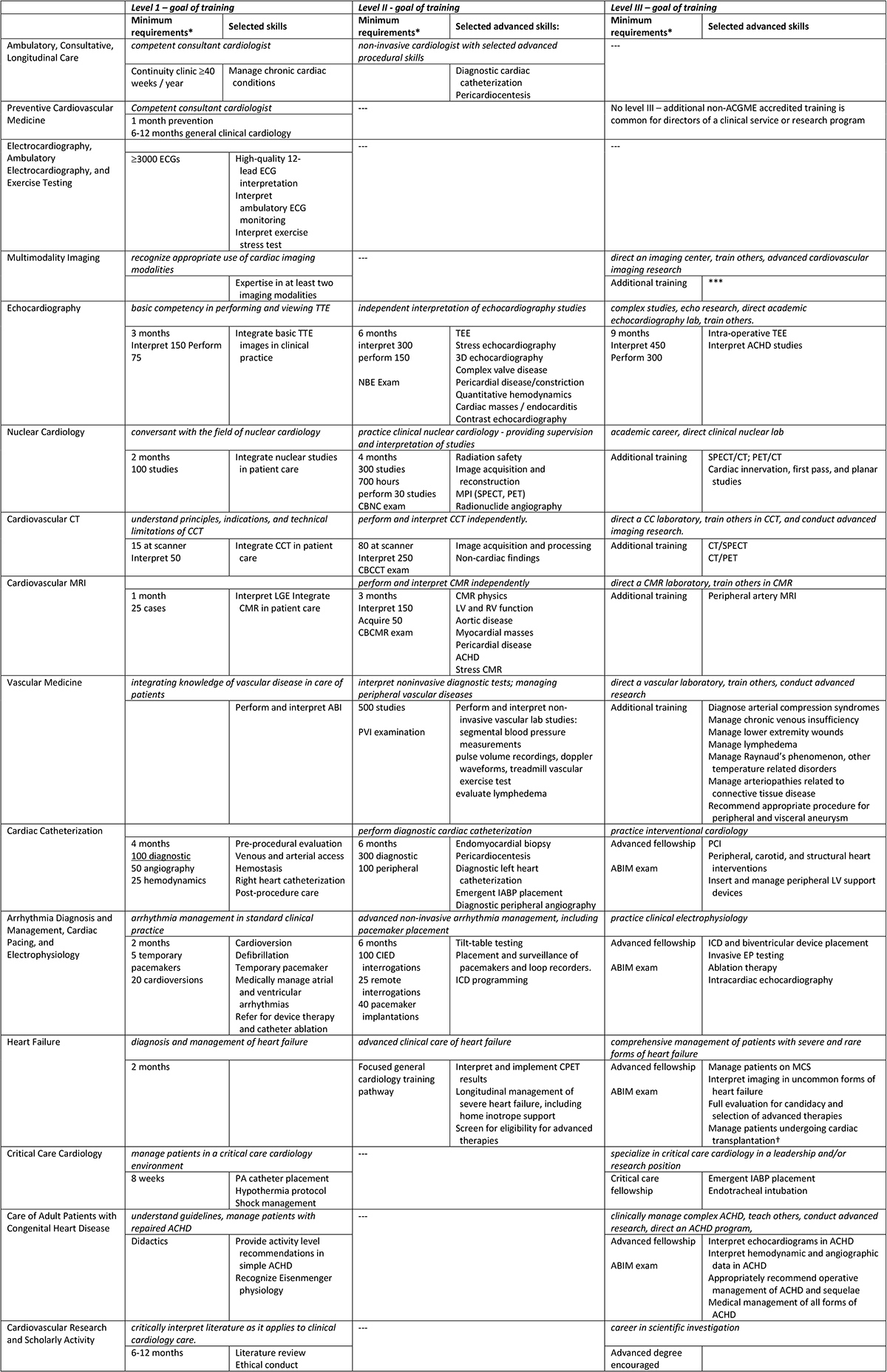

COCATS can best be understood as recommendations from the ACC regarding fellowship training. It provides expected milestones within each section categorized into six core competencies of post-graduate education recognized by the American College of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME): patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice. Milestones are designated for level I, level II and level III expertise.

Level I is the degree of knowledge and experience expected of every graduating trainee (e.g., incorporating echocardiography into patient care). Level II, a higher degree of mastery, offers distinct career opportunities (e.g., certification to provide formal interpretation of echocardiograms). Level III requires training beyond general cardiology and equips one to perform advanced procedures or clinical care (e.g., direct an echocardiography laboratory).

While some milestones are accompanied by a minimum number of required procedures, each COCATS edition has emphasized that reaching these numbers is not synonymous with demonstrating competency, and should simply serve as a starting point for evaluation.

While fellowship programs rely heavily on COCATS framework to guide training models, the ACGME actually accredits all post-graduate training programs. COCATS and ACGME time and procedure minimums generally correlate, though COCATS is far more detailed. Board certification is facilitated by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), dependent on completion of an ACGME-accredited fellowship and passing the ABIM-sponsored exam.

Independent practice for some realms of general cardiology – echocardiography, nuclear medicine, CT, MRI and vascular medicine – require certification with independent exam sponsors, which generally require Level II experience.

For ACGME-sponsored fellowships in interventional cardiology, advanced heart failure, electrophysiology and adult congenital heart disease, COCATS expectations are buffered by more robust Advanced Training Statements released independently by modality-specific task forces.

Multimodality imaging and critical care cardiology – nascent fields without formal training pathways – were inducted into COCATS 4 with basic milestones; refined training consensus statements are expected.

"Let us ... recognize that the area in-between is often up for discussion."

In his Bethesda Conference keynote, Hurst reflected that despite the scarcity of evidence to shape medical training, identifying the right approach is like "the feeling … when we hear a series of musical notes. All listeners will agree when a sequence of notes is pleasing to the ear or ... an unpleasant noise. Let us at least identify these extremes in training programs and recognize that the area in-between is up for discussion."

What should be up for discussion in future COCATS deliberations?

First, does the suggested division of time appropriately reflect the proportional values of each skill in the modern practice of cardiology?

Will we reach a point at which training is too broad at the expense of depth? Would trainees with different career goals benefit from early training pathways with distinct Level I requirements? Would streamlining general and advanced fellowships optimize training time or detract from integrative clinical acumen?

Second, could pre-training requirements, such as introductory echocardiography during residency, offload fellowship time and allow for more advanced skill acquisition?

Finally, is there a more refined approach for confirming competency? Perhaps assessment of a finite list of realistically attainable standard interpretation and procedural skills with near-perfect expectations might better reflect fitness for independent practice than a procedure log and adequate examination score.

I am optimistic that we will continue to refine our training paradigm with the same spirit of thoughtful innovation shaping the ever-changing landscape of clinical cardiology.

TABLE: COCATS 4 Task Force definitions for Level I, II, and III training across 15 subspecialties of cardiology

Click the image for a larger view

Note that procedural skills listed are not comprehensive. Expectations for medical knowledge, Systems-Based Practice, Practice-Based Learning and Improvement, Professionalism, and Interpersonal and Communication Skills, as well as detailed Patient Care and Procedural Skills expectations may be found in COCATS4 Independent Task Force documents.

*when applicable

†Some advanced fellowship curricula meet criteria to certify a transplant physician under United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS) criteria.

ABI indicates ankle-brachial index; ABIM, American Board of Internal Medicine; ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; ACHD, adult congenital heart disease; CBCCT, certification board of cardiac computed tomography, CBCMR, certification board of cardiac magnetic resonance; CBNC, certification board of nuclear cardiology; CCT, cardiac computed tomography; CIED, Cardiac implantable electronic devices; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise testing; CT, computed tomography; ECGs, electrocardiograms; EP, electrophysiology; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LV, left ventricular; MCS, mechanical circulatory support; MPI, myocardial perfusion imaging; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NBE, national board of echocardiography; PA, pulmonary artery; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PET, positron-emission tomography; PVI, physicians vascular intervention; RV, right ventricular; SPECT, single-photon emission computerized tomography; TEE, trans-esophageal echocardiography; TTE, trans-thoracic echocardiography.