Editor’s Corner | TAVR For One! But TAVR For All?

Interventional cardiology is now more than 15 years into the use of TAVR, ever since G. Alain Cribier, MD, performed the first case in April 2002.

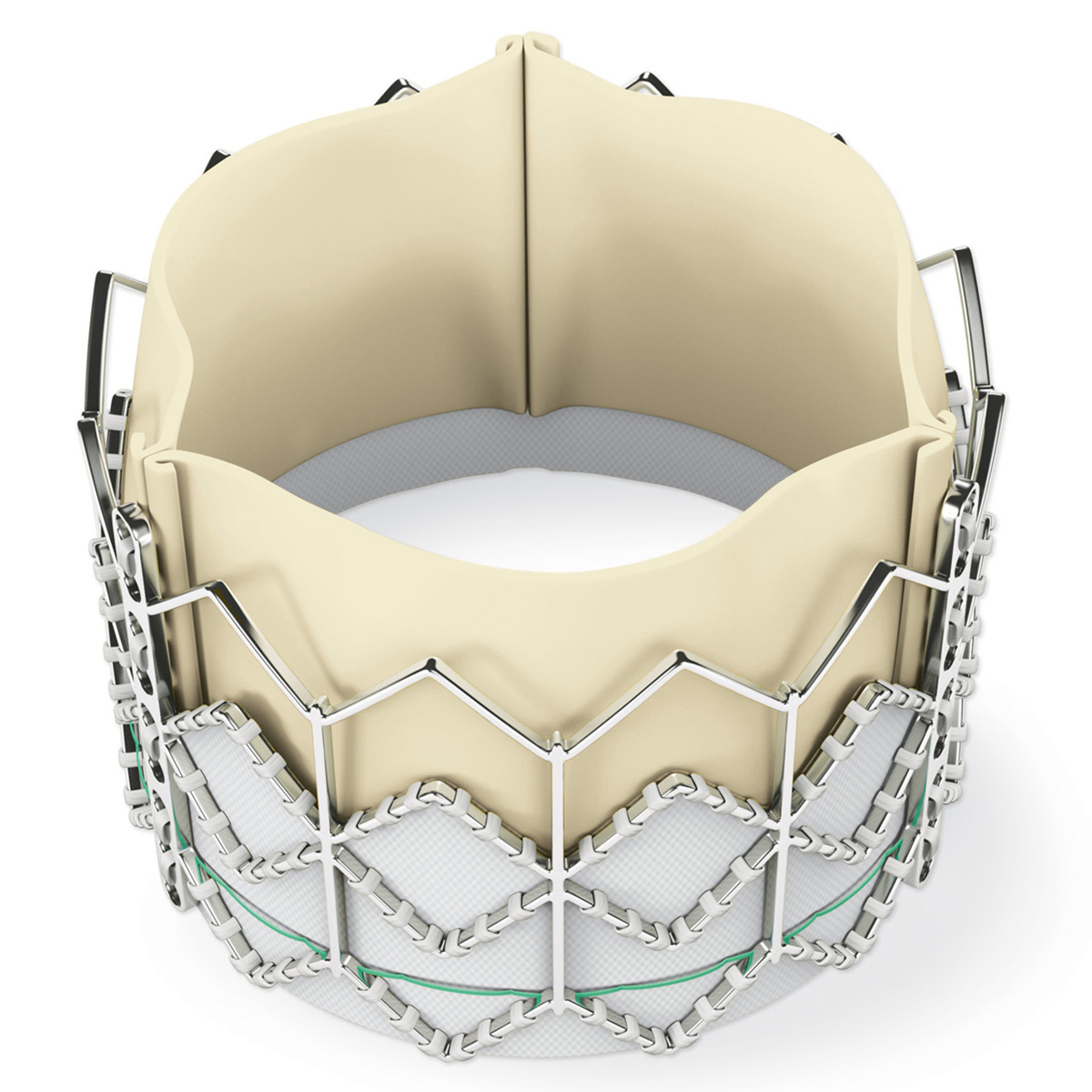

The devices are now pretty slick, and so-called second- and third-generation devices have appeared. Paravalvular leaks are now less of an issue. Some enthusiasts are simply saying that TAVR is now "for all."

The appeal of TAVR is clear. The procedure is quick, hospitalizations in straightforward cases are short, general anesthesia is not necessary, use of hospital resources is less, patients are up and about feeling better in less time, and so forth. As a result, the use of TAVR is expanding to lower (and lower) risk and younger (and younger) patients.

Is it time to hit the "pause" button and reflect?

In surveying the TAVR landscape, there are important issues still to be answered. Here are a few of them.

What did the randomized TAVR trials really tell us? PARTNER IB and the CoreValve Extreme Risk trials are no-brainers. TAVR was a clear winner over paired patients having medical therapy. But after those first trials, it gets a bit more complicated.

For patients at high risk (PARTNER IA, CoreValve High Risk) and intermediate risk (PARTNER 2A, PARTNER 2 S3i, SURTAVI) outcomes showed that TAVR and SAVR had equal outcomes.

In low-risk patients (PARTNER 3, CoreValve EVOLUT R), TAVR was noninferior to SAVR for the primary outcome of death, stroke and repeat hospitalization; in fact, TAVR showed superiority on additional analysis.

What drove the differences?

Mostly repeat hospitalizations in both trials. Death between SAVR and TAVR was not statistically significant in both trials, which was perhaps expected given the low risk of the patients.

Stroke was low (at roughly <3% for both SAVR and TAVR) but just favored TAVR statistically (embolic protection devices were not allowed in the trials).

The PARTNER 3 trial, based on these findings, concluded that TAVR through one year should be considered preferred therapy in low-risk patients, while the EVOLUT R conclusions were slightly more conservative: TAVR may be preferred strategy to surgery in low-risk patients. Importantly, 10-year follow-up is planned for both trials.

So, can we really conclude that TAVR is for all? Not so fast!

Before sending that 50-year old patient with aortic stenosis to the cath lab for her/his TAVR, consider these questions.

What age groups were actually studied in these trials? The mean age was approximately 73 years in both! Can these data be applied to patients 20 years or so younger? In PARTNER 3, only 7% of patients were <65 years. In EVOLUTE R only 6% were <65 years and 1.3% were <60 years.

What about pacemaker need? At one month, the Evolute R trial reported approximately 17% vs. 6% pacemaker use for TAVR and SAVR respectively. PARTNER 3 reported 6.5% vs. 4%, respectively. Meddling with the conduction system just below the aortic annulus has its price, but surgery still has the edge.

What about coexisting coronary disease? The exclusion criterion for extensive coronary disease in PARTNER 3 was a Syntax Score >32, and in EvolutR >22. Simply saying that higher degrees of coronary disease can be treated with concomitant/additional stenting has to be called into question – especially now that we have longer term follow-up of the Syntax trials that show better surgical bypass results in complex disease.

Where do we stand on the pesky bicuspid valve question? Most younger patients with aortic stenosis have bicuspid valves. Data are sparse and no randomized trials of TAVR vs. SAVR have been done. The self-expanding CoreValve was studied in such patients and the results presented at ACC.20/WCC.

The overall number was small (the study prospectively tracked 150 patients). On average, patients were 70 years old and had a Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score of 1.4%.

At 30 days, 1.3% of patients had died or experienced a disabling stroke. Of patients with a Sievers type 0 valve, roughly 15% had mild paravalvular leak after the procedure. That amount of leak in a 50-year-old might not be a good thing over the next 30 years.

Also, remember that many patients with congenital bicuspid valves also have associated proximal aortopathy. Interventionalists are eyeing that target for transcatheter therapy, but for now that is surgical territory.

What about valve size? If the annulus is too large or too small, a perfect transcatheter valve fit may be difficult. For small annular sizes, patient/prosthesis mismatch is a real issue. Especially for younger patients the hemodynamics of persistent outflow tract obstruction are long term issues.

SAVR surgeons are not immune to producing patient/prosthesis mismatch. In the CoreValve High Risk trial, severe patient/prosthesis mismatch occurred in approximately 21% of patients. But, if needed and possible, SAVR surgeons can enlarge the aortic annulus and outflow; TAVR cannot.

Bioprosthetic valves will, sooner or later, deteriorate. TAVR-in-TAVR can be performed, but at what risk? Data from the TRANSIT trial presented at TCT Connect 2020 indicate that in 172 patients from multiple international centers, the mortality at one year was 10%, with a cardiovascular mortality of about 6%.

Many such patients have few other options, but surgery can be performed in some. Perhaps the option of a mechanical prosthesis originally placed would have been a better option in young patients despite the long-term anticoagulation issue.

Finally, there are absolute contraindications to TAVR: endocarditis, pure aortic regurgitation in a valve that might be surgically reparable, severe left ventricular outflow tract calcification, surgical "other valve" considerations, etc.

TAVR is a great alternative to SAVR in lots of patients – especially the elderly and those with morbidities that directly affect surgical risk. However, there are still many unanswered issues about which we have limited data.

Should we accept that TAVR is for all? Not yet!

For many patients facing aortic valve replacement, it is still imperative that we confront what we know and what we do not know. A frank patient-physician discussion, or better a patient-heart team discussion is still an important part of the equation for all involved to outline the risk-benefit ratio of TAVR vs. SAVR for many.

Editor's Note: Click here for a feature on TAVR vs. SAVR and here to learn about the new ACC/AHA Guideline on Valvular Heart Disease.

Clinical Topics: Anticoagulation Management, Cardiac Surgery, Cardiovascular Care Team, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Valvular Heart Disease, Aortic Surgery, Cardiac Surgery and VHD, Interventions and Structural Heart Disease

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Middle Aged, Mitral Valve, Aortic Valve, Aortic Valve Insufficiency, Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement, Follow-Up Studies, Aortic Valve Stenosis, Biometry, Heart Valve Prosthesis, Endocarditis, Hemodynamics, Embolic Protection Devices, Risk Assessment, Stroke, Surgeons, Pacemaker, Artificial, Coronary Disease, Hospitals, Anesthesia, General, Hospitalization, Risk Factors, Anticoagulants, Family Characteristics, Cardiology

< Back to Listings