Cover Story | America's Melting Pot of Disparity: The Case of the Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) defines health disparities as "differences in the incidence, prevalence, mortality, and burden of diseases and other adverse health conditions that exist among specific population groups in the United States."

There may be no population for whom this term more applies than the Native peoples of Hawai'i, Guam, Samoa, and other Pacific Islands, populations who suffer disproportionately from, among other things, cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

"When Captain Cook and his crew first came to the Hawaiian Islands in 1778 they couldn't help but be impressed by the great hygiene practices and the overall health and well-being of our ancestors," says Joseph Keawe'aimoku Kaholokula, PhD, in an interview.

"One of his officers wrote in 1779, 'The natives of these islands are, in general, above the middle size, and well made; they walk very gracefully, run nimbly, and are capable of bearing great fatigue.' Unfortunately, today we have one of the highest rates of obesity in the country," he adds.

Kaholokula is chair of the Department of Native Hawaiian Health at the John A. Burns School of Medicine at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa in Honolulu, and a tireless warrior fighting to better understand and correct health disparities and inequities among Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (NHPI).

As with other Native populations, disparities in health status between NHPI and the general U.S. population have their roots in colonization, environmental destruction, foreign intrusion and racism.

"We've seen in our research that the experience of racism, or even the perception of racism, has adverse effects on physical and mental health, including increased systolic blood pressure," says Kaholokula.1 But that's just part of the story for NHPI. His research and that of others have traced the inequitable health status among NHPI to several complex and interconnected social determinants of health.2

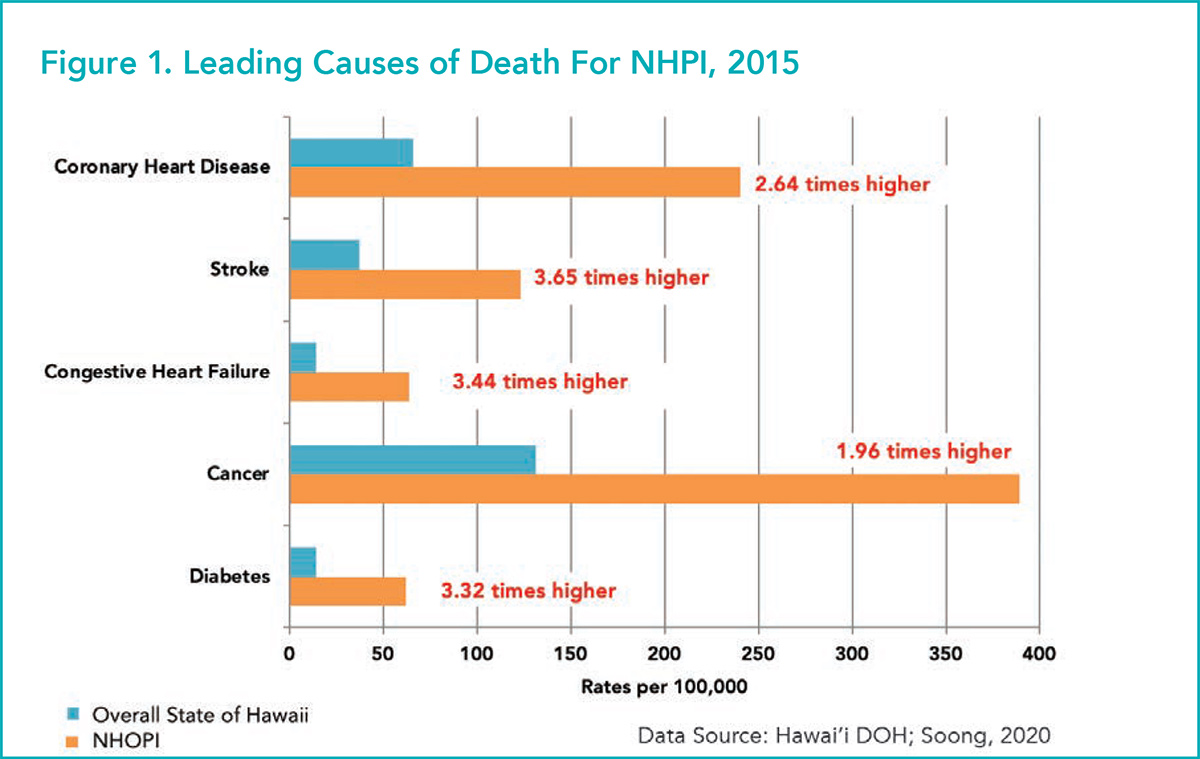

While the leading causes of death are similar, NHPI have higher rates of coronary heart disease, stroke and congestive heart failure, and are afflicted with these chronic conditions about a decade earlier in life. Even compared with the general population of Hawai'i, the differences are stark (Figure 1).

"What I see taking care of NHPI patients is definitely higher rates of risk factors – obesity, diabetes, hypertension – and also the concept of perceived risk where awareness of the risk doesn't quite get translated into action to improve them as early as possible," says Sanah Christopher, MBBS, FACC, an interventional cardiologist at Honolulu's Pali Momi Medical Center, part of Hawaii Pacific Health (HPH) network. HPH runs four main medical centers, three on Oahu and one on Kauai, and 70 satellite centers across the state. She finds this to be particularly true in her female patients.

Another issue, according to Christopher, is a delay in patients seeking health care. "I definitely see a trend of delayed presentation. I feel like it stems from either denial or a reticence to upset things by needing care," she says.

More than 60% of Native Hawaiians live in Hawai'i and another proportion in California. The states with the next largest NHPI populations at the time of the 2010 census were Washington, Texas, Florida, Utah, New York, Nevada, Oregon and Arizona. Together, these 10 states represent more than three-fourths (78%) of the NHPI alone-or-in-combination (with other ethnicities) population in the U.S.

Interestingly, NHPI are the fastest growing ethnic group in the U.S., growing by 61% from 2000 to 2019.3 NHPI number about 596,000 strong, representing 0.2% of the U.S. population. The Native Hawaiian population alone is expected to approach a million by 2060, driven by higher-than-average birth rates.

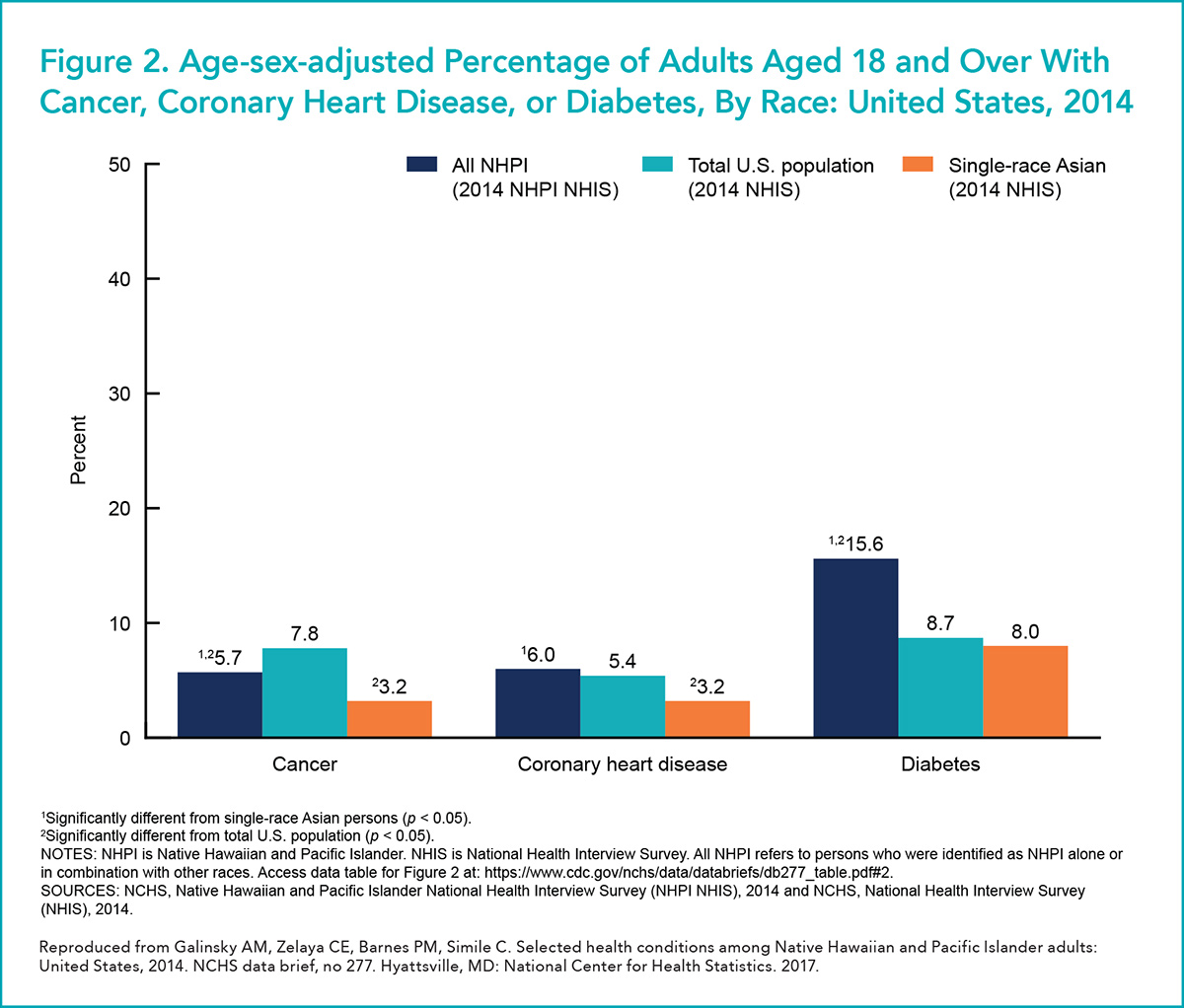

In 2014, the National Center for Health Statistics fielded the first federal survey focused exclusively on the population health of NHPI adults.4 In short, the key findings were that age- and sex-adjusted rates of NHPI adults reporting fair or poor health were higher than the rates for either the total U.S. population or those for single-race Asian American adults (15.5% vs. 12.0% vs. 9.2%, respectively; p<0.05 for both comparisons). NHPI also had higher adjusted rates of coronary heart disease and diabetes than the other groups, but lower rates of cancer, as compared with the general U.S. adult population (Figure 2).

Ola Hou i ka Hula, Heart Health Program

Much of the work done in the Department of Native Hawaiian Health at the University of Hawai'i is focused on the design and implementation of culturally-relevant programs and services to address disparities in NHPI.5

"We differentiate between programs that are culturally-adapted and culturally-grounded," says Kaholokula. "A culturally-adapted program is where you take an intervention that's been found to be efficacious in another population and adapt the intervention to the new population, or in this case, ethnic group, keeping the core curriculum in place but adding some culturally relevant aspects. Culturally-grounded programs are built around a cultural practice unique to an ethnic group as the core feature rather than as an afterthought."

A recent example of a culturally-adapted program saw a team of practitioners who have an affinity for Native Hawaiian people take care of Native Hawaiian patients admitted to the cardiac service line at Queen's Medical Center in Honolulu. Adverse events after PCI fell, along with 30-day readmissions, while quality indicators improved and became essentially the same as for other patient populations.6

The solution was a relatively simple one: the researchers used Native Hawaiian patient navigators who were experts in the cultural nuances and social context to help in the care of patients both in the hospital and after discharge.

The Kā-HOLO Project is a prime example of a culturally-grounded program.7 A five-year study funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Kā-HOLO evaluated the efficacy of a hula-based intervention on systolic blood pressure (BP) to reduce cardiovascular disease risk in Native Hawaiians with poorly managed hypertension.8

A total of 263 Native Hawaiians with uncontrolled hypertension (systolic ≥140 or ≥130 mm Hg with diabetes) and no cardiovascular disease at baseline were randomly assigned the hula-based intervention (n=131) or the education-only waitlist control (n=132). The intervention group received hula lessons and group-based activities for six months. All participants received a brief culturally-tailored heart health education before randomization.

Those assigned to the hula arm showed greater reductions in systolic (−15.3 mm Hg) and diastolic (−6.4 mm Hg) BP than controls (−11.8 and −2.6 mm Hg, respectively) from baseline to six months (p<0.05). At six months, 43% of intervention participants compared with 21% of controls achieved a blood pressure <130/80 mm Hg (p<0.001).

The 10-year cardiovascular disease risk reduction was twofold greater for the intervention group than the control group based on the Framingham Risk Score calculator. All improvements for intervention participants were maintained at 12 months.

Joseph Keawe'aimoku Kaholokula, PhD

"The participants love the program. It's become a support group for many where they help each other and share in family and holiday celebrations. It really shows how interventions can be more effective when built from the ground up for cultural relevance," says Kaholokula.

One limitation of the trial was the low number of male participants. Only 16% of the sample were men, despite special efforts to recruit men including having a male hula instructor and having Native Hawaiian male community leaders refer potentially eligible patients.

It's an unfortunate example of outside forces impacting how Native Hawaiian men view hula nowadays, according to Kaholokula. Traditionally, he explains, there's hula kahiko, ancient hula that has less swaying of the hips and is equally acceptable to men and women. Today there is hula auana, a more modern hula and the one people associate more with women (and a result of tourism industry promotion).

"Hula is our hallmark cultural practice in Hawai'i. It includes every element of our culture – it has language, music, spirituality. Hula holds our history and our genealogies, and the great deeds of our people over time," relates Kaholokula. "This program tapped into all of that."

COVID-19 Lays Bare Disparities

All the health issues among the NHPI have been exacerbated by COVID-19. Many Native Hawaiians work in essential services, in which case they've been exposed to a lot of COVID-19, or they work in tourism, especially in Hawai'i, in which case they've lost their jobs.

In Hawai'i, the NHPI have the highest per capita case rate of any group. And recent health department data show that Pacific Islanders, and in particular the Micronesian community, account for nearly 30% of cases, even though they make up only 4% of the population.

"The state, overall, has done well managing the spread of COVID-19," says Christopher. "In part, this was because we really needed to get things under control quickly and make sure our numbers didn't overwhelm our health care capacity. I'd say we're now one of the safer spots in the U.S. in terms of COVID-19."

On the continental U.S., things appear just as bad, although the problem is largely hidden from view. Most states don't disaggregate COVID-19 data for NHPIs. Of the 20 states that do, in the majority of states, including California, Arkansas, Washington, Oregon and Utah – all states with the largest NHPI populations – the NHPI community ranks first among ethnic groups for COVID-19 cases.9

Public health experts point to the usual underlying causes of disparities: high incidence of chronic disease, limited access to health care (about 20% of NHPI are uninsured, compared with 11.4% of non-Hispanic Whites), and they are more likely to be essential workers and living in shared housing, and lower socioeconomic status.10

"COVID has brought clarity to the inequities and shown how we need to continue working to level up and make sure our communities can aspire to many of the same things larger populations aspire to," says Kaholokula.

Living on an island has its perks. It's particularly advantageous if the goal is controlling spread of a pandemic virus. A few border controls and you get to be New Zealand. But it's not so great if your patient needs a heart transplant.

"We have realized that because of the distances involved, the logistics make it complicated to have a heart transplant program in Hawai'i," says Sanah Christopher, MBBS, FACC. Even a left ventricular assist device currently requires a trip to the mainland.

"Certainly here on Oahu we are well supported in terms of health care accessibility per capita. We have several cath labs, and there are cath labs on Maui and the Island of Hawai'i, which we call the Big island," says Christopher. Otherwise, island hopping by helicopter is common on the more remote Pacific Islands.

"It's when you go to the more remote and less populated islands that there is more of a challenge in ensuring care is readily available."

"Remoteness is a different concept when you're on an archipelago that is almost 2,000 miles from the nearest continent," she says. "However, our EMS are equipped with helicopters and I've never had concerns about getting a patient over to Oahu when needed."

The term "Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander" refers to people having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawai'i, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands. Pacific Islanders are a diverse population that differ in language and culture. They are of Polynesian (e.g., Native Hawaiian, Samoan, Tongan), Micronesian (e.g., Marshallese, Palauans, Chamorro, and Guamanians), and Melanesian (e.g., Fijian) ancestry and cultural backgrounds.

Although they share similar ancestry, each of the Pacific Islander groups are culturally distinct in language, histories and customs. They also differ in their relationships with the U.S.

Tonga, for example, an archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean comprising 169 islands (36 of which are inhabited) was a protected state of the United Kingdom until 1970, but is now a constitutional hereditary monarchy with representative elections.

In 1960, the year after Hawai'i became the 50th state, the decennial census questionnaire for Hawai'i included two separate response categories: "Hawaiian" and "Part Hawaiian." Later the term "Hawaiian" appeared on most state census questionnaires, with many states also adding the terms "Guamanian" and "Samoan."

"Hawaiian" and "Part Hawaiian" became check box options on the decennial census questionnaire soon after Hawai'i became a state in 1959. But by the 1980s, the U.S. Census Bureau had grouped them together with persons of Asian ancestry and created the category "Asian or Pacific Islander" (API).

This continued in the 1990s census where API was an explicit category, although respondents had to select one particular ancestry as a subcategory.

Then in 1997 the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) accepted a recommendation of the Interagency Committee for the Review of the Racial and Ethnic Standards to split the Asian Pacific Islander designations into two separate categories: "Asian" and "Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander."

The revised standards bring to five the number of minimum categories for data on race: American Indian or Alaska Native; Asian, Black or African American; Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander; and White. The new standards were effective immediately and reflected in the 2000 census documents.

These OMB standards obligate federal and state agencies but not private organizations. Data disaggregation is crucial to really understand the needs of the community and allocate resources effectively, says Joseph Keawe'aimoku Kaholokula, PhD.

"Lumping together Asians with NHPIs causes a lot of distortion in the data that can mask important differences," notes Kaholokula. "For example, Native Hawaiians have some of the highest rates of obesity, but many Asian subgroups have much lower rates, so the law of averages kicks in and your data are not really meaningful."

As a salient example, the American Heart Association's Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics still combine the groups.11 In the 2021 Update, the designation "Non-Hispanic Asian Males (or Females)" is used in several places, footnoted with the caveat that this "includes Chinese, Filipino, Hawaiian, Japanese, and other Asian or Pacific Islander people."

"I mean, this really doesn't tell you much, does it? It's pretty arbitrary," says Kaholokula.

References

- Hermosura AH, Haynes SN, Kaholokula JK. A preliminary study of the relationship between perceived racism and cardiovascular reactivity and recovery in native Hawaiians. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2018;5:1142-54.

- Mau MK, Sinclair K, Saito EP, et al. Cardiometabolic Health Disparities in Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders. Epidemiol Rev 2009;31(1):113-129. doi:10.1093/ajerev/mxp004

- Budiman A, Ruiz NG. Asian Americans are the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in the U.S. Pew Research Center. Available here. Accessed April 13, 2021.

- Galinsky AM, Zelaya CE, Barnes PM, Simile C. Selected health conditions among Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander adults: United States, 2017. NCHS Data Brief 2017:277:1-8.

- Kaholokula JK, Ing CT, Look MA, et al. Culturally responsive approaches to health promotion for Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. Ann Hum Biol 2018;45:249-63.

- Cook A, Grothaus CT, Gutierrez CE, et al. Closing The Gap. Disparity In Native Hawaiian Cardiac Care. Hawaii Med J 2010;69(5 suppl 2):7-10.

- Kaholokula JK, Look MA, Wills TA, et al. Kā-HOLO Project: a protocol for a randomized controlled trial of a native cultural dance program for cardiovascular disease prevention in Native Hawaiians. BMC Public Health 2017;17:321.

- Kaholokula JK, Look M, Mabellos T, et al. A cultural dance program improves hypertension control and cardiovascular disease risk in Native Hawaiians: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med 2021;(kaaa127).

- NHPI COVID-19 Data Policy Lab Dashboard. Available here. Accessed April 20, 2021.

- Kaholokula JK, Samoa RA, Miyamoto RES, et al. COVID-19 special column: COVID-19 hits Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities the hardest. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf 2020;79:144-6.

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2021 Update. Circulation 2021;143:e254-e743.

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, COVID-19 Hub, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Prevention, Acute Heart Failure, Hypertension

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Asian Americans, Birth Rate, Cardiovascular Diseases, Blood Pressure, Cause of Death, Chronic Disease, Coronary Disease, Cost of Illness, Control Groups, COVID-19, Curriculum, Censuses, Delivery of Health Care, Diabetes Mellitus, Ethnic Groups, Fatigue, Guam, Hawaii, Health Education, Heart Failure, Housing, Hospitals, Hypertension, Incidence, Language, Medically Uninsured, Medicine, Mental Health, National Center for Health Statistics, U.S., National Institutes of Health (U.S.), Neoplasms, Oceanic Ancestry Group, Obesity, Patient Discharge, Pacific Islands, Perception, Patient Navigation, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Prevalence, Racism, Random Allocation, Risk Factors, Risk Reduction Behavior, Self-Help Groups, Social Class, Social Determinants of Health, Social Environment, Spirituality, Stroke

< Back to Listings