Feature | Asynchronous Visits: Our Experience With an Underserved Rural Population

Figure 1 Confluence Health in North Central Washington Confluence Health is based in Wenatchee, WA, with a series of outreach clinics in communities up and down the Columbia River.

Figure 1 Confluence Health in North Central Washington Confluence Health is based in Wenatchee, WA, with a series of outreach clinics in communities up and down the Columbia River.

As COVID-19 strains the U.S. health care system in countless ways, rural areas are disproportionately feeling the impact. Health disparities in rural America have persisted for decades due to a large government payer mix, fewer providers and limitations in access. Recent data have suggested higher age-adjusted cardiovascular mortality in rural areas vs. urban and suburban regions.1 Concurrently, a significant nationwide cardiologist shortage is expected by 2024.2 As alternative payment methods for care delivery take hold and virtual care becomes more accepted, it is vital to leverage technology to improve cardiovascular health.3

Confluence Health serves a large geographic region of North Central Washington (Figure 1). Our patient mix is diverse, with a large proportion of elderly, migrant and Native patients. Advanced technology such as broadband is surprisingly available in this area. However, social determinants often limit access to basic technology for the average patient. Like most rural areas, access to health care and especially specialty care can be limited. In our region, some patients may drive more than 200 miles roundtrip to see their cardiologist, often forcing financial, occupational and other logistical constraints. With these challenges in mind, we are leveraging tools within our electronic health record (EHR) to better connect with our patients with heart failure (HF) and coronary artery disease (CAD). These tools allow frequent contact between patients and their care team in a time-efficient manner, which includes screening patients to determine whether follow-up care should be in person and with a cardiologist or primary care physician.

Asynchronous Visits

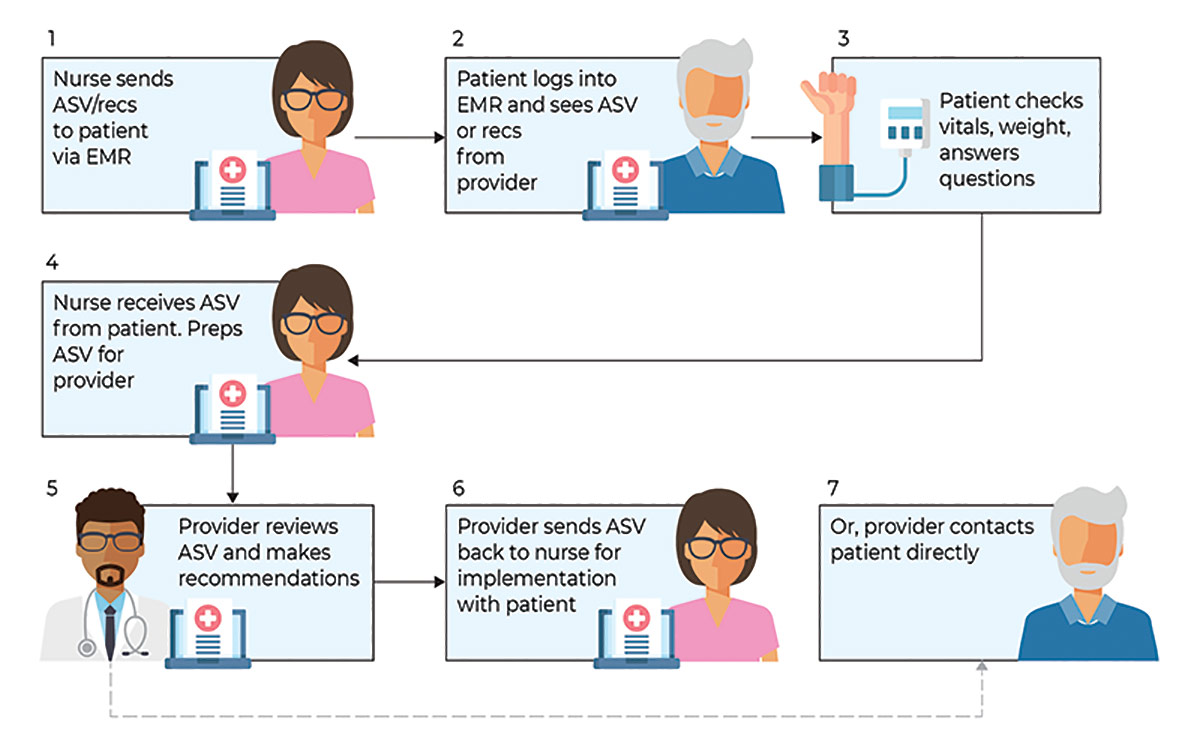

Asynchronous visits (ASVs) are a viable alternative to clinic or real-time synchronous telemedicine video or phone visits, especially in underserved areas. Typically sent to patients via an EHR-connected patient portal, ASVs are questionnaire-driven, tailored to a disease state, and formatted to be easy to understand (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Graphic by Nizar Krayem Design

While ASVs are a relatively new concept in chronic disease management, elements of telehealth used to monitor vital signs, weight, labs and symptoms are not new for management of CAD4 and HF.5 ASVs allow more frequent encounters with sicker patients requiring more focused monitoring or medication titration.

We developed our own ASV questionnaires for HF and CAD. Questions were modeled from typical information assessed by providers at clinic visits for these conditions and reviewed to ensure an appropriate health literacy level, including verifying readability and grade level using an online tool (readabilityformulas.com). Finalized versions of the ASV were provided to IT staff to formulate a patient questionnaire within the Epic MyChart EHR.

A workflow was developed with a cardiology registered nurse to send the questionnaires to patients deemed eligible by the cardiology provider. Returned questionnaires were reviewed and processed by the nurse, with relevant labs and clinical information added, and sent to the designated provider for review.

Developing, Testing Our HF ASV

Our journey with cardiology virtual care began in 2016, with the development of a telemedicine program to better reach patients in outlying areas. Rather than drive two hours to our clinic, patients could drive a few minutes to their local clinic and connect with their cardiology provider via video conference, receiving the usual nursing check-in, vital signs and medication reconciliation as with a clinic visit.

Our sickest, most vulnerable patients with conditions such as HF and atrial fibrillation benefitted the most from these virtual encounters because of the more frequent specialty contact. We learned that the nurse check-in along with some basic triage questions made a significant difference for both patients and providers. Interestingly, while the video interaction with the provider was helpful for many patients, in many ways, the connection with the nurse seemed to have the greatest impact.

A deep dive into data from a retrospective chart review of 528 patients in the Health Alliance Northwest Medicare Advantage program with a HF-related diagnosis, conducted in 2018, revealed a high rate of acute care utilization: 40% had at least one emergency department (ED) visit in the previous 12 months, and 10% had three or more. We also learned that many of our HF patients lived in remote areas with less in-person access to cardiology care or had difficulty traveling to the clinic because of logistics or comorbidities. Therefore, to better serve these patients within a capitated model and considering our limited nursing resources, we developed and tested an HF ASV with a small sample of patients active in the EHR patient portal.

Our initial goal was to evaluate metrics such as patient response rate, response time, accuracy of completion and turnaround time. We also examined trends in the delivery that may have impacted patient adoption rates, efficiency and process sustainability.

What were the lessons learned in our test cohort? The value of patient education about the rationale for more frequent virtual contact and the need for repeated electronic prompts to nonresponders. In response to this, we developed a patient education pamphlet to help them better understand the benefits of and opportunities to connect with their providers using ASVs.

The test also led to an optimized nursing workflow and a standardized format for presenting data to the provider that was captured by the nursing screen of patient responses during the ASV. Automating the addition of recent labs and adding an updated medication list to the ASV enabled providers to quickly frame the context of the patient's responses and provide recommendations. Reassuringly, most patients were comfortable with ASVs and communicating this way between scheduled clinic visits.

Developing, Testing Our CAD ASV

Our experience with HF was leveraged to create an ASV for our patients with CAD. Many of these patients are clinically stable and theoretically the follow-up to review labs and a standard set of symptoms could be assessed with a questionnaire.

Recognizing an opportunity to improve timely, in-person access to specialty care for sicker patients, we designed the CAD ASV to help us identify patients with symptoms who would benefit from an in-person cardiology evaluation, while ensuring our stable, asymptomatic patients had contact with their cardiology provider, but in a virtual format We tested the CAD ASV to determine if the questionnaire was relevant, accurate and could either obviate a clinic visit or facilitate care at the time of a clinic visit. Over a three-month period, we identified a cohort of 48 Medicare Advantage patients with known CAD, active in the EHR patient portal and with a scheduled cardiology clinic visit (an ASV was sent one month before the appointment). Most of our patients without serious comorbidities, such as cardiomyopathy or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, were asymptomatic.

Notably, of patients reporting symptoms via the ASV, only one-third had symptoms noted in their clinic visit documentation, suggesting symptoms reported in the ASV were either transient or not deemed important by the patient or provider. This underscores the limitations of a questionnaire to tease out concerning (from atypical) symptoms and highlights future opportunities to improve the breadth and timeliness of the ASV. Medication-related side effects, such as with statins, were not commonly reported in the ASV or at the patient visit.

When asked if the ASV could replace the annual clinic visit with their cardiologist, most of the CAD patients in this test were unwilling or neutral. This was an important finding, given our initial premise that the CAD ASV could replace in-person visits, and underscores the need to better understand the intangible factors related to in-person visits not addressed by the ASV. Similar with the HF ASV, the CAD ASV was beneficial for patients who need more frequent interaction between visits.

Expanding Our ASV Portfolio

In our busy clinical cardiology practice serving a large rural area, ASVs for a cross-section of patients in one Medicare Advantage program have been a promising adjunct to the care of patients with HF and CAD. In fact, we're continuing both ASVs, because of the successful pilots, and we're expanding our program to include an ASV for hypertension. Additionally, we're creating an ASV toolkit for our organization, which we hope to share with other organizations. Our lessons learned may prove helpful to clinicians practicing in any location given the current health care environment, as more care goes virtual.

For the pilots, our numbers were small because the goals were to understand our community and optimize care. Nonetheless, patient engagement and provider commitment were high. Our initial response rate was <50% for both ASVs. Based on patient interviews, we modified our approach to improve responses, including education interventions and a closed loop feedback in partnership with our clinic nurse for patients who did and did not respond. We also integrated recommendations to improve utilization and adherence to the patient portal, aligning with organizational goals for patient use of MyChart. From our data, it seems clear that patient education about the technical process and purpose of the ASVs are key to successful implementation moving forward.

ASVs are an important tool in the management of CAD and especially HF, which often requires close follow-up, home monitoring of metrics such as weight and blood pressure, and frequent medication titration. While the information gained from a typical ASV questionnaire is similar with that elicited with nursing triage or in the clinic, it more directly and consistently frames the clinical context and fosters engagement at a time convenient for the patient. Furthermore, additional clinical data, such as labs, can be obtained by nursing staff before the cardiologist's review of the ASV. Although ASVs may not allow us the clinical nuance often teased out at a clinic visit, they can serve as "advanced triage" with a patient who may otherwise have been a no-show or lost to follow-up.

Notably, the goals of the ASVs differed a bit for the two common cardiac disease states we studied. For CAD, stable patients were triaged with the ASV for symptoms, thereby prompting a clinical evaluation. With HF patients, who are often sicker, ASVs allow more frequent contact between scheduled visits, with a focus on symptoms and diuretic response to identify and manage potential decompensation.

The ASVs also identified patients who were seen in the ED or hospitalized at outside facilities, fostering notification of recent changes in clinical status that may otherwise have gone undetected. For CAD and HF, ASVs allow easier touch points for care and improve coveted clinic access for all patients.

Questions within the ASV must be carefully vetted and modified over time, we've learned, including innovation in the framing of questions and data gleaned from an encounter.

Facilitated self-service in medicine, as represented in our approach to the ASV, is evolving and likely necessary. Fundamental approaches to managing chronic disease have been unchanged for years, with acute care occurring in hospitals and chronic care in office visits. Treatment options have evolved, but the ubiquity of smartphone technology and the EHR have not resulted in gains in efficiency, cost or patient/provider satisfaction. In fact, just the opposite is true.

The ASV takes us towards facilitated self-service, where patients can begin to handle chronic issues outside the office setting, which is often a choke point for access.6 HF and CAD management are often algorithmic, allowing more efficient and less expensive asynchronous care.

As health care becomes more value-driven, reimbursement for care outside the doctor's office will lead to innovation and convenience. Our experience with ASVs has revealed that while technology can be used and seem to contribute to better outcomes, patients still want face-to-face interaction with their providers. A better framework for ASVs may be to envision them as tools to be deployed at specific times for specific patients at specific points in their disease trajectory.

Social and financial determinants will continue to be a barrier, but ultimately, trying innovative methods to connect with patients will lead to more trust and improved outcomes. Indeed, we've learned that a very small percentage of our Medicare Advantage patients were actively engaged in our patient portal, likely indicating limitations in using or having technology to connect. This alone is an important consideration as more data on virtual care emerge.

In rural Washington, we have shown that ASVs are a foundation from which we can build better options in our virtual world, tailored towards the individual patient experience. As health care evolves and virtual processes improve, embracing asynchronous communication as a bridge to true value-based care will reduce barriers, improve utilization, and empower patients and providers.

This article was authored by Katie Bates, DNP, ARNP, CHFN, Confluence Health, Wenatchee, WA, and CV Team Liaison, ACC Washington Chapter; Benjamin Titus, BS, 4th Year Medical Student, University of Washington, Seattle, and member of ACC's Medical Student Council; and Gautam Nayak, MD, FACC, (@GautamNayakMD), Confluence Health, and governor/president, ACC Washington Chapter.

The authors thank Kim Fischer, Mark Dronen, Dianna Osborne, RN, Kiley Feeney, RN, and Miracle Israel, DNP, for their tireless efforts in helping us develop our ASV program at Confluence Health.

References

- Cross SH, Mehra MR, Bhatt DL, et al. Rural-urban differences in cardiovascular mortality in the us, 1999-2017. JAMA 2020;323:1852-4.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. National and Regional Projections of Supply and Demand for Internal Medicine Subspecialty Practitioners, 2013-2025. Available here.

- Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;139:e56-e528.

- Blasco A, Carmona M, Fernandez-Lozano I, et al. Evaluation of a telemedicine service for the secondary prevention of coronary artery disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2012;32:25-31.

- Bui AL, Fonarow GC. Home monitoring for heart failure management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:97-104.

- Asch DA, Nicholson S, Berger ML. Toward facilitated self-service. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1891-3.

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Rural Population, Office Visits

< Back to Listings