Feature | A Workforce in Crisis: Navigating the Cardiovascular Clinician Shortage

The cardiovascular medicine workforce is facing a critical shortage that threatens to undermine patient care across the country. Physicians along with the entire cardiovascular care team are under unprecedented strain, creating a crisis that demands innovative solutions.

The problem is not new. The ACC has been working towards solutions for nearly two decades, with past presidents warning of this workforce shortage since 2004.1 Yet aging patient and provider populations, sicker patients, the increased complexity of cardiovascular medicine, greater regulatory burdens, clinician burnout and the hyperspecialization of the field brings it to the crisis level, says Thomas M. Maddox, MD, SM, FACC, who chairs the College's Task Force on the Cardiovascular Workforce.

The shortage is most acute in the general cardiology arena, says Ginger Biesbrock, DSc, PA-C, FACC, who also sits on the workforce task force. "Many of our fellows get through their three-year clinical cardiology fellowship and then go on to subspecialty training. So, we end up heavy on the proceduralists and more advanced clinicians," creating access issues for patients. A 2022 survey showed a 26% increase in average wait time for a general cardiovascular visit ("heart checkup") since 2017 (26.6 days).2

Part of the trend toward hyperspecialization stems from financial incentives, she says, highlighting a need for improved reimbursement. "At a fair market value, the extra education usually lends itself to higher earning potential," she says. "But our pipeline for patients, our front door to ambulatory practices, is general cardiology." Specialization is necessary, agrees Maddox, given the increasing complexity of the field. "But we need general cardiologists to manage the intake," he adds.

Supply vs. Demand

At its core, the cardiovascular workforce crisis represents a fundamental imbalance between supply and demand. On the supply side, barriers to physicians entering cardiology, especially general cardiology, include the years of training required, perceived and actual work/life imbalances and increasing administrative burdens. At the same time, demand is rising given an increasingly older and sicker patient population.

"We've never seen patients this sick before," says Maddox. In the past, they would have died. Today, however, "we're better at keeping them alive." In fact, the prevalence of chronic cardiovascular disease throughout the world has doubled in the past 20 years, driven by an aging population and advancements in cardiovascular treatments.3

According to projections from the College, the American Heart Association and MedAxiom, the ratio of cardiovascular patients per cardiologist is expected to increase from one for every 1,087 patients in 2025 to one for every 1,700 patients by 2035. In 2019, 26.5% of cardiologists were 61 or older; by 2031, MedAxiom estimated that retirements coupled with the fixed number of fellows would lead to a loss of 547 cardiologists per year.

This has significant consequences on patient outcomes. One study of 3,142 counties in the U.S. found that 62% had no cardiologists. Those counties had significantly higher age-adjusted mortality rates than counties with cardiologists, including higher rates of cardiovascular disease-related mortality. A density of about 13 cardiologists per 100,000 was associated with the lowest rates of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality, yet just 112 counties had such a supply.4

Burning Out

A critical factor in the workforce crisis is burnout, which affects clinicians in most specialties, not just cardiology.

"Clinician well-being is a big issue in medicine at large," says Laxmi S. Mehta, MD, FACC, who chairs the ACC's Membership Committee and has been long-time leader of the College's clinician well-being efforts. "It has been an ongoing issue for years, but it gained significant attention and recognition during the pandemic."

Indeed, one large U.S. survey conducted during the pandemic found 59% of cardiology nurses, 46% of CV Team members and 40% of physicians reported burnout. Between 23% and 45% expressed a desire to leave their jobs. The more valued the provider felt, however, the less likely they were to report burnout or a desire to quit.5

Other studies find similarly high percentages of cardiologists, cardiac imaging specialists and cardiovascular fellows reporting symptoms of burnout.6-7 A 2019 survey of College members found more than a third reported being burned out and nearly 44% were stressed.6 In addition, a more recent Medscape survey of 9,100 physicians from 29 specialties found cardiologists near the bottom in terms of happiness outside of work.8

There are numerous contributors to burnout, including insufficient income; work-life imbalance, particularly among women; a hostile work environment; the lack of control and autonomy that's occurred with the shift from independent to corporate practices; computerization; and bureaucracy.8 In the Medscape survey, 65% of cardiologists cited bureaucratic tasks as the top contributor to burnout.8

"People feel very stressed," Mehta says. "Some are experiencing anxiety and others depression related to work stress or pressures. This environment can be challenging." Burnout and stress lead to disengagement, which, she says, affects patient outcomes.

Finding Solutions

"The CV workforce crisis is a multifaceted challenge that requires a combination of innovative College solutions, broader public health policy changes, federal and state advocacy to support training and to address social determinants of health, and partnership with a variety of other CV and medical professional societies," wrote Maddox and colleagues in a Leadership Page in January 2024 in JACC.9 "There is no 'magic bullet' or speedy solution. However, the College, with its more than 56,000 members and expertise in education, advocacy, innovation, and practice management, contains the strategic vision, talent, and long-term orientation to lead in meeting this challenge."

Addressing the cardiovascular workforce crisis requires a multifaceted approach, Maddox says, many of which the College is pursuing. This includes:

Changes in training and career pathways. This includes advocating for shorter training periods by combining general and subspecialty training; increasing residency and fellowship slots; providing part-time opportunities for older physicians; and supporting immigration efforts to bring more foreign graduates into the workforce. The College spelled out several recommendations and opportunities for more career flexibility as part of its 2022 Health Policy Statement on Career Flexibility. Some community hospital systems are also starting their own fellowship programs, says Maddox.

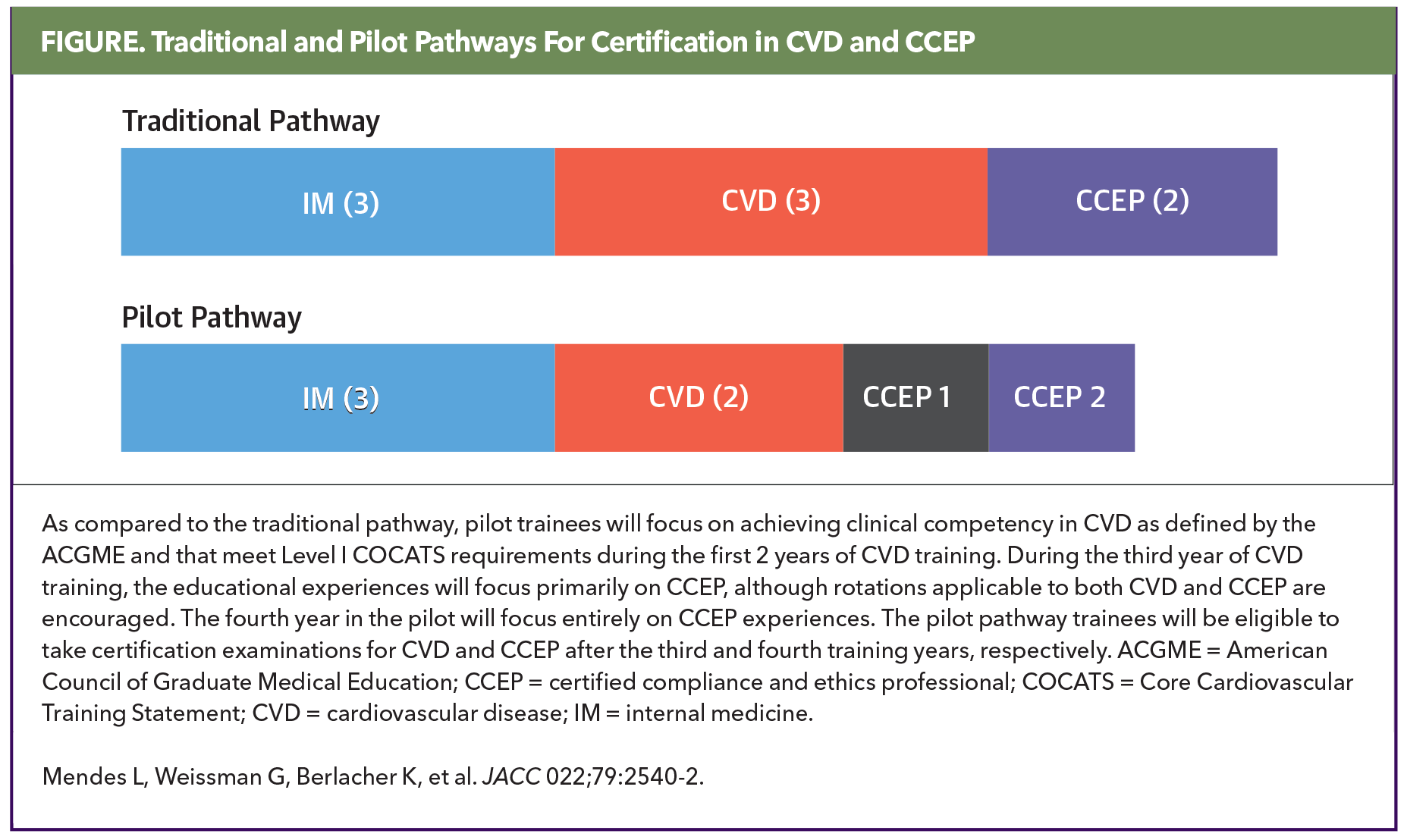

In 2023, the College and the Heart Rhythm Society launched a pilot program that allows trainees to complete their cardiovascular/clinical cardiac electrophysiology (CCEP) programs in four instead of five years (Figure).10 It could serve as a model for other cardiovascular specialties.

Promote and incent careers in general cardiology. This includes career pipeline development efforts like the ACC's Young Scholars Program, Internal Medicine Program and Clinical Trial Research Program, many of which are funded thanks to the generous philanthropic contributions from ACC members around the world. "The College is also working with cardiology training program directors to ensure that the benefits of careers in general cardiology are appropriately highlighted," says Maddox.

Drive payment reform and incentives alignment. This a key advocacy priority for the College, which continues to pursue value-based reimbursement at the state and federal level working with lawmakers, payers and other societies.

Provide well-being resources to support the CV team's physical and mental health. Biesbrock stresses that addressing burnout begins with the organizational leadership and culture. "Both physician leaders and administrative leaders need to understand the challenges we're facing in 2025 and keep their finger on the pulse of workforce so they know what's going on and how people are doing." That means engagement surveys; rounding throughout clinics and hospitals; and understanding the patient experience. "Because if the experience isn't great for the patients, it's probably not great for those providing the care," she says.

Mehta calls for a holistic approach to well-being. "At my organization we talk about a culture of wellness," she says. Organizations also need to consider how to optimize people's workdays so they spend more time practicing medicine and less time on administrative tasks.

This is where technology comes in, she says, such as artificial intelligence (AI) replacing scribes in the examining room.

Partner to better manage CV disease. The College is quite active in this area, Maddox says. Public health partnerships addressing and promoting prevention, like the Rural Community Health Initiative pilot program in New Mexico and the CardioSmart Caring Hearts effort, are key to driving change in communities in the U.S. and around the world.

Promote team-based care with members of the CV Team. One study focused on the primary care physician shortage estimated that half of preventive and chronic disease management could be provided by CV Team members and allied health professionals, with one team of a physician and full-time CV Team member caring for up to 2,500 patients. This offers a model for general cardiology.11

Culture, Leadership and Equity Key to Addressing CV Workforce Crisis

However, says Biesbrock, bringing allied health professionals, most of whom are trained in primary care, into cardiology practices requires systematic onboarding. "We need the appropriate infrastructure in which to develop cardiovascular skills and competencies and then the appropriate structure in which to work effectively as part of the team, which means clearly defining roles and responsibilities."

Teams can also improve the quality of the care provided and address some of the issues contributing to burnout, Mehta says. "The diagnoses are more nuanced and there are many more opportunities for care. It's hard to stay on top of everything. That's where having the right team work with you is going to be critical. As an individual, we can accomplish some but as a team we can accomplish so much more. The sum is greater than each individual part."

Hope For the Future

Maddox is far from pessimistic about the future of the cardiology workforce. "The first step of any issue is to admit that you have a problem," he says. "I think there is a growing awareness of these issues and the unsustainability of the path we're on."

He also thinks that people are now recognizing that clinician wellness is critical to a healthy workforce and that if it's not addressed, "that will be a problem."

But people need to act, he says. "If we don't do anything or ignore it, we are on a bad trajectory in terms of supply."

References

- Fye WB. Cardiology's Workforce Shortage. Circulation. 2004;109(7):813-816. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000118641.54694.4C

- AMN Healthcare. Survey of Physician Appointment Wait Times and Medicare and Medicaid Acceptance Rates. August 8, 2024. Available at: https://www.amnhealthcare.com/amn-insights/physician/whitepapers/survey-of-physician-appointment-wait-times/. Accessed April 30, 2025.

- Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(25):2982-3021. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010

- Minhas AMK, Parwani P, Fudim M, et al. County‐Level Cardiologist Density and Mortality in the United States. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2023;12(23):e031686. doi:10.1161/JAHA.123.031686

- Mallick S, Douglas PS, Shroff GR, et al. Work Environment, Burnout, and Intent to Leave Current Job Among Cardiologists and Cardiology Health Care Workers: Results From the National Coping With COVID Survey. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2024;13(18):e034527. doi:10.1161/JAHA.123.034527

- Mehta LS, Lewis SJ, Duvernoy CS, et al. Burnout and Career Satisfaction Among U.S. Cardiologists. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(25):3345-3348. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.04.031

- Koval L. Physician Lifestyle and Happiness Report 2023. Medscape. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/sites/public/lifestyle/2023. Accessed April 30, 2025.

- Alexandrou M, Simsek B, Rempakos A, et al. Burnout in cardiology: a narrative review. J Invasive Cardiol. 2024;36(5):10.25270/jic/23.00292. doi:10.25270/jic/23.00292

- Maddox TM, Fry ETA, Wilson BH. The Cardiovascular Workforce Crisis: Navigating the Present, Planning for the Future. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024;83:466-9.

- Mendes, L, Weissman, G, Berlacher, K. et al. Competency-Based Alternative Training Pathway in Cardiovascular Disease and Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology. JACC. 2022 Jun, 79 (25) 2540–2542. 10.1016/j.hrcr.2023.06.002. PMID: 37492051; PMCID: PMC10363459.

- Altschuler J, Margolius D, Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Estimating a reasonable patient panel size for primary care physicians with team-based task delegation. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(5):396-400. doi:10.1370/afm.1400

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, Prevention, Stress

Keywords: Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications, Burnout, Psychological, Patient Care Team, Workforce