Feature | A Framework to Integrate Popular Media into Cardiovascular Medicine

Google, WebMD, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram – the internet possesses an endless wealth of information that is easily accessible to individuals in every corner of the world.

But how does one know whether information accessed through the internet is accurate?

Medical information is widely disseminated through health care and social media websites, among many other sources, and many individuals seek out these resources to help guide their health care decision-making.1,2

Accessing accurate and high-quality medical information has become a challenge in today's era of self-purported experts propagating medical information, or likely misinformation, with limited evidence-base over the Internet.3,4 This has become even more important in the current era of COVID-19 when misinformation can have a significant health impact.

Media portrayal of medical treatments, procedures and health care experiences has a profound impact on patient perceptions and preferences. An estimated 40% of individuals stated that social media impacts their health care decisions and 90% of young adults indicated they would trust information shared by others on social media networks.2 The effects of popular media on health care decisions has had mixed consequences.

The American Heart Association's (AHA) Rise Above Heart Failure campaign was promoted on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, among other popular media outlets, with the goal of increasing public awareness on the impact of heart failure and to decrease heart failure hospitalizations. This resulted in a substantial positive impact on community awareness.

Yet, we've all seen adverse effects of patients accessing media sources with questionable reliability. Controversies on the efficacy and safety of statin therapy and vaccinations are just a few examples of the detrimental effects that social media can have not only on public health perceptions, but also on health care decisions that have direct and substantial consequences.5-7

Click the image above for a larger view. Reproduced with permission from Springer Nature from Curr Atheroscler Rep 2019;21:43.

Click the image above for a larger view. Reproduced with permission from Springer Nature from Curr Atheroscler Rep 2019;21:43.

The importance of disseminating vetted sources of medical information to preserve the clinician-patient relationship and shared decision-making has recently been highlighted in the scientific community.3,8,9

As a medical community, it is our responsibility to advocate for patients by providing an accessible stream of high-quality, evidence-based materials that enable them to independently weigh pertinent health care information to make decisions.

With a large number of people relying on the internet and popular media outlets for medical information, a reliable framework is needed to ensure that the needs of patients and health care professionals alike are being met.

Beyond its impact on the general public, social media platforms have become a venue for medical professionals to interact with each other and foster a sense of community. Roughly 65% of health care professionals report using social media for professional activities including networking, keeping abreast of scientific news and professional development.10-12

Cardiology-specific Twitter hashtags such as #Cardiotwitter, #EchoFirst, and #RadialFirst have helped to unify thousands of clinicians via social media where educational materials from institutional programming, conferences and publications can be shared with ease.13 Undoubtedly, this creates an additional layer of complexity when structuring professional interactions between health care professionals and patients.

Effects of Popular Media on the COVID-19 Pandemic

A recent example of the widespread effects of popular and social media that resonates is the COVID-19 outbreak. This global pandemic is catching unprepared health care systems off guard and devastating millions. As COVID-19 ravages people across continents, numerous accounts of "treatments" and "cures" have surfaced from self-purported experts.14,15

In the absence of clinical trials or sound evidence, these so-called "miracle treatments" such as vitamin infusions, homeopathic cures, breathing exercises and so forth are touted as the cure-all.

The hysteria created by misinformation contributes to a great deal of anxiety, mass hoarding of essential supplies and critical shortages of personal protective equipment for health care workers on the front lines. This misinformation can have devastating consequences given that the population's vulnerability is very high.

In several instances, inappropriate use of medications and suggested treatments has even resulted in unintended poisonings and death.16 As misguided information permeates through the internet and social media platforms, it often overshadows the voice of clinical experts and professional organizations, thus creating confusion among patients and health care professionals alike regarding recommendations for personal protection and effective treatments.

The physical, emotional and socioeconomic toll of the COVID-19 pandemic continues to be felt across the world and has permanently altered the fabric of society. This global pandemic is one of the rare times in history where nearly the entire world's population has been affected regardless of race, gender, creed, socioeconomic status or ethnicity.

If we take a step back and revisit the steps that may have led to the present predicament with widespread shortages, one may consider the notion that the dissemination of current and accurate information regarding virulence, treatments and protective measures may have prevented some of the panic and hoarding that has ultimately led to detrimental effects on society – death, devastation and grief.

It is in times of great vulnerability that fear manifests itself in rational and irrational ways and that the true power of popular and social media is realized. It is in times like these that having a sound, unified voice of reason based on scientific evidence to guide those who are anxious, confused and uninformed is of the utmost importance.

Framework For Optimizing Popular Media Experience

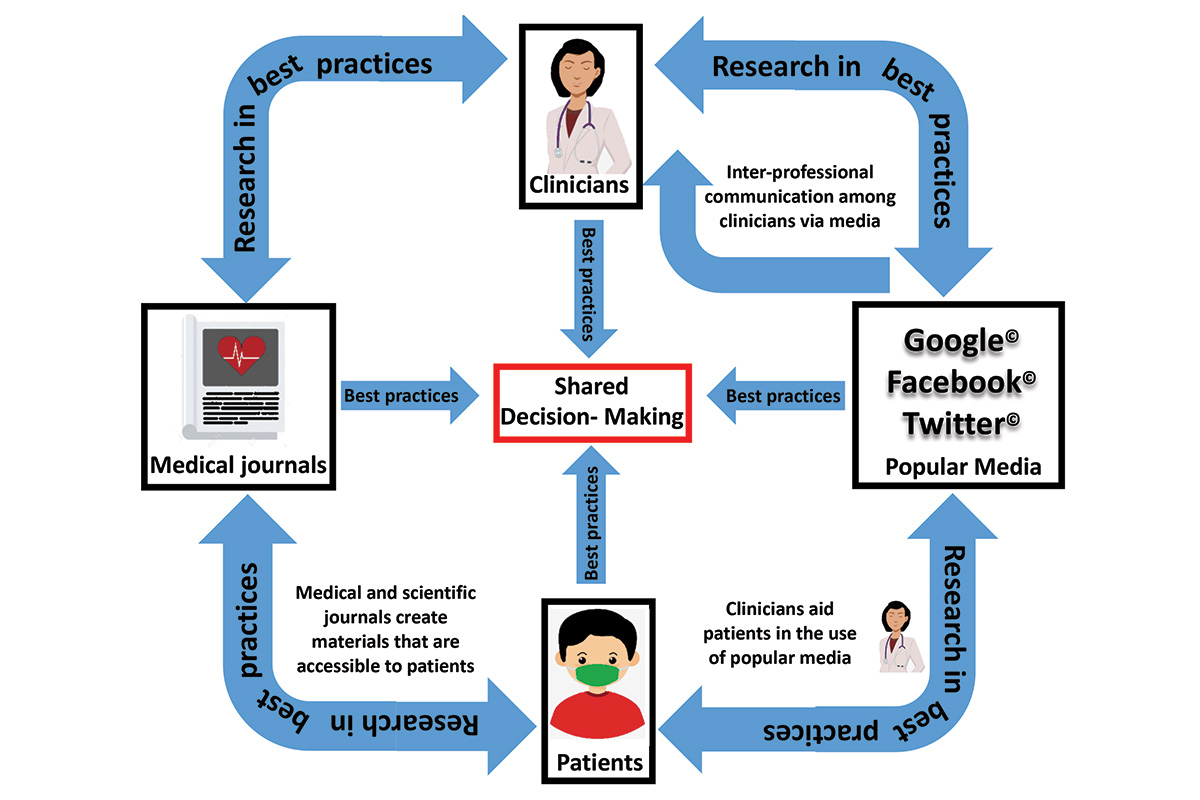

In a recent publication,8 we proposed a framework for optimizing the popular media experience, centered around four key stakeholders: 1) patients, 2) clinicians, 3) medical journals and 4) online resources (social media platforms, blogs, search engines, etc.).

Each of these feed into optimized shared decision-making between patients and physicians, warranting determining best practices for each (Figure).

Patients and Clinicians

Clinicians should engage with patients to learn more about sources they use to obtain medical information and, when appropriate, guide them towards high-quality, evidence-based resources that assist them in making decisions best suited to their needs.

Several institutions and professional societies publish patient-oriented materials online. These include ACC's CardioSmart and the American Heart Association's Health Topics.

Resources of this type are evidence-based, easily accessible and curated to a general level of health literacy. In addition to encouraging the use of these resources, the responsible use of media outlets by clinicians has tremendous potential to foster healthy professional relationships that allow for open communication and enhance shared decision-making.

Clinicians With Other Clinicians

Clinician presence on popular media is an invaluable asset for education, collaboration and career development and should be encouraged to foster personal and professional growth.

While sharing personal perspectives on social media can make clinicians seem more relatable and personable, interactions, even those that remain among clinicians, are easily viewed and judged through the public lens.

Caution ought to be exercised with regard to professionalism and patient privacy.

Medical/Scientific Journals and Professional Societies

Scientific publications are valuable sources of medical information but may be too technical for those who are not well versed in the field. We propose that medical and scientific journals take a stance against medical misinformation by publishing patient-oriented articles and infographics that are widely available and easily tailored to the knowledge level of those who may not be medically inclined.8

These may be voluntarily published by journals and made available free of charge to the public or may be published via pre-existing platforms such as the ACC's CardioSmart.

Search Engines and Social Media Platforms

Search engines and social media platforms are powerful players in the dissemination of medical information. The initial results that appear from an internet search in a search engine and topics that are frequently trending are most likely to get the greatest public attention, regardless of whether or not the information is accurate.

There is a robust role for interaction between search engines, popular media platforms, medical journals and professional organizations to participate in search engine optimization so the most credible sources of medical information are likely to have the highest visibility.

The interplay of patients, clinicians, popular media and scientific advancement is fluid and ever changing. There is therefore a need for qualitative and quantitative research to better understand interactions between the key stakeholders, differences in health information seeking behavior and what a successful sharing of medical knowledge looks like.

The use of popular and social media to assist with shared health care decision-making has been both an asset and a detriment. There is great potential for improvement to optimize and streamline the delivery of accurate and quality medical information and transform this double-edged sword into an educational tool for the dissemination of health care information.

Clinical Topics: COVID-19 Hub, Dyslipidemia, Nonstatins, Novel Agents, Statins

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, COVID-19, Pandemics, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Personal Protective Equipment, Social Media, Ethnic Groups, Vitamins, Hysteria, Emotions, American Heart Association, Decision Making, Virulence, Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors, Public Health, Goals, Patient Advocacy, Social Networking, Reproducibility of Results, Health Personnel, Cardiology, Communication, Information Seeking Behavior, Health Literacy, Midazolam, Privacy, Learning, Internet, Societies

< Back to Listings