Feature | TAVR: From Then Until Now

In a little less than a decade, we have experienced a major paradigm shift in the management of patients with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis (AS). Starting in 2011, with the first commercial approval of TAVR by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), more than 300,000 patients have been treated in the U.S.

Although it currently seems as if a tsunami is occurring, actually it has been a 31-year journey since the initial idea was conceived by Henning Andersen, MD, PhD, a cardiologist in Aarhus, Denmark.

Milestones along this journey include the first series of animal implantations that were presented as a poster at the European Society of Cardiology Congress in 1992, the first human TAVR implantation by G. Alain Cribier, MD, in Rouen, France, in 2002 and the first U.S. experience in 2004.

The Evidence

In the U.S., two series of investigational device exemption (IDE) randomized trials leading to FDA approval started in 2007. These regulatory approval trials, the PARTNER trials of the balloon-expandable Sapien Valve (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA) and the CoreValve/Evolut Trials (Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) of a self-expanding valve led to the initial FDA approval of TAVR in 2011 and reimbursement coverage by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2012.

These series of trials have enrolled a total of 9,682 patients, of which 8,098 have been randomized to TAVR with a control of either medical therapy or SAVR. This has resulted in a robust evidence base that led to hundreds of peer reviewed publications, including 10 articles in the New England Journal of Medicine and two in The Lancet.

The two series of trials started in inoperable patients, finding that TAVR was superior to medical therapy. The subsequent trials in high risk and intermediate surgical risk patients all found that TAVR was noninferior to SAVR.

The latest of the trials in patients with low surgical risk presented and published in 2019, found that TAVR was either superior to or noninferior to SAVR at one and two years.1,2 Ten year follow-up is planned for both trials.

The Now

All commercially implanted TAVR devices in the U.S., with the exception of government hospitals, are entered into the STS/ACC TVT Registry, a condition of reimbursement by a National Coverage Determination (NCD) issued by CMS.

According to registry data, there are currently 716 centers in the U.S. performing TAVR, and in 2019 there were approximately 75,000 patients treated.3

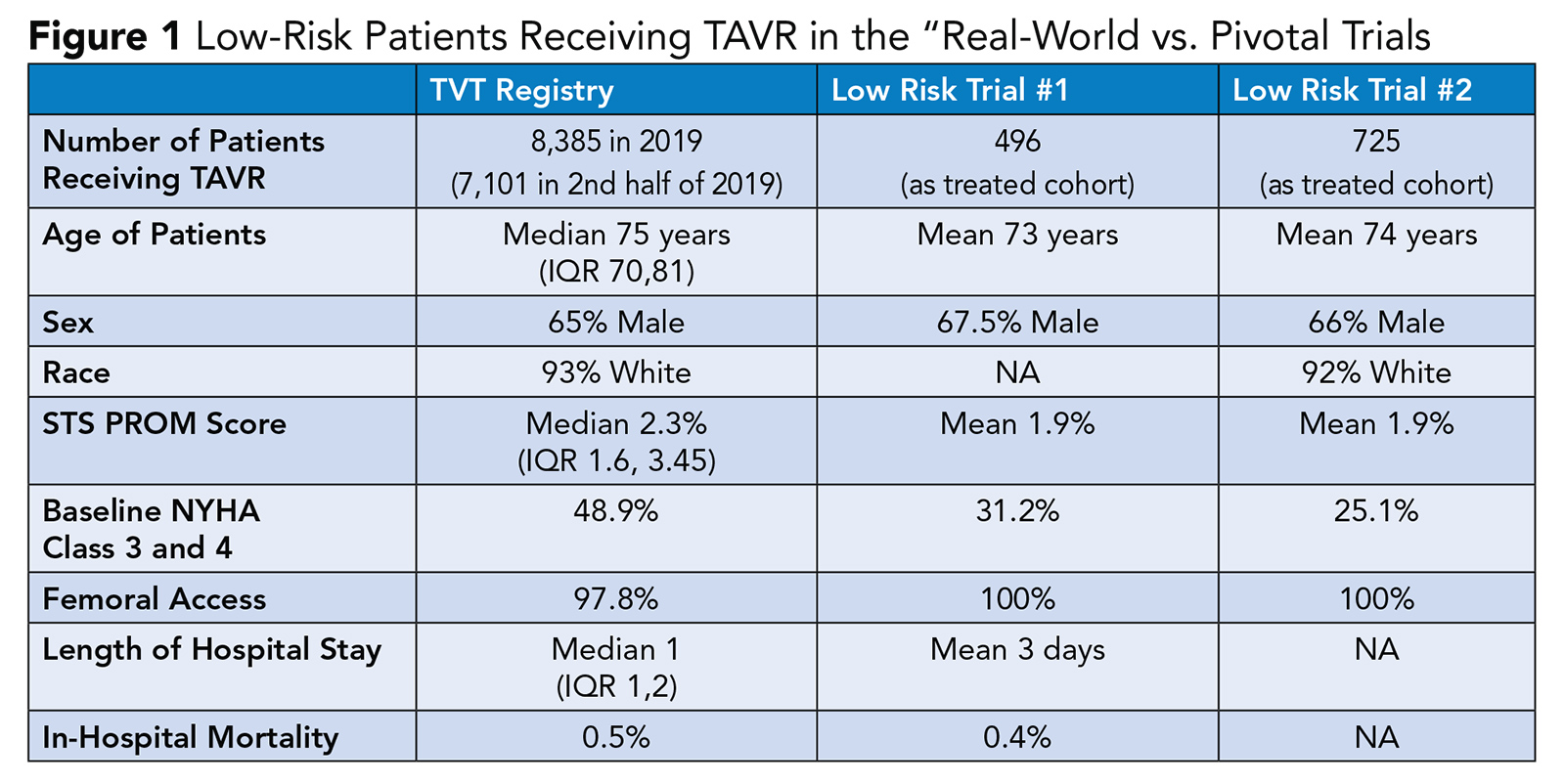

The demographics and outcomes of patients treated in the real-world setting largely mirrors those patients treated in the pivotal trials (Figure 1).

It was estimated that there would be a 20-25% further increase in TAVR implantations in 2020 resulting in a total of 90,000 to 100,000 patients undergoing the procedure. However, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has attenuated that continued procedural growth by an estimated 20%.

The Candidates

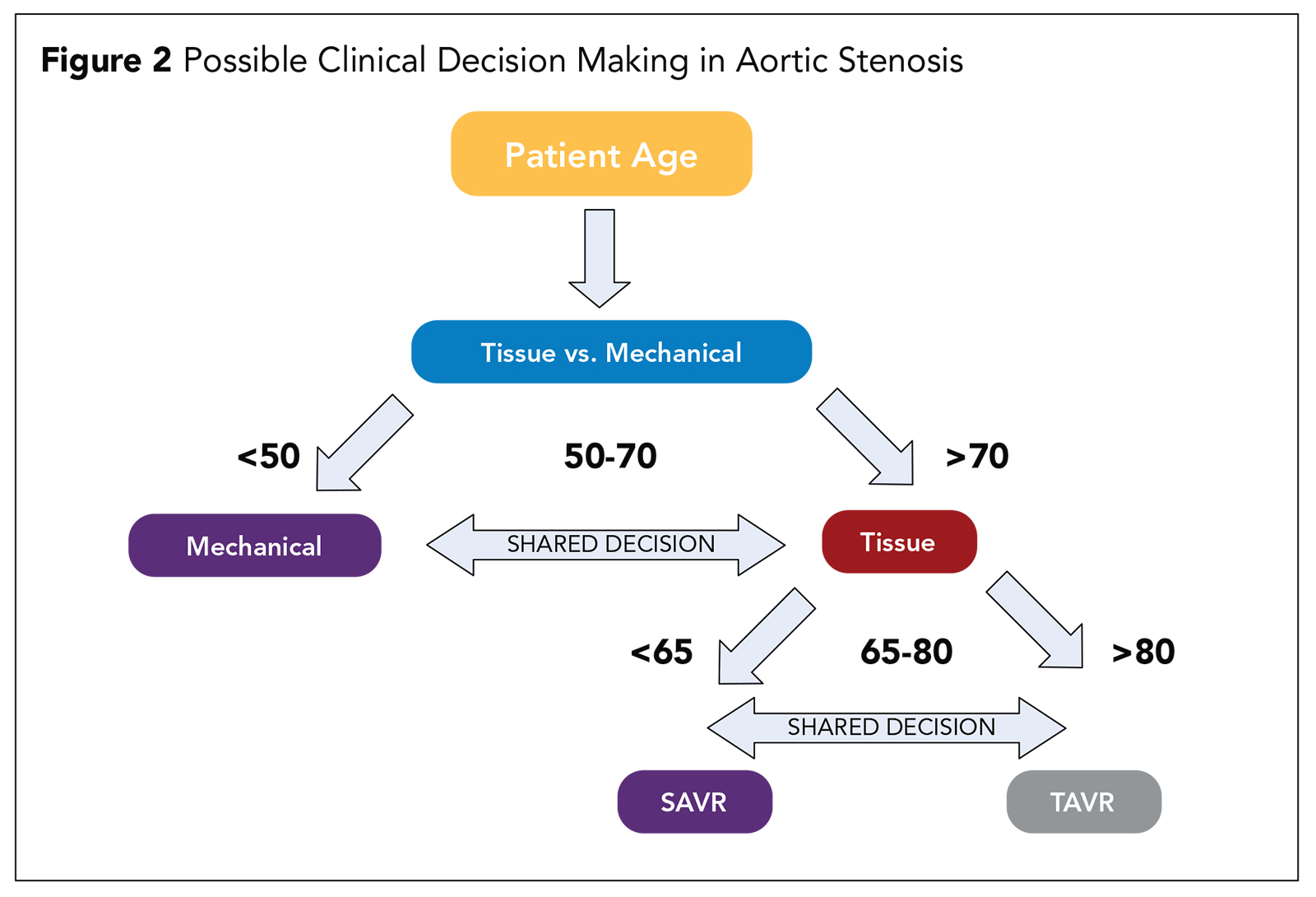

Based on trial evidence, the decision regarding appropriate candidates for TAVR should no longer be based on the patient's risk for a surgical procedure. Rather, the patient's age should be the basis for the initial decision (Figure 2).

In a possible decision pathway, the first decision is to determine whether the patient is better suited for a tissue valve or a mechanical valve. Current guidelines recommend a mechanical valve for patients <55 years and a tissue valve for patients >65 years with shared decision-making based on patient's preference being the determining factor in patients between 55 and 65 years.4

If a patient is deemed to be best suited for a tissue valve, the next decision is determining whether the patient is best treated by TAVR or SAVR. There were very few patients younger than 65 years (<10%) enrolled into any of the low risk TAVR trials, so we lack a robust body of evidence in younger patients.

Currently most patients >80 years are best treated with TAVR and those 65 years or younger by SAVR, with individual patient preferences and patient comorbidities and valve path-anatomic factors informing the decision in for patients between 65 and 80 years.

The path-anatomic factors for consideration in patients 65 and 80 years include trial exclusions such as patients with bicuspid aortic valves, extensive left ventricular outflow tract calcium, asymptomatic patients and those with complex concomitant coronary artery disease.

Therefore, SAVR should be the preferred approach in these patients who have a reasonable surgical risk. In addition, other patients who are at high risk for TAVR include those with low-lying coronary artery orifices or requiring an alternative access approach and there should be strong consideration for SAVR.

The Unanswered Questions

Other evidence gaps regarding TAVR to be addressed include the greater need for a new permanent pacemaker, which becomes more important in younger patients, and a higher incidence of new left bundle branch block which has been determined to be a risk factor for long-term mortality.

The issue of valve thrombosis and need for anticoagulation is another unanswered question. In a recent FDA-mandated CT substudy of the low-risk trials, there was imaging evidence of valve thrombus in 20-28% of patients undergoing both TAVR and SAVR by one year.5

Most of these were not associated with a clinical event and the need for anticoagulation remains unclear. A recent trial of rivaroxaban in TAVR was stopped early due to safety issues, yet a 4D CT substudy of this trial showed there was a lower incidence of valve thrombosis in the treatment arm.6,7

Durability is yet another unanswered concern. Currently, there is no significant signal of structural valve deterioration up to five years. However, very few patients are alive after five years, although some patients in the NOTION trial have been followed to eight years.

In the patients in the low-risk TAVR trials, we only have two-year follow-up data. But all these patients will be followed annually for 10 years to help answer the question of the durability of tissue valves in both TAVR and SAVR.

The use of TAVR in bicuspid aortic valves, especially in younger patients, remains an evidence gap. And it remains to be determined what evidence will be generated to indicate which patients with bicuspid aortic valves can be treated safely with TAVR and which patients should be preferentially treated with SAVR.

The Role of SAVR

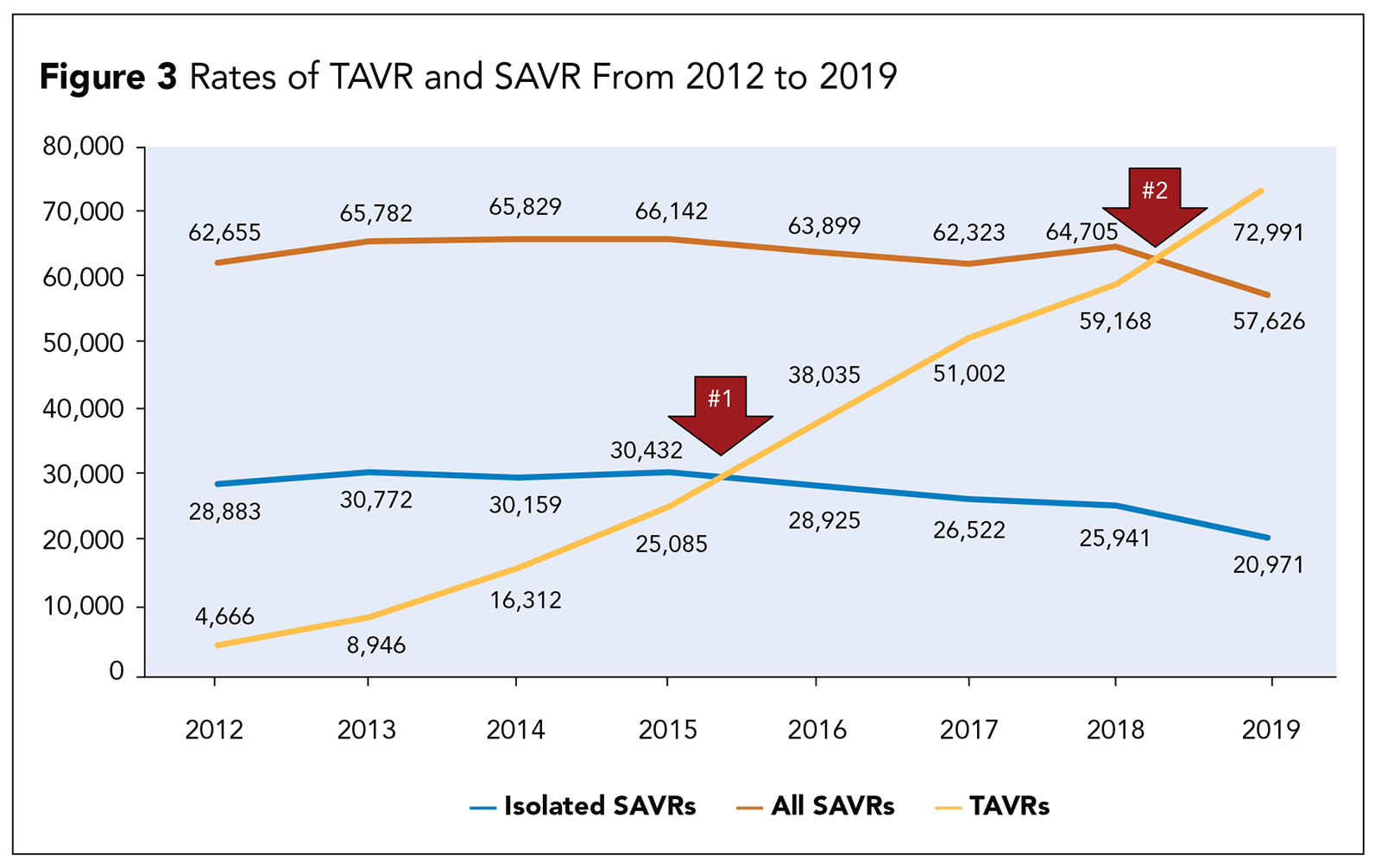

Despite the widespread adoption of TAVR, SAVR will continue be a necessary and important part of the treatment of patients with aortic stenosis (Figure 3). It is estimated that in the near future, one of three or four patients undergoing aortic valve replacement will still be best treated with SAVR.

This includes patients with extensive coronary artery disease, other valvular disease, dilation of the ascending aorta, young patients with bicuspid aortic valves and, of course, endocarditis.

The next few years will also see an increasing number of patients presenting for a surgical procedure after a previous TAVR. Early experience with surgery in these patients indicates that the complexity of the surgical procedure will be greater when explantation of a TAVR device is necessary.

Summary

In a little less than a decade, we have seen a major paradigm shift in the management of aortic stenosis. It has been truly remarkable to see the rapid adoption of a procedure that is widely applicable to a large number of patients who are able to be treated in a safe and effective manner by a broad cadre of practitioners.

Editor's Note: Click here for an editorial on patient selection for TAVR and here for recommendations for TAVR and more from the newly released ACC/AHA Guideline on Valvular Heart Disease.

References

- Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1695-1705.

- Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, et al. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1706-15.

- Carroll JD, Mack MJ, Vemulapalli S, et al J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:2492-2516.

- Otto CM, Kumbhani DJ, Alexander KP, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1313-46.

- Makkar R. PARTNER 3 Low-Risk Computed Tomography (CT) Substudy: Subclinical Leaflet Thrombosis in Transcatheter and Surgical Bioprosthetic Valves. Presented at TCT 2019, San Francisco, CA, September 2019.

- De Backer O, Dangas GD, Jilaihawi H, et al. N Engl J Med 2020;382:130-9.

- Dangas GD, Tijssen JGP, Wohrle J, et al. N Engl J Med 2019;382:120-9.

Clinical Topics: Cardiac Surgery, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Valvular Heart Disease, Aortic Surgery, Cardiac Surgery and VHD, Interventions and Structural Heart Disease

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement, Aortic Valve, Aortic Valve Stenosis, Heart Valve Prosthesis, Risk, Cardiology, Reference Standards

< Back to Listings