Cover Story | Chest Pain Evaluation, Diagnosis at Heart of New AHA/ACC Guideline

The first-ever clinical guideline from the ACC and American Heart Association (AHA) to focus solely on the evaluation and diagnosis of adult patients with chest pain provides recommendations and algorithms for conducting initial assessments, general considerations for cardiac testing, choosing the right pathway for patients with acute chest pain, and evaluating patients with stable chest pain.

The 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain offers "an evidence-based approach to risk stratification and the diagnostic workup for the evaluation of chest pain," while also incorporating cost-value considerations in diagnostic testing and shared decision-making with patients.

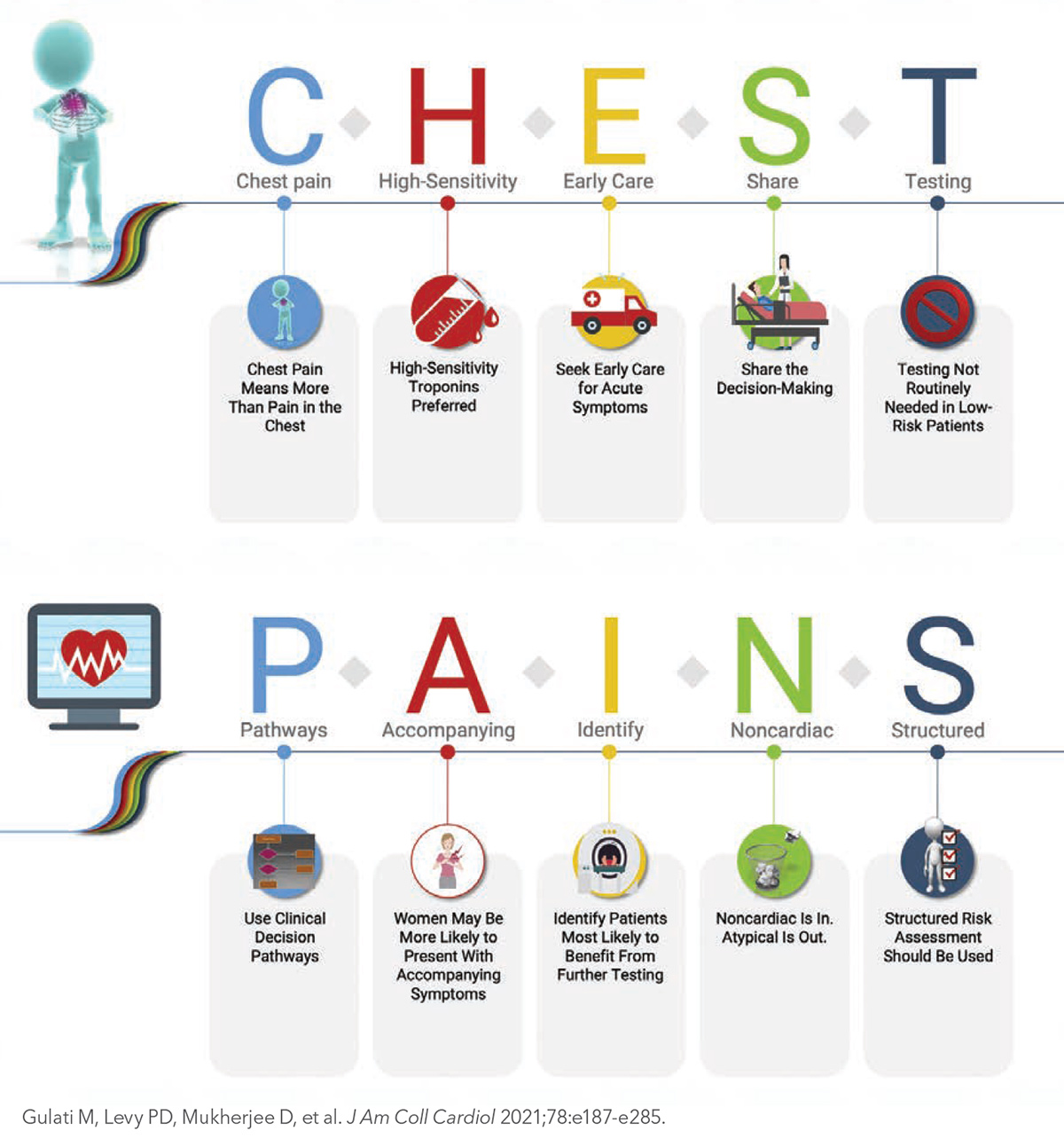

Key highlights from the guideline include a focus on signs and symptoms (including accompanying symptoms like nausea and shortness of breath in women) and the importance of early care for acute symptoms. "Chest pain means more than chest pain," is one of the top takeaways outlined in the Executive Summary, along with calling 9-1-1 immediately.

"This standard approach provides clinicians with the guidance to better evaluate patients with chest pain, identify patients who may be having a cardiac emergency and then select the right test or treatment for the right patient," said Writing Committee Chair Martha Gulati, MD, MS, FACC.

The use of high-sensitivity cardiac troponins is recommended as the preferred standard for establishing a biomarker diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction, allowing for more accurate detection and exclusion of myocardial injury. Additionally, urgent diagnostic testing for suspected coronary artery disease is not needed in low-risk patients with acute or stable chest pain, according to the guideline. The authors, including Gulati and Vice Chairs Phillip D. Levy, MD, MPH, FACC, and Debabrata Mukherjee, MD, MS, FACC, note that "patients with acute or stable chest pain who are at intermediate risk or intermediate to high pre-test risk of obstructive coronary artery disease, respectively, will benefit the most from cardiac imaging and testing."

"While there is no one 'best test' for every patient, the guideline emphasizes the tests that may be most appropriate, depending on the individual situation, and which ones won't provide additional information; therefore, these tests should not be done just for the sake of doing them," said Gulati. "Appropriate testing is also dependent upon the technology and screening devices that are available at the hospital or health care center where the patient is receiving care. All imaging modalities highlighted in the guideline have an important role in the assessment of chest pain to help determine the underlying cause, with the goal of preventing a serious cardiac event."

Notably, the use of "noncardiac" as a descriptor of chest pain is encouraged in place of "atypical," which the authors say is misleading. Other recommendations include leveraging routine use of clinical decision pathways for chest pain in the emergency department and outpatient settings, as well as the use of structured risk assessment using evidence-based protocols for patients presenting with acute or stable chest pain, or in those patients at risk for coronary artery disease or adverse events.

Looking ahead, the authors recognize that "the diagnosis and management of chest pain will remain a fertile area of investigation." As such, they highlight the need for further research and new approaches for reducing delays from chest pain symptom onset to presentation, as well as the need for continued research and best practices for reducing the differences in treatment and outcomes by sex, gender and race.

The guideline authors also highlight the important role that registries will play as platforms within which to conduct randomized trials and note the need to evaluate the impact of accreditation activities coupled with registry participation on clinical outcomes and process improvement.

The AHA/ACC Chest Pain Guideline was approved by the American Society of Echocardiography, American College of Chest Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. The writing group included representatives from each of the partnering organizations and experts in the field – cardiac intensivists, cardiac interventionalists, cardiac surgeons, cardiologists, emergency physicians and epidemiologists – and a lay/patient representative. The clinical document was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Help at the Point of Care: JACC Chest Pain Interactive Tool

The JACC Chest Pain Interactive Tool assists clinicians to determine the level of risk and appropriate subsequent testing in patients presenting with chest pain by quickly walking through multiple scenarios based on recommendations from the newly released AHA/ACC 2021 Chest Pain Guideline. The web-based tool easily connects clinicians to the recommendations, tables and figures from the new guideline and outlines the path forward for low- to high-risk patients with acute and stable chest pain.

Chest Pain Guideline Hub: Resources For Implementing the Guideline

Visit the Chest Pain Guideline Hub on ACC.org for the complete guideline, executive summary and slide set, and resources including the Guidelines Made Simple tool, Pocket Guide and Flipbook. Click here to visit and bookmark the Hub. ACC's updated Guideline Clinical App puts all the guidelines at your fingertips, in a condensed, interactive format on a mobile platform, along with risk scores, calculators and algorithms. Download it from the Chest Pain Guideline Hub.

Want to search within guidelines?

Try out the new search tool at ACC.org/Guidelines, created as a complement to the ACC/AHA Guidelines Optimization effort.

Key Perspectives: 2021 AHA/ACC Chest Pain Guideline

By David S. Bach, MD, FACC

Chest pain is one of the most common reasons that people seek medical care. This guideline was developed for the evaluation of acute or stable chest pain in outpatient and emergency department settings, emphasizing the diagnosis of chest pain with an ischemic etiology.

- Acute chest pain refers to symptoms of new onset or change in pattern, intensity or duration; stable chest pain refers to symptoms that are chronic and associated with consistent precipitants. Although the term "chest pain" is used in clinical practice, patients often report pressure, tightness, squeezing, heaviness or burning in locations in addition to the chest, including the shoulder, arm, neck, upper abdomen or jaw. Chest pain should be described as cardiac, possibly cardiac or noncardiac, rather than as typical or atypical.

- Chest pain is the most common symptom among both men and women diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). However, women more commonly have accompanying symptoms including nausea, palpitations and shortness of breath.

- Efforts should be made to expedite the evaluation of patients with acute chest pain, including patient education to call 9-1-1 for emergency medical services transportation to the nearest emergency department.

- Electrocardiography (ECG) is important in the evaluation of both acute and stable chest pain to assess for evidence of ACS.

- Owing to high sensitivity and specificity for myocardial tissue, serial assessment of cardiac troponin (cTn) I or T is the preferred biomarker for the assessment of myocardial injury among patients with acute chest pain; high-sensitivity cTn is preferred because it allows rapid detection of myocardial injury and has increased diagnostic accuracy.

- Among patients with acute or with stable chest pain, the use of diagnostic testing should be based on a structured assessment of cardiac risk and targeted to patients most likely to benefit. Clinical decision pathways (CDPs) should be used routinely in the emergency department and in outpatient settings.

- Clinically stable patients evaluated for chest pain should be included in clinical decision-making, weighing information about costs, risks of adverse events, radiation exposure and alternative options.

- CDPs for patients with acute chest pain:

- Among patients with acute chest pain and low cardiovascular risk (30-day risk of death or major adverse cardiac events [MACE] <1%), no additional urgent cardiac testing may be needed.

- Among patients with acute chest pain at intermediate risk (patients without high-risk features and not classified as low risk) and no known coronary artery disease (CAD), additional testing can include functional testing (exercise ECG, stress echocardiography, stress nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging [MPI], or stress cardiac magnetic resonance [CMR] imaging) or anatomic testing (coronary computed tomography angiography [CCTA]).

- Among patients with known CAD and acute chest pain at intermediate risk, additional testing can include functional testing or CCTA in the setting of nonobstructive CAD; functional testing in the setting of known obstructive CAD; or invasive coronary angiography (ICA) in the setting of known left main disease, proximal vessel CAD or multivessel CAD.

- Patients with acute chest pain and high risk (new ischemic changes on ECG, cTn-confirmed myocardial injury, new left ventricular systolic dysfunction, new moderate-severe ischemia on functional testing, hemodynamic instability, or a high-risk CDP score) should undergo ICA.

- Nonischemic cardiac causes of acute chest pain include acute aortic syndrome (evaluable with CTA), acute pulmonary embolus (PE; evaluable with PE-protocol CTA), myopericarditis (evaluable with CMR) and valve disease (evaluable with echocardiography).

- CDPs for patients with stable chest pain:

- Among patients with stable chest pain and no known CAD, patients at low probability of obstructive CAD and a favorable prognosis can be identified using a pretest probability model that incorporates age, sex and presenting symptoms; among these patients, additional diagnostic testing can be deferred. Coronary artery calcium testing can be used as a first-line test to exclude calcific plaque.

- Among patients at intermediate-high risk with stable chest pain and no known CAD, CCTA is useful for the diagnosis of CAD and for risk stratification; and stress imaging (echocardiography, MPI or CMR) is useful for the diagnosis of ischemia and for estimating the risk of MACE.

- Among patients with known obstructive CAD and stable chest pain despite guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), stress imaging (MPI, CMR or echocardiography) is recommended for the diagnosis of ischemia and assessment of risk. Patients at high risk or those with moderate-severe ischemia should undergo ICA.

- Among patients with known nonobstructive CAD and stable chest pain despite GDMT, CCTA or stress testing is reasonable.

- Among patients with documented nonobstructive CAD, persistent stable symptoms, and imaging-documented myocardial ischemia, it is reasonable to assess for microvascular dysfunction and enhance risk stratification using invasive coronary function testing, stress positron emission tomography with assessment of myocardial blood flow reserve (MBFR), or stress CMR with assessment of MBFR.

- Layered testing (when one test is followed by more tests) leads to higher costs; cost-value considerations suggest that the clinician should select the test most likely to answer the clinical question.

Clinical Topics: Acute Coronary Syndromes, Cardiovascular Care Team, Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Noninvasive Imaging, Prevention, Atherosclerotic Disease (CAD/PAD), ACS and Cardiac Biomarkers, Statins, Heart Failure and Cardiac Biomarkers, Interventions and ACS, Interventions and Coronary Artery Disease, Interventions and Imaging, Angiography, Computed Tomography, Echocardiography/Ultrasound, Nuclear Imaging, Exercise

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Abdomen, Accreditation, Acute Coronary Syndrome, Algorithms, American Heart Association, Antineoplastic Combined Chemotherapy Protocols, Arm, Biomarkers, Pharmacological, Calcium, Cardiologists, Cardiology, Cardiovascular Diseases, Chest Pain, Cisplatin, Clinical Decision-Making, Computed Tomography Angiography, Coronary Angiography, Coronary Artery Disease, Coronary Vessels, Cytidine Diphosphate, Decision Making, Shared, Delivery of Health Care, Diagnostic Techniques and Procedures, Dyspnea, Echocardiography, Echocardiography, Stress, Electrocardiography, Embolism, Emergency Medical Services, Emergency Medicine, Emergency Service, Hospital, Epidemiologists, Etoposide, Goals, Heart Disease Risk Factors, Hemodynamics, Hospitals, Internet, Ischemia, Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy, Myocardial Infarction, Myocardial Ischemia, Myocardial Perfusion Imaging, Nausea, Outpatients, Patient Advocacy, Patient-Centered Care, Point-of-Care Systems, Positron-Emission Tomography, Prognosis, Radiation Exposure, Reference Standards, Registries, Risk Assessment, Risk Factors, Shoulder, Surgeons, Technology, Treatment Outcome, Troponin, Walking, Writing