Cover Story | Pulmonary Embolism: A Clinical Approach

Pulmonary embolism (PE) continues to challenge clinicians with its complex presentation and potential for rapid deterioration. As the third leading cause of cardiovascular mortality in the U.S. –following only myocardial infarction and stroke – PE claims more than 40,000 lives annually and accounts for about 40% of the more than 1 million hospitalizations for venous thromboembolism in the country.1

Despite significant advances in prevention, diagnosis and treatment, this condition continues to present clinicians with complex decisions that demand rapid, precise judgment. Successful management requires a nuanced approach that begins with precise risk assessment and diagnostic accuracy, both areas in which cardiologists excel.

"Pulmonary embolism is a cardiovascular disease and we as cardiovascular specialists are ideally positioned to help manage these patients in the acute and even the chronic phase," notes Geoffrey D. Barnes, MD, MSc, FACC, in an interview with Cardiology. Barnes is a cardiologist and vascular medicine specialist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

"We are experts in cardiac biomarkers and echocardiographic imaging, which are used in diagnosis and risk stratification; we know how to prescribe and monitor anticoagulation; we have expertise in the cath lab and are the ones to manage critically ill patients with right ventricular (RV) dysfunction," he adds. "We also know how to manage patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and we know how to manage patients in the chronic setting who have dyspnea and often have limited functional capacity. We're really the specialty best prepared to manage most of the areas related to acute and chronic pulmonary embolism."

International Clinical Practice Guidelines

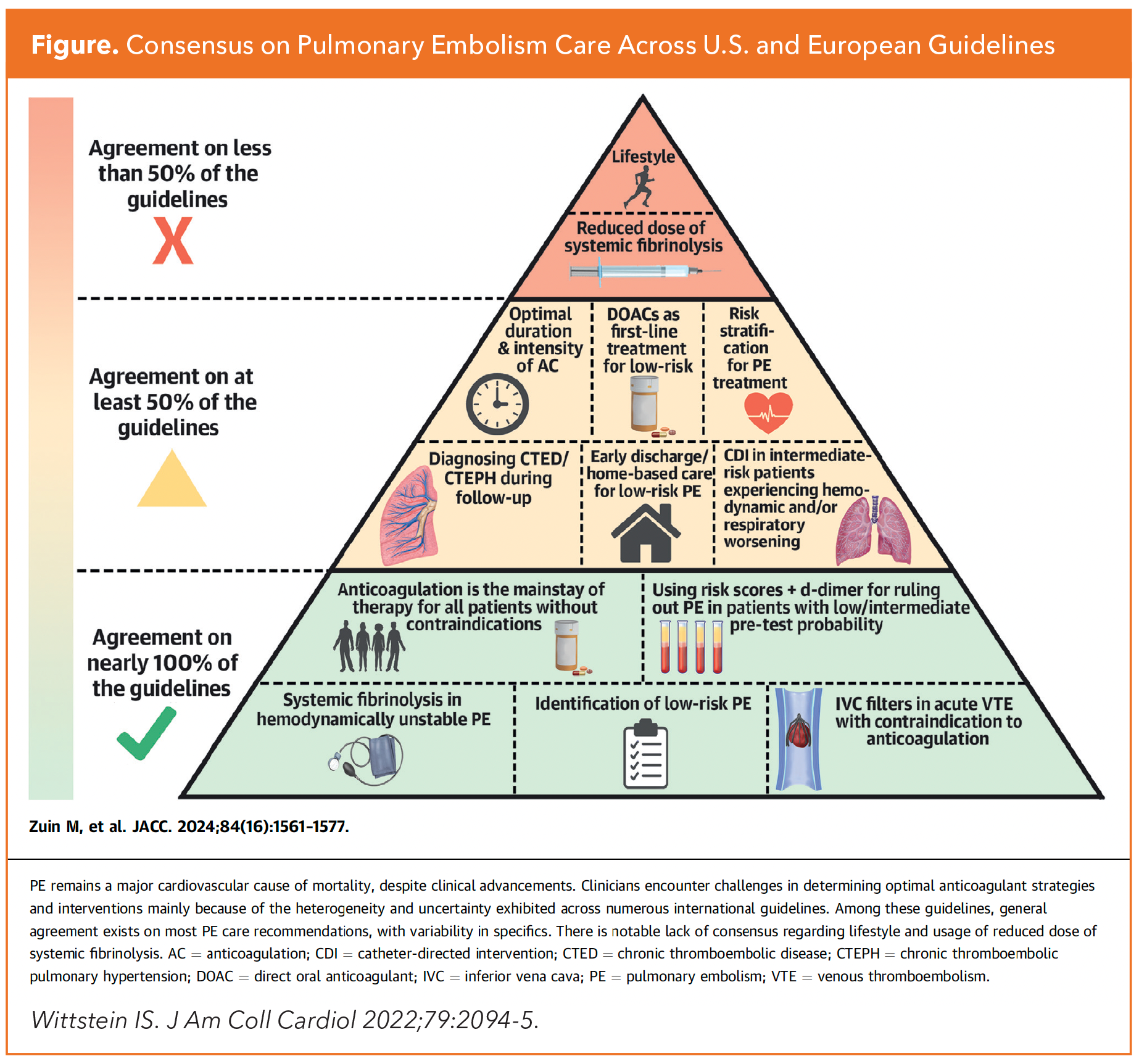

Current guidelines for PE management include those issued by the American Society of Hematology (ASH, 2018), the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST, 2021), and the European Society of Cardiology in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ESC/ERS, 2019).2-4 There is also a consensus practice statement from the Pulmonary Embolism Response Team (PERT) from 2019 and a scientific statement from the American Heart Association from 2011.5,6

The most recent efforts, both released in 2023, include a clinical guideline on diagnosis and management of venous thromboembolic diseases and a "consultation document" on percutaneous thrombectomy for massive PE from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellent, the UK's public health body that provides national guidance and advice to improve health and social care.7,8

A review comparing these guidance documents highlighting areas of consistency, divergence and gaps was published in JACC last fall by Marco Zuin, MD, MS, Gregory Piazza, MD, MS, FACC, and colleagues (Figure).9

Early Diagnosis and Risk Stratification: Cornerstones of PE Management

"The first step in the diagnosis of PE is to use a validated tool to determine pretest probability. The degree of pretest probability will inform the decision of whether to order a D-dimer, which will either exclude the diagnosis of PE or prompt immediate imaging," says Piazza, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, MA.

Early detection and diagnosis of PE starts with an initial patient assessment using validated tools (e.g., Wells Score, Geneva Score) to assess pretest probability, followed by D-dimer testing. In those with a low pretest probability, a negative D-dimer result excludes the diagnosis of PE, whereas a positive test or a high initial pretest probability requires imaging confirmation.

Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) is the primary diagnostic tool for acute PE across most guidelines. V/Q scanning is preferred in the ASH guideline in cases where CTPA is contraindicated or unavailable, and bedside echocardiography is suggested in hemodynamically unstable patients if CTPA is not feasible.

After a definitive diagnosis is made, validated risk stratification tools (mostly the pulmonary embolism severity index [PESI] or its simplified version [sPESI]) help categorize patients as low, intermediate or high risk.

"Once a diagnosis is made, the next important step is to consider the use of a Pulmonary Embolism Response Team, or PERT, to help guide early management decisions, facilitate access to advanced intervention, if that's necessary, and to make sure the patient has the right follow-up," says Piazza.

PERT teams bring together experts from multiple specialties, including pulmonary/critical care, cardiology, vascular medicine, interventional radiology, emergency medicine and cardiac surgery. They use a collaborative approach to quickly assess and develop treatment plans for PE patients, functioning similarly to other rapid response teams like stroke or STEMI teams, providing 24/7 availability for PE cases. The first PERT was established at Massachusetts General Hospital in 2012, and the concept has since spread widely, leading to the creation of the PERT Consortium in 2015.

For those identified as low-risk PE, PERT care is likely not needed. Risk stratification can help with, among other things, selecting the location of care (home, general medical wards, intermediate care unit or intensive care unit).

While effective PE management hinges on accurate risk assessment, which guides therapeutic decisions and predicts patient outcomes, these commonly used risk tools for acute PE have only modest estimating ability, notes Barnes. Also, as patients evolve clinically, risk profiles can change, necessitating reassessment and possibly an adjustment of therapeutic approach.10

In a recent validation study conducted by Barnes and colleagues of four commonly used risk stratification scores (ESC, PESI, sPESI and Bova), the researchers found only modest capabilities to predict seven-day and 30-day mortality.11

Says Barnes, "We have several risk stratification tools, and they are clinically and statistically significant, but they don't do a great job putting patients into buckets that clearly define who needs specific therapies. We haven't figured out how to combine all the different risk elements together to make a really clear schema that will guide clinicians."

At present, the ESC risk tool, which recommends using PESI or sPESI but also adds biomarker and radiological markers to the scheme, is probably the most advanced tool available, he says.

Treatment Strategies: A Tiered Approach

Anticoagulation is the cornerstone of PE treatment for all risk levels. In fact, in patients with suspected PE, there is consensus to start empiric therapeutic anticoagulation while awaiting diagnostic results if the pretest probability of PE is intermediate or high and bleeding risk is low.

Low-Risk PE: About 60% of patients identified as having acute PE are considered low risk and do not require hospital admission.10 Those who are more symptomatic or have higher PESI scores may benefit from inpatient treatment initiation and observation.

For hemodynamically stable patients with no RV strain and normal cardiac biomarkers, anticoagulation becomes the primary focus. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have high-quality evidence supporting their use in low-risk PE and have transformed treatment protocols, offering clinicians a convenient and predictable management strategy that is noninferior in efficacy compared to vitamin K antagonists but associated with lower bleeding risk. There have been very few head-to-head comparisons of DOACs in this setting, so choice of agent can be guided by other factors, including pharmacologic properties, patient characteristics and patient preferences.12

Intermediate-Risk Scenarios: About 30% of acute PE is classified as intermediate risk, with mortality ranging from 2% for those with only biomarker abnormalities to 10% for those with both RV dilation and biomarker abnormalities.10

For individuals classified as intermediate-low risk, those with RV dysfunction or biomarker elevation (but not both), standard anticoagulation is often first-time treatment. But for the 5% to 10% who have intermediate-high-risk PE, characterized by both RV dysfunction and biomarker elevation, progression to hemodynamic instability is a real possibility and treatment beyond anticoagulation should be considered, guided by the presence of myocardial strain or hypotension.

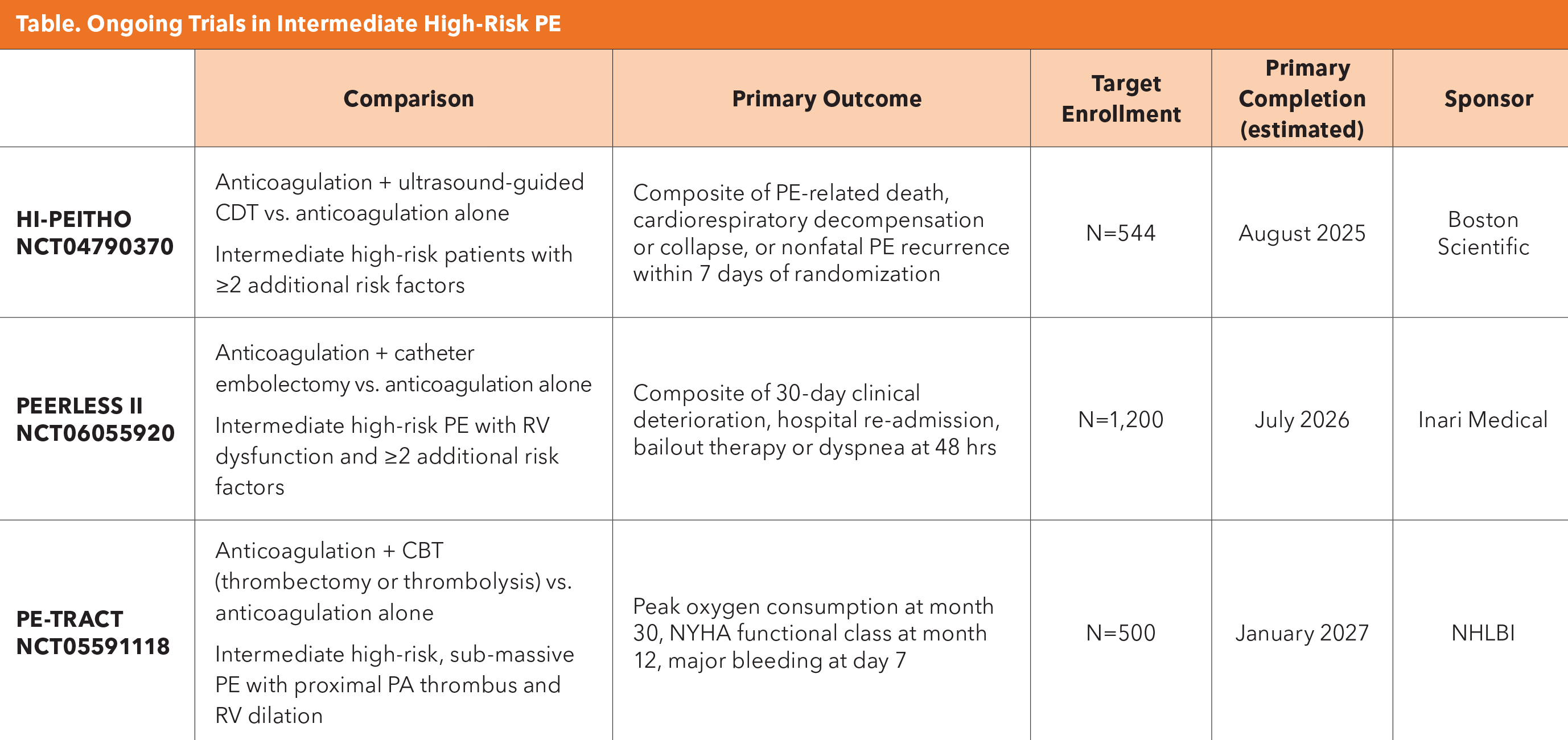

"The intermediate high-risk group is challenging because of our limited ability to predict progression and the current lack of clarity in terms of who might benefit from reperfusion therapy, whether that be catheter embolectomy, catheter thrombolysis, which uses a lower dose thrombolytic, or surgical embolectomy," says Piazza. Indeed, this is an active area of investigation (see sidebar).

High-Risk PE: About 5% of patients present with high-risk PE.12 There is some heterogeneity in international guidelines with respect to the identification of high-risk PE although most suggest this subgroup should be defined as sustained hypotension (systolic blood pressure [SBP] <90 mm Hg or a decrease in SBP ≥40 mm Hg from baseline or need for vasopressor support).

In terms of nomenclature, this category used to be referred to as high-risk of massive PE, but the term massive is no longer in favor. Some groups in Europe, notes Piazza, use the word "catastrophic" instead. "Massive implies a judgement on the anatomical size of the pulmonary embolism, which doesn't necessarily relate to outcomes. The term should not be used," says Piazza.

Aggressive intervention becomes imperative in high-risk scenarios and this treatment may encompass systemic thrombolysis, surgical embolectomy, and in select cases, even ECMO. These interventions demand rapid decision-making and a multidisciplinary approach to patient management.

Pharmacologic thrombolysis takes center stage in high-risk cases, with alteplase (tPA) considered the standard intervention, typically administered as a 100 mg infusion over two hours.

Clinicians should remain vigilant about absolute contraindications, including active internal bleeding, recent intracranial procedures, uncontrolled hypertension and recent hemorrhagic events. These considerations are paramount in preventing potentially catastrophic complications.

Advancing Our Practice

"Pulmonary embolism demands a nuanced, patient-specific approach that challenges even the most experienced clinicians. Cardiovascular specialists are well-positioned to provide the individualized management, robust risk stratification, strategic anticoagulation selection, judicious use of thrombolytics and vigilant monitoring upon which success hinges," says Barnes.

"As the field continues to advance, with emerging catheter-based technologies, I hope we'll see cardiologists, both in the community and hospital-based, taking a more active role in managing these patients."

PERT Outcomes Data

Despite advances in technology and the implementation of PERTs, standardized management practices and detailed outcomes data for these high-risk patients have been lacking. Kobayashi, et al., recently reported on the largest cohort of high-risk PE patients to date, using data from the PERT Consortium Registry, comprising 35 PERT centers in the U.S.1

A total of 5,790 patients with intermediate- or high-risk PE treated between October 2015 and April 2022 were included in the retrospective cohort study. Of them, 1,442 were classified as high-risk PE (defined as sustained SBP <90 mm Hg, need for vasopressors or cardiac arrest), including 197 catastrophic cases (high-risk patients in hemodynamic collapse). Outcomes were compared to those seen in a reference group of intermediate-risk PE patients.

Findings showed that advanced therapies, including systemic thrombolysis, catheter-directed thrombolysis, catheter-based and surgical embolectomy, and ECMO, were used in 41.9% of high-risk patients and in 30.2% of intermediate-risk patients (p<0.001). Compared to intermediate-risk patients, high-risk patients were more likely to receive mechanical circulatory support with ECMO (6.3% vs. 0.4%; p<0.001), surgical embolectomy (2.8% vs. 1.3%; p<0.001) and systemic thrombolysis (13.1% vs. 2.8%; p<0.001).

In-hospital mortality, the primary outcome, was seen in 3.7% of intermediate-risk PE patients, jumping to 20.6% for those deemed to have high-risk PE (p<0.001) and to 42.1% for those with catastrophic PE (p<0.05). Major bleeding rates were 3.5%, 10.5% and 23.3%, respectively (p<0.001 for all).

Predictors of mortality included vasopressor use (odds ratio [OR], 4.56; p<0.01), ECMO use (OR, 2.86; p=0.03), identified clot-in-transit (OR, 2.26; p=0.02), malignancy (OR, 1.70; p=0.01) and hypoxia (OR, 1.50; p=0.02).

Catastrophic PE patients had higher in-hospital mortality (42.1% vs. 17.2%; p<0.001) than those presenting with non-catastrophic high-risk PE. Catastrophic PE patients were also more likely to receive ECMO (13.3% vs. 4.8%; p<0.001) and systemic thrombolysis (25.0% vs. 11.3%; p<0.001) compared to non-catastrophic high-risk PE.

The authors conclude: "Disappointingly, our data continue to show significant mortality in patients experiencing high-risk PE despite technological advancements in catheter-based and surgical strategies as well as the larger national implementation of PERT teams." The extremely high mortality seen in the high-risk PE group with hemodynamic collapse (nearly six-fold that seen in the intermediate-risk cohort) is consistent with previous reports.

- Kobayashi T, Pugliese S, Sethi SS, et al. Contemporary Management and Outcomes of Patients with High-Risk Pulmonary Embolism. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024;83:35-43.

Emerging Frontiers: Catheter-Based Therapies

The catheter-based therapy landscape for acute PE treatment continues to evolve dynamically. Concentrated primarily in specialized PERT centers, these innovative approaches offer tantalizing possibilities for targeted clot removal and reduced systemic thrombolytic exposure. Ongoing clinical trials promise to illuminate the full potential of these emerging technologies.

The study enrolled 550 intermediate-risk PE patients with RV dilatation and additional clinical risk factors.1 No significant differences in mortality, intracranial hemorrhage or major bleeding were observed between the two groups.

The primary outcome was a five-component hierarchical win ratio of all-cause mortality, intracranial hemorrhage, major bleeding, clinical deterioration/escalation to bailout therapy, and ICU admission and ICU length-of-stay during the index hospitalization and following the index procedure.

Researchers found this outcome occurred significantly less frequently with LBMT vs. CDT (win ratio, 5.01; p<0.001). With LBMT there were also significantly fewer episodes of clinical deterioration and/or bailout (1.8% vs. 5.4%; p=0.04) and less postprocedural ICU utilization (p<0.001).

The study enrolled 550 intermediate-risk PE patients with RV dilatation and additional clinical risk factors.1 No significant differences in mortality, intracranial hemorrhage or major bleeding were observed between the two groups.

"The PEERLESS study provides the first randomized data for mechanical thrombectomy and important new information to inform endovascular treatment selection for intermediate-risk PE patients in whom the decision to intervene has been made by the patient's care team," wrote principal investigator Wissam A. Jaber, MD, FACC, and colleagues.

Says Barnes, "PEERLESS taught us a lot about how to select between catheter-based embolectomy and CDT, but it did not teach us about selecting who needs an interventional therapy vs. who should just receive anticoagulation."

That question is being addressed in three ongoing trials: HI-PEITHO, PEERLESS 2 and PE-TRACT. "PE-TRACT, specifically, is an important trial because it is government funded and, essentially, device agnostic," says Barnes.

The PE-TRACT trial is evaluating how any device approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration compares to anticoagulation, and is "primarily looking at functional, patient-centered outcomes – peak oxygen consumption, walk distance, NYHA functional class, etc." Participants will receive mechanical thrombectomy or CDT; the exact technique and devices used is at the discretion of the endovascular physician, within parameters defined by the PE-TRACT Manual of Operations and accepted standard care.

CBT, catheter-based therapy; CDT, catheter-directed thrombolysis; RV, right ventricle; PA, pulmonary artery.

While CDT promises reduced exposure to systemic thrombolytic therapies and potential for targeted clot removal, there are limited long-term outcome data. For now, CDT is primarily implemented in specialized PERT centers and is considered an emerging technology with promise rather than an established technology.

- Jaber WA, Gonsalves CF, Stortecky S, et al. Large-Bore Mechanical Thrombectomy Versus Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis in The Management Of Intermediate-Risk Pulmonary Embolism: Primary Results of the PEERLESS Randomized Controlled Trial. Circulation. 2024;Oct. 29: doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.124.072364.

This article was authored by Debra L. Beck, MSc.

References

- Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. 2024 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149:e347-e913.

- Ortel TL, Neumann I, Ageno W, et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 Guidelines for Management of Venous Thromboembolism: Treatment of Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. Blood Adv. 2020;4:4693-4738.

- Stevens SM, Woller SC, Baumann Kreuziger L, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: Compendium and Review of CHEST Guidelines 2012-2021. Chest. 2024;166:388-404.

- Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism Developed in Collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J. 2020;41:543-603.

- Rivera-Lebron B, McDaniel M, Ahrar K, et al. Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow Up of Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Consensus Practice from the PERT Consortium. Clin Appl Thromb Off J Int Acad Clin Appl Thromb. 2019;25:1076029619853037.

- Jaff MR, McMurtry MS, Archer SL, et al. Management of Massive and Submassive Pulmonary Embolism, Iliofemoral Deep Vein Thrombosis, and Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:1788-1830.

- Venous Thromboembolic Diseases: Diagnosis, Management and Thrombophilia Testing. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2023. Accessed Jan. 9, 2025. Available here.

- Percutaneous Thrombectomy for Intermediate-Risk or High-Risk Pulmonary Embolism. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Accessed Jan. 9, 2025. Available here.

- Zuin M, Bikdeli B, Ballard-Hernandez J, et al. International Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations for Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Harmony, Dissonance, and Silence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;84:1561-1577.

- Faggioni M, Giri J, Glassmoyer L, Kobayashi T. A Rational Approach to the Treatment of Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Annu Rev Med. 2025;Jan 2:10.1146/annurev-med-050423-085457.

- Barnes GD, Muzikansky A, Cameron S, et al. Comparison of 4 Acute Pulmonary Embolism Mortality Risk Scores in Patients Evaluated by Pulmonary Embolism Response Teams. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2010779.

- Kahn SR, de Wit K. Pulmonary Embolism. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:45-57.

Clinical Topics: Vascular Medicine

Keywords: Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications, Myocardial Infarction, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, Pulmonary Embolism