From the Member Sections | Tackling the Polypharmacy Pandemic in CV Care

In recent years, numerous health care challenges have been tackled, some making headlines, while others quietly escalate under the radar – like polypharmacy. Cardiovascular medications frequently lead this category, often contributing to adverse clinical outcomes, including emergency department visits and hospitalizations. As clinicians, we're caught between evidence-based guidelines and the need for individualized care, a balance that's even more delicate with older adults. The most vulnerable among us are often prescribed the most complex regimens, creating the perfect storm for preventable harm.

In today's health care landscape, where quality metrics tied to reimbursement have become the standard, clinicians are under increasing pressure to prescribe specific medications. The good news is that these metrics are evolving to better meet the unique needs of older, frail patients. Initiatives such as the World Health Organization's "Medication Without Harm" and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' (CMS) expanded quality measures aim to reduce preventable emergency visits and hospital admissions due to medication-related harm. CMS alone has introduced over 30 medication-related metrics, with more on the horizon – underscoring the urgency for clinicians to adapt and prioritize safe, patient-centered prescribing practices now rather than later.

Polypharmacy, or the use of multiple medications, poses significant risks in elderly patients, especially with cardiovascular medications. These risks include an increased incidence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), drug-drug interactions, cognitive decline and falls, poor medication adherence, prescribing cascades and exacerbation of comorbidities.

Clinicians working with older patients have witnessed firsthand how polypharmacy can complicate both their care and diminish quality of life. In a retrospective study of older patients (≥65 years) with cardiovascular disease who were admitted to a cardiology service, the prevalence of polypharmacy (five or more medications) was 95% and 69% for hyper-polypharmacy (≥10 medications), far exceeding that observed in the general population; 77.5% had one or more severe potential drug-drug interaction.1

There has been a dramatic increase in the risk of drug-drug interactions and ADRs. Common cardiovascular ADRs in geriatric patients include acute kidney injury, bleeding and orthostatic hypotension which can lead to hospitalization. Of geriatric patients hospitalized for an ADR, 90% have been reported to have polypharmacy.2 In the aging population, the risk of an ADR is 82% if a patient is taking seven or more medications.3 Older patients with known cardiovascular disease are taking an average of 11 medications.1 Altogether, this means clinicians treating patients with cardiovascular diseases should be on high alert for ADRs and prescribing cascades.

Specific Challenges

Elderly patients are vulnerable to ADRs due to age-related changes in metabolism, leading to a higher risk of drug toxicity or interactions. With age comes cognitive decline and increased fall risk. Frequently used drug classes recognized by the American Geriatric Society Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults include antihypertensives, antiarrhythmics, antiplatelets and anticoagulants, and vasodilators.4-6 These drug classes are the most frequently reported cardiovascular medications implicated in adverse drug events. Medications don't work if the patient doesn't take them. Complex cardiovascular regimens make it difficult for elderly patients to adhere to prescriptions, leading to missed doses or overdosing, which can lead to worsening of their "treated" condition. Self-reported adherence to cardiovascular medications in patients who have coronary artery disease is for the combination of aspirin, beta-blocker and a lipid-lowering agent in surveys.7 The use of antiplatelet agents to prevent stent thrombosis, moderate- to high-dose statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes, or antihypertensive agents in asymptomatic patients may all be perceived by patients as not providing benefit because they may not feel the effects.8

Strategies to Address Polypharmacy

Geriatric syndromes along with polypharmacy complicate both diagnosis and treatment. To gain a better understanding of how to manage these issues with our patients, we talked with Nimit Agarwal, MD, lead geriatrician with the divisions of Geriatric Medicine, Banner Health, Banner University Medical Center-Phoenix and University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix in Arizona.

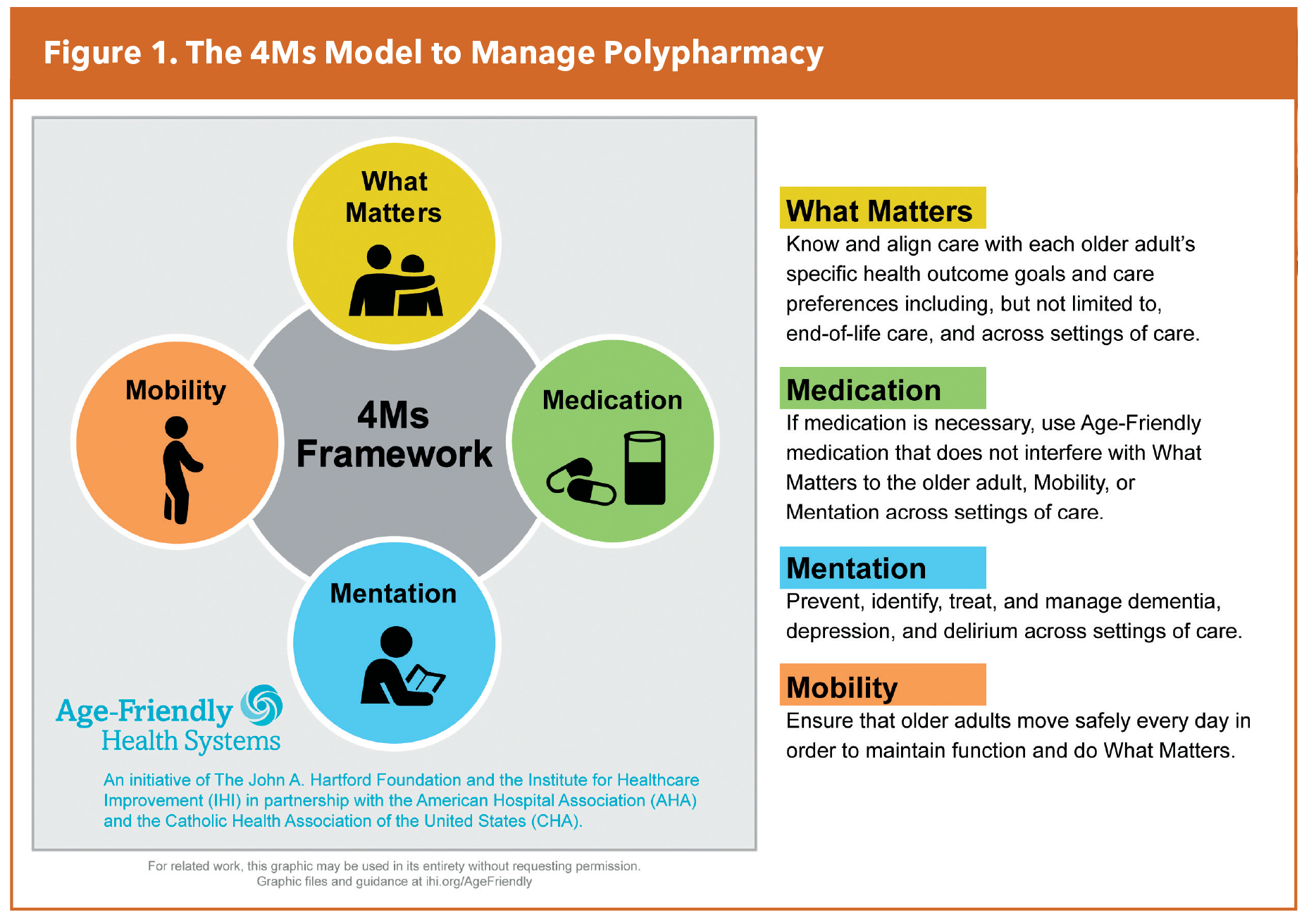

Agarwal's #1 piece of advice for cardiology clinicians caring for older patients? Employ a broader holistic approach to care for older patients. He recommends following the "4M" framework of care proposed by the Institute of Healthcare Improvement and adopted by geriatricians (Figure 1). The model, which focuses on what matters to older adults, medications, mentation and mobility, has had rapid uptake by clinicians as a better way to approach visits with older patients.

As part of this more holistic approach, used in the certified age-friendly system at his medical center, Agarwal advises clinicians to "ask a patient what matters most to them," before prescribing or adjusting a medication.

Furthermore, "think twice before adding any new medication," he says, being aware that each medication could have a good or a bad effect. Also, consider any new symptom as medication-related until proven otherwise in your older patients.

Prescribing cascades are common in this high-risk population. A part of this cascade is prescribing a medication for the purpose of treating an adverse effect of another prescription, as has become common these days, especially in relation to cardiovascular medications.

The Beers Criteria may be used to educate, increase awareness, and determine the severity and characteristics of harm. Incorporating this tool, along with the 4-M model can be utilized to improve care for your older patients. A key question for every clinician: Does the drug I'm prescribing align with what truly matters most to my patient?

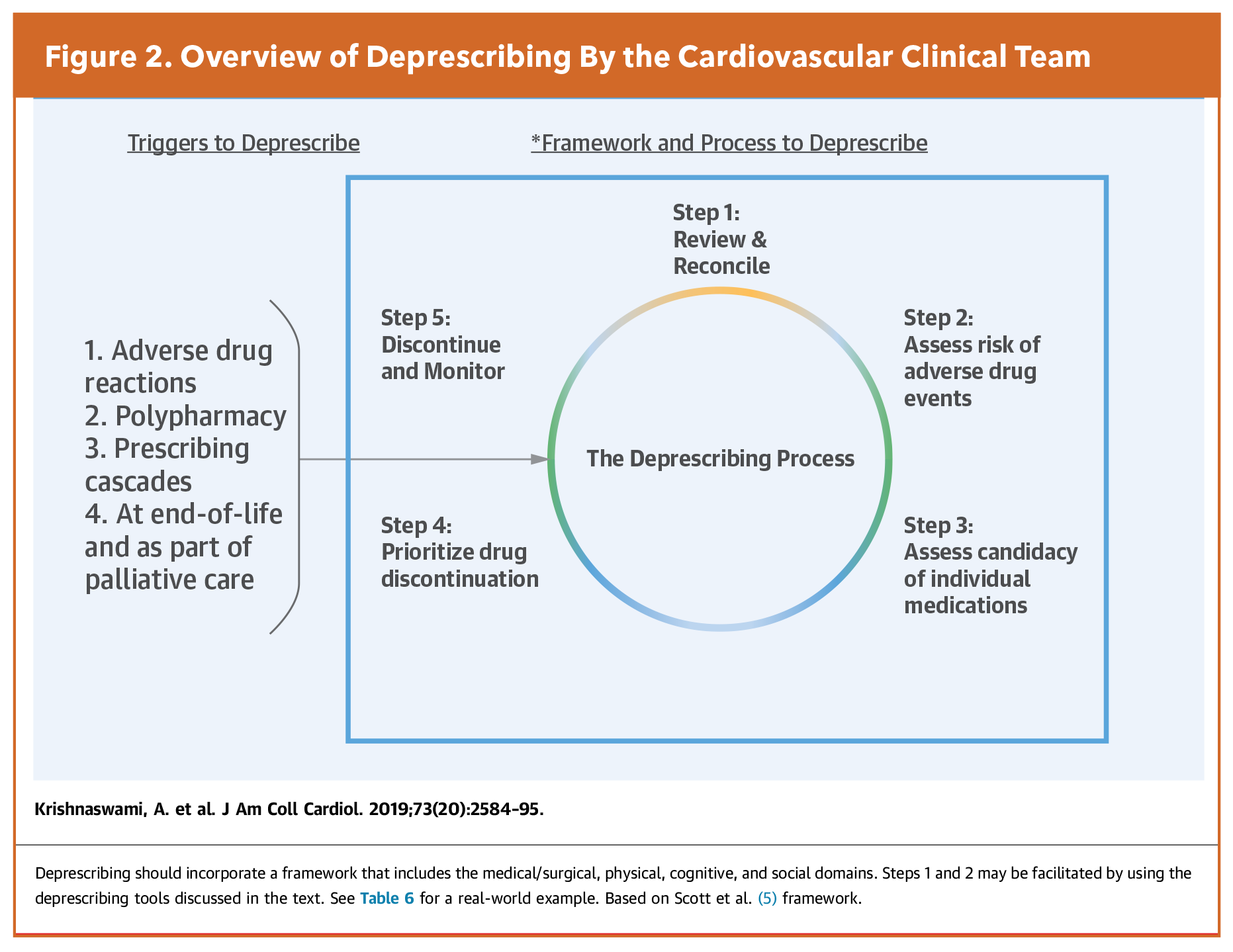

Deprescribing, the process of medication withdrawal or dose reduction to correct or prevent medication-related complications, improve outcomes and reduce costs, is an integral component of good prescribing practices, wrote Ashok Krishnaswami, MD, FACC, and colleagues from ACC's Geriatric Cardiology Member Section in a 2019 article in JACC.9 Noting the need for an informed and shared decision-making process and holistic approach, they discuss five steps for deprescribing (Figure 2).

The review and reconciliation for Step 1 should include all prescribed and over-the-counter medications and their indications as well as nonadherence patterns. In Step 2's risk assessment, they advise proactively investigating possible adverse effects because these may not be reported by patients. A variety of tools, also discussed in the paper, can assist with this process. As part of Step 3's assessment for discontinuation, consider medications used for symptom control that are no longer effective or symptoms have resolved, those that lack effectiveness or without a current indication, along with medications that "impose an unacceptable treatment burden." In Step 4, a discussion with the patient and family is required to determine the optimal sequence of discontinuation, based on risk/benefit balance, ease, risk for adverse drug withdrawal events and patient preference. In Step 5, potential adverse effects and monitoring plans should be discussed with the patient and drugs discontinued one at a time. The paper also provides a number of tables listing drugs that are potentially inappropriate cardiovascular drugs in older patients, may exacerbate an underlying disease state, and more.

Steps That Matter

"The reality is that polypharmacy is often a consequence of well-meaning care," observes Agarwal. "But it's essential to remember that each additional medication raises the potential for harm, especially in our older patients." The first step to improving care of older adults is to start incorporating the principle of "what matters most" in the care of our aging patients.

This article was authored by Nicole Murdock, PharmD, Elevation Health Partners, AZ; Kristen De Almeida, PharmD, Baptist Hospital of Miami, FL; Tania Ahuja, PharmD, FACC, NYU Langone Health, NY; and Brittany Messer, PharmD, CPP, FACC, Marshall Health, WV. All are members of ACC’s Cardiovascular Team Member Section.

References

- Sheikh-Taha M, Asmar M. Polypharmacy and Severe Potential Drug-Drug Interactions Among Older Adults with Cardiovascular Disease in the United States.BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:233:doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02183-0.

- Pedrós C, Formiga F, Corbella X, et al. Adverse Drug Reactions Leading to Urgent Hospital Admission in an Elderly Population: Prevalence and Main Features. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2016;72(2):219–226.

- Guthrie B, Makubate B, Hernandez-Santiago V, et al. The Rising Tide of Polypharmacy and Drug-Drug Interactions: Population Database Analysis 1995–2010. BMC Med 2015;13(74).

- Page RL 2nd, O'Bryant CL, Cheng D, et al. Drugs That May Cause or Exacerbate Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134(6):e32-69.

- American Geriatrics Society 2023 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(7): 2052-2081.

- Newby LK, LaPointe NM, Chen AY, et al. Long-Term Adherence to Evidence-Based Secondary Prevention Therapies in Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation. 2006;113: 203-212.

- Simon ST, Kini V, Levy AE, Ho PM. Medication Adherence in Cardiovascular Medicine. BMJ. 2021;374:n1493.

- Krishnaswami A, Steinman MA, Goyal P, et al. Deprescribing in Older Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2584-2595.

Clinical Topics: Geriatric Cardiology

Keywords: Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications, Medication Adherence, Drug Interactions, Polypharmacy, Hospitalization, Aged, Geriatrics