Feature | Bridging the Gender Gap in Heart Health: Women’s Specialized Clinics

When a young woman from an affluent Chicago neighborhood came to Annabelle Volgman, MD, FACC, complaining of palpitations before a ski trip, Volgman was shocked to learn the woman had never received an EKG despite months of symptoms. The simple test revealed Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, an easily diagnosable and treatable arrhythmia.

"I could not believe that anyone would be treated that way," Volgman says. "But apparently, there have been many women being treated so inappropriately."

That experience in the late 1990s spurred Volgman to create the Rush Heart Center for Women in Chicago in 2003, one of the first dedicated women's heart programs in the country. Two decades later, many mid-sized and most large cities have specialized heart clinics for women and Volgman's program treats thousands of patients annually.1

The need for heart clinics specifically focusing on women is critical. And sex-specific cardiovascular education of trainees and the entire care team is imperative," says Laxmi Mehta, MD, FACC, director of preventive cardiology and women's cardiovascular health at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus. While cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death for both women and men, significant gaps persist in how women are diagnosed, treated and studied compared with men.

"When you know there's a disparity between the genders, not having something streamlined to create equitable care for women is actually morally wrong," says Garima Sharma, MD, FACC, director of preventive cardiology and cardio-obstetrics and cardiovascular women's health at Inova Health System in northern Virginia. "If half the population doesn't get the care they deserve, then I think there's something wrong with the way society is treating them."

Widespread recognition of the biological differences between the sexes when it comes to cardiovascular health did not really begin until the early 1990s after Bernadine P. Healy, MD, FACC, published an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine highlighting the findings of two studies in that issue demonstrating clear evidence of sex bias in the management of coronary artery disease.2 It took until 1999 for the first consensus panel statement on preventive cardiology for women and 2004 for the first evidence-based guidelines.3,4

Importantly, women have numerous sex-specific risk factors in addition to non-sex-specific ones. These include hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, early or premature menopause, gestational diabetes, polycystic ovarian syndrome, autoimmune or other inflammatory diseases, and breast cancer therapies. Oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy can also affect risk, based on a woman's level of cardiometabolic risk. After menopause, when protective estrogen levels drop, women's cardiovascular risk rises dramatically.5

"These risk factors are associated with an increased risk of premature coronary artery disease, premature heart failure, premature stroke and premature mortality in women," adds Sharma.

Yet women's cardiovascular disease risk has long been underappreciated in clinical practice, particularly in the primary care setting. Women often don't discuss heart health with their clinicians and there is a significant gap in awareness and communication regarding cardiovascular disease risks among women and health care professionals.6,7

Even when women do seek care, they often face unconscious bias from medical providers, Volgman says, with their symptoms frequently dismissed as anxiety. But she notes the anxiety stems from them not knowing when their symptoms will occur again. "We need to learn the tools and how to deal with that anxiety well."

"In an effort to educate the health care communities and public, there have been numerous scientific statements and review papers on cardiovascular disease in women published in leading cardiovascular journals over the last decade," says Mehta. These have ranged from heart attacks, cardio-obstetrics, breast cancer, prevention and arrhythmias.8-13

The Solution: Specialized Cardiovascular Programs

Dedicated women's heart programs are designed to address these disparities, improving prevention, diagnosis and treatment, as well as provide an important population for clinical trials, which have traditionally underenrolled women. These centers take a multidisciplinary approach, bringing together cardiologists, OB-GYNs, endocrinologists and other specialists, physically or virtually to provide comprehensive care.

"As cardiologists, we can address their cardiovascular health," says Sharma. But she notes there are other aspects of care such as behavioral health that also impact cardiovascular health but cardiologists often don't screen for it. For instance, although depression, which is more prevalent in women, is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, cardiologists aren't trained to diagnose and treat it. This is one way that multidisciplinary care comes into play.

Rachel Bond, MD, FACC, is the system director of the Women's Heart Health Program at Dignity Health in Arizona, which she founded in 2018. "The premise of the program was to foster collaborative care," she says. "The benefits are enormous, as the targeted referrals include cardiologists who treat women but may not feel comfortable managing female-specific or predominant conditions. This model provides the opportunity for us to co-manage patients, ensuring comprehensive care." The result, she says, is improved outcomes, including reductions in hospitalizations and re-admissions.

Education forms a key pillar of the program, such as educating emergency room physicians about how women present with heart attacks compared with men. "This approach ensures they recognize the signs and symptoms, and order the appropriate tests, reducing the risk of missing a diagnosis," Bond says. Her group also provided education to obstetrics/gynecology clinicians about the numerous conditions that occur during pregnancy that can increase a woman's risk of future heart disease.

Bond's program also works with oncologists to address the cardiovascular risks of breast cancer treatments and with rheumatologists to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease resulting from inflammatory conditions like lupus, which is more prevalent in women.

Sharma's team created an EMR-based referral system to automatically flag women with preeclampsia for cardiac follow-up. It creates a direct referral at discharge from obstetrics/gynecology to cardiology, making it more convenient for the patient because the coordinator of the cardio-obstetrics program calls patients directly to schedule a virtual or in-patient appointment.

"We realized that after giving birth, patients with preeclampsia were seeing their obstetrician at six weeks but there wasn't a warm hand-off to cardiology," explains Sharma. The EMR flag in the referral system for a diagnosis of preeclampsia requires referral to the women's cardiology center. As a result of this referral, Sharma's data show that, compared to conventional care, "cardiovascular health screening goes up significantly," ensuring patients do not fall through the cracks and their heart health is addressed. "It's really empowering to the patient."

Bond's program incorporates experts in interventional cardiology, cardiothoracic surgery, electrophysiology, advanced heart failure and other subspecialties in cardiology. "This gives us the opportunity to work with the same team," she says. For instance, if a patient needs a coronary catheterization, we're working with the same interventional cardiologist who understands the different pathophysiology of women. "We work collaboratively to ensure we are providing more targeted care for each patient."

"The leading cause of maternal mortality s cardiovascular disease and it's often very preventable," explains Bond. Thus, she runs a monthly maternal heart council where physicians, advanced practice practitioners, nurses and hospital administrators meet to discuss prenatal, natal and postpartum care pathways for the entire health care system.

Program directors also draw on their own experiences to provide clinical guidance on sex-specific cardiovascular care. For instance, Volgman co-authored a paper highlighting how the Rush Heart Center for Women treats patients with ischemic heart disease (IHD). The paper specifically notes that it operates "differently than some traditional prevention centers because it assesses for obstructive as well as nonobstructive causes for IHD."14

Treating IHD in women "requires extensive knowledge about coronary functional testing, which is not widely used by a lot of interventional cardiologists," Volgman said, but should be. "That's the only way we can give women a definitive diagnosis for what's causing their chest pain."

Of course, the programs play an important role in research. "Women have historically been underrepresented in the cardiovascular clinical trials," Bond emphasizes. Currently enrollment of women is about 30% in many of the major cardiovascular trials on coronary artery disease or heart failure, but she says, the aim should be about 50%.

Targeted education based on a woman's race, ethnicity, age and social determinants of health is another service that women-focused clinics can provide, says Bond. "We take more of a holistic approach to care than other general cardiovascular practices."

Starting a Clinic

"For those interested in starting a heart center for women, I encourage them to learn as much as they can about this topic," Volgman says. An intentional educational program is needed to prepare to establish a center.

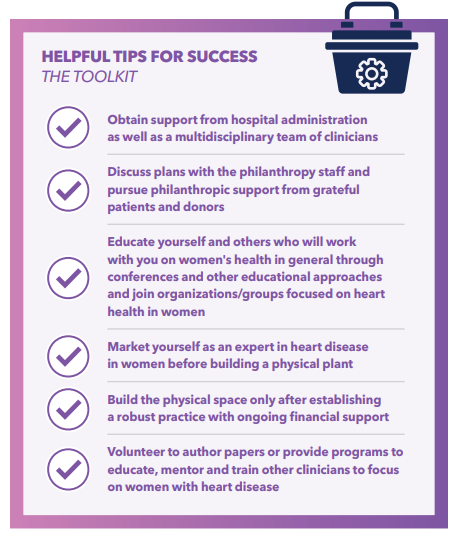

Volgman and Mehta co-chaired a group from ACC's Women in Cardiology Member Section that created a toolkit on how to establish a women's heart center. The toolkit covers every aspect of starting a specialized program from developing a mission statement, identifying funding, structure for academic and private practice clinics, specialties, areas of focus and infrastructure as well as setting performance metrics research and advocacy.

The toolkit defines a women's heart specialist as "a cardiologist who understands the sex differences in cardiovascular disease and has acquired knowledge through education, training and experience in treating women with cardiovascular disease."

Created in response to many inquiries about how to build a build a women's center, the resulting document "was a labor of love and the labor of many of the women who've done this successfully," says Volgman. "We came up with a great toolkit that provides a good understanding from beginning to end of what a clinic could look like," adds Bond, who, along with Sharma, also served on the toolkit committee.

Start small, Volgman advises. "Start with just opening up space in your practice. If you're interested in cardio-obstetrics, that's a segment that can be started by one cardiologist." And specialists at a woman's heart health clinic do not have be women, and she notes only about 20% of cardiologists in the U.S. are women.

Sharma highlights the need for a business focus to drive quality and excellence. "We must be business savvy about this," adding this is more than cardiologists wearing red dresses as a symbol.

In addition, she says, it's necessary to think about showing growth to the program funders. Focus on the potential to bring in new patients who aren't currently receiving cardiac care. When she started her program, Sharma showed there was the potential to bring in about 6,000 patients with preeclampsia who were not being seen by cardiology.

Volgman's program receives significant financial support from grateful patients and other philanthropic sources. The Ohio State University program began when a grateful patient asked the chief of cardiology how to improve women's cardiovascular care. Recently, she expanded her philanthropy to create a multidisciplinary research hub focused on diagnosing, treating and preventing diseases that disproportionately affect women. "This reflects our patients' drive for better care, not just for cardiovascular disease, but for all conditions impacting women,"says Mehta.

These specialized programs are showing promising results. For instance, Sharma's demonstrated significant improvements in screening rates and outcomes for postpartum women with cardiac risk factors.

"We're bringing in new patients, we're adding value, being patient-centered, and, most importantly, improving care," she says. "You can't put a dollar amount on saving a mother's life."

Learn More at ACC.25

Plan now to attend ACC.25, being held March 29-31 in Chicago, to keep the learning going. Visit ACCScientificSession.ACC.org to register. Access the Online Planner. Look for Session 204 looking at the intersection of sex and hypertension, Session 241 looking at the intersection of cardio-obstetrics and heart failure, and Session 908 on hot topics in cardio-obstetrics, and more.

Don't miss the Keynote by Brittany Weber, MD, PhD, FACC, on Sunday, March 30, titled Cardiovascular Health in Special Populations: CardioRheum, CardioOb, CardioNeuro and CardioSex.

References

- Lundberg GP, Mehta LS, Sanghani RM, et al. Heart Centers for Women; Historical Perspective on Formation and Future Strategies to Reduce Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2018;138:1155-1165.

- Healy B. The Yentl Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(4):274-276.

- Mosca L, Grundy SM, Judelson D, et al. AHA/ACC Scientific Statement: Consensus Panel Statement. Guide to Preventive Cardiology for Women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(6):1751-1755.

- Mosca L, Appel LJ, Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-Based Guidelines for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Women. Circulation. 2004;109(5):672-693.

- Lucà F, Abrignani MG, Parrini I, et al. Update on Management of Cardiovascular Diseases in Women. J Clin Med. 2022;11(5):1176.

- D'Alton M, Tolani S. The Well-Woman Visit: Time to Get to the Heart of the Problem. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2018;132(1):3-5.

- Bastiany A, Towns C, Kimmaliardjuk DM, et al. Engaging Women in Decision-Making about their Heart Health: A Literature Review with Patients' Perspectives. Can J Physiol. 2024;102:431-441.

- Mehta L, Beckie T, DeVon H, et al. Acute Myocardial Infarctions in Women. Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(9):916-947.

- Mehta LS, Watson KE, Barac A, et al. Cardiovascular Disease and Breast Cancer: Where These Entities Intersect: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(8):e30-e66.

- Mehta LS, Warnes CA, Bradley E, et al. Cardiovascular Considerations in Caring for Pregnant Patients: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(23):e884-e903.

- Mehta LS, Velarde GP, Lewey J, et al. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Women: The Impact of Race and Ethnicity: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;147(19):1471-487.

- Davis M, Arendt K, Bello N, et al. Team-Based Care of Women With Cardiovascular Disease From Pre-Conception Through Pregnancy and Postpartum: JACC Focus Seminar 1/5. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(14):1763–1777.

- Lindley K, Bairey Merz C, Davis M, et al. Contraception and Reproductive Planning for Women With Cardiovascular Disease: JACC Focus Seminar 5/5. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(14):1823-1834.

- Khandelwal A, Bakir M, Bezaire M, et al. Managing Ischemic Heart Disease in Women: Role of a Women's Heart Center. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2021;23:56.

Clinical Topics: Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Prevention, Vascular Medicine, Hypertension

Keywords: Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications, Menopause, Hypertension, Pregnancy-Induced, Sex Factors, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, Cardio-Obstetrics