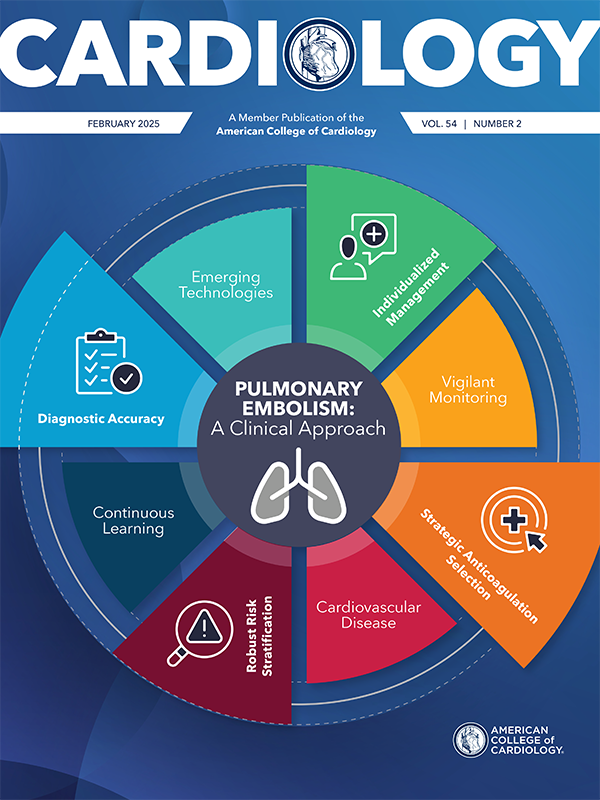

Editors’ Corner | Steps in the Treatment of Pulmonary Embolism (Watch Out! The Staircase is Tricky!)

Pulmonary embolism (PE) mortality has increased over the past decade and racial and geographic disparities persist. Black women and men have an approximately two-fold higher age-adjusted mortality rate compared with White women and men, respectively. Similar trends are seen in geographical regions. Age-adjusted mortality rates for younger adults (25-64 years) have increased (average annual percent change 2.1%) and have remained stable for older adults >65 years.

In the clinical trenches, PE challenges clinicians with its complex presentations and its potential for producing rapid clinical deterioration. PE is the third leading cause of cardiovascular mortality in the U.S. – following myocardial infarction and stroke, and claims over 40,000 lives every year. It accounts for about 40% of the >1 million hospitalizations for venous thromboembolism in the U.S.1

In the emergency department (ED), physicians have a low threshold for moving to diagnostic testing for PE. However, almost paradoxically, the first steps in the ED should be to test for PE probability by using Wells or Geneva Scores – thereby identifying low-risk patients for PE and avoiding unnecessary high cost imaging and potentially even avoiding the complications of anticoagulant therapy. Once patients are identified as low risk for the diagnosis of PE, efforts of the Pulmonary Embolism Response Team (PERT) can then be focused on the much more complex decision-making in patients with a higher likelihood of having PE and making steps that will be needed for further risk stratification and more advanced therapy.

In this month's issue of Cardiology, Geoffrey D. Barnes, MD, MSc, FACC, and Gregory Piazza, MD, MS, FACC, outline the latest strategy of how best to treat the wide variety of patients who present with possible PE. After identifying those patients with a low likelihood of a PE diagnosis, they then carefully walk us through the next series of steps needed for patients after a definitive PE diagnosis – first an assessment using the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index to further risk stratify them into low, intermediate and high-risk categories. This is where it begins to get tricky – the tools used for such risk analysis are not exact, and ongoing clinical reassessment of patients as they begin therapy is mandatory for optimizing care.

The next steps become critical and difficult, primarily because there is lack of certainty in determining individual patients who might, for example, need hemodynamic support, or more complex systemic thrombolysis, surgery or even extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Treatment of intermediate- and high-risk PE patients is a daunting task, and may require the multispecialty expertise of more than a cardiologist (think cardiac surgery, interventional radiology, vascular medicine, pulmonary medicine, anesthesia).

Finally, the cover story tackles the list of emerging technologies becoming more and more common in the treatment of high-risk or catastrophic PE. Despite the appeal of removing clot using transcatheter techniques, do these novel strategies have data to support routine use? The article even covers the nuanced use of thrombolytic therapy as needed. Does tenectaplase have an emerging role, and what are the potential contraindications for thrombolysis?

My takeaways from this cover story are many, and it is certainly worth a read for any physician, and especially cardiologists, who care for patients with PE. There is a lot still to be discovered and understood about the urgent treatment of PE, but this article is a great cornerstone of information on which to develop the necessary patient-specific care for this complex problem.

Peter C. Block

MD, FACC

February is American Heart Month and an opportunity for cardiovascular clinicians across the care team to redouble efforts to educate our patients, communities and the broader public about the impact of – and how to prevent – cardiovascular disease. Be sure to turn to page 20 to learn about the benefits of clinics dedicated to women's heart health, and page 22 to learn about the stark disparities in life expectancy across the country, to which cardiovascular disease is surely a contributor. And learn about health and well-being coaching and how these professionals can help us with preventing and treating cardiovascular disease in Prioritizing Health.

Enjoy this issue! As always, please send your thoughts and feedback to CardiologyEditor@acc.org.

- Martin KA, Molsberry R, Cuttica MJ, et al. Time trends in pulmonary embolism mortality rates in the United States, 1999 to 2018: J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9: e016784.

Clinical Topics: Cardiovascular Care Team, Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism, Vascular Medicine

Keywords: Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications, Clinical Deterioration, Myocardial Infarction, Pulmonary Embolism, Venous Thromboembolism