Focus on Heart Failure | Clinical Considerations to Unlock the Potential of LVAD Therapy

Back to the Future: Clinical Considerations to Unlock the Potential of LVAD Therapy

For select patients with advanced heart failure (AHF), durable left ventricular assist device (LVAD) therapy can be a life-sustaining option that improves quality of life. Since its introduction a few decades ago, the technology and associated clinical outcomes have evolved in a transformational manner. When the current generation HeartMate 3 LVAD debuted in 2017 with its fully magnetically levitated frictionless pump design, it represented a significant leap forward in terms of the hemocompatibility-related adverse events (complications that arise from the interaction between blood components and the device) that plagued legacy devices.

HeartMate 3, approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, demonstrated a near elimination of pump thrombosis, substantial reduction in stroke rates and a decrease in bleeding-related complications.1 For a disease that otherwise has a median survival of well less than one year after patients become inotrope-dependent, data from MOMENTUM 3 demonstrated with HeartMate 3 survival rates of 88% at one year, 83% at two years and 58% at five years – yielding a median survival benefit of more than five years.2,3

These survival gains are even more marked for certain patient subgroups (more than one-third of the MOMENTUM 3 cohort) in whom five-year survival is comparable to that post heart transplant.4 Similarly, there are substantial and meaningful gains in quality of life associated with HeartMate 3 LVAD implantation. More than 75% of patients achieve and sustain NYHA functional class I-II at two years after implant, along with a 30-point gain in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire scores.2,3 Real-world registries of HeartMate 3 LVAD patients have shown similar results.5

Despite the encouraging data, adoption of LVAD technology has remained critically deficient. Implant volumes have remained flat at <3,000 per year since 2021, with destination therapy intent (implantation for long-term support, in patients who are not candidates for heart transplant) accounting for about 80% of all implants in the U.S. since the 2018 adult heart allocation amendment that lowered listing priority for stable LVAD patients.6

Notably, HF, progression to advanced stages and related mortality have continued to rise in the U.S. Epidemiological estimates suggest there are about 300,000 patients with AHF – highlighting a large, underserved population of patients who are potential candidates for LVAD therapy.7

Gaps in utilization are even wider for certain patient subgroups, including women, Black, older and socially vulnerable patients.8,9 Therefore, for the clinical community, there is a need to enable translation of device breakthroughs to impact care at the bedside by: 1) equipping general and community cardiologists, internal medicine and critical care physicians with the tools needed to recognize the often-elusive signs of AHF and initiate timely referrals to AHF centers, and 2) revisiting stringent patient selection criteria for LVAD therapy in light of current generation pump technology.

Identifying Candidates For LVAD Therapy

LVAD therapy is lifesaving for patients with AHF, however successful outcomes hinge on appropriate timing of implantation. For example, patients with advanced and irreversible end organ dysfunction as a result of HF, and those with progressive right ventricular (RV) dysfunction (in many cases a sequela of longstanding LV dysfunction), are generally considered suboptimal candidates for therapy, and they do not enjoy the same extent of survival benefit from the therapy.

The HeartMate 3 Risk Score, developed and validated in the MOMENTUM 3 cohort to predict one- and two-year survival post implant, assigns increased risk to lower serum sodium, higher blood urea nitrogen and elevated right atrial pressure:pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, a robust marker of inherent RV dysfunction.10

In practice, however, recognition of AHF, particularly the large ambulatory AHF population (stage C2D disease) can be difficult.7 Criteria to assist with identification have been proposed by several groups. One example is the I-NEED-HELP mnemonic, a constellation of nine characteristics known to be associated with AHF and to portend high risk of mortality.11

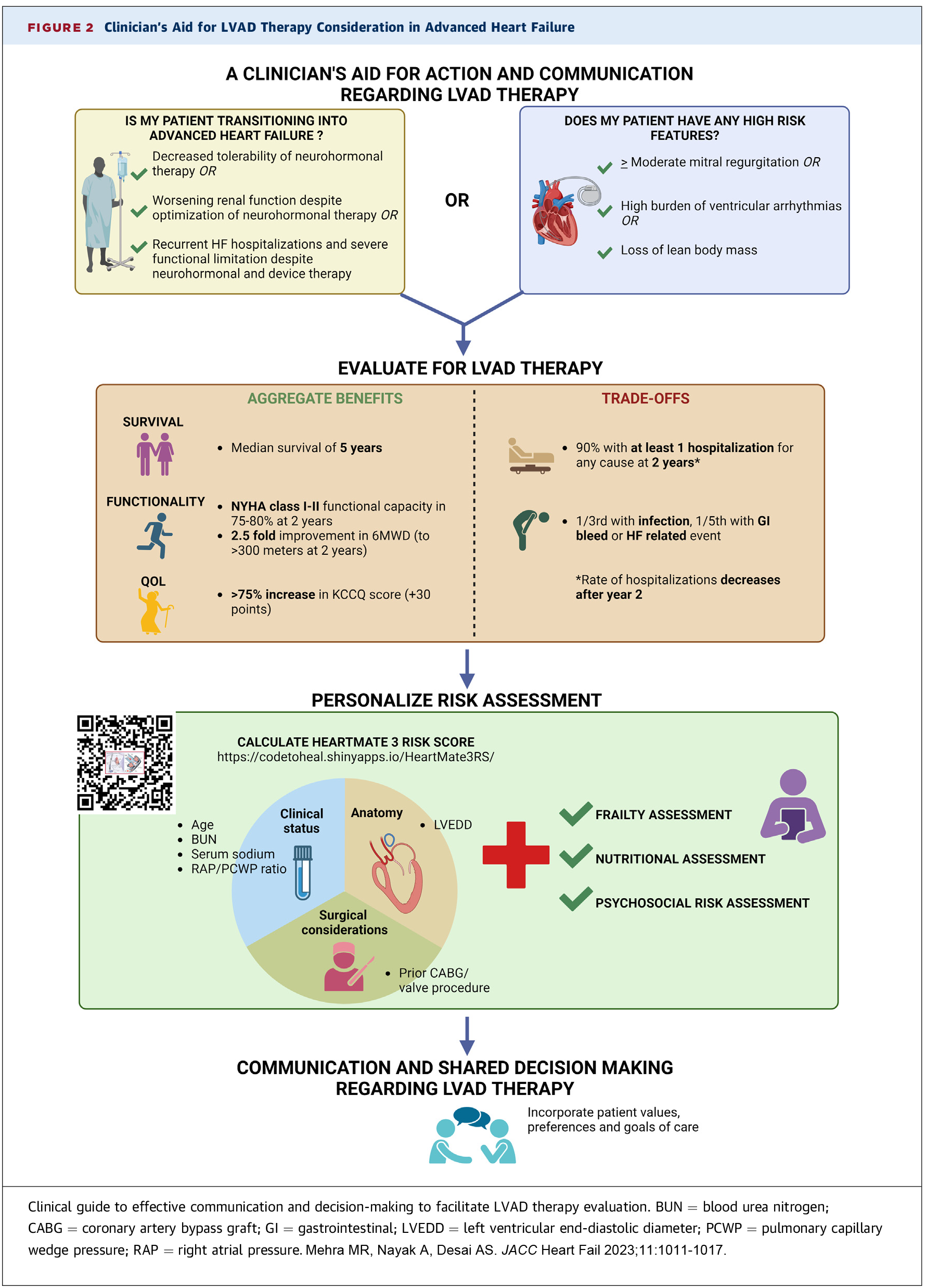

A simpler aid developed by Mehra, et al., and published in JACC: Heart Failure,3 includes just three markers of transition to AHF plus three high-risk features:

Markers of Transition to Advanced HF

- Decreased effectiveness and/or tolerability of neurohormonal therapy

- Worsening renal function

- Significant HF-associated morbidity (recurrent hospitalizations and/or significant functional limitation, etc.)

High-Risk Features

- Loss of lean body mass

- Worsening functional mitral regurgitation

- High burden of ventricular arrhythmias

Patients identified using these criteria benefit from urgent referral to a center with AHF therapy capabilities, along with initial conversations eliciting their values, explaining the prognosis and introducing the concept of AHF therapies.12

Among ongoing efforts to establish objective criteria and further streamline identifying patients who would benefit from advanced therapies is the TEAM HF trial. With an enrollment target of approximately 850 patients worldwide, it will study whether patients with persistently elevated pulmonary artery (PA) pressures (mean PA pressure ≥30 mm Hg, measured via the CardioMEMS PA sensor) despite guideline-directed medical therapy, represent a high-risk cohort that would benefit from early intervention with LVAD therapy.13

Patient Selection For LVAD Therapy

Patients referred to AHF centers undergo a thorough medical and psychosocial vetting process that determines their candidacy for surgical therapies. The goal of this process rooted in "primum non nocere" ("do no harm"): to identify patients who are too medically ill to withstand LVAD surgery, have psychosocial barriers to care that would impede their ability to successfully manage an LVAD, and ultimately to only offer the therapy to those in whom benefit clearly outweighs risk.

Although there is a paucity of registry data that tracks patients who are referred for but ultimately denied advanced therapies, single center data suggest that up to one-third of referred patients are ultimately deemed not to be candidates for LVAD therapy, and that 25% of these denials are for psychosocial reasons.14

Considering the remarkable technological advances with the current generation HeartMate 3, a pump that is very forgiving in terms of anticoagulation adherence and offers more than five years of median survival benefit, there is a pressing need to develop patient selection criteria relevant to the current era.

Recent Intermacs registry analyses have found that baseline psychosocial risk and social support do not predict survival benefit from LVAD therapy, particularly in younger patients.6,15 Older patients including those ≥70 years old, an underrepresented cohort for advanced therapies, also derive excellent survival and quality of life benefit from HeartMate 3 therapy.

While priority on the heart transplant waiting list shifted in 2018 away from stable LVAD patients, there is a need to shift the view away from LVAD therapy and heart transplantation as being mutually exclusive options to being complementary therapies in selected patients.

In patients <50 years old, the HeartMate 3 implant confers a >90% survival at one year, and close to 75% survival at five years.6 While heart transplant outcomes are excellent, median graft survival remains about 13 years, and the very real risk of waitlist mortality is often not discussed with patients.16 Taken together, for the younger patient, a bridge to transplant LVAD strategy may offer more "net prolongation of life."6 Additionally, LVAD therapy offers the possibility of myocardial recovery. Therefore, for patients eligible for either therapy, a balanced shared decision-making encounter is requisite.

Three different tools can help to tailor population-level data to an individual patient: 1) the HeartMate 3 Risk Score predicts survival benefit from LVAD therapy, 2) the RecoverHeart Score predicts chances of reverse remodeling after therapy, and 3) the U.S. Candidate Risk Score estimates waitlist mortality for candidates awaiting heart transplant.10,17,18

Clearly, these over-simplified concepts of extension of life must also be balanced against trade-offs of LVAD therapy. Currently, LVAD patients continue to lead a very medicalized lifestyle, with one single center study demonstrating that acquiring health care consumes about one-quarter of their days alive with the device.19 Readmission burden continues to be substantial, with 90% of patients being readmitted for any cause in the first two years post implant.20

Living with an LVAD requires a significant lifestyle change and commitment from patients and their caregivers. Ultimately, these shared decision-making conversations must center on individual patient's values, their goals and preferences.21 Tools such as the DECIDE-LVAD aid can help elicit patient's values and assist with making values-congruent health care decisions.22

The Way Ahead: A Call to Action

While the HeartMate 3 LVAD is currently the only commercially available LVAD in the U.S., exciting times are upon us with several devices recently achieving critical clinical milestones in the journey from the engineering bench to the bedside.

The CorWave LVAD was recently and successfully implanted in a patient for the first time. Under development by Corwave in France, this device uses an undulating discoidal wave membrane to propel blood, with potential for improved hemocompatibility and more physiologically responsive hemodynamics. Similarly, in 2024, FineHeart SA in France announced the first-in-human implant of the FlowMaker device. It is a fully implantable cardiac output accelerator that provides support by means of a pump affixed to the LV apex and extending into the LV outflow tract, where an impeller spins to accelerate blood flow out of the native aortic valve.

The BrioVAD device has successfully advanced from the safety phase to the pivotal phase of being tested in clinical trials. This device has a smaller profile with more ergonomic peripherals (a narrow and flexible driveline, lighter peripherals), and is being developed by BrioHealth Solutions in the U.S.

On the total artificial heart (TAH) side, the BiVACOR was recently implanted in five patients in the U.S., marking the successful completion of the initial phase of its early feasibility study. A compact TAH that simultaneously supports the left and right circulation with two centrifugal impellers affixed to one magnetically levitated rotor, it is being developed by BiVACOR Inc.

Even as we celebrate these achievements, we must ask what we, as a clinical community, are doing to support investment and advance innovations in the field.

The current generation HeartMate 3 has already disrupted the technology landscape – with exceptional outcomes observed for patients, agnostic to demographics and psychosocial risk. Yet, despite being the only scalable treatment for advanced HF, LVAD therapy utilization has been woefully stagnant.

There is a need to simplify identification of candidates for therapy, refine patient selection and reconsider the clinical strategy to offer this life-sustaining therapy equitably and effectively for all. It is imperative that the clinical community collectively addresses the widening implementation gap, to continue to spur innovation and investment in the field, and to add "years to life and life to years" for our patients with advanced HF.

This article was authored by Aditi Nayak, MD, MS, FACC, at the Center for Advanced Heart and Lung Disease, Baylor University Medical Center, The Heart Hospital, Dallas, TX.

References

- Mehra MR, Uriel N, Naka Y, et al. A fully magnetically levitated left ventricular assist device. New Engl J Med 2019;380:1618-27.

- Mehra MR, Goldstein DJ, Cleveland JC, et al. Five-year outcomes in patients with fully magnetically levitated vs axial-flow left ventricular assist devices in the MOMENTUM 3 randomized trial. JAMA 2022;328:1233-42.

- Mehra MR, Nayak A, Desai AS. Life-prolonging benefits of LVAD therapy in advanced heart failure: a clinician's action and communication aid. JACC Heart Fail 2023;11:1011-17.

- Nayak A, Hall SA, Uriel N, et al. Predictors of 5-year mortality in patients managed with a magnetically levitated left ventricular assist device. JACC 2023;82:771-81.

- Schmitto JD, Shaw S, Garbade J, et al. Fully magnetically centrifugal left ventricular assist device and long-term outcomes: the ELEVATE registry. Eur Heart J 2024;45:613-25.

- Meyer DM, Nayak A, Wood KL, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Intermacs 2024 annual report: focus on outcomes in younger patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2025;119:34-58.

- Dunlay SM, Pinney SP, Lala A, et al. Recognition of the large ambulatory C2D Stage of advanced heart failure—a call to action. JAMA Cardiol 2025;10:391-8.

- Nayak A, Hicks AJ, Morris AA. Understanding the complexity of heart failure risk and treatment in black patients. Circulation: Heart Fail 2020;13:e007264.

- DeFilippis EM, Truby LK, Garan AR, et al. Sex-related differences in use and outcomes of left ventricular assist devices as bridge to transplantation. JACC: Heart Fail 2019;7:250-57.

- Mehra MR, Nayak A, Morris AA, et al. Prediction of survival after implantation of a fully magnetically levitated left ventricular assist device. Heart Fail 2022;10:948-59.

- Baumwol J. "I Need Help"—A mnemonic to aid timely referral in advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017;36:593-4.

- Morris AA, Khazanie P, Drazner MH, et al. Guidance for timely and appropriate referral of patients with advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021;144:e238-e250.

- TEAM-HF Trial. Accessed Sept. 25, 2025. Available here. www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06526195

- Yu S, Cevasco M, Sanchez J, et al. Considerations for referral: what happens to patients after being turned down for left ventricular assist device therapy. J Cardiac Fail 2020;26:300-7.

- Steinberg RS, Wang J, Cowger JA, et al. The association of provider-assessed psychosocial risk with outcomes in destination therapy left ventricular assist device patients: an Intermacs Registry Analysis. ASAIO Journal 2025;71:e116-e119.

- Cascino TM, Ling C, Likosky DS, et al. A gift of life, not immortality: evaluation of a strategy of heart transplant listing in the older patient with advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 2025;44:995-9.

- Drakos S. Recovery from Advance HF: Candiate Selection, Durability and Magnitude of Opportunity. Presentation available here. www.tctmd.com/slide/recovery-advance-hf-candidate-selection-durability-and-magnitude-opportunity

- Zhang KC, Narang N, Jasseron C, et al. Development and validation of a risk score predicting death without transplant in adult heart transplant candidates. JAMA 2024;331:500-9.

- Chuzi S, Ahmad FS, Wu T, et al. Time spent engaging in health care among patients with left ventricular assist devices. Heart Failure 2022;10:321-32.

- Vidula H, Takeda K, Estep JD, et al. Hospitalization patterns and impact of a magnetically-levitated left ventricular assist device in the MOMENTUM 3 trial. Heart Fail 2022;10:470-81.

- Steinberg RS, Carlisle RA, Shelton C, Hall SA, Nayak A. Equip, engage, empower: Considerations for effective values elicitation in the LVAD population. J Cardiac Fail 2025:S1071-9164.

- Allen LA, McIlvennan CK, Thompson JS, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention supporting shared decision making for destination therapy left ventricular assist device: the DECIDE-LVAD randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:520-9.

- Dual SA, Cowger J, Roche E, Nayak A. The future of durable mechanical circulatory support: emerging technological innovations and considerations to enable evolution of the field. J Cardiac Fail 2024;30:596-609.

Clinical Topics: Cardiac Surgery, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Cardiac Surgery and Heart Failure, Acute Heart Failure, Mechanical Circulatory Support

Keywords: Cardiology Magazine, ACC Publications, Heart-Assist Devices, Quality of Life, Heart Failure