The Patient’s Voice | A View From the Other Side

All of us who care for patients with heart disease see patients with complex and at times life-threatening issues. Our training concentrates expertise by helping us think through the complicated clinical problems that such patients present to us. Take, for example, a patient with mitral regurgitation (MR) in atrial fibrillation with new right heart failure due to secondary tricuspid regurgitation (TR).

We have learned what the next steps need to be and what questions need answers. How severe is the MR? How big is the left atrium? What is the left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic pressure and the wedge pressure? What is the pulmonary artery pressure? What is the right ventricular pressure? How well maintained are the right and LV ejection fractions (EF)?

A full work-up must begin with a cardiac echo (a transesophageal echo as well) to reveal the valvar pathology and its 'fixability," followed by a cardiac catheterization and coronary angiogram, and then a visit with a cardiac surgeon. Then comes the decision-making.

Structural heart programs have, over the last two decades, clarified the data that are incorporated in ACC/AHA guidelines and help us make those recommendations/decisions properly. We know that if the LVEF is at the lower limits of normal in the presence of severe MR, the left ventricle is already laboring to maintain forward cardiac output. Conservative therapies will ease symptoms but will not improve ventricular function. In fact, ventricular function will deteriorate over time. Thus "fixing" the valvar problems in many instances is the appropriate strategy. Easy for us to say.

Now, stop and think of yourself as a patient facing this decision.

Now, stop another beat and think of yourself as a cardiologist who is that patient's husband.

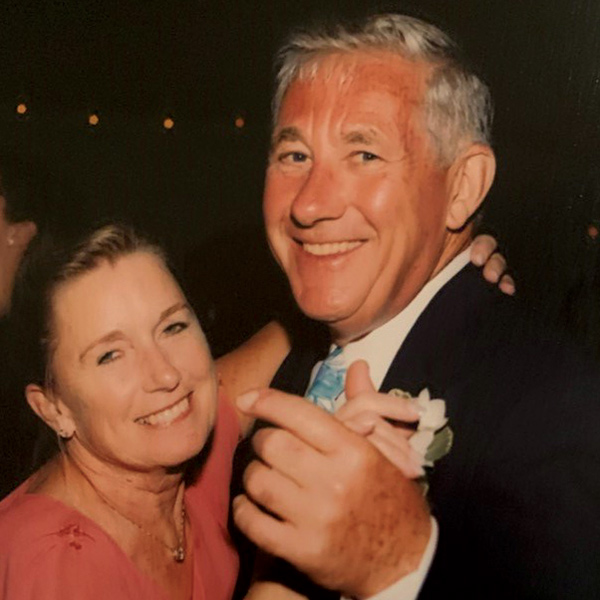

Recently, my wife Betsy was the patient in this scenario. I learned some valuable lessons from being on the other side of the desk and being the patient's partner and caretaker.

For Betsy the decision was relatively easy. She had been my research coordinator ever since the first "NHLBI PTCA Registry" so many years ago. During the halcyon days of transcatheter interventions for coronary and then structural heart disease, she had overseen multiple clinical trials. With a schoolteacher's background, Betsy learned to interview patients, gained their consent, watched their operations, and shepherded them through all kinds of procedures – all the while becoming one of the best cardiologists and patient advocates I know.

Betsy recognized that she was slowly becoming more and more symptomatic. The only solution for her was to "fix the problem" and feel better. As I dropped her off for what was to be a possible mitral repair, a tricuspid ring and a Maze procedure, she asked if it was okay that she was a little scared. The cardiologist in me answered "of course," adding that Day 2 post-op was going to be the hardest, that toughness was important, and that hopefully she would be home in about five days. So much for good thoughts. Betsy was in hospital for the next 16 days, nine of them in the ICU. COVID-19 rules kept me from ever visiting her.

The Long and Winding Road

Surgery was at 0700. A call from anesthesia an hour later thankfully told me things were going well. Then there was silence for the next 8.5 hours until the surgeon called. He tried to be reassuring as he recounted the unexpected pericardial scarring from a long-ago episode of pericarditis, the irreparable mitral pathology and the inability to repair the tricuspid as well. Together this resulted in a longer pump run, mitral and tricuspid replacement, a double Maze, difficulty with pacing, need for the intra-aortic balloon pump, lots of pressors, and persistent retrocardiac bleeding, finally controlled, from a scarred myocardial/pericardial surface.

The first of my many texts and emails went out to family and friends. A 9 p.m. call from the nurse in the ICU told me things were stable. That was a relief, but then a 4 a.m. call a few hours later told me of a single seizure. A CT scan of her head was negative, but I knew that was only minimally reassuring. It was a long night and a longer next day. Not much changed.

Treasured calls came from the ICU staff in the morning and evening as well as from the surgeon. I had to become a bystander, and my cardiology experience served only to manufacture desperate scenarios in my brain. I watched the clock and walked the dog, watched the clock, then walked the dog again, and then again.

I was given a number to call if I did not hear from the ICU the next morning. When I called, I was told things were a bit better hemodynamically, but there was no purposeful movement from Betsy. Remarkably our dog recognized when I intermittently came apart and tried to comfort me.

The day dragged on as I ran through more worst case scenarios. Late that afternoon a call came from the ICU nurse with a suggestion that seemed bizarre to me but turned out to be brilliant. Would I join a Zoom call to Betsy? Perhaps a voice she recognized would get through? I hesitated, not wanting to see her intubated, all ports spouting lines and support apparatus. But the nurses said they simply could not get through to her, and I needed to try.

Five minutes later they fired up an iPad in her room and there she was. "Betsy" I said, "it's me, Peter. Move your right arm!" The arm moved but not much. "Now wiggle your feet!" Both feet moved. "Now move your left arm!" She paused, then nodded "No!" The nurses laughed, and it was clear to all of us that she was still somewhere in there. I sent a picture of our dog, Zoro, from my phone to the iPad. She looked and smiled. The nurses and I cheered. Zoro comforted me.

From then on it was slow, but each day was better. Extubated three days later, balloon pump out, pressors weaning. Calls came to me from her nurses each day times two. After Betsy was extubated, I could call her directly. The surgeon and a fabulous ICU attending talked with me each day as well. The ICU attending, always upbeat, had the final say. He felt that the coma issues were likely complex, but a major contributor was Betsy's sensitivity to opioids. If so, she should be better on Post-op Day 4 or 5.

Saturday night on Day 5, two hours after my usual 9 p.m. call with the nurses, my cellphone rang. Terror – but then I saw it was Betsy's phone. "I need to get out of here," she slurred. "I am in a rotating Hell. The whiteboard on the wall says it's January 21. I sleep and when I wake up, it's always still January 21. It's like 'Groundhog Day.'" Nine days in the ICU, and then discharged to home on Day 16 carrying >20 pounds of extra volume. No one even suggested rehab during COVID!

Recovering at Home

Soon after Betsy arrived home, I was reminded of what I already knew – nurses are the heavy lifters in cardiac care. I had to become one (though poorly qualified). A living room lounge chair turned into a bed, sleep came in two-hour segments, diuretics were given according to daily weight, meds dispensed twice a day, legs wrapped and then unwrapped, positions changed, walks to the bathroom supported. Each day I juggled meds, took vital signs, hoped that potassium was not sliding, that creatinine was not rising, and kept buying bananas and orange juice. Home health nurses and therapists came and went. Visits were welcome but brief. Slowly, slowly, day by day.

Our story has a good ending. I write this two months after that first operative day. Betsy is now 23 pounds below her post-op weight, ankles are slim, and she has become Betsy again. Home health and home rehab discharged her after two weeks. We walk our dog together, though only short walks. I used to tell post-op cardiac patients that their surgeons will say they will heal in six weeks, but their cardiologist will tell them they will be healed in six months. I still believe this.

Patient Care is Family Care

As cardiologists and cardiac surgeons caring for post-op patients, our first task is to be dispassionate pathophysiologists. Acute, complex heart disease demands careful therapies. We learn that. But what I learned from "the other side" of this story is that we should never forget what families endure during the desperate times of illness uncertainty. Terror, helplessness and fright barely scratch the surface.

I owe the ICU staff and the attending physicians a huge debt of gratitude for supporting me by keeping me in the loop with their repeated updates and their commitment, even though they were flat out busy. That Zoom meeting was so outside the box, but a brilliant move. I will never forget that. Even small bits of progress are precious to those waiting for news. Take heed!

Home care is a complex issue. One of my teachers once said that hospitals are no place for a recovering patient. I get that. I also understand that patients want to go home and that hospitals need the beds. At discharge we all prescribe home nursing, physical therapy and occupational therapy, but they are easy to take for granted.

Most patients don't have an in-house cardiologist. I wonder how those first weeks of anticoagulation, diuretics, electrolyte replacement, gradual (but not too rapid) extra-cellular volume loss, and pulmonary physiotherapy at home play out for many patients and their families. I can attest that it does not go as smoothly as we assume. An additional weekly call from a primary care physician or treating cardiologist seems to me not enough oversight. Managing all of this is a challenge that needs to be met with more precision. A larger home health care footprint might be a good start. Perhaps our recent need for video visits could be used to great advantage for such patients. Easy for me to say.

Last week I finally had the opportunity to thank Betsy's ICU attending in person for his care and daily calls to me. During our conversation, he said it best – "I know how to take care of a complicated cardiac patient, but I try never to forget that I am treating the whole patient, including the family. Good advice for all of us – gratefully accepted by me."

Clinical Topics: Anticoagulation Management, Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiovascular Care Team, COVID-19 Hub, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Noninvasive Imaging, Pericardial Disease, Valvular Heart Disease, Anticoagulation Management and Atrial Fibrillation, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias, Acute Heart Failure, Interventions and Imaging, Interventions and Structural Heart Disease, Angiography, Computed Tomography, Nuclear Imaging, Mitral Regurgitation

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Analgesics, Opioid, Anesthesia, Angiography, Atrial Fibrillation, Anticoagulants, Blood Pressure, Cardiac Catheterization, Cicatrix, Cell Phone, Brain, Coma, Citrus sinensis, COVID-19, Creatinine, Decision Making, Electrolytes, Diuretics, Heart Atria, Friends, Heart Diseases, Heart Ventricles, Home Nursing, Home Care Services, Heart Failure, Informed Consent, Intensive Care Units, Hospitals, Mitral Valve Insufficiency, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U.S.), Nurses, Community Health, Occupational Therapy, Patient Advocacy, Patient Care, Patient Discharge, Pericarditis, Physical Therapy Modalities, Physicians, Primary Care, Potassium, Pulmonary Artery, Pulmonary Wedge Pressure, Seizures, Registries, Spouses, Stroke Volume, Surgeons, Tomography, X-Ray Computed, Tricuspid Valve Insufficiency, Ventricular Pressure, Vital Signs

< Back to Listings