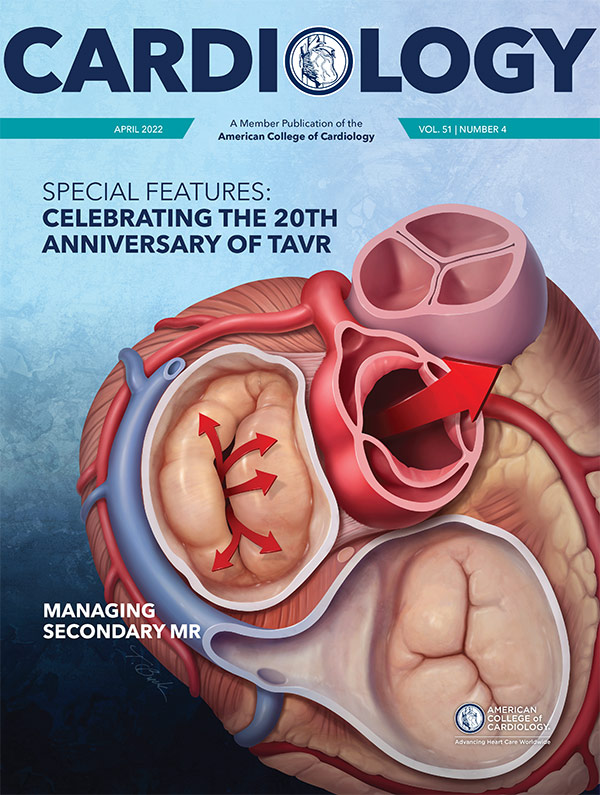

Editor’s Corner | The Path to TAVR: The Backstory

Forty-five years ago, Andreas Gruentzig, MD, performed the first-in-man coronary angioplasty with a primitive balloon catheter he designed in his garage. We all know the rest of this story. But the real story began 19 years earlier in 1958 when F. Mason Sones Jr., MD, was performing an aortic root angiogram to visualize the coronary arteries (selective coronary injection of contrast was thought to cause ventricular fibrillation). Mason's catheter tip slipped into the proximal right coronary and before he could pull it back contrast was injected. No fibrillation – but cardiac standstill – and thus selective coronary angiography was born.

Sones and radiologist Charles Dotter, MD, exemplify the Socratic notion that "Chance favors the prepared mind." The apocryphal story (told to me by Dotter) is that six years later, Dotter was performing a selective coronary angiogram in a patient with unrelenting rest angina using a catheter with a tapered tip. As he engaged the left main coronary and injected contrast, a tight ostial stenosis was revealed and accidentally "stretched" as the slim catheter tip glided past the ostial stenosis into the distal left main. Remarkably, the patient's chest pain disappeared and Dotter went on to develop the "Dotter technique," involving a series of coaxial catheters to treat peripheral atherosclerotic disease.

Dotter was ridiculed in the U.S., but his techniques were adopted by Eberhard Zietler, MD, and others in Europe. Gruentzig translated the bulky tapered catheters into a balloon technique, ventured from peripheral to coronary disease, and here we are. To his credit, Gruentzig repeatedly went out of his way to acknowledge the pioneers who preceded him. "We see far," he said often, "because we stand on the shoulders of giants."

Fast forward to April 2002 and more disruptive technology – the first-in-man transcatheter aortic valve insertion was successfully performed by Alain Cribier, MD, in France. While the patient improved symptomatically, only to succumb to unrelated problems four months later, the proof of concept had been shown. We all know the rest of this story and Cribier has appropriately been feted with numerous awards, accolades and distinguished proclamations, including this year's ACC.22 Presidential Citation.

But, like angioplasty, the story didn't begin there. Interest in ballooning stenotic valves had been conceptualized in the early 1980s by a number of early adopters of transcatheter vascular angioplasty, including Cribier and James E. Lock, MD, who performed the first "official" percutaneous transcatheter mitral commissurotomy, in India in 1985.1

Balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV) was championed by Cribier and others as being a possible alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement.2 Indeed, aortic gradients were commonly decreased by 50% after BAV, making symptoms transiently less severe, but still leaving behind significant stenosis. Initial optimism was replaced by the realization that recurrence was nearly universal. By the late 1980s, it was clear something better was needed.

Henning Rud Andersen, MD, a cardiologist in Denmark, was in Scottsdale, AZ, in 1989 listening to Julio C. Palmaz, MD, talk about animal experiments using a metal stent for coronary insertion when he got the idea for inserting a collapsible biological valve inside a bigger stent. He returned home and within weeks fashioned a wire-stented valve that was successfully implanted in a pig. Further animal studies were done by Andersen; J. Michael Hasenkam, a cardiac surgical trainee; and Lars Knudsen, a medical student. Their three names author the original patent and the results of their studies were ultimately published in the European Heart Journal in 1992. Eight years later, Philipp Bonhoeffer, MD, used the stent-valve concept to implant the first successful percutaneous bovine valve in the right ventricular conduit of a young patient with right ventricular failure after Tetralogy of Fallot repair.4 But for Andersen, in the late 1990s, attempts to find funding for further development were not supported in Denmark. After many failed negotiations, licensing and patent transfers were made to U.S. companies. Technical developments and multiple proof of utility in animals and autopsied human heart experiments by Cribier resulted in his first-in-human success in 2002. The complex patent story has been detailed by Andersen and chronicles the excitement and difficulties that disruptive technology/inventions can offer.3

The story of Heart Teams spawned by TAVI (TAVR) and the collegial cooperation of academic centers, industry and government over the past 20 years that have made TAVI (TAVR) what it is today is beautifully recounted in this feature story. We have indeed come a long way.

Winners write history, but back stories commonly show us how resistant the scientific/medical community can be to new ideas and technology. However, the backstory of TAVI has a lovely twist. Henning Andersen in 2011 implanted a TAVI in his father, who at age 87 was found to have severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis. He went on to live another eight years.

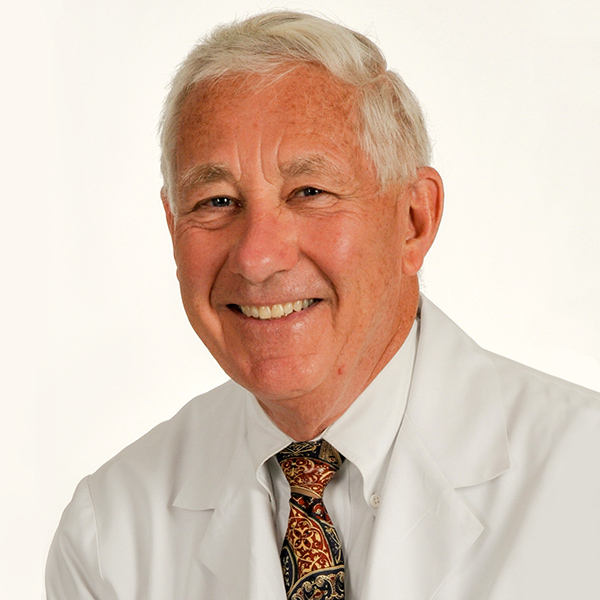

Peter C. Block

Peter C. BlockMD, FACC

References

- Lock JE, Khalilullah M, Shrivastava S, et al. Percutaneous catheter commissurotomy in rheumatic mitral stenosis. N Engl J Med 1985; 313:1515-18.

- Cribier A, Saoudi N, Berland J, et al. Percutaneous transluminal valvuloplasty of acquired aortic stenosis in elderly patients: an alternative to valve replacement? Lancet 1986; 327:63-7.

- Andersen HR. How transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) was born: The struggle for a new invention. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021; 8:72269.

- Bonhoeffer P, Boudjemline Y, Saliba Z, et al. Percutaneous replacement of pulmonary valve in a right-ventricle to pulmonary-artery prosthetic conduit with valve dysfunction. Lancet 2000; 356:1403-5.

Clinical Topics: Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiac Surgery, Cardiovascular Care Team, Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Noninvasive Imaging, Valvular Heart Disease, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Aortic Surgery, Cardiac Surgery and Arrhythmias, Cardiac Surgery and CHD and Pediatrics, Cardiac Surgery and VHD, Congenital Heart Disease, CHD and Pediatrics and Arrhythmias, CHD and Pediatrics and Imaging, CHD and Pediatrics and Interventions, Interventions and Imaging, Interventions and Structural Heart Disease, Angiography, Nuclear Imaging

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement, Aortic Valve, Coronary Angiography, Animal Experimentation, Cardiologists, Constriction, Pathologic, Negotiating, Students, Medical, Tetralogy of Fallot, Ventricular Fibrillation, Aortic Valve Stenosis, Coronary Disease, Radiologists, Angioplasty, Government, Chest Pain, Technology, Catheters, Denmark, Fathers, Awards and Prizes, Europe, France, Stents, India

< Back to Listings