Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Provides Potent Reminder of the Risk of Infectious Agents

The estimates are jarring: up to 440,000 hospitalized and perhaps as many as 36,000 deaths in the U.S. alone.1

The new coronavirus illness dubbed COVID-19?

No, seasonal influenza.

These are the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates of total flu burden in the U.S. for the current season (as of Feb. 22).

While the novel coronavirus (official name, SARS-CoV-2) has been dominating headlines, seasonal influenza is doing its yearly march through the country.

As of Feb. 22, the CDC estimates there have already been 32 million individuals infected with seasonal flu, 310,000 hospitalizations, and 18,000 deaths, 125 of them in children.

Thankfully, flu activity in the U.S. has been slowing for the last few weeks and overall severity is considered moderate this year, albeit with high rates among children and young adults.

The specific effects of COVID-19 on the cardiovascular system remain unclear, though there have been reports of acute cardiac injury, arrhythmias, hypotension, tachycardia, and a high proportion of concomitant cardiovascular disease in infected individuals, particularly those who require more intensive care.

"We're all flying blind regarding coronavirus, but it's fair to think that many of the issues that surround influenza and the cardiovascular system will be at play, including the obvious fact that many of our patients who are at high risk will be particularly vulnerable to complications," says Scott D. Solomon, MD, FACC, from Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston.

What all the experts who Cardiology spoke with agree on is this: COVID-19 provides a potent reminder of the seasonal threat that is influenza infection on patients with cardiovascular disease.

"For COVID-19, we'll apply what we've learned from influenza – the focus will be on vaccination and prevention through frequent handwashing, breaking the chain of transmission; securing the safety of health care personnel; and trying to lower cardiovascular risk in our patients with underlying chronic conditions," says Mohammad Madjid, MD, FACC, from UTHealth in Houston.

The Flu and Cardiovascular Events

There is consensus among experts that both coronary artery disease and heart failure (HF) patients are at increased risk of acute events or exacerbations from viral respiratory infections, with other comorbidities (diabetes, obesity, hypertension, COPD, kidney disease) further increasing risk.

Acute viral infections have three categories of short-term effects on the cardiovascular system:

- First, increased risk of acute coronary syndromes associated with the severe inflammatory response to the infection.

- Second, myocardial depression leading to heart failure.

- Third, under-recognized risk of arrhythmias, also related to acute inflammation.

"It's really just a very toxic environment as far as the heart is concerned," says Madjid, who has been studying the impact of influenza on heart patients for more than 20 years.

"Along with these other things, almost all of these patients get pneumonia, and many also get renal failure or bacteremia. And, unfortunately many critical patients develop acute respiratory distress syndrome…all of which are deleterious to the cardiovascular system," he adds.

It's been suggested that influenza may precipitate plaque rupture, increase cytokines that destabilize plaques and trigger the coagulation cascade, but clear causal mechanisms by which the flu precipitates adverse events are unclear.

"Our animal studies in apo-E knockout hypercholesterolemic mice showed that influenza virus directly infects the atherosclerotic plaques and causes severe cellular inflammation at vascular levels," says Madjid in an interview.

"There is also solid evidence that influenza infection can increase the risk of acute coronary syndromes and several trials have shown that influenza vaccination can prevent myocardial infarctions (MI). However, our studies have shown that only two-thirds of patients with cardiac disease receive the vaccine and the primary reason for failing to receive it is the patients' lack of awareness about their need for the vaccine."

The ACC/American Heart Association (AHA) secondary prevention guidelines recommend influenza vaccination as a measure to reduce risk of cardiovascular events.

Influenza is not only a dangerous complication in patients with HF, but also likely an important precipitant of HF. In a recent ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) report that measured across four influenza seasons, a 5% monthly absolute increase in influenza activity was associated with a 24% increase in HF hospitalization.2

Influenza activity was not significantly associated with MI-related hospitalization in this study, but has been in other studies where the clear temporal relationship between influenza infection and MI could be assessed.

Once HF patients are hospitalized, concomitant influenza infection increases risk. In a study that utilized data from the National Inpatient Sample, HF hospitalization with concomitant influenza infection increased the incidence of in-hospital mortality (6.2% vs. 5.4%; odds ratio, 1.15; p=0.02), acute respiratory failure (36.9% vs. 23.1%; OR, 1.95; p<0.001), acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation (18.2% vs. 11.3%; OR, 1.75; p<0.001), acute kidney injury (30.3% vs. 28.7%; OR, 1.08; p=0.01), and kidney injury requiring dialysis (2.4% vs. 1.8%; OR, 1.37; p=0.001).3 Mean length of stay was longer for patients with flu (5.9 vs. 5.2 days; p<0.001).

It would make sense that vaccinating high-risk individuals against influenza would lower the risks associated with infection, but there are actually few controlled trials supporting this.4,5

That said, "we have pretty solid evidence from observational studies and other sources that vaccination does indeed reduce the risk of adverse events," says Orly Vardeny, PharmD, from the University of Minnesota.

COVID-19: A Once-in-a-Century Pandemic?

When this article was in the planning phase in early February, the novel coronavirus from Wuhan was going to be the "hook" to discuss the larger issue of seasonal influenza. As we go to press in early March, coronavirus is rapidly spreading across the globe and will likely soon be officially labelled a pandemic. The hook has become the story.

As of Feb. 29, COVID-19 had infected 85,403 people (79,394 in China) and caused 2,867 confirmed deaths across 61 countries (2,838 deaths in China alone).

"It's still too early to fully characterize and quantify the cardiovascular impact of COVID-19, but we know coronaviruses have the potential to trigger myocardial infarctions, as seen with SARS and MERS, and multiple viruses have been linked to acute MI and rapid-onset heart failure," says Mohammad Madjid, MD, FACC, from UTHealth in Houston.

"Since both influenza and coronavirus are circulating currently, distinguishing between them early could become important for these patients who are more prone to complications since there is a treatment for influenza (Tamiflu) but not for coronavirus as of yet," according to Orly Vardeny, PharmD, from the University of Minnesota.

"Considerations for patients with underlying cardiovascular disease are, thus far, similar with what we know from prior influenza seasons. Older adults may have different presenting symptoms compared with younger individuals – less fever – so attention to other symptoms like cough or shortness of breath is prudent," she adds.

COVID-19 appears to have greater infectivity as compared with influenza, although these estimates are still evolving. Case mortality with COVID-19 is currently thought to be around 3.4%, higher in hypertensives, diabetics, patients with underlying cardiovascular disease, and the elderly. This is much higher than the 0.1% mortality with seasonal influenza, but is also likely a high estimate, as most studies to date have included more severe cases of the disease.

"The actual mortality rate may not be much higher (or higher) than flu where there is much better surveillance data available," says Scott Solomon, MD, FACC, from Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, one of the authors of ACC's Clinical Bulletin.

In the U.S., there are eight states with confirmed and presumptive positive cases of COVID-19; 15 confirmed and seven presumptive cases and one death (in a presumptive case).1 These numbers are expected to rise as more sites ramp up to test for the virus.

The latest data from China offers some basic stats on the virus: the median age of 1,099 patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 from 552 hospitals in 30 provinces in China was 47 years, and 41.9% are female.2 Intensive care unit admission was seen in 5.0%, mechanical ventilation used in 2.3%, and 1.4% died. The most common symptoms were fever and cough, diarrhea was uncommon, and median incubation period was 4 days.

So far, COVID-19 appears to have greater infectivity and a lower-case fatality rate as compared with SARS and MERs.

It's not every day that Bill Gates publishes an article in the New England Journal of Medicine, so seeing his debut article online on Feb. 28 likely came as a surprise to many.3 But his Foundation has committed substantial resources in recent years to global preparations for a "once-in-a-century pathogen," so he knows something about this.

In short, his article called on government and industry to work together to contain the COVID-19 coronavirus post haste and without the usual anxieties over borders and market share.

References

- CDC. International Locations with Confirmed COVID-19 Cases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published Feb. 11, 2020. Accessed here, March 1, 2020.

- Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020;Feb 28:[Epub ahead of print].

- Gates B. Responding to Covid-19 - A Once-in-a-Century Pandemic? N Engl J Med 2020;Feb 28:[Epub ahead of print].

"In this country, vaccination is the standard of care, so a randomized clinical trial here would not be considered ethical," she notes.

Vardeny has been studying the link between influenza and heart disease for well over a decade. She is a co-author on a recent nationwide cohort from Denmark which showed that annual vaccination in patients with HF was associated with an 18% reduced risk of all-cause death and an 18% reduced risk of cardiovascular death after adjustment for multiple confounders (both p<0.001).6

Getting vaccinated early in the season and receiving more cumulative yearly vaccinations were associated with larger reductions in risk compared to late-season or intermittent vaccination.

Interestingly, those who received more than one seasonal vaccination also had a greater reduction in risk of incident atrial fibrillation (HR, 0.94; p=0.009).

"The atrial fibrillation finding was interesting because some studies have shown benefit with vaccination in terms of arrhythmias and others haven't," says Vardeny. Interestingly, one study showed that in patients with implantable devices, more shocks were delivered during flu season than during other times of the year," so there seems to be a correlation between higher arrhythmia burden and flu season," she adds.

One of the strongest pieces of evidence supporting vaccination comes from observational data derived from the PARADIGM-HF trial, in which only 21% of 8,399 participants with symptomatic HF with reduced ejection fraction received vaccination within a 12-month period while enrolled in the study.7

Vaccination was associated with a 19% decrease in the relative risk of death, although this figure is subject to confounding from the inherent patients' risk and selection biases, as well as regional differences in quality of care that patients received.8

"I think this study importantly highlights that there are still many high-risk patients not getting vaccinated," says Vardeny.

There are currently two randomized trials ongoing testing influenza vaccination against placebo in patients with cardiovascular disease – both are being conducted in countries where mass vaccination is not the standard of care.4,9

Results from the second trial, called the Influenza Vaccination After Myocardial Infarction (IAMI) trial, are expected in September of this year.9 That trial has randomly assigned 4400 patients with STEMI, NSTEMI or very high risk stable coronary artery disease to vaccination or placebo.

Get With the Flu Jab

"There is still a problem with people who are high risk not receiving vaccines. Part of it is, as health care providers, we need to provide opportunity for influenza vaccination whenever possible," says Vardeny.

"So, if patients are coming to see the cardiologist more frequently than their primary care provider, then the cardiologist could give the vaccination, or at least have a very deliberate discussion on how important it is for the patients to be vaccinated," adds Vardeny.

The CDC, Health Canada, and several European countries have taken a transmission-based, universal vaccination approach to limit disease burden, recommending yearly vaccination for everyone six months and older.

Some European countries, however, still follow a more risk-based approach, prioritizing vaccination for at-risk groups who are most likely to suffer a severer outcome from influenza infection – the elderly, children, pregnant women, those with underlying health conditions.5

Vaccination rates in patients with HF are suboptimal. In a Get with the Guidelines Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) registry analysis, about one-third of patients hospitalized with HF were not vaccinated for influenza or pneumococcal pneumonia, with no improvement from 2012 to 2017.10

Hospitals with higher vaccination rates were more likely to score higher on adherence to GWTG-HF performance measure, but no difference was seen in one-year all-cause mortality for influenza vaccination.

At Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals, patients are immediately flagged and jabbed if they come in not having had a flu vaccination. "During flu season, it's all hands on deck at the VA. There are signs everywhere asking if you've had your flu shot and if you haven't, the vaccine is offered and provided before or after your appointment," says Vardeny.

Interestingly, it's likely that standard flu shots don't work as well in HF patients as they do in others. In work done by Vardeny a decade ago, HF patients did not mount as vigorous an antibody immune response to influenza vaccination and had a more pronounced waning of antibody titer levels compared with matched individuals without the disease.11,12

The INVESTED trial is the largest and longest study to assess whether high-dose influenza vaccine is superior to standard-dose vaccines for reducing cardiopulmonary events in high risk patients.13 The trial is ongoing and enrolled individuals within 12 months of acute MI or within 24 months of a HF hospitalization. Findings will be presented at a cardiology meeting in 2020.

"Our primary outcome is a composite of all-cause mortality or cardiopulmonary hospitalizations," says Vardeny, who is a co-principal investigator of the trial with Solomon.

"We are also checking antibody titers to influenza antigens in a subset of participants and will examine whether antibody response is associated with the primary composite outcome. We hypothesize that, given a correlation between flu and acute cardiac events, the potential benefit of high-dose vaccination comes through reduction in flu and therefore reduction in cardiac risk," she says.

Even in older individuals without HF, higher-dose vaccination may be better. A 2014 study found that among those 65 years and older, a high-dose vaccine induced significantly higher antibody responses and provided better protection against flu than did a standard-dose product.14

Currently there is a U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved high-dose vaccine that offers quadruple the amount of antigen. It's indicated for individuals 65 years and older, but Vardeny says it's not the standard of care in the U.S. and costs twice as much as the standard-dose flu shot, so it is likely many older patients are not receiving it.

174 Million Doses and Counting

Every year the CDC uses a combination of hospitalization surveillance reports (adjusted for behavior factors since not everyone goes to the hospital when they feel awful), and death reports to create mathematical models to estimate the influenza burden in the U.S. They also estimate vaccine effectiveness, track immunization rates, and provide myriad other details on seasonal influenza.

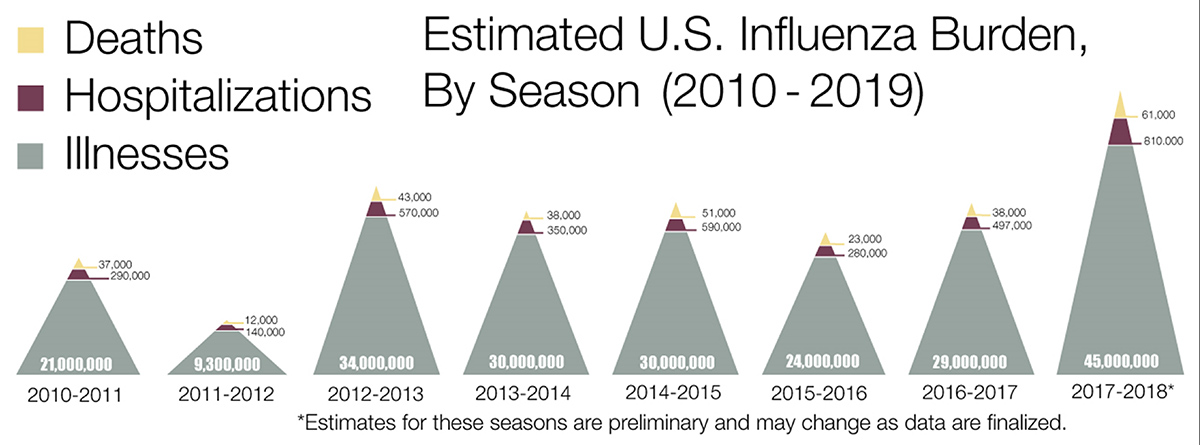

This year's flu season – with 16,000 deaths as of Feb. 20 – appears to be of "average" severity, if not slightly less severe than some recent years and clearly less severe than the 2017-2018 season, which caused 61,000 deaths in the U.S.15 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Estimated Influenza Disease Burden in the U.S. 2010-11 Through 2017-18 Influenza Seasons

Figure 1 Estimated Influenza Disease Burden in the U.S. 2010-11 Through 2017-18 Influenza SeasonsAccessed here, Feb. 20, 2020

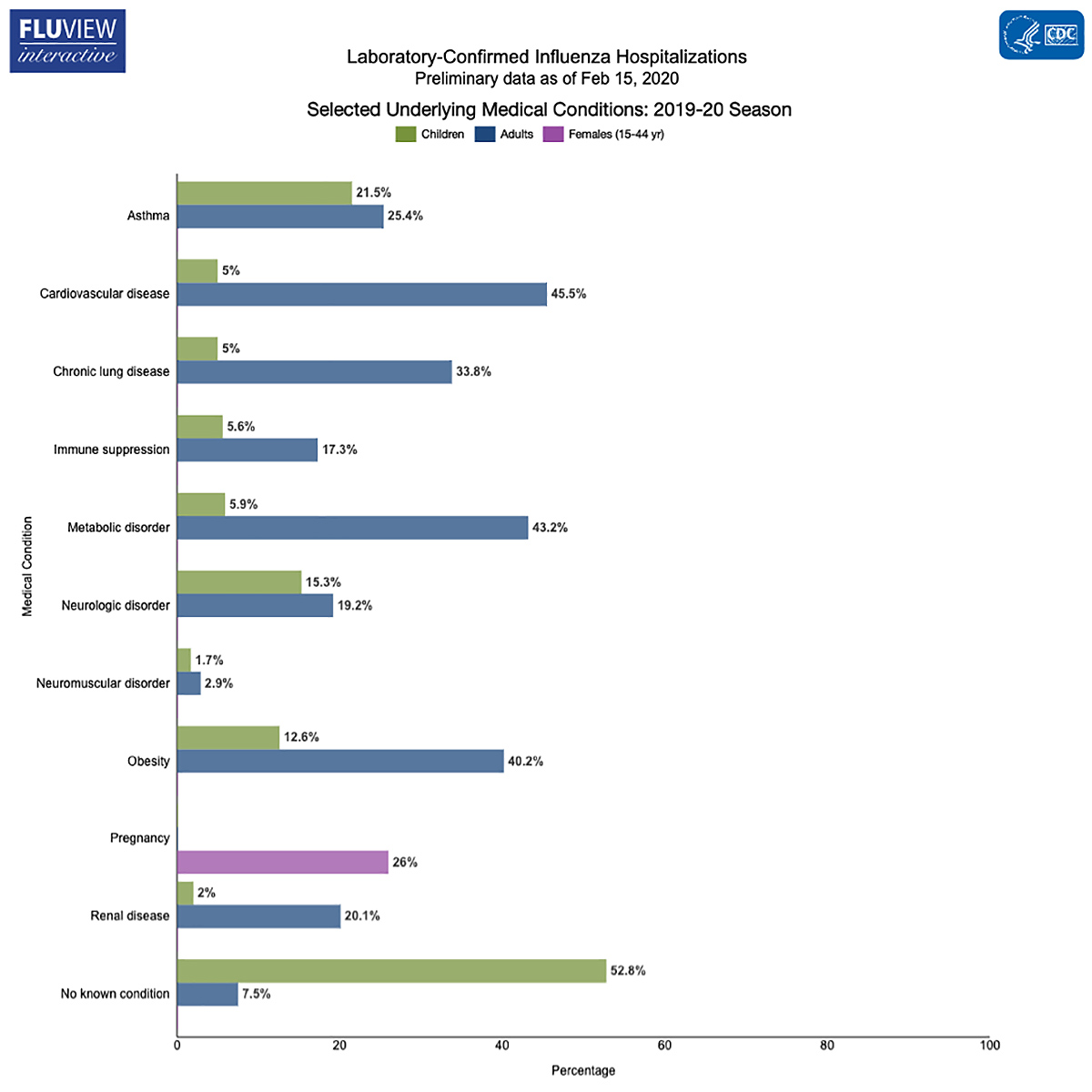

Also about par for the course is the large proportion of laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations seen in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease. Nearly half (45.5%) of adults hospitalized with flu are at high risk because of comorbid cardiovascular disease (defined as including coronary heart disease, valve disorders, congestive heart failure, and pulmonary hypertension, but excluding isolated hypertension) (Figure 2).

If the goal is to get as many people vaccinated against flu as possible, based on CDC figures, it seems we are doing well: as of Feb. 15, 174.1 million doses of flu vaccine have been distributed this season. This handily beats the 155.5 million people dosed in 2017-2018.

Vaccination rates don't appear to be noticeably up in response to COVID-19; the vast majority of recipients were vaccinated before the new coronavirus hit the news.

The overall estimated effectiveness of the 2019-2020 seasonal influenza vaccine for preventing medically attended, laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infection is 45%, jumping to 55% in younger folks (aged six months to 17 years).16 Vaccine effectiveness typically fluctuates between 40% and 60%.

Even given suboptimal effectiveness, there is no question that influenza vaccination substantially reduces the burden of influenza-associated illness.

In the 2017-2018 season – the season with the highest morbidity and mortality since the 2009 pandemic - a CDC study found that despite vaccine effectiveness of only 38% (varying from 22% to 66% depending on the strain), the flu shot prevented an estimated 7.1 million illnesses, 3.7 million medical visits, 109,000 hospitalizations and 8,000 deaths.17 An estimated 42% of the U.S. population was vaccinated against flu that year.18,19

With COVID-19 at the gates and knocking, vaccination is more important than ever, says Madjid. "Young people might think they don't need to bother with a flu shot because they're young and healthy, but what happens when you get flu and give it to the elderly person, your grandparents maybe, who aren't young and healthy and might have heart disease?"

"Also, just practically speaking, if this coronavirus is coming, this is not a good year to risk being hospitalized for flu, if only because it will present a diagnostic challenge to determine whether you have flu or COVID-19," he says.

References

- 2019-2020 U.S. Flu Season: Preliminary Burden Estimates | CDC. Accessed here, Feb. 20, 2020.

- Kytömaa S, Hegde S, Claggett B, et al. Association of influenza-like illness activity with hospitalizations for heart failure: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:363-9.

- Panhwar MS, Kalra A, Gupta T, et al. Effect of influenza on outcomes in patients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2019;7:112-7.

- Loeb M, Dokainish H, Dans A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of influenza vaccine in patients with heart failure to reduce adverse vascular events (IVVE): Rationale and design. Am Heart J 2019;212:36-44.

- Sullivan SG, Price OH, Regan AK. Burden, effectiveness and safety of influenza vaccines in elderly, paediatric and pregnant populations. Ther Adv Vaccines Immunother 2019;7.

- Modin D, Jørgensen ME, Gislason G, et al. Influenza vaccine in heart failure. Circulation 2019;139:575-86.

- Vardeny O, Claggett B, Udell JA, et al. Influenza vaccination in patients with chronic heart failure: The PARADIGM-HF trial. JACC Heart Fail 2016;4:152-8.

- Beck da Silva L, Rohde LE. Vaccinations in heart failure: an expert-opinion based recommendation that deserves randomized validation. JACC Heart Fail 2018;6:856-58.

- Fröbert O, Götberg M, Angerås O, et al. Design and rationale for the Influenza vaccination After Myocardial Infarction (IAMI) trial. A registry-based randomized clinical trial. Am Heart J 2017;189:94-102.

- Bhatt AS, Liang L, DeVore AD, et al. Vaccination Trends in patients with heart failure: insights from Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail 2018;6:844-855.

- Vardeny O, Sweitzer NK, Detry MA, et al. Decreased immune responses to influenza vaccination in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail 2009;15:368-73.

- Van Ermen A, Hermanson MP, Moran JM, Sweitzer NK, Johnson MR, Vardeny O. Double dose vs. standard dose influenza vaccination in patients with heart failure: a pilot study. Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:560-4.

- Vardeny O, Udell JA, Joseph J, et al. High-dose influenza vaccine to reduce clinical outcomes in high-risk cardiovascular patients: Rationale and design of the INVESTED trial. Am Heart J 2018;202:97-103.

- Diaz Granados CA, Dunning AJ, Kimmel M, et al. Efficacy of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med 2014;371:635-45.

- Estimated Influenza Illnesses, Medical visits, hospitalizations, and deaths in the United States - 2017–2018 influenza season | CDC. Published Nov 2019. Accessed here, Feb. 20, 2020.

- Dawood FS. Interim Estimates of 2019–20 Seasonal s Vaccine Effectiveness - United States, February 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69.

- Rolfes MA, Flannery B, Chung JR, et al. Effects of influenza vaccination in the United States during the 2017–2018 influenza season. Clin Infect Dis 2019;69:1845-53.

- Estimates of Influenza Vaccination Coverage among Adults - United States, 2017–18 Flu Season | FluVaxView | Seasonal Influenza (Flu) | CDC. Published April 3, 2019. Accessed here, Feb. 20, 2020.

- Estimates of Flu Vaccination Coverage among Children - United States, 2017–18 Flu Season | FluVaxView | Seasonal Influenza (Flu) | CDC. Published Feb. 26, 2019. Accessed here, Feb. 20, 2020.

Clinical Topics: Acute Coronary Syndromes, Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardiovascular Care Team, Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies, Prevention, Atherosclerotic Disease (CAD/PAD), Implantable Devices, SCD/Ventricular Arrhythmias, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias, Acute Heart Failure, Hypertension

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, Influenza, Human, Coronary Artery Disease, Cardiovascular Diseases, Coronavirus, Plaque, Atherosclerotic, Acute Coronary Syndrome, SARS Virus, Hand Disinfection, Hand Disinfection, Consensus, Risk Factors, Influenza Vaccines, Vaccination, Myocardial Infarction, Orthomyxoviridae, Arrhythmias, Cardiac, Heart Failure, Pneumonia, Renal Insufficiency, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S., Tachycardia, Hypotension, Critical Care, Hypertension, Diabetes Mellitus, Obesity, Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive

< Back to Listings