Feature | Challenges For the Cardiovascular Community During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Infection with the acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has now spread worldwide1 and has become a challenge for health care systems.2 More than 1 million people in the U.S. are infected with SARS-CoV-2, as we write this article, with fatalities in the range of 60,000.3

Although, mortality may be lower than initially feared, likely well below 1%,4 the mortality figures overall are still staggering. Economically, this pandemic has left more than 26 million people without a job in the U.S. alone.5

Health care systems worldwide have had to rearrange staff and wards to accommodate patients with suspected COVID infection, making "COVID units" standard. Challenges presented by this global pandemic are both acute and long-lasting.

Some of these challenges are particular to cardiovascular specialists.

The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) has different presentations and outcomes. Although, the large majority of patients with COVID-19 have mild disease,6 some patients will develop severe illness including multiorgan system failure and death.7

There is, however, an increased amount of data suggesting a large number of asymptomatic carriers8 and asymptomatic transmission,9 which complicates logistics for screening and containment.

Future patterns of COVID-19 infections are unknown, with secondary outbreaks possible once states reopen. Initially, there was hope for antiviral treatments such as lopinavir-ritonavir and hydroxychloroquine due to demonstrable in vitro activity against SARS-CoV-2.10

However, isolated reports have decreased enthusiasm.11,12 Remdisivir has shown some promise in shortening time to recovery,13 despite some evidence of lack of effect on outcomes;14 clinical availability is still in question. Thus, for now, we remain with supportive care as the mainstay of treatment.

It is clear that in the absence of an effective (and available) treatment or vaccine, it is plausible that multiple outbreaks and "waves" could be problematic in the months to come.

It is essential that health care systems and physicians prepare for the potential for intermittent lockdowns and likely "seasonality" of this disease.

The use of personal protection equipment (PPE) in the hospital is likely to become the new standard of care. Under experimental circumstances aerosol and fomite transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is plausible, because the virus can remain viable and infectious in aerosols for hours and on surfaces up to days.15

This forces physicians to carefully select patients for high-risk procedures, such as those that are aerosol-generating (transesophageal echocardiography [TEE] among them).

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recommended the cessation of all elective procedures. Consequently, multiple state governors issued executive orders to halt all elective surgeries.

Therefore, when planning the reopening of more elective cardiac procedures and outpatient testing at hospitals, health systems will need to weigh the impact on their stock of PPE.

The need for PPE will only continue to grow, because procedures such as TEE, intubations and bronchoscopies will remain high risk until there is an effective treatment or effective vaccine.

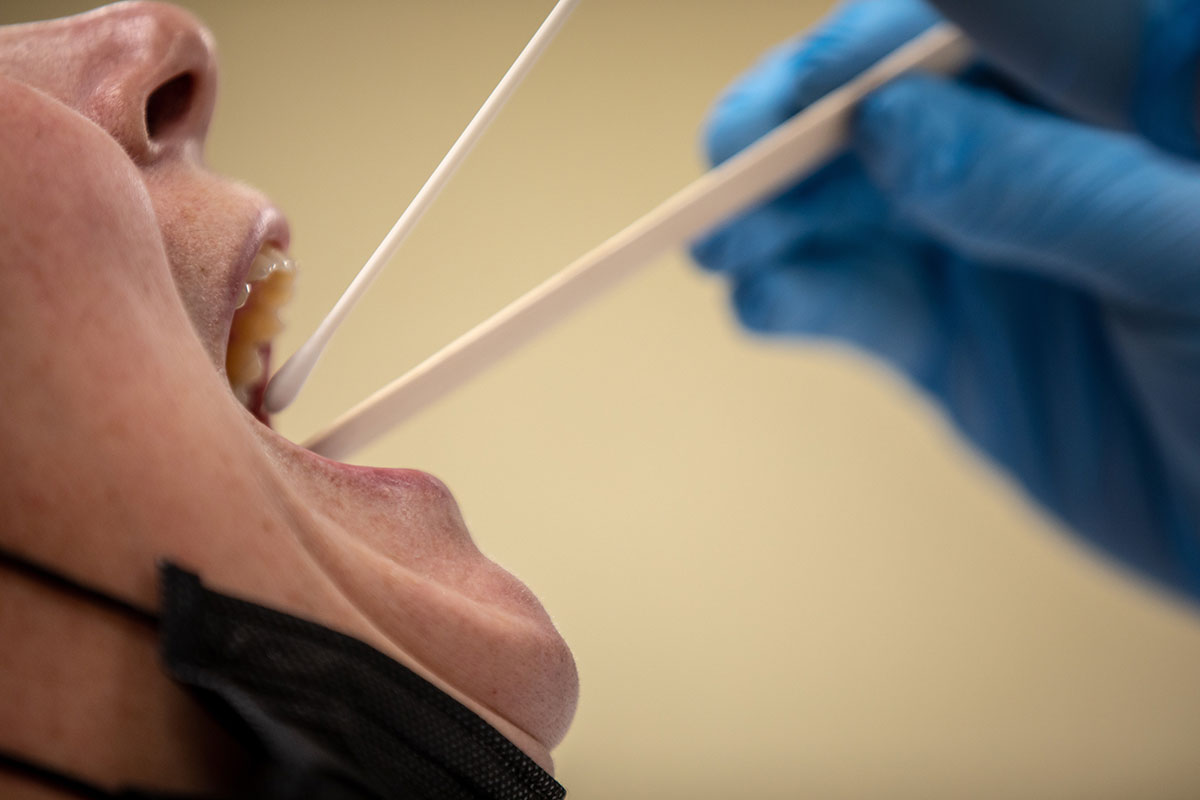

Testing has proven to be a challenge. Some have considered requiring a negative COVID-19 test for all elective procedures.

In a study of 205 patients with COVID-19, bronchioalveolar lavage specimens showed the highest positive rates (93%), followed by sputum (72%), nasal swabs (63%), fibrobronchoscope brush biopsy (46%), pharyngeal swabs (32%), feces (29%) and blood (1%).16

Therefore, despite a negative test, health care workers may still be at risk.

Nonetheless, testing patients presenting to the hospital for elective tests or procedures could reduce exposure risk and allow a smoother transition to delivering elective care.

Regarding the testing of providers, the utility of antibody testing is presently unclear, with further data needed. Allowing individuals to reenter society based on antibody status assumes that past infection guards against reinfection, something that is not well defined yet.17

It is likely that when/if a reliable vaccine becomes available, testing will become an occupational requirement for health care workers.

Unfortunately, research and manufacturing of such a vaccine makes availability impossible prior to opening of economies and increasing outpatient elective procedure volume.

Many are concerned that the impending influenza season could compound recovery from the COVID pandemic. Throughout the upcoming influenza season, any patient presenting with an influenza-like illness will remain a COVID-19 suspect.

Therefore, the fears of system collapse may be worse in the fall and winter. COVID units are likely not going to disappear and health care workers and systems will need to continue to adapt.

The emotional toll on communities, in the near future at least, is uncertain, but likely significant. Patient needs for care will continue, and are likely to increase.

The impact on the younger generation is unknown. Moreover, the psychological impact of quarantine, online learning and widespread social media misinformation in children and adolescents remains to be seen.

The emotional sequelae of the pandemic on the medical staff must be mitigated, particularly among front line workers. There are both moral and economic reasons the psychological impacts of the pandemic cannot be ignored.

Early action, such as creating task forces or groups to identify and attend to the emotional well-being of all staff seems a logical step.

At the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City, one such group has identified three priority areas central to promotion and maintaining well-being of staff:

- Meeting basic daily needs

- Enhancing communications for delivering current, reliable and reassuring messages

- Developing robust psychosocial and mental health support options18

Finally, the potential long-term cardiac sequelae of COVID-19 is not presently established.

Globally, as we see fewer admissions for acute cardiac issues during the pandemic,19 only time will tell whether there will or will not be a surge in cases in the short -term. If so, this will pose a further unique and unprecedented strain on the medical system, and by itself will carry its own public health implications.

Delays in care for acute coronary syndrome, heart attacks, stroke and heart failure may leave individuals and communities with adverse long-term health issues.20,21

While apparently not the primary target of the virus, it is clear that cardiovascular involvement can be serious.22 The long-term consequences of this are yet unknown.

At this time, we are unable to accurately predict all of the ramifications of the global COVID-19 crisis.

Yet, several things remain clear:

- It is our obligation to continue to carefully and methodically deliver care for all cardiac patients. Cardiovascular disease remains the number one cause of mortality; excess distraction by the sweeping infective crisis could jeopardize the health of society.

- Vigilance is essential regarding the evolving science in relation to COVID-19 for evolution of care.

- Engagement of physicians with scientists, policy makers and health care systems is needed to help guide care through these turbulent times – while maintaining patient-centered care.

All of this is our opportunity and our obligation.

References

- Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed 2020;91:157-60.

- Fauci AS, Lane HC, Redfield RR. Covid-19 - Navigating the Uncharted. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1268-9.

- Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, coronavirus.jhu.edu.

- Wilson N, Kvalsvig A, Barnard LT, Baker MG. Case-fatality risk estimates for COVID-19 calculated by using a lag time for fatality. Emerg Infect Dis 2020;26.

- US weekly jobless claims hit 4.4 million, bringing 5-week total to more than 26 million. Available here.

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72314 cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020;323;1239-42.

- Weiss P, Murdoch DR. Clinical course and mortality risk of severe COVID-19. Lancet 2020;395:1014-5.

- Sutton D, Fuchs K, D'Alton M, Goffman D. Universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 in women admitted for delivery. N Engl J Med 2020;April 13:[Epub ahead of print].

- Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA 2020;323:1406-7.

- Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res 2020;30:269-71.

- Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020;10.1056/NEJMoa2001282.

- American College of Cardiology News Story. FDA drug safety announcement cautions against the use of hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine in COVID-19. Available here. Accessed April 28, 2020.

- National Institutes of Health News Release. NIH clinical trial shows remdesivir accelerates recovery from advanced COVID-19. Available here. Accessed May 1, 2020.

- Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19; a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled multicentre trial. Lancet 2020;10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9.

- van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1564-7.

- Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA 2020;March 11:[Epub ahead of print].

- Abbasi J. The Promise and Peril of Antibody Testing for COVID-19. JAMA 2020;Apr 17[Eoub ahead of print].

- Ripp J, Peccoralo L, Charney D. Attending to the Emotional well-being of the health care workforce in a New York City health system during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Med 2020;April 10:[Epub ahead of print].

- Garcia S, Albaghdadi MS, Meraj PM, et al. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;April 9:[Epub ahead of print].

- De Filippo O, D'Ascenzo F, Angelini F, et al. Reduced rate of hospital admissions for ACS during Covid-19 outbreak in Northern Italy. N Engl J Med 2020;April 28;{Epub ahead of print].

- Kolata, G. Amid the Coronavirus crisis, heart and stroke patients go missing. Available here. Accessed April 26, 2020.

- Hendren N, Drazner M, Bozkurt B, Cooper L. Description and proposed management of the acute COVID-19 cardiovascular syndrome. Circulation 2020; April 16:[Epub ahead of print].

Clinical Topics: COVID-19 Hub, Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention, Noninvasive Imaging, Stable Ischemic Heart Disease, Vascular Medicine, Interventions and Imaging, Interventions and Vascular Medicine, Angiography, Nuclear Imaging, Chronic Angina

Keywords: ACC Publications, Cardiology Magazine, COVID-19, Pandemics, Coronavirus, Coronavirus Infections, SARS Virus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Quarantine, Fellowships and Scholarships, Coronary Angiography, Hospitals, General, Personal Protective Equipment, ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction, Universities, Problem-Based Learning, Education, Distance, Inpatients, Uncertainty

< Back to Listings